Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

Chapter 135: “Popular Sovereignty” Becomes The Democrat’s Answer To The Wilmot Proviso

Winter 1847-48

The Democrats Search For A “Solution” To The Wilmot Proviso

While the Whigs continue to hammer away at Polk over his motives for the war, the Democrats are desperately searching for a path to securing peace within their own party.

They must arrive at an option to Wilmot’s total ban on the expansion of slavery into the west, which is anathema to their entire Southern wing.

The house has repeatedly rejected their first choice – declaring that the 34’30” Missouri Compromise line be the boundary for Slave vs. Free State designation in all newly acquired land.

As a fallback, they turn to a new option, one will become known as “popular sovereignty.”

On the surface the idea is simple and consistent with the original spirit of personal liberty in America – namely, that the people themselves should determine the rules by which they will be governed.

John Calhoun’s February 15, 1847 address in opposition to the Wilmot Proviso cites this theme in his “fourth resolve:”

Resolved, That it is a fundamental principle in our political creed, that a people, in forming a constitution, have the unconditional right to form and adopt the government which they may think best calculated to secure their liberty, prosperity, and happiness; and that, in conformity thereto, no other condition is imposed by the Federal Constitution on a State, in order to be admitted into this Union, except that its constitution shall be republican; and that the imposition of any other by Congress would not only be in violation of the constitution, but in direct conflict with the principle on which our political system rests.”

This classical argument of the States’ Rights Democrats goes back to Jefferson, and is disputed by the Federalist conviction that local “sovereignty” is trumped by the majority will of the nation as a whole. Sixty years after the 1787 “constitutional contract” this fundamental dispute still simmers – and, as always, within the context of Southern demands related to slavery and its economic imperatives.

On December 22, 1847, the “popular sovereignty” solution is floated out on the floor of the Senate by Senator Daniel Dickinson of New York. He is a member of the “Hunker” faction in the state, men who seek to smooth tensions with the South, and who oppose the “Barnburner” wing’s attempt to stop the spread of slavery.

The Enduring Rift Within The New York Democrats

| Factions | Key Members |

| “Barnburners” (Pro Wilmot) | Martin Van Buren, John Van Buren, Preston King, Silas Wright, John Dix |

| “Hunkers” (Anti-Wilmot) | Daniel Dickinson, William Marcy, Horatio Seymour, Edwin Crosswell, Samuel Beardsley |

Given New York State’s 36 Electoral College votes, it is regarded as crucial to victory in the 1848 political race. And while Polk was able to carry it for theDemocrates in 1844, the Whig Harrison won there in 1840. So it is considered “in play” as 1848 approaches.

Top Ten Electoral Vote States In 1848

| N.Y. | Pa | Ohio | Va | Tenn | Mass | Ky | Ind | NC | Ga | All Other | Total US |

| 36 | 26 | 23 | 17 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 172 | 290 |

It will now be up to two powerful Western Democrats – Lewis Cass of Michigan and Stephen Douglas of Illinois – to make the case for “popular sovereignty” as the road to alignment and victory in 1848.

With Polk holding true to his promise of one term in office, both men also have their eyes on the nomination.

Winter 1847-48

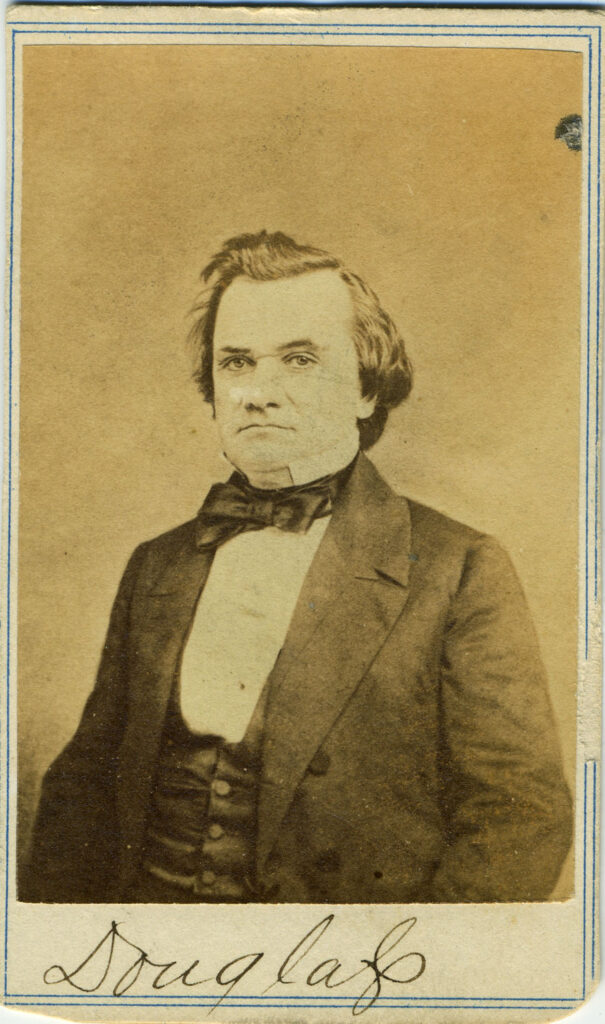

Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas Promotes “Popular Sovereignty

It is the 35 year old Douglas who becomes the most visible spokesperson for “pop sov” from the beginning.

From early on, two raw ambitions drive “the Little Giant” power and wealth.

Power has come to him through a meteoric political career, organizing the Democratic Party machine in Illinois, then heading to the U.S. House in 1843 and the Senate in 1847.

His idol all along has been Andrew Jackson, and like the ex-President, he is an outright racist, as his harsh rhetoric demonstrates. In March 1847, he also becomes a slave-owner through his marriage to Martha Martin, who inherits a large cotton plantation in Mississippi.

This property will provide Douglas with wealth and spare capital, which he uses throughout his career to buy up land around Chicago, always with an eye to windfall profits if he can someday route a trans-continental railroad through the city.

To protect his political image in the North, Douglas manages his Mississippi plantation surreptitiously.

Both his views on blacks and his personal stake in the future of cotton and slaves make him an ideal ally for his Southern colleagues in the capital. In fact, while in DC, he shares his living quarters with four leading Southerners, and their slave servants, in what becomes known as the “F-Street mess.” Three of his housemates chair important Senate Committees — Finance (Robert TM Hunter of Virginia), Foreign Affairs (James Mason of Virginia), and Judiciary (Andrew Butler of South Carolina). The fourth is the outspoken pro-slavery Missouri Senator, David Atchison.

Douglas himself is Chairman of the Committee on Territories, a perfect position from which to both shape and promote “popular sovereignty” in the new western lands. He describes the process to statehood as follows:

- Once a sizable number settle in a new Territory, they will hold a State convention.

- At this convention, they will write and debate a State Constitution.

- Included in this document will be a “free state” or “slave state” declaration.

- The Constitution will then be voted on – yes or no – by all citizens of the State.

- Once a Constitution has passed, the Territory will apply to Washington for recognition.

Both Cass and Douglas believe that “popular sovereignty” will thread the political needle between Northerners, uncertain about extending slavery into the west, and Southerners, demanding it. But first, they must “sell” the idea.

February 14-15, 1848

The Southern “Fire-Eaters” Propose Their “Alabama Platform”

Their first attempt comes up against a growing band of Southern Democrats soon to be known as the “Fire-eaters.”

This faction understands that the entire economic future of the South rests on raising cotton and selling slaves west of the Mississippi, from Texas to California – and they want “guarantees” of this outcome from Washington.

“Popular sovereignty” boosts their odds of success above Wilmot’s flat-out ban; but it falls well short of the “certainties” they point to in the U.S. Constitution and even the 1820 Missouri Compromise. Simply put, the risks of a pop-sov vote going against them are too high to bear.

One “Fire-Eater” who now joins Calhoun in attempting to unite the South behind a better option is Senator William L. Yancey of Alabama.

Yancey is born in Georgia and educated at Williams College in Massachusetts. His step-father is a New School Presbyterian minister who supports abolition, and other family members are strongly pro-Union.

After college he moves to South Carolina, edits a local newspaper, and speaks out against the 1832 “Nullification Bill” proposed by John Calhoun. In 1834 he passes the bar and begins to practice law.

At this point he looks like anything but a future pro-slavery secessionist.

In 1838 his views shift when he marries the daughter of a wealthy Alabama planter and receives, as a dowry-extensive cotton producing land near the town of Cahaba and 35 slaves of his own. Yancey takes up residence there and quickly blends in to the lifestyle of the southern aristocrat. To give voice to his now outspoken support of slavery, he becomes editor of The Cahaba Southern Democrat, and enters politics, first in the state legislature, then, in 1844, as a member of the Alabama delegation to the U.S. House.

In his personal life, Yancey embraces the “code duello,” which defines “honorable behavior” for men of the South., a how-to series of rules-–how to manage a plantation, treat women and slaves, interact in society, serve one’s country, uphold traditions. Also, how to avenge insults or sleights,

something Yancey does on two noteworthy occasions: first, when he kills his wife’s uncle in a family brawl, which leads to a jail term; and second, in 1846, when he fights a harmless duel with Thomas Clingman, a Whig congressman, who criticizes his speech on the Texas Annexation.

In 1848 Yancey focuses his ire on the continuing push in Congress to approve the Wilmot Proviso.

Like Calhoun, he believes the time has come for the South to take a united stand against all threats to abolish or limit the expansion of slavery. To create this united front, he orchestrates the development of five principles related to the Mexican Cession lands that become known as the “Alabama Platform:”

- Mexico’s 1821 law abolishing slavery must be revoked for the new US territories.

- Settlers must be able to bring slaves into any territory once it is opened up.

- The federal government must protect the rights of slave-holders in the territory.

- Slavery will be legal until and unless a formal state Convention votes to prohibit it.

- Alabama delegates will oppose all presidential candidates supporting either Wilmot or a “pop sov” version that prohibits bringing slaves into any new territories.

Yancey’s demands are all aimed at “rigging” any popular voting in favor of slavery by making it a fait d’accompli in a new territory well in advance of any state constitution or election.

Yancey believes that his plan will accomplish this by first rushing slaves onto farms and plantations in new territories as quickly as possible. Next, he will delay any popular vote until the institution is well established. His premise is simple: Removing slavery once it has taken root will be more difficult than banning it from the start.

Yancey admits that his plan is not the ironclad guarantee the South would ideally seek, but it does build off the Democrat’s “popular sovereignty” platform, while tipping the scales of any live vote in favor of slavery.

The 5-point “Alabama Platform” is approved by his home state legislature on February 14-15, 1848, and Yancey then tries to “sell it” across the South. He succeeds in three other states – Virginia, Georgia, and Florida – and will take his case to the May 22 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore.