Section #2 - A new Constitution is adopted and government operations start up

Chapter 18: Washington’s Second Term

1790

Pro-Administration Forces Win The First Mid-Term Elections

According to the 1787 Constitution, elections for membership in the House of Representatives are to be held every two years – or “mid-term” in the sitting President’s time in office.

America’s first such election begins on March 4, 1791 in Vermont and ends on June 1, 1792 in Kentucky – two states which have been recently admitted to the Union. Each has been allocated a pair of seats based on their populations, and this raises the total number in the chamber from 65 to 69.

The results again demonstrate that, despite George Washington’s overwhelming personal popularity, the pro-administration forces enjoy only a narrow 39-30 majority in the House.

House Of Representatives Mid-Term Election Of 1790

| Total # Seats | Pro-Admin | Anti-Admin | |

| 1788 | 65 | 37 | 28 |

| 1790 | 69 | 39 | 30 |

| Change | +4 | +2 | +2 |

Opposition to the administration centers mainly across the South, where many voters regard Washington as tilting toward the Federalists and Hamilton and away from their leader, Jefferson.

House Of Representatives Election Of 1790

| 1788 Election | Total | South | Border | North |

| Pro-Administration | 37 | 7 | 3 | 27 |

| Anti-Administration | 28 | 16 | 4 | 8 |

| 1790 Election | ||||

| Pro -Administration | 39 | 7 | 4 | 28 |

| Anti-Administration | 30 | 16 | 5 | 9 |

Anti-Administration sentiment is strongest in Virginia, while support for the President’s policies is greatest in Massachusetts, Connecticut and New Jersey.

House Of Representatives Election Of 1790

| South | # Seats | Pro Admin | Anti Admin |

| Virginia | 10 | 2 | 8 +1 |

| North Carolina | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| South Carolina | 5 | 3 +1 | 2 |

| Georgia | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| South | 23 | 7 | 16 |

| Delaware | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Maryland | 6 | 3 +1 | 3 |

| Kentucky | 2 | 0 | 2 +2 |

| Border | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| New Hampshire | 3 | 3 +1 | 0 |

| Massachusetts | 8 | 7 +1 | 1 |

| Rhode Island | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Connecticut | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| New York | 6 | 4 +1 | 2 |

| New Jersey | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Pennsylvania | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Vermont | 2 | 0 | 2 +2 |

| North | 37 | 28 | 9 |

| Total | 69 | 39 | 30 |

Control in the Senate remains with the Pro-Administration by a margin of 18-11.

November 2 to December 5, 1792

The Presidential Election Of 1792

Reactions to the revolutionary events in France are on the minds of Americans as they go to the polls in 1792.

The Federalist leaders – especially Hamilton and Adams – applaud the move away from absolute monarchy, but are distressed by the Reign of Terror. They view the riots in Paris and violence against the nobility, as what happens when democracy turns into mob rule. They are also very alarmed by France’s declaration of war on its European neighbors, and fear that it might spill over to America.

Meanwhile, Jefferson and the Anti-Federalists, now referred to as Democratic-Republicans, are much more comfortable with the “will of the people” being carried out on the streets of France and in mass assemblies. They are forever suspicious of British intentions toward America, and regard the French as more certain allies.

Still the election of 1792 focuses much more on domestic policies than on foreign affairs. Hamilton’s economic initiatives – the assumption of state debts, the tariff and excise taxes, capitalism, and the U.S. Bank – have exacerbated the on-going rift between the Federalists and their opponents. So the election of 1792 is the first to be openly fought over by “political parties.”

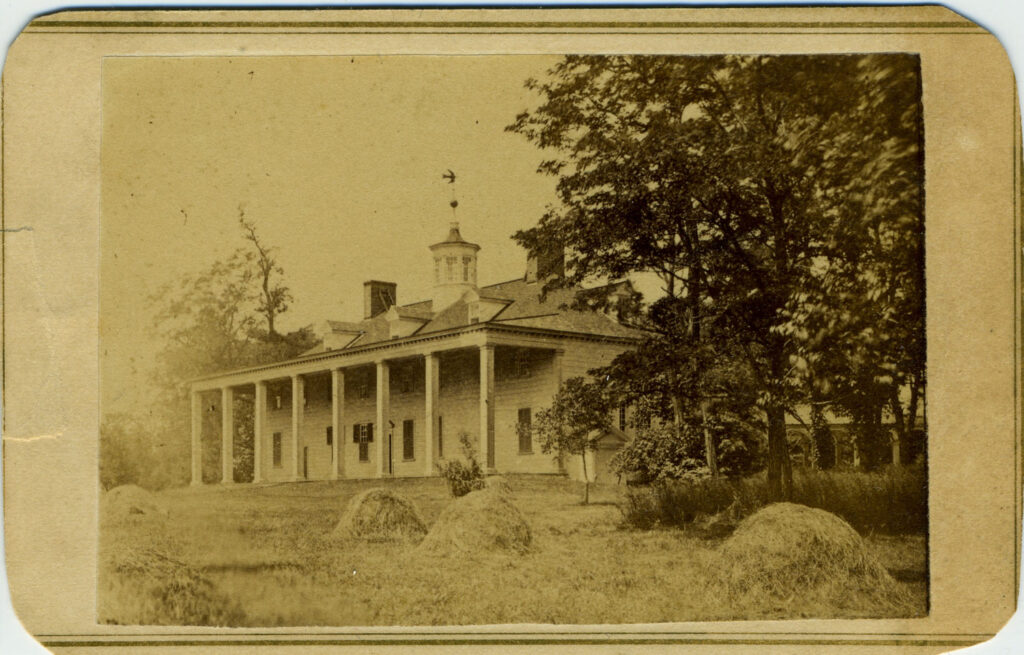

Madison in particular senses threats here to national unity, and he persuades Washington to accept a second term rather than retire to Mt. Vernon, which is his stated preference. Some worry that this will lead on to monarchy, but the fact that Washington is without children quells this fear.

Since all sides share confidence in Washington, the political battle is about “who will be Vice-President?” The Federalist prefer John Adams of Massachusetts; the Democratic-Republicans offer Governor George Clinton of New York, one who lobbied aggressively against ratifying the 1787 Constitution.

The voting process itself is unchanged from 1788. Each State has a number of “presidential electors” equal to their representation in the House. Roughly half of the states choose “electors” by popular voting; the other half relies on votes by state legislators. Each elector names his top two choices for President. The candidate with the most votes will become President as long as he surpasses half of the total ballots cast; the runner-up will become Vice-President.

Fifteen states participate, but only 28,579 citizens – less than 1% of the 4 million+ population – cast their own votes for the Executive in 1792. Over time this turn-out will grow substantially, as suffrage rules become more inclusive and political party divisions intensify public interest in the presidential outcomes.

In 1792, however, George Washington is again named on every elector’s ballot, and wins a second term in office.

The race for Vice-President is fairly close, with John Adams getting 77 votes to Clinton’s 50 votes.

Results Of The 1792 Presidential Election

| Candidates | State | Party | Pop Vote | Tot EV | South | Border | North |

| George Washington | Virginia | Independent | 28,579 | 132 | 45 | 15 | 72 |

| John Adams | Mass | Federalist | 77 | ||||

| George Clinton | New York | Dem-Rep | 50 | ||||

| Thomas Jefferson | Virginia | Dem-Rep | 4 | ||||

| Aaron Burr | New York | Dem-Rep | 1 | ||||

| Total | 28,579 | 264 | |||||

| Needed To Win | 67 |

1792

The Democratic-Republicans Gain Seats In Congress

The nation’s first “reapportioment” of Congressional seats occurs after the national Census of 1790. Based on the results, the House of Representatives adds 36 new seats in 1992, with 20 of these coming in the Northern states.

House Of Representatives – Post 1790 Census Seat Adjustments

| Total | South | Border | North | |

| 1790 | 69 | 23 | 9 | 37 |

| 1792 | 105 | 37 | 11 | 57 |

| Change | +36 | +14 | +2 | +20 |

When the votes are in, the majority in the House has shifted from a 39-30 margin for the Pro-Administration Federalist faction to a 55-50 edge for the Democratic-Republicans.

House Of Representatives Election Trends

| # Seats | Pro-Admin | Anti-Admin | |

| 1789 | 65 | 37 | 28 |

| 1791 | 69 | 39 | 30 |

| 1793 | 105 | 50 | 55 |

The Democratic-Republicans pick up ground in Pennsylvania and Vermont, as well as expanding their control of the South – while the stronghold for the Federalists continues to lie in the Northern states.

House Trends By Region

| Pro-Administration | Total | South | Border | North |

| 1789 | 37 | 7 | 3 | 27 |

| 1791 | 39 | 7 | 4 | 28 |

| 1793 | 50 | 6 | 4 | 40 |

| Anti-Administration | Total | South | Border | North |

| 1789 | 28 | 16 | 4 | 8 |

| 1791 | 30 | 16 | 5 | 9 |

| 1793 | 55 | 31 | 7 | 17 |

In the Senate, the “staggered cycles” approach has a total of 10 seats up for election in 1792. The same patterns seen in the House are evident in the upper chamber – with the Anti-Federalist opposition strengthening year after year, particularly in the South.

Senate Trends By Region

| Pro-Administration | Total | South | Border | North |

| 1789 | 19 | 4 | 3 | 12 |

| 1791 | 17 | 3 | 4 | 10 |

| 1793 | 16 | 1 | 4 | 11 |

| Anti-Administration | Total | South | Border | North |

| 1789 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 1791 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| 1793 | 14 | 7 | 2 | 5 |

March 4, 1793 – March 4, 1797

Overview Of Washington’s Second Term

When the time comes for Washington’s second inaugural, on March 4, 1793, the U.S. capital has moved from New York City to Philadelphia, where it remains until “Washington City” is completed in 1800.

Stability is a key virtue with the President, and his Cabinet remains intact as his new term begins. This will not, however, last long, as Jefferson will resign in 1793 over a foreign policy dispute, and Hamilton will exit in 1795 after his enemies expose an extra-marital affair.

Washington’s Cabinet: As Second Term Begins

| Position | Name | Home State |

| Vice-President | John Adams | Massachusetts |

| Secretary of State | Thomas Jefferson | Virginia |

| Secretary of Treasury | Alexander Hamilton | New York |

| Secretary of War | Henry Knox | Massachusetts |

| Attorney General | Edmund Randolph | Virginia |

The challenges facing Washington in 1793 are fundamentally different from 1789. The basic structure and daily functions of the federal government are now fairly well established – so the focus shifts to executing the domestic programs set by the Federalists, and participating in foreign affairs.

In foreign policy, his second term will be marked by the “Amity Treaty” and other efforts to remain neutral in the face of renewed warfare involving Britain and France. In October 1795 the Pinckney Treaty with Spain settles U.S. boundary lines – west to the Mississippi River and south to the 31st parallel, the northern line of Spanish Florida.

Domestically, he will sign the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, and use force to help settlers combat Indian tribes west of the Appalachians and to put down a tax revolt in Pennsylvania known as the Whiskey Rebellion. His 1795 Naturalization Act requires that future immigrants reside for five years in America before achieving citizenship.

In regard to the economy, recent “ballpark estimates” of activity during Washington’s tenure suggest that America’s prosperity – derailed during the Revolutionary War – has been restored by 1793 or so, under Hamilton’s leadership.

Economic Growth During Washington’s Terms

| 1790 | 1791 | 1792 | 1793 | 1794 | 1795 | 1796 | |

| Total GDP ($MM) | $189 | 206 | 225 | 251 | 315 | 383 | 417 |

| Per Capita GDP | $ 48 | 51 | 54 | 58 | 71 | 84 | 89 |

| % Change | 6% | 6% | 7% | 22% | 18% | 6% |

While his many supporters urge him to continue with a third term, Washington demurs.

The new nation he helped to found is up and running, at peace and with the strong central government he wanted in place.

As Washington exits, he will pen a memorable farewell to America, summarizing his learning as President and his advice to his successors.

Washington’s Second Term: Key Events

| 1793 | |

| March 4 | Washington and Adams are sworn in |

| April 8 | “Citizen Genet” arrives in Charleston and begins to foment anti-British feelings |

| April 22 | Washington issues proclamation of neutrality in France vs. Britain war |

| May 9 | French declare they will seize ships bearing cargo to Britain |

| June 5 | Jefferson warns Genet against further mischief; Genet ignores the message. |

| November 6 | Britain begins to seize neutral ships and impress sailors to fight the war |

| December 31 | Jefferson resigns as Sec. of State over belief that US is tilting toward Britain |

| 1794 | |

| March 22 | Congress bans slave trading with foreign nations |

| March 27 | Congress authorizes establishment of the US Navy |

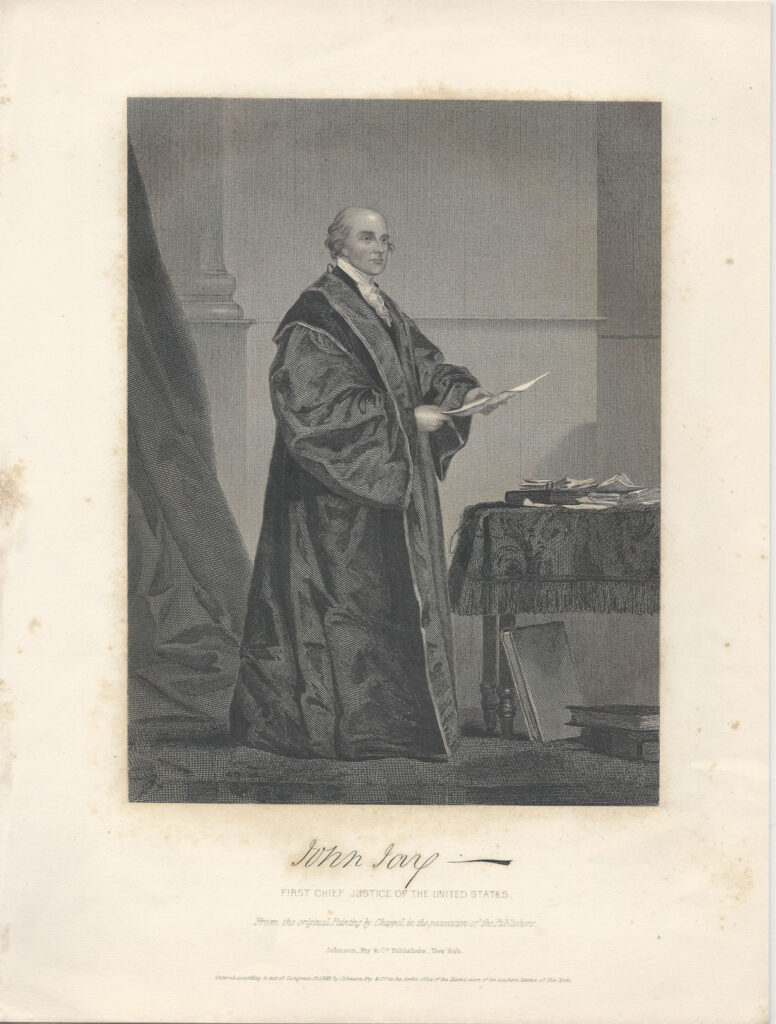

| April 19 | Chief Justice John Jay appointed Ambassador to Britain |

| May 1 | America’s first labor union (“Cordwainers/shoemakers) begins |

| May 27 | James Monroe appointed Minister to France |

| June 5 | Congress passes The Neutrality Act |

| August 7 | Washington assembles 13,000 man militia to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion |

| August 20 | Rebellious Miami tribe defeated near Toledo by “Mad” Anthony Wayne |

| November 19 | John Jay concludes an “Amity Treaty” with Britain |

| December | The 61 mile Lancaster Turnpike (road) is completed |

| 1795 | |

| January 29 | Naturalization Act requires a 5 year residency prior to citizenship |

| January 31 | Hamilton resigns as Treasury Secretary amidst marital scandal |

| June 24 | Jay’s “Amity Treaty” is finally approved by the Senate |

| July 19 | The Connecticut Land Company buys the large Western Reserve tract in Ohio |

| August 3 | The Treaty of Greenville cedes large Ohio tribe land tracts to the US |

| October 27 | Treaty of Lorenzo with Spain defines land boundaries in the US southeast |

| December 15 | The Senate rejects John Rutledge, Washington’s choice as Chief Justice |

| 1796 | |

| February 29 | The Amity Treat with Britain is announced publicly and France is outraged |

| March 4 | The Senate confirms Oliver Ellsworth is as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court |

| March 8 | In Hylton v United States the Supreme Courts rules its first law unconstitutional |

| April 30 | Democratic-Republicans criticize funding of Amity Act provisions, which pass |

| May 18 | Land Act opens up more NW Territory Land at $2 per acre, 640 acre minimum |

| June 1 | Tennessee is admitted to the Union (#16) |

| July | France announces it will board all ships bound for Britain, even neutrals |

| August 22 | French refuse to accept Thomas Pinckney as new Ambassador, given grievances |

| September 19 | Washington’s Farewell Address to the nation is published; signals no third term |

| October 29 | First US ship reaches California, at Monterrey Bay |

| November 4 | US signs treaty with Tripoli to end pirating raids on commercial ships |

| November | Andrew Jackson becomes Tennessee’s first member of the US House |

| December 7 | John Adams is elected as the second US President, with Jefferson as VP |

| 1797 | |

| February 27 | Sec of State Pickering reports losses from France’s prohibitions of trade |

March 4, 1793

Sidebar: Washington’s Second Inaugural Address

The President lives up to his reputation for brevity on March 4, 1793, with the shortest inaugural address in American history – 135 words in length delivered in under two minutes of time.

I am again called upon by the voice of my country to execute the functions of its Chief Magistrate When the occasion proper for it shall arrive, I shall endeavor to express the high sense I entertain of this distinguished honor, and of the confidence which has been reposed in me by the people of united America.

Previous to the execution of any official act of the President the Constitution requires an oath of office. This oath I am now about to take, and in your presence: That if it shall be found during my administration the Government I have in any instance violated willingly or knowingly the injunctions thereof, I may (besides incurring constitutional punishment) be subject to the upbraidings of all who are now witnesses of the present solemn ceremony.

Summer 1794

A Show Of Federal Force Puts Down The Whiskey Tax Rebellion

As Washington is busy navigating foreign policy, he faces a domestic revolt over taxes.

The first levy imposed by the new Congress on American products targets whiskey and goes into effect on March 3, 1791. It is met by stiff resistance from grain farmers, whose backyard “stills” provide a lucrative source of secondary income.

The economics here are simple. Earn $6 in profit by loading 24 bushels of milled rye on three-pack mules and sending them east over the Alleghenies, or earn $16 by shipping two eight-gallon kegs of whiskey on one mule.

For many small farmers this income means the difference between surviving the lingering post-war recession or going under and losing their land to banks or wealthy speculators.

Given these realities, they ask why the government has decided to penalize whiskey production in the first place, and why the burden falls disproportionately on small farms, which run their stills below the “rated maximum” output level which determines the tax.

Western Pennsylvania, with a quarter of all the “stills” in the country, quickly becomes a rallying point for open rebellion against local tax collectors.

The first victim is one Robert Johnson, who is “tarred and feathered” in September 1791 by a band of anti-tax men, while making his rounds. More attacks follow, and in August 1792 the Mingo Creek Association is formed to consolidate resistance in southwestern Pennsylvania and beyond. Some 500 men sign on to the cause.

The threat continues to escalate over the next two years, with more violence against tax collectors, talk of seizing and “re-distributing” land from wealthy property owners, and even the possibility of turning to Spain for help.

Two Anti-Federalist congressmen from Pennsylvania, Albert Gallatin and William Findlay, petition Hamilton to change the law. Gallatin, later Secretary of the Treasury under Jefferson, writes:

We have punctually and cheerfully paid former taxes on our estates…because they were proportioned to our wealth…we believe this (tax) to be founded on no such equitable principles…we respectfully apply for a total repeal of the law.

Hamilton, who needs the money for his budget, will have none of this.

On July 16, 1794, the protests turn into the “Whiskey Rebellion,” as a 500 man mob assaults the home of Revolutionary War General John Neville, a wealthy farmer and distiller also serving as the local Inspector of Revenue. Neville fights off the attack with the help of his slaves and 10 regular army soldiers from the federal fort in Pittsburgh. Two rebels and one soldier are killed in the battle.

In August a gathering of 7,000 near Pittsburg hear a rebel named David Bradford, citing the French Revolution, and calling for a redistribution of wealth and independence from the oppressive union.

President Washington knows treason when he sees it and nationalizes state militias from Pennsylvania, Virginia, New Jersey and Maryland. A total of 13,000 troops, more than participated at Yorktown, march off to suppress the rebels. The old General himself leads the troops into Pennsylvania before turning the lead over to Hamilton and “Lighthorse Harry Lee.”

But this overwhelming show of force is enough to shatter the rebellion. The leaders disperse into the mountains, although 20 of them are captured and sent back to Philadelphia for trial. They prove to be a woeful band, and only two are convicted – then pardoned.

In 1802 the hated Whiskey Tax bill is repealed by the staunch Anti-Federalist, Jefferson.

June 24, 1795

Washington is at Mt. Vernon in February 1793 when he learns that Robespierre’s France has declared war on Britain. He quickly returns to Philadelphia and an emergency meeting where he poses 13 questions to his Cabinet members. These range from the tactical – “whether to receive a new French ambassador” – to the strategic – “whether to issue a proclamation of neutrality.”

All agree that America must avoid direct involvement in a British-French conflict, but a rift develops around how quickly and aggressively to signal this policy. Secretary of State Jefferson, forever siding with France, argues for withholding any official proclamation, at least for the time being. Treasury Secretary Hamilton, perpetually pro-British, disagrees vehemently.

This leaves the final call up to Washington, who supports Hamilton, and issues a Proclamation of Neutrality on April 22, 1793.

Whereas it appears that a state of war exists between Austria, Prussia, Sardinia, Great Britain, and the Netherlands of the one part and France on the other, and the duty and interest of the United States require that they should with sincerity and good faith adopt and pursue a conduct friendly and impartial toward the belligerent powers.

The President soon learns, however, that two weeks before the Neutrality decree, the new ambassador from France, “Citizen” Edmund-Charles Genet, has landed at Charleston, South Carolina, and begun to recruit a local militia to attack Spanish Florida. When later asked by Washington to desist, Genet responds by sending his privateer navy to raid British transports along the Atlantic coast. Genet’s stunts undermine Jefferson’s pro-French arguments and embarrass him personally. On December 31, 1793, he resigns from the Cabinet.

Jefferson has threatened this action before on several occasions, only to be talked back on board by Washington. But this time the President lets him go. Jefferson expresses relief at the prospect of a return to Monticello.

Liberated from the hated occupations of politics and into the bosom of my family, my farm, and my books.

Federalist critics are suspicious of his real motives. As John Adams writes:

Jefferson thinks by this step to get the reputation as a humble, modest, meek man, wholly without ambition or vanity…But if the prospect opens, the world will see and he will feel that he is as ambitious as Oliver Cromwell.

Washington names Attorney General Edmund Randolph to the Secretary of State post, and moves to reassure the British by sending John Jay, the sitting Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, to London for bilateral talks.

This is just one more critical role for Jay in America’s path to independence. He serves as a delegate to both the First and Second Continental Congresses, Minister to Spain (1779-82), and Minister of Foreign Affairs (1784-1790) before joining the high court. He is also comfortable in politics, later becoming Governor of New York.

Jay arrives in London on June 8, 1794, and negotiates over the next five months with Foreign Secretary, Lord Grenville. Washington feels the results are fairly lackluster, but at least they dampen some ongoing tensions.

- Both sides agree to cease raiding the other’s ships and pay compensations for prior damages.

- The British will finally withdraw from border forts along the Detroit to Sandusky line, while any further border disputes will be resolved by a joint commission.

- Free trade will resume across America and the British Indies – including relief of restrictions on American exports and a continuation of England’s involvement in the fur industry.

- America will cover debts owed to British interests back to 1776.

Jay signs the treaty on November 21, 1794, and from there resistance to ratifying it gets underway.

Washington’s Minister to France, James Monroe, is left in the dark about the terms, and when he learns them his hostility toward Jay and the treaty boils over. Instead of acting the role of “diplomat,” Monroe sympathizes with the French, who argue that the Jay Treaty violates their 1788 Treaty with America. Monroe becomes so publicly outspoken on the matter that Washington fires him.

In addition to Monroe, many citizens are still smarting from the war with Britain, and recall that it was the alliance with France that actually led to victory. Both Jefferson and James Madison remain outraged. Still the Federalists muster enough support in Congress to finally approve it on June 24, 1795. It squeaks by the 2/3rds rule in the Senate on a 20-10 count, and barely secures funding in the House by a 51-48 margin.

The result is that America now has “Amity Treaties” with both France (the crucial 1778 accord) and Britain – although neither is particularly amicable at the moment.

That however suits Washington’s policy. If the two European powers wish to battle each other, so be it. America intends to remain neutral, while also trading freely with both partners.

August 3, 1795

American Forces Wrest Ohio From The Western Indian Confederacy

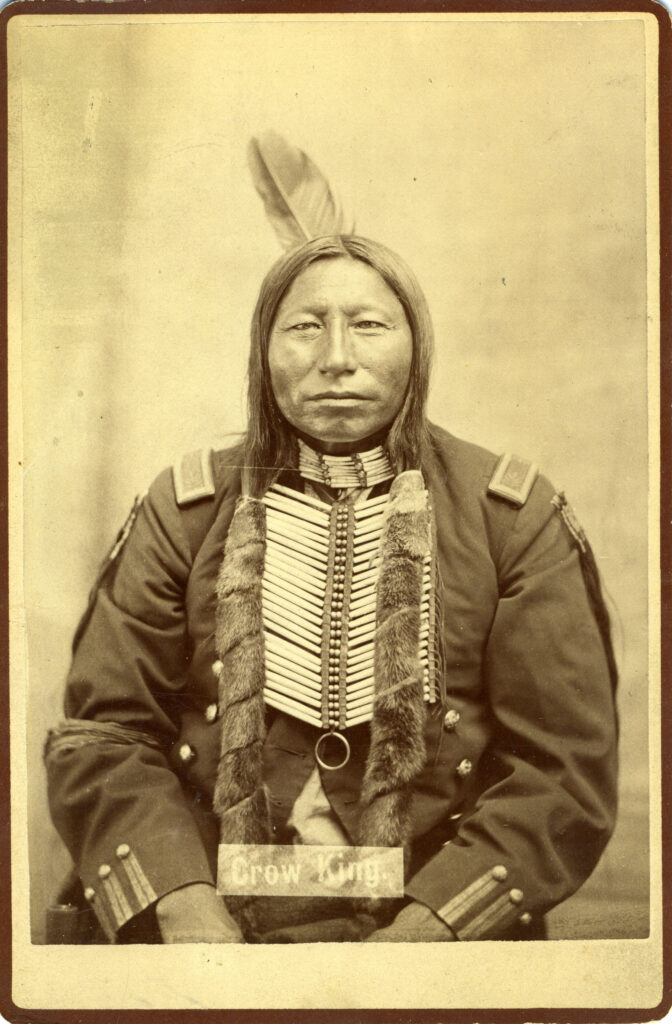

Crow King (died 1884)

During his second term, Washington is also forced to come to grips with failing U.S. policies toward the Indian tribes, especially regarding territorial disputes.

From the beginning, the white European settlers have treated the Native Americans in a much more cordial fashion than their black African slaves. In addition to their “aboriginal status” on the land, this is in large part because of the potential they offer as military allies in the international wars to control the continent. Their reputation as warriors is well established; their numbers are sizable; and their tactical knowledge of the geography and potential fields of battle and supply are unmatched. So they are courted.

In the French & Indian War of 1754-63, the dominant Algonquin tribes side with France, while the Iroquois back Britain. In the Revolutionary War of 1776-1781, almost all northern tribes fight alongside the British, while the five main southern tribes (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creeks, Choctaw and Seminoles) remain neutral.

It seems likely that this alignment with the redcoats in 1776 – and later in 1812 – contributes to growing ill will among America toward the Indians. But the stated policy toward them announced by the early presidents is nothing but conciliatory. Unlike the Africans, Indians are officially regarded as somehow akin to white men in their potential — “noble savages” to be “civilized” rather than subjugated.

Washington’s initial six-point plan to support this civilizing process includes a call for “impartial justice” toward the tribes, “regulated buying” of their land, punishment of those who violate their rights, and promotion of all efforts to support their commerce and their social advances. The stated hope here being that at least rudimentary assimilation into the American culture would come along with settled villages, property rights, English schooling, farming and exposure to Christianity.

But this rosy vision soon collapses as the tribes refuse to passively relinquish their historical homelands to white settlers crossing the Appalachian range onto “their territory.”

Open warfare over the land soon breaks out in the north and, on November 4, 1791, it is marked by a humiliating U.S. loss at the Battle of the Wabash, fought at Fort Recovery, on the western edge of Ohio. The Shawnee and Miami tribes—led by Blue Jacket and Little Turtle respectively—are pitted against a militia led by Arthur St. Clair, who was a major-general during the Revolutionary War.

The outcome is a rout, with some 600 soldiers killed, the worst defeat ever suffered by America’s military at the hands of tribal forces. Equally alarming is the rumor that Britain plays a role in the defeat by sending supplies to the Indians and encouraging them to fight.

When this tribal resistance continues into 1794, Washington finally calls upon one of his most trusted Generals from the Revolutionary War to come out of retirement and suppress the Indians.

General “Mad” Anthony Wayne is a Pennsylvania native, a practicing surveyor, and then a legislator in his home state before forming a militia unit in 1775. Fame finds him quickly. He joins Aaron Burr in the failed attack on Quebec City in 1776. He is with Washington at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777 and is a hero in the crucial victory at Monmouth in 1778. Promotions follow and he ends the war at Yorktown in 1781, afterwards being named a Major-General. He then negotiates peace treaties with the Creek and Cherokee tribes in Georgia, for which he is rewarded with a rice plantation, where he is living when Washington requests his help in Ohio.

“Mad” Anthony earns his nickname from his fiery temperament and his bold approach to combat. He quickly assembles and trains up 3,000 soldiers at a camp in far western Pennsylvania. He calls them the “Legion of the United States.”

Once they are ready, Wayne marches them some 200 miles north and west toward Maumee, Ohio, attacking various Indian outposts as he goes. On June 30, 1794, his troops are engaged by upwards of 2,000 tribesmen, but find safety at Fort Recovery, where St. Clair was beaten in 1791. General Wayne recovers from this set-back and advances, meeting the Indians on August 20, 1794, in the pivotal Battle of Fallen Timbers, near Toledo. With a two to one edge in manpower, Wayne defeats Blue Jacket and Little Turtle, thus stomping out tribal resistance in Ohio.

Wayne proceeds further west, occupying British forts along the way, and finishing up in Indiana, near what will become Ft. Wayne, subsequently named in his honor.

“Mad Anthony” has once again served Washington well, and the one-sided Treaty of Greenville, signed on August 3, 1795, officially ends the war in the north. It will not, however, be the last time that the native peoples of America are forced to forfeit their land to white men in rigged treaties.

September 19, 1796

Washington’s Farewell Address

Washington’s time of service to his nation now appears to be ending.

Before leaving for Mt. Vernon, he wants to share parting thoughts on securing the new nation he did so much to create. His farewell address is first published on September 19, 1796, six weeks in advance of the third presidential election.

The President begins by declaring that he will not run again, then goes on to thank the nation for the many honors he has received while in office. At this point he pauses…

Here, perhaps, I ought to stop. But solicitude for your welfare… urges me…to offer…some sentiments… which appear to me all important to the permanency of your felicity as a people. These will be offered to you…as the disinterested warnings of a parting friend…who can have no personal motive to bias his counsel.

He then charges forward with his advice to all citizens:

The unity of government which constitutes you one people is …now dear to you.

It is of infinite moment that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national union to your collective and individual happiness.

Think and speak of (your union) as of the palladium of your political safety and prosperity;

Discountenance… even a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned…frown upon…every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.

The name of American, which belongs to you… must always exalt the just pride of patriotism.

With slight shades of difference, you have the same religion, manners, habits and political principles. You have in a Common cause fought and triumphed together; the independence and liberty you possess are the work of joint counsels…common sufferings and successes.

The most commanding motives (exist) for carefully guarding and preserving the union of the whole… Protected by the equal laws of a common government…the North…the South…the East…the West…secure enjoyment of …outlets for their own production…across agriculture and manufacturing.

All the parts combined cannot fail to find in the united mass of means and efforts greater strength, greater resource, proportionably greater security from external danger – (along with) an exemption from…wars between themselves, which so frequently afflict countries not tied together by the same government.

(Union will) likewise…avoid the necessity of those overgrown military establishments which under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty.

To the efficacy and permanency of your Union, a government for the whole is indispensable. The basis of our political systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their constitutions of government…

(It is) the duty of every individual to obey the established government. All obstructions to the execution of the laws… are destructive of this fundamental principle, and of fatal tendency.

Beware) of cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men…subverting the power of the people and usurping for themselves the reins of government.

(Beware) of the danger of Parties in the State, with particular reference to the founding of them on geographical discriminations…The alternate domination of one faction over another, shaped by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension…is itself a frightful despotism….But it inclines the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute

power of an individual…and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction…turns this disposition to his own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.

A wise people (will) discourage and restrain…the spirit of party. It agitates the community with Ill founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door…to corruption.

(Preserve) the necessity of reciprocal checks in the exercise of political power, by dividing and distributing it into different depositories and constituting each the guardian of the public weal against invasions by others.

Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.

Promote institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge… (since) it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.

As a very important source of strength and security, cherish public credit. One method of preserving it is to use it as sparingly as possible.

Observe good faith and justice towards all nations; cultivate peace and harmony with all. In relation to the still subsisting war in Europe, my proclamation of the twenty-second of April, I793, is the index of my plan.

He then closes.

I fervently beseech the Almighty that, after forty five years of my life dedicated to its service with an upright zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will be consigned to oblivion, as myself must soon be to the mansions of rest.

Washington’s “sentiments” will ring down the corridors of time, as the nation he helped to found hurtles toward prosperity and then toward dissolution:

- Preserving the Union is sacrosanct to liberty, safety and prosperity.

- Frown upon any attempt to alienate any portion from the rest.

- It is the duty of all men to obey the laws they have created.

- Rely on distributed power and checks and balances to preserve liberty.

- Avoid an overgrown military establishment.

- Religion and morality are essential supports to good government.

- An informed and knowledgeable public is also essential.

- Public credit must be cherished and debt avoided to maintain strength.

- Cultivate peace and harmony towards all nations.

- Beware of political parties who seek domination and revenge.

In addition to his closing advice to his fellow countrymen, the “Farewell Address” also signals that Washington does not intend to run for a third term. This puts an end to early fears that the President would be transformed into a European-style monarch, once in office.

It foretells an orderly transition to a successor – even in the midst of threatening events abroad and no small degree of political tension at home.

The fate of the nation will rest on the laws and institutions that have been established between the 1787 Constitution and the first eight years of government of the people.

The United States of America will now survive without George Washington, the one man who has done more than any other, to set it in motion.

In 1797 the time has come for the still vigorous 65 year old General and President to lay down the burdens of public office and retire to his beloved Mt. Vernon estate. However, fatehas more in store for Washington.

1797-1799

Washington’s “Retirement” And Death At Mt. Vernon

When Washington arrives back home on March 15, 1797, he finds that the time and devotion he has put into the presidency has left Mt. Vernon in need of fundamental repairs, almost top to bottom. What follows is a daily influx of carpenters and painters and groundskeepers, all working long days to meet the master’s commands. But soon enough, his step-granddaughter, Nelly Custis, reports that:

Grampa is very well and much pleased with being once more Farmer Washington.

In retirement, Washington pursues his art collection, oversees his plantation and begins to worry about mortality and about the fact that he finds himself land rich, but cash poor. To cover his sizable living expenses he begins to aggressively sell off his large land holdings in the west.

He also finds himself being drawn back into the controversy surrounding what the Democratic Republicans argue was his favoritism for Britain over France. This has long been a cause celebre for men like Jefferson and Monroe, and Washington now encounters various pamphlets and messages he finds dismaying. He is particularly upset once again with Monroe, saying in a letter that he has exhibited a:

Mischievous and dangerous tendency, exposing to the public his private instructions and correspondence with his own government.

Dismay soon converts, however, into a level of open hostility toward the Anti-Federalists and the French that he had eschewed over his many years on the political stage. By December 1797 he is intent on stepping back into the arena to ward off the threat he sees from France.

I cannot remain an unconcerned spectator of the attempt of another power to accomplish (our downfall).

As France increases its hostile actions against the US, Adams decides to send a clear warning their way. Only July 2, 1798, he nominates Washington to return as a lieutenant general and commander-in-chief of all U.S. military forces. Washington accepts the post two days later and devotes much of his time over the next seventeen months preparing an army to defend against a French invasion. Along the way he also bickers with Adams over strategy and over his staff, especially his wish to name Hamilton, the President’s nemesis, as his top-ranked general.

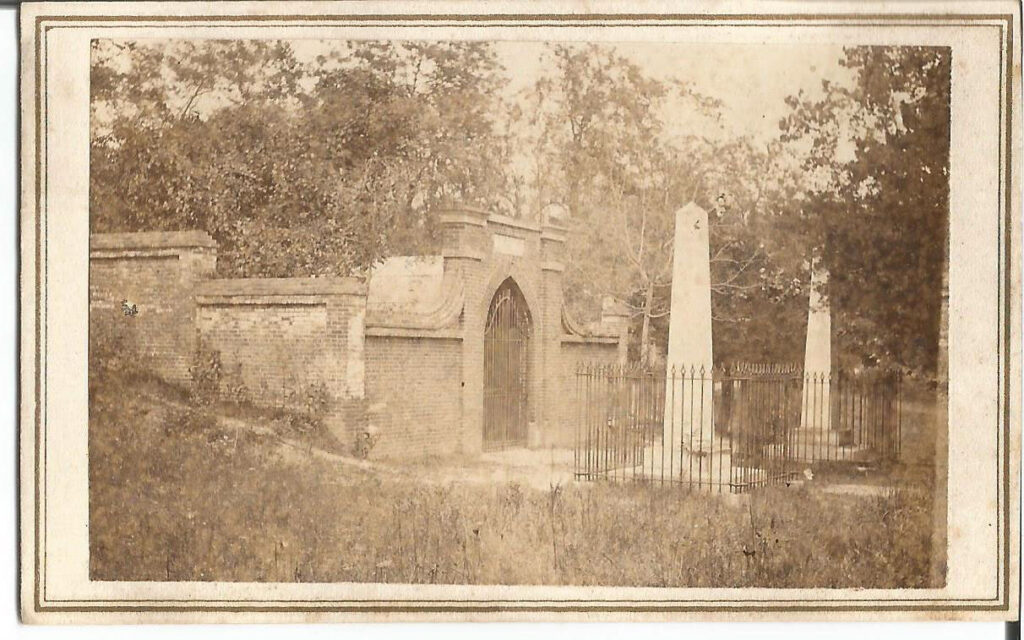

Washington is still serving his country when he dies suddenly at Mt. Vernon on December 14, 1799.

Two days earlier he records the following in his diary:

Morning cloudy. Winds to northeast and mercury 33. A large circle round the moon last night. At about ten o’clock it began to snow, soon after to hail, and then to a settled cold rain. Mercury 28 at night.

The storm he mentions starts soon after he rides out to inspect the far reaches of his farm. He returns home after five straight hours, soaking wet from the weather. He eats dinner and acknowledges that his throat is sore.

On December 13 he stays close to home and reads the daily newspaper with Martha and his aide before retiring. By 3am he awakens, feeling very ill, breathing heavily, and barely able to speak. He immediately senses that his life is in danger, and physicians are called. Before they arrive he tries, but is unable, to swallow a concoction of molasses, butter and vinegar. He then demands that bleeding should commence immediately, a common practice thought to rid the body of disease.

Three doctors finally arrive on December 14. More blood is drawn directly from Washington’s throat and from his arm. He remains unable to swallow liquids. The diagnosis they settle on is “quinsy,” a virulent form of tonsillitis, which calls for more bleeding and the application of blisters and purges. When nothing works, a trachea is debated to assist easier breathing, but it is rejected as too dangerous. One doctor finally insists that the bleeding stop, given the patient’s age and growing weakness – but the others disagree, and Washington is bled again, for a fourth time.

By afternoon, Washington knows he is about to die, and calls on Martha and his aide to make final arrangements. He burns one of two final wills and finally waives the doctors away when they try to continue the treatment. As night comes on, his mind turns to fear of being buried alive. He says to his aide:

I die hard, but I am not afraid to go….My breath cannot last long…Have me decently buried and do not let my body be put into the vault in less than three days after I am dead. Do you understand me?

With those words, the General passes. Elaborate memorials honoring Washington’s death will follow across the nation, but on December 19, a simple ceremony, organized by his local Masonic Lodge, carries him to a final resting place on his farm.

Of all the founding fathers, only Washington is unequivocal in his determination to eventually free all of his slaves. Fearing that a future executor might waver, he issues a military-like command:

I do hereby forbid the sale of any slave I may die possessed of, under any pretence whatsoever. See that this clause, respecting slaves, and every part thereof, be religiously fulfilled…without evasion, neglect or delay.

One year after Washington’s death in 1799, Martha declares their freedom, and also sets aside a fund to educate the slave children in preparation for their new life.