Section #14 - Anti-Slavery sentiment grows due to the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Chapter 159: Two More Southern Conventions Search For A Political Strategy On Slavery

Winter 1850

Concerns Remain Over The 1850 Compromise

While Fillmore tries to convince himself that the 1850 Bill resolves the sectional divide over slavery, the South remains fearful that the national tide is turning against them.

Their concerns prompt the call for two conventions, one in Nashville in November and a second in Georgia in December.

Two distinct camps, cutting across party lines, will argue their positions at each event.

On one hand, the radical Secessionists, who argue that political power has shifted to Northerners intent on banning the spread of slavery to the west and thereby crushing the economic engine of the South. They say that the only sane response to this prospect is to break away from the Union.

On the other, the Unionist camp, still regarding the 1787 Constitution as a sacred contract which, in the end, will lead honorable Northern men to accommodate to Southern necessities. This was the case at Philadelphia and again in 1820 over Missouri. Surely the 1850 Compromise holds the possibility for “liberty and union.”

November 11-18, 1850

The Second Nashville Convention Takes A More Threatening Stance

The Nashville gathering is a follow-up to the very contentious meeting back in June 1850, where Mississippi Governor John Quitman’s call for immediate secession was rejected as too extreme by the mostly Unionist delegates.

Their alternative at the time called for convincing Taylor and Clay to solve the slavery debate by extending the 36’30” Missouri line of demarcation to the west coast.

Instead, the best that Stephen Douglas can deliver is to freeze both New Mexico and Utah in “territorial limbo” and delay final calls on Free vs. Slave State status until constitutions are written and a “pop sov” vote is held.

This outcome prompts the second Nashville Convention lasting eight days and arriving at a considerably more threatening consensus. The final manifesto approved by the delegates begins by drawing the now well-rehearsed distinctions between the white and black races:

We have amongst us two races, marked by such distinctions of color and physical and moral qualities as forever forbid their living together on terms of social and political equality.

The Constitution sanctioned the master-slave relationship between the races – and any retreat would be just cause for the South to secede.

The black race have been slaves from the earliest settlement of our country, and our relations of master and slave have grown up from that time. A change in those relations must end in convulsion, and entire ruin of one or of both the races.

When the Constitution was adopted this relation of master and slave, as it exists, was expressly thresholded and guarded in that instrument. It was a great and vital interest, involving our very existence as a separate people then as well as now. The states of this confederacy acceded to that compact, each one for itself, and ratified it as states. If the non-slaveholding states, who are parties to that compact, disregard its provisions and endanger our peace and existence by united and deliberate action, we have a right, as states, there being no common arbiter, to secede.

It now appears that the federal government is committed to limiting this spread of slavery and thereby disrupting the balance of power between the sections in the congress.

Restrictions and prohibitions against the slaveholding states, it would appear, are to be the fixed and settled policy of the government; and those states that are hereafter to be admitted into the Federal Union from their extensive territories will but confirm and increase the power of the majority; and he knows little of history who cannot read our destiny in the future if we fail to do our duty now as free people.

Southerners are further outraged by what they regard as personal attacks on their honor in “gross misrepresentations of our moral and social habits…before the world.”

We have been harassed and insulted by those who ought to have been our brethren, in their constant agitation of a subject vital to us and the peace of our families. We have been outraged by their gross misrepresentations of our moral and social habits, and by the manner in which they have denounced us before the world. Our peace has been endangered by incendiary appeals. The Union, instead of being considered a fraternal bond, has been used as the means of striking our vital interests.

The “vital interests” of the South are also being threatened in California and in Texas.

The admission of California, under the circumstances of the ease, confirms an unauthorized and revolutionary seizure of public domain, and the exclusion of near half the states of the confederacy from equal rights therein destroys the line of thirty-six degrees thirty minutes…compromise.

The recent purchase of territory by Congress from Texas, as low down as thirty-two degrees on the Rio Grande, also indicates that the boundaries of the slaveholding states are fixed and our doom prescribed so far as it depends upon the will of a dominant majority.

Given these circumstances, the delegates go on to offer up a series of six “resolves:”

1. That we have ever cherished, and do now cherish a cordial attachment of the constitutional union of the States

2. That the union of the States is a union of equal and independent sovereignties, and that the powers delegated to the Federal government can be resumed by the several states, whenever it may seem to them proper and necessary.

3. That all the evils anticipated by the South, which occasioned this Convention to assemble have been realized, by the failure to extend the Missouri line of compromise to the Pacific ocean…the admission of California as a state…the organization of Territorial…Utah and New Mexico without…adequate protection for the property of the South… the dismemberment of Texas (and) by the abolition of the slave trade, and the emancipation of slaves carried into DC for sale.

4. That we earnestly recommend to all parties in the slaveholding States, to refuse to go into…any national convention… to nominate candidates for the Presidency and Vice Presidency… under any party denomination…until our constitutional rights are secured.

5. That in view of these aggressions…we earnestly recommend to the slaveholding states, to meet in a.. convention to be …composed of double the number of their senators and representatives in the Congress of the United States…to deliberate and act with a view and intention of arresting further aggression, and if possible of restoring the constitutional rights of the South, and if not to provide for their safety and independence.

6. That the president of this convention…forward copies of the foregoing preamble and resolutions to the governors of each of the slave-holding States of the Union, to be laid before their respective legislatures at their earliest assembling.

December 6-10, 1850

The “Georgia Platform” Convention Reaffirms A Pro-Union Stance

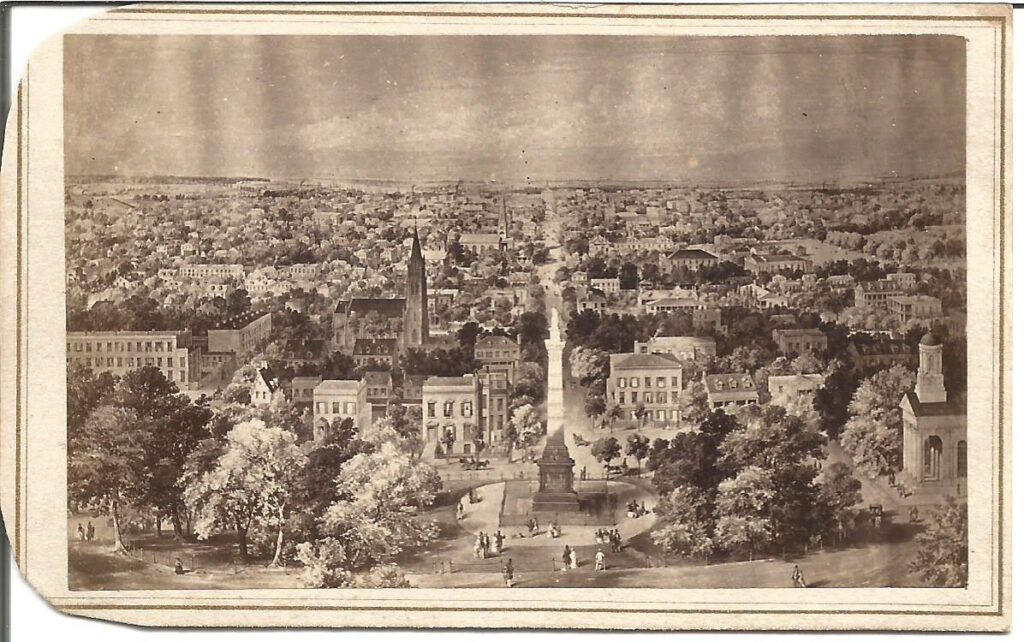

The Georgia convention is held in Milledgeville, in December 1850. It is called by Governor George Towns with the express purpose of deciding how his state should respond to the 1850 Compromise.

The meeting is preceded by intense campaigning by two sides to select delegates.

Those opposing the 1850 Bill include Towns himself along with ex-Senator Herschel Johnson, both classical Jackson Democrats and both dismayed by the “containment” tactics of the North. Their recruitment efforts are joined by two States Rights firebrands, William Yancey of Alabama and Robert Rhett of South Carolina.

Those supporting the bill are led by the three prominent Georgians in the U.S. House – the powerful Democratic Speaker, Howell Cobb, and his two Whig allies and lifelong colleagues, Robert Toombs and Alexander Stephens.

When the voting on delegates is in, a two-thirds majority are in favor of sending Unionist delegates to the convention. This signals what still seems to be the prevalent wishes of most Southerners – to reaffirm their commitment to the Union and recognize the need for all to compromise once again to preserve it.

As Jackson declared in 1833: “our federal Union – it must and shall be preserved.”

The convention itself last for five days and produces a pivotal document titled “The Georgia Platform” which plays an important role in holding the Union together at the time.

It is approved on December 10, 1850, and announces the “conditions” demanded by the state to sustain the Union. The document opens with a re-statement of the 1850 Compromise details, which the proceedings say Georgia will “abide by although not wholly approving of, as a permanent adjustment to the sectional controversy.”

The Platform, however, also ends with a threat stating that Georgians will be ready to secede if the federal government:

- Threatens the safety, domestic tranquility, rights, or honor of the slave-holding states;

- Refuses to admit as a state any territory because it has slave-holders in its boundaries;

- Prohibits the introduction of slaves into the territories of Utah or New Mexico; or

- Repeals or modifies the laws on recovery of fugitive slaves.

These threats play an important role in the overall declaration. Georgia wishes to preserve the Union, but it will not be pushed around by Northern violations of its Constitutional rights.

Over the next decade, the Georgia Platform will play a crucial role in holding the South in the Union.

It will eventually spawn the Constitutional Union Party, which represents the last dying gasp of Southerners who likely view secession as a perhaps even treasonous betrayal of the America they have fought to preserve.