Section #2 - A new Constitution is adopted and government operations start up

Chapter 15: Hamilton’s Capitalism Sets The Economy In Motion

1755-1804

President Alexander Hamilton: Personal Profile

Once in office, President Washington’s most immediate task lies in setting the U.S. economy in motion – and to do so he turns to Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the U.S. Treasury.

While Hamilton is only 32 years old at the time, he is already a well know figure on the political tage.

His background is unique among the founding fathers.

Born to an unmarried mother on the island of Nevis in the British West Indies, he grows up in poverty and goes to work at age eleven for a trading firm in St. Croix. His success here is remarkable and the New York owners bring him to Manhattan in 1772 to attend King’s (Columbia) College.

When war breaks out, Hamilton distinguishes himself as a soldier, serving over four years as Washington’s aide-de-camp and leading a battalion at the decisive battle of Yorktown. Along the way, he learns that a nation unable to finance a war will be hard pressed to fight one successfully. Thus, under the Articles of Confederation, the government is perpetually unable to secure enough revenue to buy needed arms and to pay its soldiers,

After the war, Hamilton returns to civilian life, mastering the law, marrying into the prominent Schuyler family, and in 1784 founding the Bank of New York, the first in the city.

His fame leads to his attendance at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, where he breaks with his Anti-Federalist colleagues from New York and joins his mentor, Washington, in calling for a strong central government.

He signs the final document, and goes on to author many of the Federalist Papers articles that enable it to be ratified by the States.

After Washington is elected President he calls upon Hamilton to be his Treasury Secretary. His task is to establish policies that create sustained growth in the nation’s economy, while properly funding the revenue needs of the central government and guaranteeing a sound and stable money supply.

Hamilton serves in this job for five years, during which time he sets America on the road to capitalism. Along the way he exhibits his penchant for gathering and analyzing information prior to reaching policy decisions. In the first two years of his tenure, he provides seminal reports to Congress on progress.

Five Key Reports To Congress By Hamilton On The Economy

| Date | Topic |

| January 14, 1790 | First Report on Public Credit |

| April 23, 1790 | Operations of the Act Laying Duties on Imports |

| December 14, 1790 | Second Report on Public Credit |

| January 28, 1791 | Report on the Establishment of a Mint |

| December 5, 1791 | Report on Manufactures |

Hamilton resigns in 1795 after details appear in the press about his extra-marital affair with Maria Reynolds. The two fall in love in 1791 after Hamilton helps her escape from an abusive husband. But James Reynolds learns of the affair and forces Hamilton to make blackmail payments to avoid public embarrassment. When a Philadelphia tabloid publishes the story in 1795, Hamilton is convinced that his political rivals, James Monroe and Aaron Burr, are behind it.

Hamilton challenges Monroe to a duel, which is subsequently avoided. But the damage has been done. Hamilton acknowledges the affair, resigns from his post, and returns to his law practice in New York, with political scores left to be settled in the future.

Despite his departure, Hamilton continues to lead the Federalist Party and shape government policy for another decade. He will essentially bend John Adams’ Cabinet to his will and hurt Adams chances for re-election – then go on to insure that Burr is denied the presidency.

His political conflicts with Aaron Burr will, however, end in tragedy on July 12, 1804, when the sitting Vice-President slays him in a duel.

1789 – 1793

Hamilton And Jefferson Have Different Visions For The American Economy

Jefferson kept one in his home in Monticello, saying: “Opposed in death as in life.”

Within Washington’s cabinet there is immediate friction over the future direction of the economy, which will have much to say about America’s upcoming influence worldwide.

One side of the debate rests with Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of State and Virginia planter, who envisions a nation of “yeoman farmers.” On the other side is the Treasury Secretary, Alexander Hamilton, who favors what will become “industrial capitalism.”

Jefferson’s plan simply involves expansion of the existing agricultural economy. He sees it built around 50 acre farms, operated by an independent and self-sufficient owner, motivated to care for the needs of his family. Each farm would produce food, along with various crops and handmade wares to be exchanged for other goods and services at local markets. Simple bartering is the basis for economic exchange in Jefferson’s model. My bale of cotton for your milled wheat and a leather belt.

This plan, according to Jefferson, would leverage America’s greatest natural strength – its abundance of prime agricultural land, already equal to that of France and 1.5 times that of Britain in 1790. And that is even before casting an eye across the Mississippi River to further westward expansion. All good things will follow if the new national government focuses on acquiring more land and transferring it at modest to migrating settlers. He says this to Madison in a 1787 letter:

I think our governments will remain virtuous for many centuries; as long as they are chiefly agricultural; and this will be as long as there shall be vacant lands in any part of America. When they get piled upon one another in large cities, as in Europe, they will become corrupt as in Europe.

When it comes to optimizing the local economy, Jefferson argues that the individual States are in the best position to tax and spend efficiently against their unique conditions. If a given State wishes to build new roads or open more schools, the ways and means should be left up to them. Likewise on all economic policies related to slavery. The Federal government is too far removed from local realities and must be restrained from interfering with “sovereign state” decisions. So says Jefferson.

Hamilton’s response is outright rejection across the board.

He argues that Jefferson is stuck looking backward to the eighteenth century, when he should be looking ahead to the nineteenth.

Instead of a landscape filled with small farmers bartering crops to sustain their own families, Hamilton imagines the growth of central cities, along with businesses run by “owners” who employ “wage earners,” and provide the public with the full range of goods and services they seek.

Hamilton’s economic vision is influenced by Adam Smith’s 1790 treatise titled, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Smith attacks the old-world system called “mercantilism” in which enterprise is tightly controlled by the state, and fueled by a very limited money supply of gold and silver coins kept largely in the hands of the aristocracy.

To accelerate national wealth, Smith argues that the common man needs to be able to participate in starting his own business. This, he asserts, will benefit society as a whole in two ways:

- To succeed, the businessman will be guided, almost by an “invisible hand,” to provide only those things that society needs in order to progress; and

- To maximize personal wealth, he will rely on “specialization,” inventing the most clever and efficient ways to provide these things at the lowest possible cost.

As these future businesses prosper, so too will all citizens, according to Hamilton – along with the economy as a whole, and America’s standing in Europe.

Hamilton also fundamentally disagrees with Jefferson when it comes to the role of the national government in guiding and supporting economic growth.

Instead of a “hands-off” approach, Hamilton argues that the central government must be actively involved in policies that will enable “capitalism” to succeed. Four of these policies, in particular, will gall Jefferson and his fellow Anti-Federalist supporters:

- Expanding the supply of capital available by printing soft money to supplement scarce minted coins.

- Creating a central U.S. Bank to handle government funds and regulate state banks and the money supply.

- Setting high enough tariffs on imported goods to “protect” the development of American manufacturers.

- Investing national tax dollars in local infrastructure projects that support domestic business growth.

Hamilton’s vision of capitalism is both baffling and threatening to Jefferson.

Small farming and personal bartering are transparent and understandable to the common man. But not so this “capitalism model” with its owners and wage earners, banks and soft money, credit and debt, tariffs and federal government involvement. Won’t these new banks and businesses concentrate great wealth and great power in the hands of a new elite, another form of aristocracy, which would diminish the common man, along with the tenets of freedom and democracy? Won’t they further erode “state sovereignty” and perhaps even threaten the South’s commitment to slavery?

Jefferson’s nation of yeoman farmers vs. Hamilton’s call for new cities, capitalism and industrial commerce.

These two views will increasingly come into conflict in the first half of the nineteenth century. At first they will simply divide a few early industrialists in the northeast from the vast bulk of farmers in the rest of the country.

But as time passed, one region of the country – the South – will become frozen in the old agrarian economy built around slave labor, while the other – the North –will transition to the new industrial capitalism and wage labor.

1792

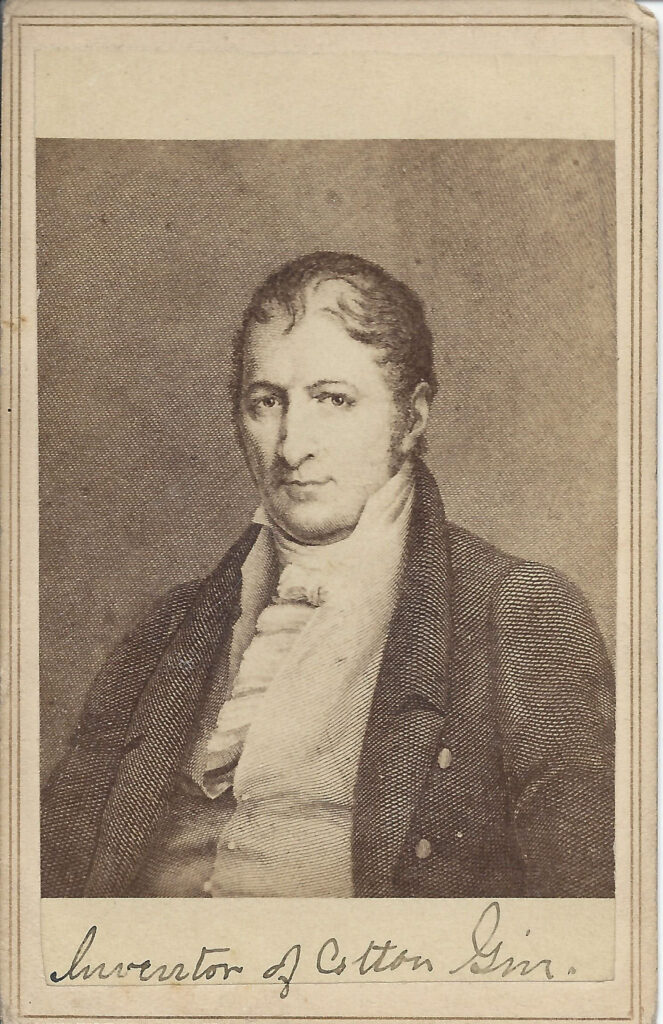

Eli Whitney’s “Gin” Cements Southern Commitment To Cotton

The Southern commitment to agriculture throughout the colonial period centers around it cash crops of tobacco, rice, wheat and indigo.

Meanwhile, cotton production remains minimal and is concentrated along the coastal islands of South Carolina. In 1790, American exports of cotton total only 140,000 pounds, valued at just over $2 million, with almost all of this in the “long-staple” (2 inch fiber) variety.

Its cousin, “short-staple” (1 inch fiber) cotton, is much heartier when it comes to surviving in lower temperature regions — but it has many more sticky seeds per “boll,” and separating these seeds from the fiber by hand is so labor intensive as to be cost prohibitive.

This drawback, however, is about to change.

All because of one Eli Whitney, a Westborough, Massachusetts man, who tinkers with nail manufacturing as a youth, graduates from Yale University and, after visiting a plantation in Georgia in 1792, invents and patents his “cotton gin.”

Whitney’s “gin” (short for “engine”) is ingenious. It removes seeds from cotton lint at 50 times the speed of human hands, and, in turn, it enables the profitable planting of short-staple cotton across the South from Virginia westward.

Almost immediately the production and sale of cotton skyrockets – and, as it takes off, it also dawns on plantation owners that they have a “second crop” capable of very high demand and very high prices.

That “second crop” lies in breeding and selling excess black enslaved people to new masters.

1789 – 1793

Hamilton Agrees To Cover All Federal And State Debt

In 1790 Washington has turned to Hamilton, not Jefferson, to fix the nation’s broken economy and get the new government out of debt.

On September 11, 1789, the Senate confirms Hamilton’s appointment as Secretary of the Treasury, which consists of 40 staffers (tenfold the 4 employees approved for Jefferson at State).

Hamilton faces enormous opening challenges.

The first is the huge debt from the six year war with Britain.

According to “The First Report On Public Credit” published on January 14, 1790, the United States owes a total of $54 million — $13 million to foreign interests and another $41 million to domestic investors. Individual States owe an additional $14 million in total.

These debts are owed to wealthy men, Americans and many foreigners, who have “bet” their money on an eventual American victory over Britain in the Revolutionary War.

Their bets are made in the form of “bonds” or IOU’s, typically constructed as follows:

- In exchange for my loan today of $900 dollars…

- The government promises to pay me back $1,000 dollars on this later date.

While the above bond would be said to have a “par value” of $1,000, the “holder” might decide to sell it to another investor either above or below its face/par value – depending on the outlook for the American cause at any point in the war. In 1790 many of these bonds are owned by secondary investors who purchase them at amounts well below their par value.

Hamilton knows that the United States cannot immediately pay off this entire $68 million debt, given a total economy (GDP) valued at only $190 million.

But bold action is integral to Hamilton’s persona.

So he quickly assures bond-holders that the Treasury will pay all of them back, at full par value. He makes this pledge in spite of resistance from Anti-Federalist factions within Congress and others who argue the debt should be substantially reduced, since secondary speculators had purchased many of the bonds at prices well below their par value.

But Hamilton beats them back, on the grounds that recalculating bond values would be detrimental to securing future loans.

Many of these same critics also oppose his plan to assume the State’s $14 million in debts, for fear that this would further concentrate power with the central government. They concede after Jefferson, Madison and Hamilton work out the so-called “dinner party compromise,” whereby

they reach an agreement on moving the capital from Philadelphia, south to Washington City, by 1801.

At this point, Hamilton has assumes all U.S. debt under his federal Treasury. Now all he needs to figure out is how to pay it off.

1789 – 1793

The First Taxes Are Levied On Foreign Imports And Domestic Spirits

Since the 1787 Constitution expressly forbids anything like an income or property tax on individual citizens, Hamilton begins his quest for funding with a “tariff” to be imposed on goods entering American ports.

Once he has settled on the idea of the tariff, the challenge then becomes one of deciding which items to tax and at what rates. The debates here produce an immediate firestorm in Congress, with each industry and state attempting to lobby on behalf of its own economic interest.

The most intense conflicts center on tariffs that appear to favor one section of the nation at the expense of another. Goods made from iron are one example – with the North wanting a high tariff to “protect” their start-up smelting operations and the South seeking a low tariff on imported necessities such as nails, horseshoes and the like.

In the end, the Tariff and Tonnage Act of 1789 lays out a simple, compromise formula:

- American ships entering U.S. ports shall be taxed at 6 cents per ton of cargo; and

- Foreign ships shall be taxed at 50 cents per ton.

This tariff provides 85% of the total revenue Hamilton is able to collect to fund the new federal government. The other 15% comes from excise taxes (mostly on whiskey and tobacco) and from the sale of public lands.

The Tariff gives Hamilton and the country the revenue stream it needs to begin to pay down its debts and to cover its expenses.

At the same time, however, it also produces the first threat to secede from the Union, in this case issued by a founding father, Senator Pierce Butler of South Carolina.

Butler is particularly critical because he views the tariff as damaging to the profitability of what is becoming the South’s key industry – production of raw cotton,

High tariffs on finished goods from the UK increase their retail prices and therefore reduce sales demand in the U.S. In turn this reduces UK demand for our cotton. So a win for the new northeastern mills comes at the expense of southern cotton farmers.

This complaint about tariff rates on cotton imports will rage off and on for the next three decades, culminating in the Nullification Crisis of 1830.

1789 – 1793

Hamilton Floats U.S. Treasury Bonds To Add More Revenue

Hamilton’s second source of government funding comes in the form of IOU bonds, similar to those used by the colonialists to finance the war.

These are now cast as “U.S. Treasury Bonds.”

He offers these to investors – along with a promise to redeem them at a future date, paying the face value plus a rate of interest to be established on a daily basis, depending on economic conditions.

“You lend the government $100 today and it will pay you back $104 in a year.”

Hamilton puts these Treasury Bonds up for auction to investors six times every week, and because they are backed “by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government,” they quickly become popular.

Investors christen these U.S. Treasury notes as “The Stock.”

And they begin to meet informally in New York at the Merchant’s Coffee House on Wall Street to buy and sell “The Stock,” with help from brokers, or “stockjobbers,” who manage the transactions.

By 1792 a formal New York Stock Exchange is established to quote prices on five different securities, all bank bonds.

Over time shares in corporations are added to the menu and the New York Stock Exchange becomes a weathervane on the health of the American economy.

The Anti-Federalists attack both the tariff and Hamilton’s Treasury Bonds, which they see as a spend now-pay later scheme that will run the country into long-term debt and insolvency.

1789 – 1793

Hamilton Turns His Attention To The Money Supply

With his plan in place to secure sufficient funding to run the federal government, Hamilton turns to jump starting the nation’s economic growth.

He believes the key to this lies in getting sufficient capital (money) into the hands of clever men who are intent on starting up their own businesses – to mill grain or make rum, to transport goods over roads or waterways, to open store-fronts in small towns or big cities.

The money itself must be simultaneously in abundant supply and viewed as trustworthy in terms of value, so that enough entrepreneurs can access what they need, and transactions can be easily facilitated. This poses a problem for Hamilton:

- The public has great faith in the value of minted gold and silver coins, but there is not enough supply to cover the needs of prospective businesses.

- Conversely, the option to coins are “bills of credit” or “Continentals,” issued by state banks during the War in such out-of-control inflationary quantities during the War that no one trusts them.

Since America is still some 60 years away from discovering large gold and silver deposits in the West, Hamilton will have to make do with “soft money” for the time being.

His challenge then lies in restoring confidence among a skeptical public toward banknotes. As he says:

There is scarcely any point in the economy of national affairs of greater moment than the uniform preservation of the intrinsic value of the money unit. On this, the security and steady value of property essentially depend.

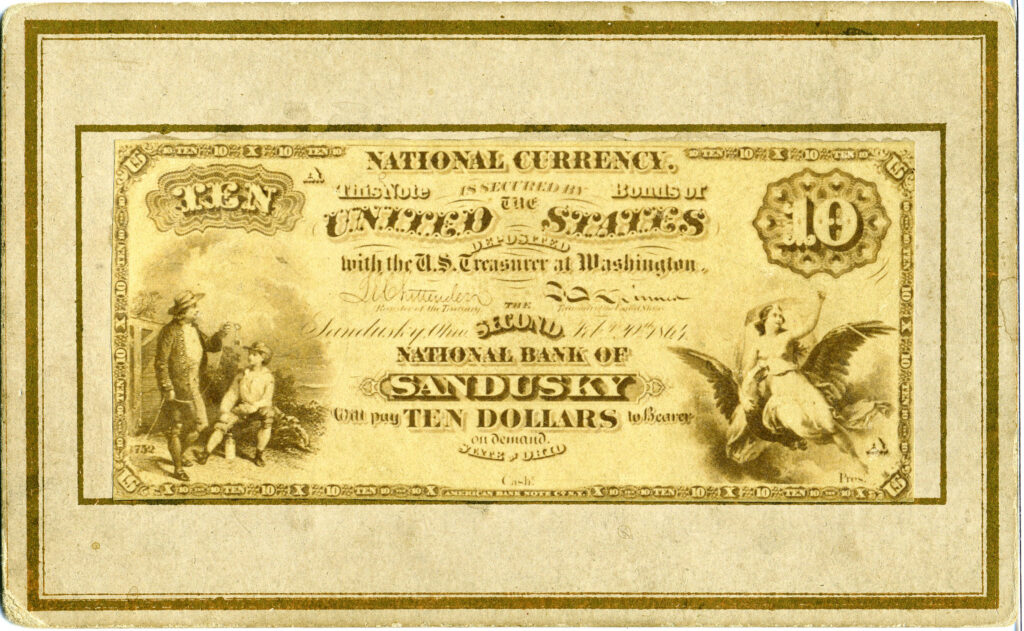

To restore trust, Hamilton will try to insure that those entities handling “bills of credit” – largely unchartered state banks – maintain a sufficient supply of gold or silver coins on hand to “back up” their value. He decides that a ratio of 3:1 (soft money to hard money) will work.

For every $3.00 worth of banknotes in circulation the “bank” must maintain $1.00 worth of coins.

To enforce this ratio, he promises to bring “fraud charges” against anyone refusing a customer’s “demand” to exchange banknotes for gold or silver coins on a dollar-for-dollar basis. As time passes this “exchange pledge” will appear on many banknotes:

Ten Dollars In Gold Coin Payable To Bearer Upon Demand

He then adds to his “enforcement power” by another move the Anti-Federalists regard as further intrusion on State sovereignty – creation of the First Bank of the United States.

Ongoing

Sidebar: How Banks Work And How They Fail

As a banker himself, Hamilton ultimately understands how banks are supposed to function.

Their primary role is to distribute capital/money to people who need it to start up or sustain their businesses.

Bankers think of these as “investments.”

The most common form of investment is a “Loan” made by a bank to someone who needs money (e.g. a farmer requiring $20 to purchase seed) in exchange for a promise to pay it back one year later with “interest” (e.g. after his crop of grain sells, the farmer pays $22 to the bank ).

Another form of “investment” might involve a direct purchase by the bank of an asset that appears likely to “appreciate” (increase) in value. For example, a bank might decide to buy up land out west at $1 per acre, believing it can later be sold for $2 per acre – delivering a handsome profit.

Bankers are also always interested in expanding the amount of money or coins they have available to make these investments.

They can accomplish this by convincing individuals or businesses to make “deposits” in exchange for “interest” paid over time. For example, an individual or merchant with a spare $20 may “deposit” it today in a bank in exchange for a promise to get $21 back in “principle and interest” one year hence.

To pay this “interest,” banks expect to “invest” this $20 in businesses or asset purchases that “return” more than the $21 they will owe their depositors.

In the vast majority of cases, this banking system works out to the benefit of all sides. Individuals and businesses get access to the money they need and pay back their loans. Banks invest wisely, make a profit and pay back the principle and interest they owe to depositors.

But this is not always the case. “Capitalism” involves “risks” and, as Hamilton knows, banks are perpetually subject to these. They typically involve an “unexpected outcome” affecting a given investment.

A drought strikes, and the farmer, losing his crop, is unable to pay his loan back to the bank as planned. Perhaps the bank forecloses (seizes) his land instead. The value of the land bought by the banker drop sharply, creating a loss and making it impossible to pay back depositors when they come to collect. Perhaps the bank closes as a result, with all depositors losing their principal and interest.

Or the “spread” between the “interest” being paid out to depositors vs. collected from borrowers suddenly turns against the bank. For example, the bank finds that it has made too many loans charging only 2% interest, while simultaneously promising too many depositors 3% interest – the “spread” has turned against them. Or, suddenly, inflation causes new people to demand 4% interest to make deposits, causing sudden withdrawals of cash.

All these banking risks are real and, when they occur, the entire economy can be adversely affected.

What’s even wore is that the “profit motive” in banking, as in any form of capitalism, can easily get out of hand.

“Defalcation” – misuse of funds by bank personnel — occurs from time to time, often in the form of embezzlement. But the effects here are local and limited.

The banking risks that really impact the nation’s economy typically involve wild “speculation” in supposedly sure-fire investments. In the antebellum U.S., this speculation will often center on the purchase of new land in the west, where expected jumps in per acre prices fail to materialize and “bankruptcy” follows – along with “panic runs on banks” by depositors hoping to retrieve their deposits in time.

As America’s first Treasury Secretary tries, like his successors, to steer between the rewards and risks associated with the banking industry.

1791

The Controversial First Bank Of The United States Is Chartered

Hamilton’s First Bank of the United States, or BUS, is chartered by Congress on February 25, 1791. It is a “private corporation” owned not by the government, but by individual stockholders expecting to make a profit on their investments.

This charter calls for it to begin with $10 million in capital, allocated across 250,000 shares of stock, offered at $400 apiece. The federal government owns $2 million of this stock, with the remaining $8 million owned by outside stockholders, each required to make 25% of their buy-in payments in gold or silver specie.

Hamilton sees his “BUS” as having two main public sector functions:

- First, to handle the government’s monetary needs – taking in federal revenue and paying bills to cover federal spending — while operating at arm’s length to avoid conflicts of interest.

- Second, to help “regulate” the banking system and money supply across the states.

“Bank regulation” under Hamilton will take several forms. Formal “chartering” of state banks will accelerate – from a total of three in 1790 to over 300 three decades hence. The U.S. Mint will take control over setting and insuring weight standards and values for gold and silver coinage. The BUS will also flex its muscles with state banks who appeal to it for cash loans. Those local banks in compliance with the 3:1 soft to hard money target, will get loans at lower interest rates; those out of compliance, will suffer higher interest charges or be turned down entirely.

Needless to say, these attempts at regulation are viewed as unfavorable intrusions on state sovereignty by the Anti-Federalists, who express a host of concerns:

- Isn’t the “fractional formula” a fraud, designed to print imaginary money?

- Won’t this system of phony money and usury lead on to wild speculation by banks?

- Who are the people profiting from these banks – and how can corruption be avoided?

- What happen if everyone wanted their money at the same time, in a panic?

To rein in the power of the BUS, they add a series of constraints to the 1791 charter:

- The charter will last only 20 years, expiring in 1811.

- The BUS must be run as a private company, not another “branch” of government.

- The directors of the company must be rotated after fixed terms.

- No foreigners will be allowed to own stock in the bank.

- The BUS cannot purchase any government bonds.

- The Treasury Secretary may audit the BUS books at any time.

- While it would be the only “federal” bank, states could open as many banks as desired.

Jefferson’s distrust of the BUS – and of Hamilton – is unwavering. He writes:

Hamilton’s financial system… had two objects; 1st, as a puzzle, to exclude popular understanding and inquiry; 2nd, as a machine for the corruption of the legislature; for he avowed the opinion, that man could be governed by one of two motives only, force or interest; force, he observed, in this country was out of the question, and the interests, therefore, of the members must be laid hold of, to keep the legislative in unison with the executive.

The BUS also ruptures James Madison’s commitment to the Federalist cause. Henceforth he will align himself with Jefferson in what will become the Democratic-Republican Party.

When political power eventually shifts to Jefferson, he will de-charter the BUS and do away with many of the banking controls initiated by Hamilton.

These moves, however, will backfire over time, as banks veer out of control every two decades or so, driven by wild speculation in search of windfall profits, and accompanied by public panic and often prolonged economic downturns for the nation.

1755-1804

Assessing Hamilton’s Influence

Alexander Hamilton’s effect on the U.S. economy will prove profound.

In the short run, the combination of tariffs and excise taxes, along with the issuance of the first U.S. Treasury Bonds, moves the nation out of debt – despite his bold agreement to assume the state’s red ink and to pay full par value to War investors.

By the time he resigns in 1795, America enjoys the highest credit rating in Europe, with its bonds often selling well above par value.

He makes remarkable progress toward his goal of “insuring the intrinsic value of the money unit.”

The U.S. Mint standardizes and controls the weight of gold and silver in America’s coinage.

He begins to rebuild confidence in “soft money” banknotes by assuring the public that “on demand conversion into equivalent value coinage” is the law of the land.

His efforts to tighten regulations on the banking industry also pay off. The number of officially “chartered” state banks grows. His 3:1 soft-to-hard money ratio “multiplies” the capital in circulation without letting the number of banknotes expand to levels where they are de-valued. He is also able to enforce the 3:1 ratio by varying the interest rates his BUS charges state banks on loans.

The BUS itself functions about as Hamilton hopes. Federal government revenues flow in and bills are paid out in orderly fashion, signals of a stable and confident nation.

But above all else, Hamilton ushers in the system of “capitalism” that will enable America to build a modern economy which eventually become the envy of the world.

While his career is brief, he goes down in history as the father of American banking and capitalism.