Section #4 - Early sectional conflicts over expanding slavery lead to the Missouri Compromise Of 1820

Chapter 40: The “Two Floridas” Acquired From Spain

1513-1818

The Complex History Of La Florida

Before adding Missouri, the landmass of the United States expands again with the acquisition of “the Two Floridas” from Spain.

The history of Florida is mired in the complexities of European colonization and warfare.

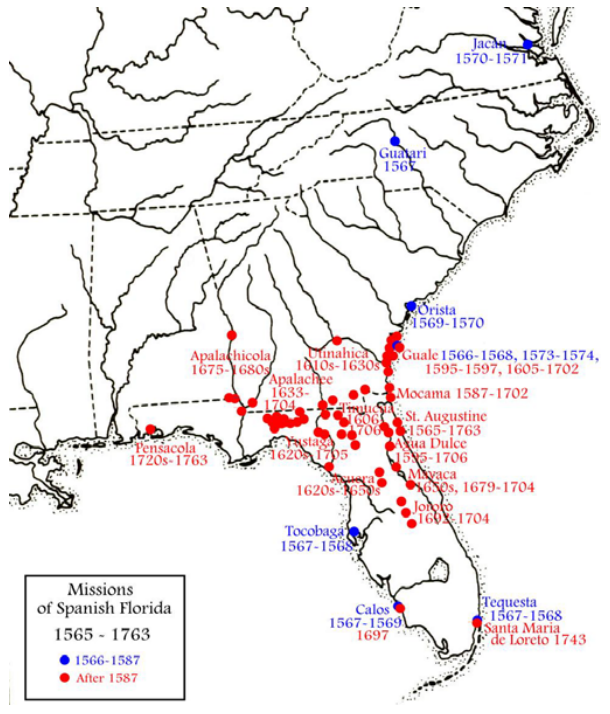

The Spanish explorer, Ponce de Leon, arrives there on Easter Sunday in 1513, and christens it “La Florida,” (“flowering Easter”) in tribute to the traditional feast day celebration. In the 1520’s and 1530’s Hernando DeSoto and Alvar Cabeza consolidate Spain’s claim to the land, and Jesuit missions begin to spring up from St. Augustine on the east coast to Pensacola, 400 miles to the west. But the actual number of settlers remains low over time, in part due to hostility from local Creek and Seminole tribes.

Ownership of La Florida comes into play in 1763, after Britain’s victory in the first global conflict known as the Seven Year’s War. Spain, on the losing side alongside France, has surrendered its control over Cuba, when the port city of Havana falls to the Royal Navy. To regain this, it essentially trades La Florida to Britain in exchange for Cuba, as part of the Treaty of Paris.

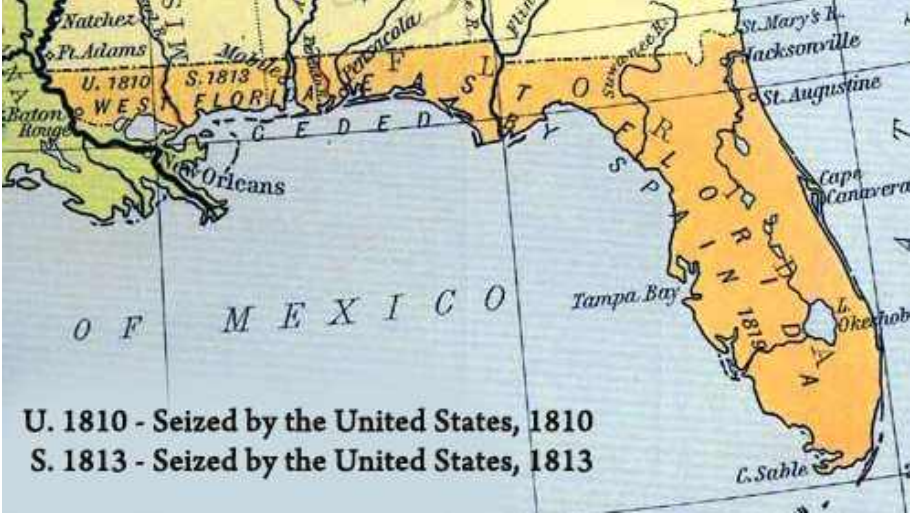

The British immediately divide the territory into two colonies, east and west of the Apalachicola River. West Florida, comprising some 380,000 acres, has its capital in Pensacola; the much larger East Florida, 2.8 million acres, is anchored in St. Augustine. Both are headed by a Governor, and administered along the same lines as Britain’s original thirteen colonies.

A Proclamation issued in 1763 tries to force migration of British citizens into the new Florida colony rather than to the north across the Appalachian range. To sweeten the deal, pioneers are promised generous land grants, and slavery is permitted to draw Southern settlers and crops, especially cotton and indigo.

But British control over the two Floridas is only twelve years old when America’s Revolutionary War erupts.

The early settlers side unequivocally with the Crown, and local militias are called out for defense. When the conflict shifts to the southern theater in 1780, the Floridians are comforted by early victories at Charleston and Savannah. Then comes the stunning defeat at Yorktown in 1781, followed by the 1783 Treaty of Ghent, where America’s negotiators take what they can get: formal recognition of their independence and British land from west of the Appalachians to the Mississippi.

Canada remains in British hands and La Florida is returned to France’s ally, Spain.

In regaining the two Floridas, Spain controls almost all of the critical southern port cities along the Gulf of Mexico, save for New Orleans, which America wins in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Almost inevitably a string of border disputes erupt between Spain and the US, starting in the west.

Jefferson argues that West Florida is actually a part of its 1803 acquisition from France, and Madison supports the 1810 takeover of Baton Rouge. He then orders American troops to secure control over all of West Florida in 1813.

Under Madison, the focus shifts to East Florida, with tensions centering on its status as a haven for run-away slaves from Georgia and South Carolina, and ongoing raids by Seminole tribes north of the border.

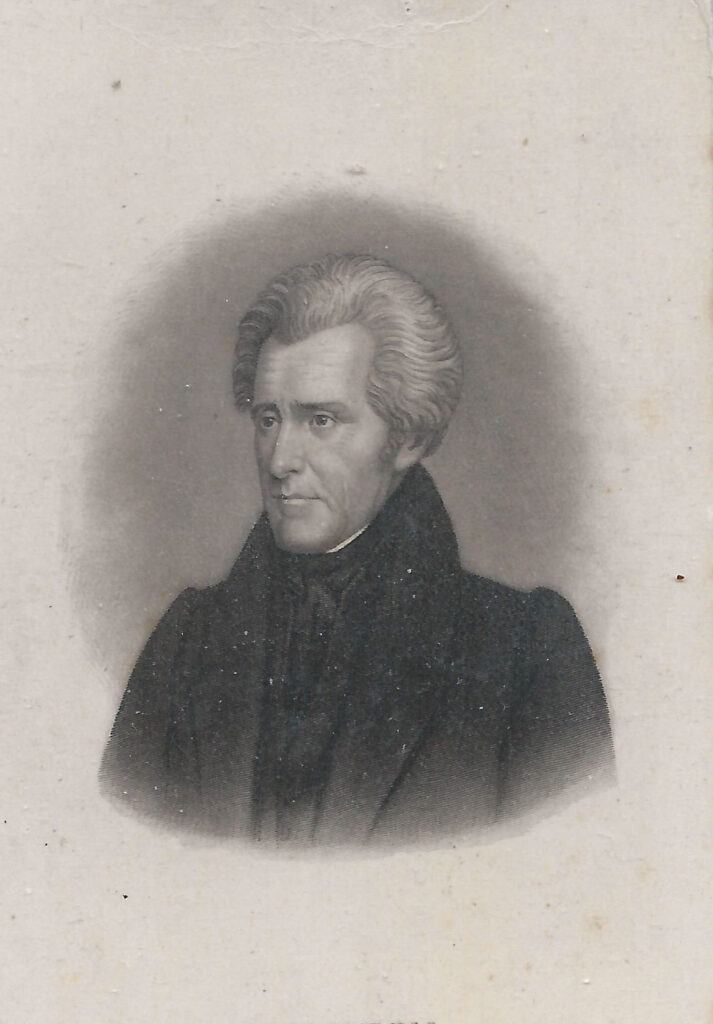

These raids are initially suppressed in 1816 by General Andrew Jackson’s in the First Seminole War.

In 1818 Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, again calls upon Jackson to march into Spanish Florida.

1818

General Andrew Jackson Rampages Across Florida

General Jackson of course has won national fame during the War of 1812 with his landmark victories at Horseshoe Bend and New Orleans, so he is well accustomed to leading troops into action.

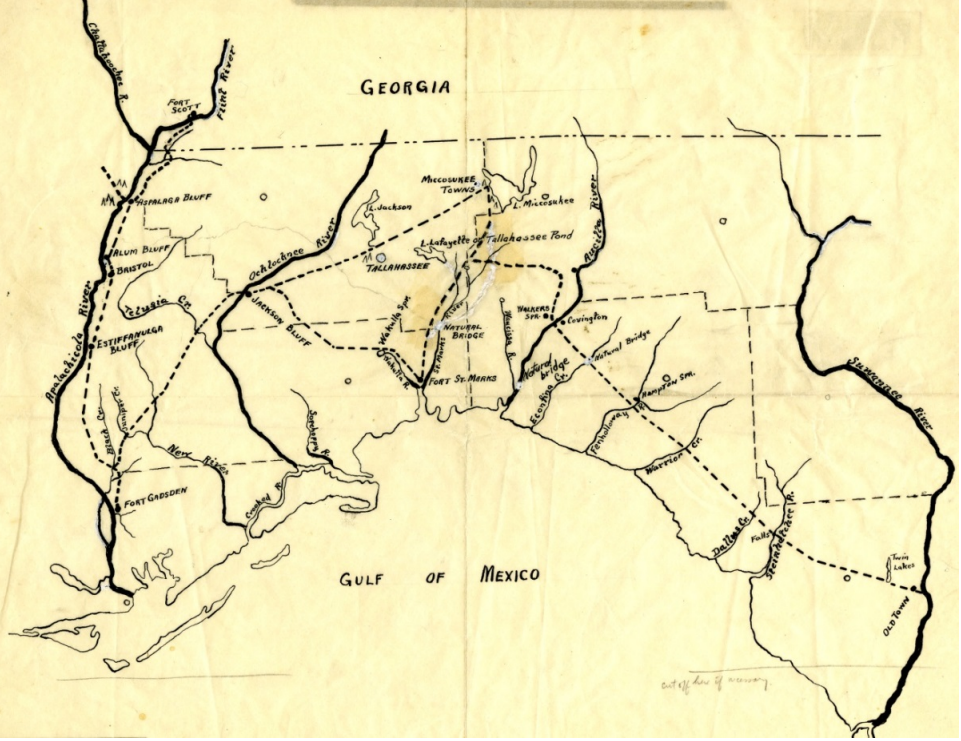

On March 15, 1818, Jackson sets out against East Florida from Ft. Scott (upper left) with a mixed force of some 4200 regulars, militia and friendly Creek Indians. Moving south down the Apalachicola River, he pauses to construct a new stronghold, Ft. Gadsden (lower left), and garrisons some his troops there.

He then swings back up north and east, assaulting and burning an Indian village at Tallahassee on March 31, and taking the town of Miccosukee the following day.

The General continues south to San Marcos de Apalache, a port city on the Gulf of Mexico, home to the Spanish Fort of St. Marks — where he finds two British nationals, Robert Ambrister and Alexander Arbuthnot, who are rumored to be selling guns to the Indians. Jackson sets up a court martial to try both men, who are found guilty. Ambrister is executed by firing squad on April 29, and Arbuthnot is hanged.

After a sweep further east along the Suwanee River, Jackson feels he has accomplished his mission, and heads back west, first to Ft. Gadsden and then into West Florida, were he reduces the Spanish Ft. Barrancas at Pensacola on May 28.

This ends Jackson’s ten-week rampage across northern Florida.

It is followed, however, by a barrage of criticism back in Washington that will forever make adversaries of Jackson and then Speaker of the House, Henry Clay, and some twelve years later divide President Jackson from his then Vice-President Calhoun.

Clay regards Jackson’s executions at St. Marks and his seizure of Pensacola as “acts of war,” carried out in rogue fashion by the General without authorization from Congress, as required in the Constitution.

When Clay’s complaint is discussed within Monroe’s cabinet, Calhoun attempts to dodge responsibility, saying that Jackson exceeded his orders and should be arrested – a political maneuver that Jackson learns of more than a decade later.

Jackson’s successes are again applauded by the public, and he defends himself, arguing that he was acting under direct orders to carry out his patriotic duty.

But Clay is undeterred. He calls congressional hearings to review the Ambrister and Arbuthnot cases and presses to officially censure Jackson.

At this point, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams steps in and argues that his colleagues should back off from their attacks on Jackson.

My principle is that everything he did was defensive; that as such it was neither war against Spain nor violation of the Constitution.

This works, but the General will neither forget nor forgive Clay, and the Speaker will henceforth refer to Jackson as “King Andrew,” ever ready to act above the law.

Their very personal feud will continue all the way up to Jackson’s death in 1845.

February 22, 1819

Spain Cedes Florida To America In The Adams-Onis Treaty

As Jackson is on the march, Adams is continuing to negotiate with Luis de Onis, Spain’s ambassador to the United States, to acquire Florida. Onis is a clever adversary according to Adams:

A finished scholar in the Spanish procrastinating school of diplomacy.

The Minister has long tried to deflect inquiries about surrendering any of Spain’s land holdings in America, be they related to La Florida or to the vast territory west of the Louisiana Territory. But by 1818 Spain’s colonial empire in the western hemisphere is crumbling. One attempt at independence has already been made and turned back in Mexico, and the liberator, Simon Bolivar, is well on his way to ending Spanish rule in South America.

So when Secretary of State Adams approaches Onis again about Florida, the door is opened to resolution.

Onis recognizes that Spain’s military forces in Florida are incapable of controlling the border – either to stop further Seminole incursions into Georgia or to drive out American occupiers. Thus trying to hold on to Florida strikes him as a lost cause.

Instead, his focus turns to protecting Spain’s much more important boundaries in the west – from Texas and Mexico all the way across the southwest to the Pacific coast. The key to this lies in defining exactly where America’s Louisiana Purchase land ends and where Spanish land begins.

Disputes on this have surfaced repeatedly since Napoleon’s 1803 sale – and Adams and Onis begin negotiations far apart on their claims. Adams argues that American land should extend to the Rio Grande River, thus encompassing the province of Tejas. Onis counters by asserting that the proper boundary should be far east, at the Mississippi River.

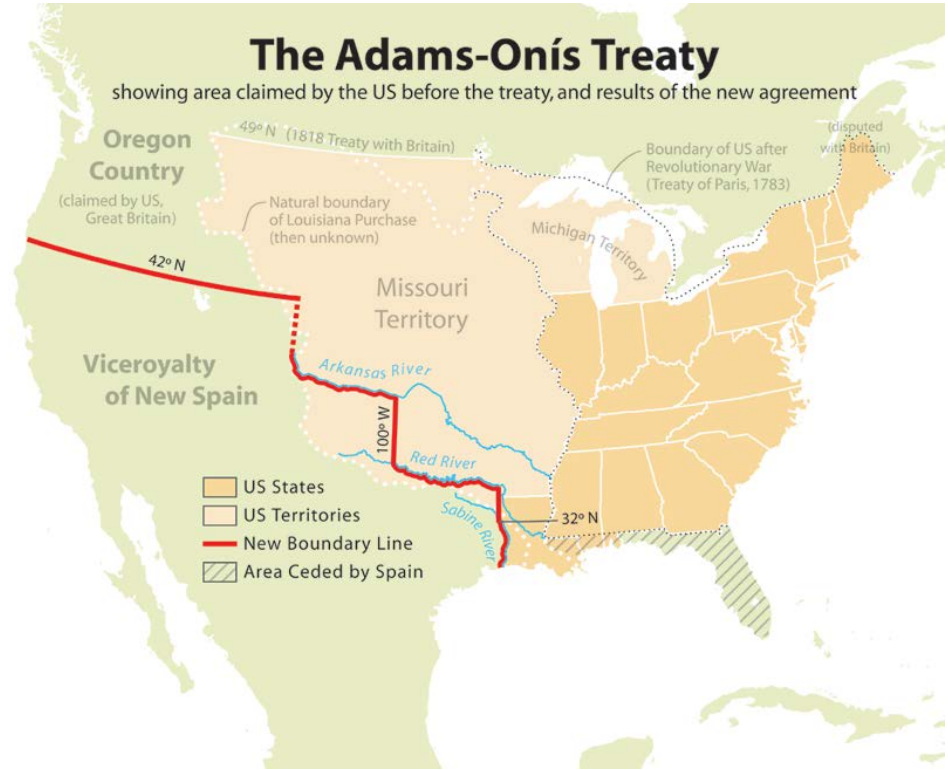

After this difference stalls progress, Adams takes a hard-nosed stance, essentially an ultimatum, “giving” on the Rio Grande proposal, while demanding a line that goes north along the Mississippi, then west on the Sabine and Red Rivers, then north again to the Arkansas, followed by another northward turn to the 42nd parallel and all the way from there to the west coast.

If accepted, such a line would insure that America would become a transcontinental nation, with the Oregon Territory becoming its window on the Pacific.

To further provoke a settlement, Adams writes a long memorandum to the Spanish government in Madrid asserting that Jackson’s actions were in self-defense, and that the “derelict province” of Florida must either be properly policed or ceded immediately.

Spain finally capitulates some nine months after Jackson’s occupation. On February 22, 1819, the Adams-Onis (Transcontinental) Treaty is signed by the two diplomats. The key provisions include:

- Spain cedes West and East Florida to the United States for $5,000;

- The western border of the Louisiana Purchase is resolved;

- Spain gives up its claims north of the 42nd parallel (Oregon);

- The U.S. formally gives up its claims to the Texas territory.

Henry Clay feels that the treaty gives up too much, especially as it relates to Texas, which many have viewed as part of the Louisiana Purchase.

But the Senate passes the Treaty on February 24, 1819, and, under the terms, it goes into effect two years later.

The ever-self-critical Adams will later reflect on his work in uncharacteristically effusive terms:

The Florida Treaty was the most important incident in my life, and the most successful negotiation ever consummated by the Government of this nation.