Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

Chapter 110: Two Powerful Black Abolitionists Make Their Voices Heard

Summer 1843

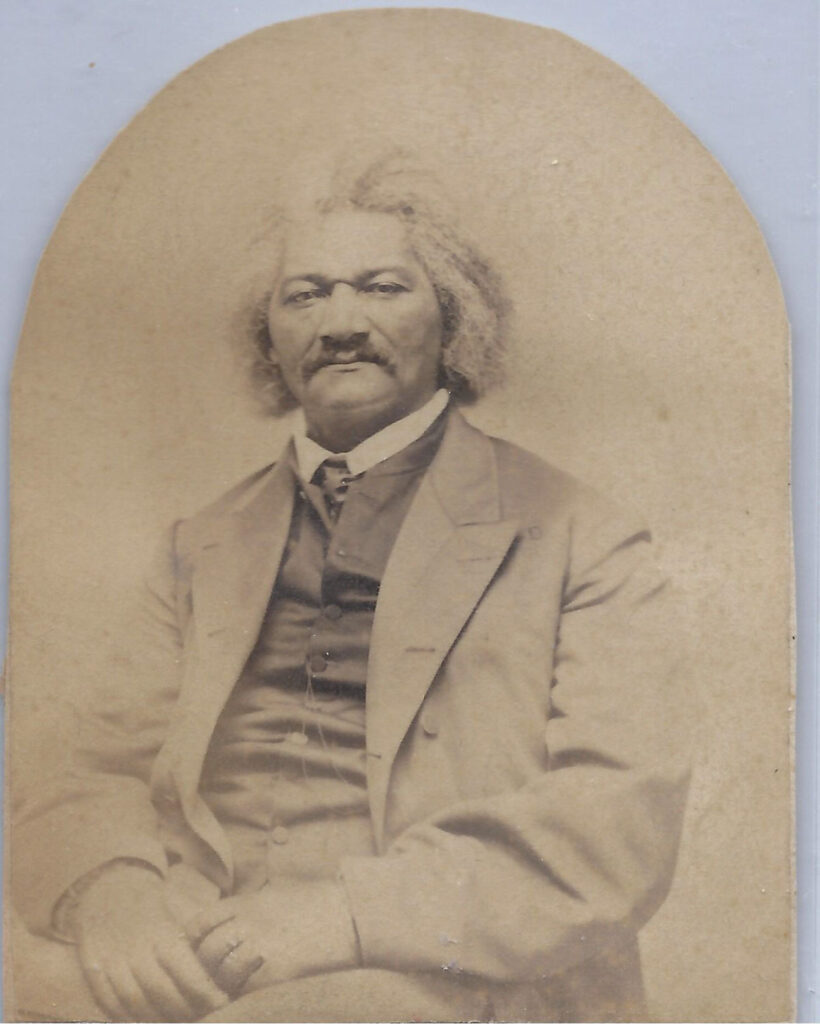

Frederick Douglass Becomes A National Spokesman For The Abolitionist Movement

On Nantucket in August 1841, the leader of the abolitionist cause, Lloyd Garrison, recognizes the powerful effect that Frederick Douglass could have on breaking through to white audiences about the evils of slavery.

It was at once deeply impressed upon my mind, that, if Mr. DOUGLASS could be persuaded to consecrate his time and talents to the promotion of the anti-slavery enterprise, a powerful impetus would be given to it, and a stunning blow at the same time inflicted on northern prejudice against a colored complexion

He invites Douglass to formally join the movement and Douglass accepts, immediately throwing himself into his destined mission.

In 1843 he joins the “One Hundred Conventions” tour at twenty-five as a lecturer. This is a grueling affair which takes him from upstate New York through Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana. Danger accompanies him at all stops. In Pendleton, Indiana, he is beaten by a white mob and ends up with a broken right hand that is never again fully functional.

Speaking mostly to white audiences, he recounts his own life experiences to establish his main themes:

- Blacks who are given a fair chance in America will, like himself, succeed and become good citizens.

- But slavery shuts off that opportunity by reducing Men to the status of Brutes.

- In the process of debasing blacks, whites commit atrocities that tarnish their immortal souls.

- They are often reinforced here by white churches that fail to live up to Christ’s teachings.

- The “slavery problem” can be solved if blacks are taught to read and write and given their freedom.

- Douglass himself is living proof of what is possible for America’s slave population.

The South quickly views the eloquent Frederick Douglass as a threat to their narrative about Africans as a separate species from whites, universally and irretrievably inferior, potentially violent, and best kept in captivity.

Douglass violates those stereotypes, as do other free blacks now intent on making themselves heard.

August 1843

Black Preacher Henry Highland Garnet Urges Slaves To Resist Their Oppressors

While Frederick Douglass is initially intent in 1843 on using moral persuasion to convince white masters to end slavery, the black preacher, Henry Highland Garnet is calling for physical resistance as the only option left.

Like Douglass, Garnet is a run-away slave, smuggled out of Maryland at nine years old, by his parents, George and Henrietta Trusty, who settle in New Hope, Pennsylvania before moving to New York City in 1824. Once there, the family name is changed from Trusty to Garnet, in order to throw off possible pursuers.

George finds work as a shoemaker and is able to enroll Henry in the African Free School when he is eleven. He soon falls in with a handful of other youths who will become leaders in the abolitionist movement: the future Episcopal minister, Alexander Crummel; college professor, Charles Reason; the MD, James McCune Smith. Together they found the Garrison Literary and Benevolent Society, in honor of the white reformer.

In 1829 slave-catchers in New York temporarily scatter Garnet’s family, and he ends working on a Long Island farm. He suffers a severe leg injury there while playing sports which leaves him on crutches and eventually ends with amputation. The disability turns him more inward, and soon both his studies and his church-going pick up. In 1835 he joins the First Colored Presbyterian Church and falls under the sway of the renowned Reverend Theodore Wright, co-founder of The American Anti-Slavery Society.

Later that year, Garnet attends an academy in New Hampshire run by the controversial utopian “perfectionist,” John Humphrey Noyes. After protestors destroy the schoolhouse, he moves to graduate from the Oneida Institute.

In 1840 he moves to Troy, NY, where he completes his education under the direction of Reverend Nathan Beman, one of Charles Finney’s “New School” converts. A year later he marries a Boston school teacher, begins preaching at his Liberty Street Presbyterian Church, and edits The National Watchman, a black themed newspaper.

Garnet’s fame as a preacher spreads, and in August, 1843, he is asked to address the National Negro Convention in Buffalo, an annual gathering of black leaders searching for ways to free their enslaved brethren. The speech he delivers sounds the same moral outrage and call to arms as David Walker’s 1829 “Appeal To Colored Citizens.”

He opens by declaring that prior attempts to end slavery have been in vain.

Brethren and Fellow Citizens:—Your brethren of the North, East, and West have been accustomed to meet together in National Conventions, to sympathize with each other, and to weep over your unhappy condition. …But, we have hoped in vain. Years have rolled on, and tens of thousands have been borne on streams of blood and tears, to the shores of eternity.

In particular the Christian Churches have stood idly by and watched.

…Two hundred and twenty seven years ago, the first of our injured race were brought to the shores of America. …The first dealings they had with men calling themselves Christians, exhibited to them the worst features of corrupt and sordid hearts; and convinced them that no cruelty is too great, no villainy and no robbery too abhorrent for even enlightened men to perform, when influenced by avarice and lust.

The bleeding captive plead his innocence, and pointed to Christianity who stood weeping at the cross. …But all was in vain. Slavery had stretched its dark wings of death over the land, the Church stood silently by, the priests prophesied falsely, and the people loved to have it so..

The colonists tried to blame slavery on Britain, but then embraced it on their own. The colonists threw the blame upon England. ..But time soon tested their sincerity.

In a few years the colonists grew strong, and severed themselves from the British Government…, did they emancipate the slaves? No; they rather added new links to our chains. ….

The time has come to recognize that God views it as sinful to continue submitting to this oppression.

…He who brings his fellow down so low, as to make him contented with a condition of slavery, commits the highest crime against God and man. Brethren, your oppressors aim to do this. They endeavor to make you as much like brutes as possible.

…TO SUCH DEGREDATION IT IS SINFUL IN THE EXTREME FOR YOU TO MAKE VOLUNTARY SUBMISSION….. Your condition does not absolve you from your moral obligation. The diabolical injustice by which your liberties are cloven down, NEITHER GOD, NOR ANGELS, OR JUST MEN, COMMAND YOU TO SUFFER FOR A SINGLE

MOMENT. THEREFORE IT IS YOUR SOLEMN AND IMPERATIVE DUTY TO USE EVERY MEANS, BOTH MORAL, INTELLECTUAL, AND PHYSICAL THAT PROMISES SUCCESS.

Brethren, it is as wrong for your lordly oppressors to keep you in slavery, as it was for the man thief to steal our ancestors from the coast of Africa. You should therefore now use the same manner of resistance, as would have been just in our ancestors when the bloody foot prints of the first remorseless soul thief was placed upon the shores of our fatherland.

In turn, the time has come for the slaves to “strike the blow” for themselves!

Brethren, the time has come when you must act for yourselves. It is an old and true saying that, “if hereditary bondmen would be free, they must them¬selves strike the blow.” You can plead your own cause, and do the work of emancipation better than any others.

…The combined powers of Europe have placed their broad seal of disapprobation upon the African slave trade. But in the slave¬holding parts of the United States, the trade is as brisk as ever. They buy and sell you as though you were brute beasts. …Look around you, and behold the bosoms of your loving wives heaving with untold agonies! Hear the cries of your poor children! Remember the stripes your fathers bore. Think of the torture

and disgrace of your noble mothers. Think of your wretched sisters, loving virtue and purity, as they are driven into concubinage and are exposed to the unbridled lusts of incarnate devils.

It is better to “die freemen than live to be slaves.”

…Then go to your lordly en¬slavers and tell them plainly, that you are determined to be free. Appeal to their sense of justice, and tell them that they have no more right to oppress you, than you have to enslave them… If they then commence the work of death, they, and not you, will be responsible for the consequences. You had better all die immediately, than live slaves and entail your wretchedness upon your posterity. If you would be free in this generation, here is your only hope. However much you and all of us may desire it, there is not much hope of redemption without the shedding of blood. If you must bleed, let it all come at once—rather die freemen, than live to be slaves.

Escape is impossible – with Garnet presciently citing free Mexico as an expansionist target for the South.

It is impossible like the children of Israel, to make a grand exodus from the land of bondage. The Pharaohs are on both sides of the blood red waters! You cannot move en masse, to the dominions of the British Queen—nor can you pass through Florida and overrun Texas, and at last find peace in Mexico. The propagators of American slavery are spending their blood and treasure, that they may plant the black flag in the heart of Mexico and riot in the halls of the Montezumas.

Fellow men! Patient sufferers! behold your dearest rights crushed to the earth! See your sons murdered, and your wives, mothers and sisters doomed to prostitution. In the name of the merciful God, and by all that life is worth, let it no longer be a debatable question whether it is better to choose Liberty or death.

Then comes a litany of heroes of freedom – Vesey, Turner, Cinque, Washington – noble men and heroes.

In 1822, Denmark Veazie [Vesey], of South Carolina, formed a plan for the liberation of his fellow men. In the whole history of human efforts to overthrow slavery, a more complicated and tremendous plan was never formed. …That tremendous movement shook the whole empire of slavery. The guilty soul thieves were overwhelmed with fear. It is a matter of fact, that at that time, and in consequence of the threatened revolution, the slave States talked strongly of emancipation. But they blew but one blast of the trumpet of freedom and then laid it aside.

The patriotic Nathaniel Turner followed Denmark Veazie [Vesey]…, and future generations will remember him among the noble and brave…Next arose the immortal Joseph Cinque, the hero of the Amistad…Next arose Madison Washington that bright star of freedom, and took his station in the constellation of true heroism. He was a slave on board the brig Creole,

Noble men! Those who have fallen in freedom’s conflict, their memories will be cherished by the true hearted and the God fearing in all future generations; those who are living, their names are surrounded by a halo of glory.

Like David Walker fourteen years earlier, Garnet ends with a plea to the Four Million to “strike for your lives and liberties” against those “defiling your wives and daughters.”

Brethren, arise, arise! Strike for your lives and liberties. Now is the day and the hour. Let every slave throughout the land do this, and the days of slavery are numbered. You cannot be more oppressed than you have been¬—you cannot suffer greater cruelties than you have already. Rather die free¬men than live to be slaves. Remember that you are FOUR MILLIONS!

It is in your power so to torment the God cursed slaveholders that they will be glad to let you go free…. But you are a patient people. You act as though, you were made for the special use of these devils. You act as though your daughters were born to pamper the lusts of your masters and overseers. And worse than all, you tamely submit while your lords tear your wives from your embraces and defile them before your eyes. In the name of God, we ask, are you men? Where is the blood of your fathers? Has it all run out of your veins? Awake, awake; millions of voices are calling you! Your dead fathers speak to you from their graves. Heaven, as with a voice of thunder, calls on you to arise from the dust.

Let your motto be resistance! resistance! RESISTANCE! No oppressed people have ever secured their liberty without resistance. What kind of resistance you had better make, you must decide by the circumstances that surround you, and according to the suggestion of expediency. Brethren, adieu! Trust in the living God. Labor for the peace of the human race, and remember that you are FOUR MILLIONS.

Everything about Garnet’s speech is anathema to the South. It recalls decades-old memories of the Vesey and Turner attacks, and the more recent adverse legal decisions in the Amistad and Creole cases. It calls out politicians who would expand slavery into Texas and Mexico, along with Christian clergymen who would defend it where it already exists.

It reminds owners of the blood already on their hands and invokes the image of blood to be spilled by four million angry Africans seeking revenge.

As such, it will soon provoke a backlash across the South, led in part by the clergy.