Section #19 - Regional violence ends in Kansas as a “Free State” Constitution banning all black residents passes

Chapter 214: William Walker’s Filibuster Of Nicaragua Collapses

October 22, 1855 – July 12, 1856

Walker’s Grip Over Nicaragua Slips After He Crosses Cornelius Vanderbilt

While Buchanan shifts his attention to Kansas, the 18 month reign of filibusterer William Walker to expand slavery into Nicaragua comes to an end.

The latest Walker affair takes shape back on October 22, 1855, when he executes the top Legitimista government official in Grenada and gains absolute control over the nation, behind a new puppet president. To the dismay of the Nicaraguans, however, his goal is not to reform the country, but to “Americanize” it. He declares English the official language, introduces a new currency, reinstates the practice of slavery, and aggressively seeks US immigrants. Gringos patrol the streets:

Taller men, of fairer hue and heavily bearded, wearing wide-brimmed wool hats, blue flannel shirts, and corduroy or jean trousers tucked into heavy boots, with a brace of pistols and a bowie knife in each belt and a trusty rifle on each right shoulder, were now the masters of Granada. It seemed that a new civilization was about to be engrafted upon the older and decadent one.

Needless to say, this American take-over of their country is anathema to the Nicaraguans, and resistance groups form up, especially under the Legitimista party leader, Colonel Jose Dolores Estrada.

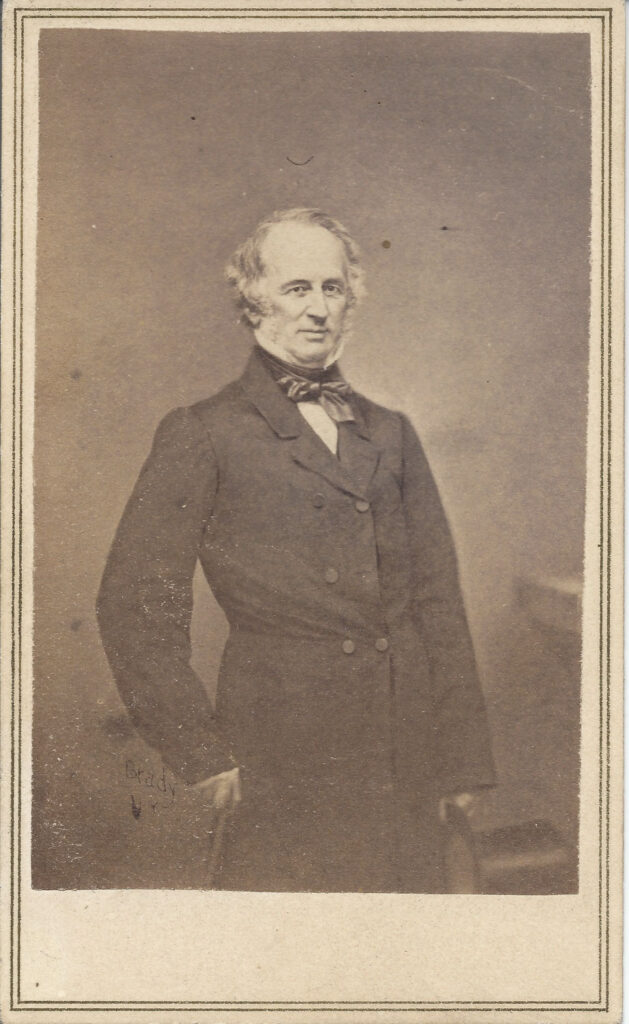

Walker temporarily fends off Estrada, but then makes a fatal mistake by rescinding an 1849 agreement with the “American Transit Company” in a corrupt deal with the firm’s San Francisco agent, C.K. Garrison, and his banker friend, Charles McDonald. In exchange for cash to run his government and help with U.S. recruiting, Walker gives the two men free reign over the transit line’s property and operations – which happen to be owned by the sixty-six year old New York tycoon, Cornelius Vanderbilt. When he hears of the sell-out, the ”Commodore” tells Walker:

I won’t sue you, for the law is too slow. I will ruin you.

Vanderbilt’s agents immediately go to work on convincing the leaders of countries bordering Nicaragua that Walker intends to invade and take them over, The strongly conservative government in Costa Rica is first to respond, readying an invasion force of its own. In typical fashion, Walker plunges ahead to meet them, sending his French and German mercenary units across the southern border and into Costa Rica. They are, however, routed there on March 20, 1856, at the battle of Santa Rosa, with 59 men killed in action.

Walker next learns that coalition troops from Honduras, Salvador and Guatemala are also gathering along his northern border, and, when he sends men there to meet them, the Costa Ricans cross into Nicaragua from the south and score another victory on April 11, 1856, at the Second Battle of Rivas.

Despite these setbacks, Walker holds a fraudulent election and declares himself President of Nicaragua on July 12, 1856. Among his first moves is the creation of a new flag with a five pointed red star acknowledging his intent to eventually unite Costa Rica, Honduras, Salvador and Guatemala with his own Nicaragua.

But the noose around his neck continues to tighten.

May 1, 1857

The Filibuster Collapses After Eighteen Months In Power

On July 18, the neighboring nations agree to join forces to oppose Walker and return Patricio Rivas to office. Vanderbilt also continues to send cash into Costa Rico to undermine the filibuster by reclaiming his Transit Company property. A raid at Hipp’s Point, near San Juan del Norte, recaptures several of the Commodore’s Lake Nicaragua steamships, and cripples Walker’s major conduit for securing new U.S. fighters.

Foreign troops also continue to pour into the Legitimista base at Leon. On September 14, 1856 his Lieutenant, Byron Cole, suffers a major loss to a coalition army under Colonel Estrada at the Battle of San Jacinto, near Managua. Another crushing loss follows three months later, on December 14, 1856, when Henningsen flees the important city of Grenada after losing 60% of his 270 man force to capture, wounds and disease during a prolonged siege. As a final symbolic gesture, he burns the city to the ground before his escape.

With Grenada lost, the town of Rivas becomes the last bastion for Walker’s remaining forces, and he attempts to hold it against a determined siege by his many foes. He does so through January and February of 1857 despite dwindling supplies and growing hardship.

On March 23, the coalition army attacks Rivas and Walker’s remaining force of 322 “fit-for duty” troops. By March 27, the defenders are eating mule meat to keep from starvation. The final skirmish occurs on April 11, after which the grinding siege resumes.

The end comes through intervention by the U.S. Navy. The sloop St. Mary’s arrives offshore off St. Juan del Sur, under the command of Charles Henry Davis, with orders to evacuate any American citizens caught up in the conflict. On April 24, women and children are removed from Rivas under a flag of truce.

Walker balks at his own departure, until Davis informs him that the reinforcements he expects have turned back to America. The two sides then meet with Davis as mediator, and a truce is signed. At 5:00pm on May 1, Walker offers a farewell address to his remaining soldiers in the plaza, before turning his garrison over to Davis for a formal surrender. In a final gesture of defiance, however, he manages to spike all of his cannon and blow up his remaining munitions.

A total of 463 Walker supporters are taken into custody at Rivas – down from the peak contingent of 1,026 he has in March. They are eventually returned to California on a separate vessel, well after Walker and his officers have departed.

The filibuster is now over. Once again Walker has succeeded in gaining military victories that place him in a position of power in a foreign nation – and once again he has failed to command a large enough body of fighters and administrators to sustain his rule.

Based on records kept by Henningsen, his army never exceeds 1200 men at any time during the occupation.

Sidebar: The End Of William Walker And American Filibustering

Upon his return to America, the ever brash Walker goes on a lecture tour, recounting his Nicaraguan tales to cheering audiences. He blames his defeat on a lack of U.S. support, and begins recruiting another invasion force.

In November 1857, he sails out of Mobile Bay with 270 followers, headed back to Nicaragua. When he lands at San Juan del Norte, however, he is arrested by U.S. Marines under Commodore Hiram Paulding, and returned home. While President Buchanan chastises Walker, he also sends a message to the Senate on January 7, 1858 that is critical of Paulding’s intervention.

I herewith transmit to the Senate a report from the Secretary of the Navy…containing the information called for by the resolution of the Senate of the 4th instant, requesting me “to communicate to the Senate the correspondence, instructions, and orders to the United States naval forces on the coast of Central America connected with the arrest of William Walker and his associates,” etc ..In submitting to the Senate the papers for which they have called I deem it proper to make a few observations.

In capturing General Walker and his command after they had landed on the soil of Nicaragua Commodore Paulding has, in my opinion, committed a grave error.. The error of this gallant officer consists in exceeding his instructions and landing his sailors and marines in Nicaragua, whether with or without her consent, for the purpose of making war upon any military force whatever which he might find in the country, no matter from whence they came.

It is quite evident, however, from the communications herewith transmitted that this was done from pure and patriotic motives and in the sincere conviction that he was promoting the interest and vindicating the honor of his country.

Despite his conciliatory remarks toward the “gallant” Paulding, Buchanan relieves him of command and forces him to retire at fifty-eight. (He will, however, be restored to duty in 1861 by Lincoln.)

Meanwhile Walker is once again tried for violating the 1818 Neutrality Act, and once again acquitted.

This allows him to pursue what has now become an “obsession” for the 34 year old adventurer — “Americanizing the Five Nations” of Central America.

He is back at sea in the Fall of 1860 with a shipload of raiders, intent on storming into Honduras. This move is thwarted by a British Royal Navy ship which, instead of returning Walker to the United States, turns him over to the Hondurans.

His protest – “I am the President of Nicaragua” – is ignored, and on September 12, 1860, William Walker is marched into the plaza at the city of Truxillo, tied to a chair, and shot dead by a firing squad of barefoot soldiers.

Thus ends the amazing 36 year adventure of “Colonel Walker, the grey-eyed man of destiny.