Section #4 - Early sectional conflicts over expanding slavery lead to the Missouri Compromise Of 1820

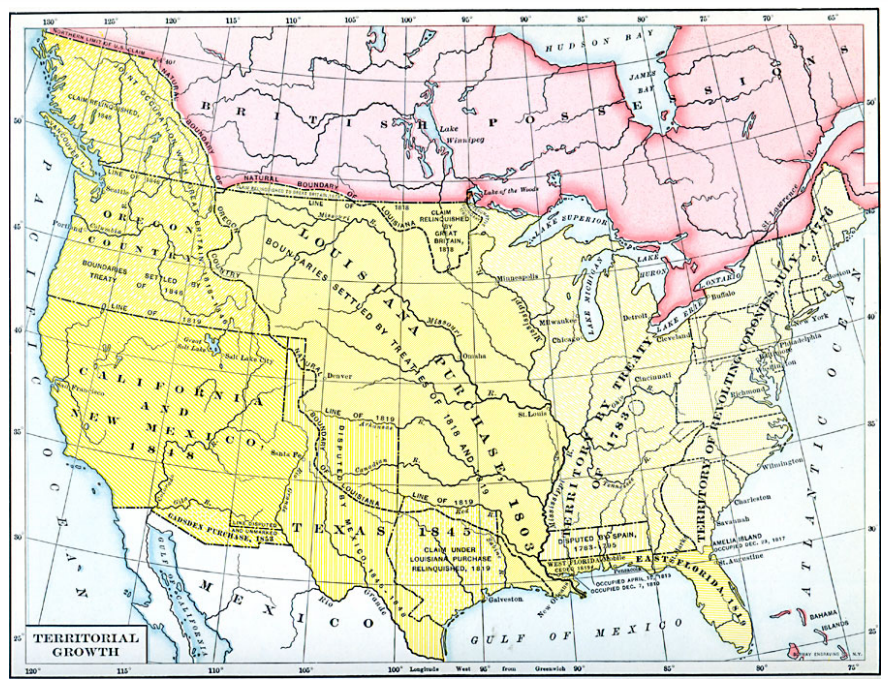

Chapter 37: Westward Expansion Re-Opens Conflicts Over The Destiny Of America’s Blacks

1787 Forward

New States Must Write Constitutions For Admittance To The Union

By the time Napoleon’s attempt to conquer Europe ends, America’s attempt to expand westward is already well on its way.

In 1775 Daniel Boone has crossed the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky in search of creating a 14th colony he calls Transylvania. He is followed in turn by many other western explorers.

The rugged Meriwether Lewis and his aristocratic partner William Clark voyage down the Ohio River, up the Missouri, across the Rocky’s and the Columbia River, and to the Pacific in their 1804-1806 expedition.

In 1805 General Zebulon Pike heads north along the Mississippi River to discover its headwaters in Minnesota, followed by his 1806-1807 expedition southwest into New Mexico and Colorado.

To the north, the fur trader, John Jacob Astor, has traversed the Canadian border from east to west, with an outpost established in 1811 on the Pacific coast in Oregon at Ft. Astoria.

By 1815 then, American settlers are primed to pack up their families and possessions and move en masse to the western territories.

This migration brings with it a host of issues for federal officials, beyond surveying, pricing and recording sales of the new lands. The most challenging relates to the process by which a new territory will achieve statehood and, in turn, be admitted to the Union.

As of Madison’s first term, a total of four new states have been admitted, west of the Appalachians – Kentucky (1792), Tennessee (1796), Ohio (1803), and Louisiana (1812). Each has reached a threshold population level within its borders, held a convention to draft a constitution, had it approved by a local vote, and applied for acceptance to the federal Congress.

On the surface this process appears clear and simple.

But in practice, the task of arriving at a state constitution forces the settlers in each state to deal with the same thorny issue that almost sabotaged the founding father’s efforts in 1787 – namely, how to deal with black people within their borders, be they enslaved or free.

Resolution is, of course, easy in the South. About-to-be states like Mississippi (1817) and Alabama (1819) will build their economies around the need for enslaved black people – to work their existing plantations, and to be bred for sale to those hoping to start-up new plantations.

In the North, however, where slavery is already banned, the issue becomes one of how the dominant white settlers intend to deal with freed blacks who hope to settle in the new states.

The answer will quickly become evident in language written into the initial state Constitutions for Ohio (1804), Illinois (1816) and Indiana (1818).

1804

Ohio Takes The Lead In Trying To “Cleanse Itself” Of All Blacks

Ohio is the first “western state” to express its views regarding the presence of blacks within its borders.

Under the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, slavery is banned in Ohio, although masters are still allowed to come and go with “their property.” But it is the body of “freedmen” who might wish to take up permanent residence in the state that most troubles the white settlers.

To deal with what they regard as this “perceived threat,” Ohio first passes a series of “black codes” aimed at “cleansing” the state of its freed men. The centerpiece of an 1804 bill sets up two hard-to-meet requirements for all blacks seeking permanent residence:

- Produce court papers proving they are free rather than run-away slaves; and

- Post a $500 bond backed by two people to guarantee their “good behavior.”

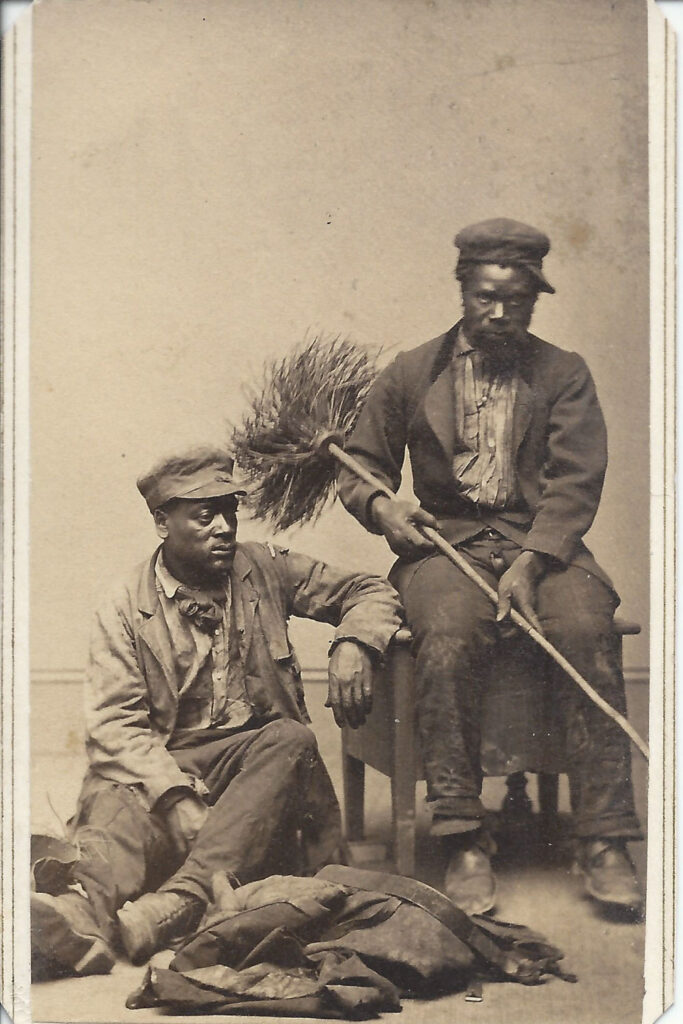

Beyond these hurdles and humiliations, free blacks in Ohio experience the same daily deprivations heaped upon their brethren back east – segregation, poor housing, and the lowliest jobs, little to no education.

The message here from white Ohioans is obvious: “blacks keep out.”

It is overlaid by the threat of physical violence, most evident along the banks of the Ohio River, where black refugees from Kentucky – slaves or freedmen – hope to cross to a semblance of freedom.

As one self-defined guardian of the border puts it:

The banks of the Ohio…are lined with men with muskets to keep off emancipated slaves.

1813

Black Abolitionist James Forten Pleads For Assimilation

In the face of these cleansing efforts, James Forten becomes one of the first blacks to issue an emotional plea to white men to look into their hearts and put an end to their prejudices.

Forten’s amazing life stands as a symbol of free blacks capable of making their own way in a white dominated society.

He is born to free black parents in Philadelphia on September 2, 1766. By age eight, he is attending a Quaker school while working alongside his father in a sail-making business. He volunteers in 1780 to serve in the Revolutionary War, and ends up on a privateer, which is captured at sea by the British. After refusing to pledge allegiance to the crown, he spends eight months on a prison ship before being exchanged.

After the war, Forten works briefly in London’s shipyards before returning home to capitalize on his experience as a sail-maker. He rejoins his old firm in Philadelphia, rises from one job to the next, and in 1798, when the owner retires, he is asked to stay on and oversee the operation.

When Forten devises a new sail that facilitates greater speed and maneuverability, customers begin to flock to his loft. In 1801, at age 35, he becomes its outright owner. His business employs some 30 workers, a mix of whites and black, who are expected to comply with his rigid standards, including punctuality and dedication at work, along with abstinence and regular church attendance.

During the War of 1812, he again exhibits his patriotism by recruiting some 2500 blacks to defend Philadelphia against a possible invasion by the Royal Navy. They construct defensive fortifications along the Schuylkill River and prepare for militia duty.

By the end of the war, the demand for his unique sails makes black James Forten a wealthy man.

Once in possession of capital, Forten follows Alexander Hamilton’s admonitions by leveraging it. In his case this involves investing the money he has made from sail-making in Philadelphia real estate and railroad start-ups, with both rapidly appreciating in value.

Forten is remarkable not only for his business acumen, but also for his commitment to black freedom and eventual citizenship. After many discussions with Cuffee about repatriation, he decides that America, not Sierra Leone or Liberia, should be the proper home for future generations of blacks. With that goal in mind, he begins to act on behalf of needed reforms here in America.

Like his fellow Philadelphian, the Reverend Absalom Jones, Forten recognizes that influencing the political process will be crucial to bettering the lives of freedmen and slaves.

In 1813 he learns that the Pennsylvania senate is considering a bill mimicking efforts in Ohio and Indiana to effectively “cleanse” the state of its free black population. This would be accomplished through an outright ban on allowing any new free blacks from settling in Pennsylvania. Forten decides to speak out against this act, and he does so by publishing his Letters From A Man Of Color On A Late Bill Before The Senate Of Pennsylvania.

The five letters stand as a plea to white men of integrity to abandon their unholy abuses of black people and to grant them the liberty and rights they are due as Americans. In many ways Forten’s sentiments and tonality foreshadow a comparable appeal, sixteen years hence, by the Boston freedman, David Walker.

Forten rejects outright the popular notion that blacks are somehow a different species from whites.

Are we not sustained by the same power, supported by the same food, hurt by the same wounds, pleased with the same delights, and propagated by the same means. And should we not then enjoy the same liberty, and be protected by the same laws.—

He finds slavery “incredible” in a nation founded on liberty and fair treatment.

It seems almost incredible that the advocates of liberty, should conceive the idea of selling a fellow creature to slavery…O miserable race, born to the same hopes, created with the same feeling, and destined for the same goal, you are reduced by your fellow creatures below the brute. The dog is protected and pampered at the board of his master, while the poor African and his descendant, where a Saint or a felon, is branded with infamy, registered as a slave, and we may expect shortly to find a law to prevent their increase, by taxing them according to numbers, and authorizing the Constables to seize and confine everyone who dare to walk the streets without a collar on his neck—what have the people of colour been guilty of, that they more than others, should be compelled to register their houses, lands, servants and children.

He hopes that the legislature will be guided by humanity and mercy to correct the suffering of all blacks.

It is to be hoped that in our legislature there is a patriotism, humanity, and mercy sufficient to crush this attempt upon the civil liberty of freemen, and to prove that the enlightened body who have hitherto guarded their fellow creatures, without regard to the colour of the skin, will stretch forth the wings of protection to that race, whose persons have been the scorn, and whose calamities have been the jest of the world for ages. We trust the time is at hand when this obnoxious bill will receive its death warrant, and freedom still remain to cheer the bosom of a man of colour.

Passing the exclusion bill before congress will only increase the sense of degradation that already exists.

Are not men of colour sufficiently degraded? Why then increase their degradation…If men, though they know that the law protects all, will dare, in defiance of law, to execute their hatred upon the defenseless black, will they not by the passage of this bill, believe him still more a mark for their venom and spleen—Will they not believe him completely deserted by authority, and subject to every outrage brutality can inflict —too surely they will, and the poor wretch will turn his eyes around to look in vain for protection.

For the sake of humanity, won’t the white rulers become advocates for blacks rather than add to their despair.

Pause, ye rulers of a free people, before you give us over to despair and violation—we implore you, for the sake of humanity, to snatch us from the pinnacle of ruin, from that gulf, which will swallow our rights, as fellow creatures; our privileges, as citizens; and our liberties, as men!

I have done. My feelings are acute, and I have ventured to express them without intending either accusation or insult to anyone. An appeal to the heart is my intention, and if I have failed, it is my great misfortune, not to have laid a power of eloquence sufficient to convince. But I trust the eloquence of nature will succeed, and the law-givers of this happy Commonwealth will yet remain the Black’s friend, and the advocates of Freemen, is the sincere wish of every freeman.

James Forten continues his efforts to prove that blacks can thrive in white society if only given a fair chance. He joins ministers Jones and Allen in supporting The Free African Society, and spends a large share of his fortune paying owners to free their slaves. Before his death in 1842, he also helps the white abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison, publish his Liberator newspaper, and participates in the underground railroad movement to transport run-away slaves to Canada.

In 1833 his wife Charlotte helps found a Female Anti-Slavery Society chapter in Philadelphia, and his legacy as a black abolitionist is carried on by his three daughters.

1816

Indiana’s Black Codes Follow Ohio’s Precedents

When the time comes for Indiana’s application for admittance, it follows a long history of attempting to allow slavery within its borders.

The territory is officially organized on July 4, 1800, with frontier fighter, William Henry Harrison, serving as first Governor from 1800-1812. Harrison grows up on Berkeley Plantation in Virginia, surrounded by slaves. Despite early brushes with Dr. Benjamin Rush and Quaker abolitionists, he concludes as Governor that Indiana would be more economically attractive to settlers were slavery allowed.

In turn, from 1803 onward, he attempts to skirt the sanctions imposed by the 1787 Northwest Ordinance — and white settlers from the South begin to filter into Indiana with slaves in tow.

Harrison touts this fait d’accompli to federal politicians, including Jefferson (who opposes it), but still fails to change the 1787 law. His next ploy is to recast all of the Indiana slaves as “indentured servants, serving terms of 90+ years.”

What follows is an open battle between white factions in the state that will be replicated over the next sixty years as America move west. On one side are southern slave owners who insist on the “right” to bring their “property” with them as they settle. On the other are northern whites, unlike Harrison, who want absolutely nothing to do with any blacks – slave or free – within their state.

The level of anti-black vitriol among the latter group is evident in “petitions” they address to the provisional state legislature at the time:

Your Petitioners also humbly pray that if your hournable boddy think propper to allow a donation of land to Setlers, People of Color and Slaveholder may be debarred from the lands so appropriated.

We are opposed to the introduction of slaves or free Negroes in any shape…Our corn houses, kitchens,’ smoke houses…may no doubt be robbed and our wives, children and daughters may and no doubt will be insulted and abused by those Africans. We do not wish to be saddled with them in any way.

As usual, the Africans are caught in the middle between those whites who wish to treat them as cattle and those who hope they will disappear completely.

By 1810 the population of the Indiana Territory is approaching “admission to statehood” levels, with 23,890 whites counted and 630 blacks – 237 recorded as slaves, 393 as freed.

This leads to a battle over writing a Constitution that includes a direct reference to the “black issues.”

With William Henry Harrison off to fight the War of 1812, the thought of converting Indiana into a slave-welcoming state vanishes, and popular interest shifts to a “cleansing” solution.

In the end, Indiana follows suit with Ohio in its 1816 black codes. These require that all blacks must be able to “show their papers” on demand. For example:

I, Andre Lewis, clerk of the Gibson Circuit Court, hereby certify that Lilly Ann Perry, a negro age 28 years, with light complexion, born in the state of North Carolina, resides now in Gibson, Indiana..

They also include posting of the $500 bond to guarantee good behavior.

But then Indiana goes even further, piling other constraints on its free blacks – by barring rights to schooling, to testifying in court, to serving in the militia, and to voting.

December 10, 1815

The Black Abolitionist Paul Cuffee Explores The Option Of Repatriation

From the inception of slavery in America, heroic black activists have sought ways to put an end to it.

One of the first is Paul Cuffee.

Cuffee is born in 1759 on Cuttyhunk Island off the coast of Massachusetts. His mother is Native American and his father an African, granted freedom by his Quaker owner. Their values and industriousness shape Cuffee, and prepare him to achieve two lifetime goals: starting up a successful shipping business and reuniting black slaves with their African roots.

His life at sea begins as deckhand on a whaler, shifts to running a cargo boat around Nantucket, and builds over time to ownership of several international merchant ships that make him a rich man, living on the waterfront in Westport, Massachusetts.

With his newfound wealth, he turns toward restoring freedom and dignity to America’s slaves.

His travels abroad connect him with freed men in Britain attempting to transport blacks to a new home in Sierra Leone. This crown colony on the west coast of Africa, is first established by the “Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor” in 1787.

In 1810 Cuffee sails to Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, to assess progress among the early settlers. He then returns to the U.S. to gather financial support for his own initial transport.

On December 10, 1815, he sets off for a return trip with 38 freed slaves in tow.

With proof of early successes in hand, Cuffee petitions Congress in 1816 for funds to greatly expand the Sierra Leone project, but is turned down.

He continues to search for financial support into 1817, when his health deteriorates and he dies, leaving behind an estate valued at $20,000 (roughly $4 million in today’s dollars).

What refuses, however, to die with Cuffee are two things: the black man’s interest in finding his freedom and roots in Africa and the white man’s interest in repatriation as a path to solving the slavery issue.

December 21, 1816

Whites Proposes A “Colonization” Answer

On December 21, 1816, a group of prominent whites back east gather in Washington to form “The Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America.” The founders include:

- Reverend Robert Finley, a renowned educator and Presbyterian minister, who initiates the idea.

- Speaker of the House, Henry Clay, of Kentucky.

- John Randolph, a Virginia planter and member of the House.

- Richard Lee, Virginia planter, brother of General Harry Lee (whose son is Robert E. Lee).

- Charles Mercer, a Federalist lawyer and member of the Virginia Assembly.

Motivations behind this “American Colonization Society” vary widely.

Some appear to be well intentioned, viewing repatriation as the best hope for gradually ending slavery and giving those freed a decent life back home.

Most, however, are driven by fear and prejudice. An address to the opening session of the ACS sums this up as follows:

We say in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal and have certain unalienable rights.” Yet it is considered impossible, consistent with the safety of the State, and it is certainly impossible with the present feeling towards these people, that they can ever be placed upon this equality…while they remain mixed with us. Some persons may call it prejudice. No matter! Prejudice is as powerful a motive, and will certainly exclude them, as the soundest reason.

This latter faction see colonization as a way for Northerners to achieve the kind of racial “cleansing” being pursued in Ohio and Indiana, and for Southern plantation owners to remove “uppity slaves” who might cause uprisings.

The Society first explores a site in the Sierra Leone area already opened up by repatriation proponents in England — but it conclude that conditions there aren’t viable.

Instead it sends a ship in 1821 to a potential site at Cape Mesurado, just south of Sierra Leone. Once there the voyagers “buy” land from local tribesmen in exchange for trinkets and set up an outpost.

They name the outpost Liberia, and the capital Monrovia, in honor of James Monroe, a member of the Society.

January 15, 1817

Rev Allen And AME Church Oppose Colonization

On January 15, 1817, some three thousand free blacks pack into the Reverend Richard Allen’s African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia to debate and vote on the American Colonization Society’s repatriation plans.

Their decision provides a remarkable statement about what the assembly regards as justice for their race.

It begins by citing the vital role that slave labor played in building America and the injustice implied in denying blacks the right to enjoy the fruits of this labor through repatriation.

Whereas our ancestors (not of choice) were the first culttors of the wilds of America, we their descendents feel ourselves entitled to participate in the blessings of her luxuriant soil, which their blood and sweat manured; and that any measure…having a tendency to banish us from her bosom would not only be cruel, but in direct violation of those principles, which has been the boast of the republic.

It then resolves to remain in America, to keep faith with other blacks still enslaved, and to support efforts to gain their freedom.

It is resolved that we never will separate ourselves voluntarily from the slave population in this country; they are our brethren by the ties of consanguinity, of suffering, and of wrongs; and we feel that there is more virtue in suffering privations with them, than fancied advantages for a season.

This outcome represents one more turning point on behalf of black emancipation and assimilation.

Despite this, the American Colonization Society will go forward with its plans. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the ACS will transport some 16,000 blacks to the colony of Liberia — and in 1847 it will be declared an independent republic.

But the scheme sputters as white proponents find that costs are simply prohibitive – first to purchase the slaves from their owners and then to transport them back across the ocean.

Opposition from free blacks like James Forten, Richard Allen and their followers also eliminates the possibility of using colonization to “cleanse” their cities and frontiers of all people of color.

What remains then for Northern whites who want nothing to do with blacks is to pass ever more burdensome local statutes to discourage new residents and to segregate and punish those already in their midst.