Section #22 - The Southern States secede and the attack on Ft. Sumter signals the start of the Civil War

Chapter 269: Three More Southern States Secede Amid Calls For Calm

January 9-11, 1860

Other States Follow South Carolina’s Lead

Once word of the confrontation in Charleston Harbor spreads, the gates open for other states to follow South Carolina’s lead, and three do so in quick order:

Secession Timing: First Four

| Dates | States |

| December 20, 1860 | South Carolina |

| January 9, 1861 | Mississippi |

| January 10, 1861 | Florida |

| January 11, 1861 | Alabama |

The Mississippi convention delegates vote 83-15 in favor of disunion, with an ordnance declaring:

We embrace the alternative of separation; and for the reasons here stated, we resolve to maintain our rights with the full consciousness of the justice of our course, and the undoubting belief of our ability to maintain it.

A celebration accompanies the decision: “Oxford is brilliantly illuminated… and bells are ringing, and guns are being fired. Three cheers for our gallant State!!”

At Tallahassee, Florida passes its ordnance by a 62-7 margin. A special state flag created to mark the departure reads: “The Rights of the South at All Hazards.”

Alabama meets at its Montgomery on January 11, with pro-Unionist supporters in the northern districts making for a closer 61-39 vote to secede.

At this point a total of three Slave States have opted out with twelve more yet to be heard from.

January 11, 1860

Jefferson Davis Seeks A Pause To Prepare For Possible War

Once Mississippi secedes, its Senator Jefferson Davis anticipates that Florida, Alabama and others will follow, and that an independent Southern confederation will be established, along the lines of that proposed thirty years ago by John C. Calhoun.

Davis is, however, uncertain about the likely response from the existing federal government. Will it allow a peaceful exit or attempt to stop it by force? If the latter, the seceding states will need time to organize a command structure and prepare to defend itself.

His fear is that the volatile events ongoing in Charleston Harbor may explode into widespread civil war before the southern coalition is prepared to fight.

The man in the middle of this at the moment is South Carolina Governor Pickens who continues to send threatening messages to Major Anderson at Ft. Sumter.

Davis and his military advisors decide to try to convince him to “pause” for the time being.

January 11, 1860

Pickens And Anderson Arrive At A Plan

Still without orders from Washington, Anderson sends Lt. Norman Hall ashore with a message denouncing the attack on the Star, and stating his intent to turn his guns on any further interference from the rebel batteries.

Pickens replies that the “first act of positive hostility” was Anderson’s move from Moultrie to Sumter, and thus the repulse of the supply ship was fully justified.

But Picken’s military advisors also warn him that a bloody siege will be needed to reduce Sumter, and that the return fire from Anderson’s troops will do severe damage to the other city defenses.

Still Pickens decides to make one more attempt to capture the fort with rhetoric. On January 11, 1861, his envoys arrive with a letter demanding his surrender. Anderson reads it and replies on the spot:

I cannot do what belongs to the Government to do. The demand must be made upon them and I appeal to you as a Christian, as a man, and as a fellow country-man, to do all you can to prevent an appeal to arms.

He then makes a suggestion that will profoundly affect the national struggle, proposing to…

Send an officer, with a messenger from the Governor, to Washington (and) will do anything that is possible and honorable to prevent an appeal to arms.

Governor Pickens is delighted by this outcome, and Lt. Norman Hall and Isaac W. Hayne, the South Carolina Attorney General, depart for DC that same day.

The effect of Anderson’s action will be the desired “pause” which gives both sides the opportunity to contemplate their next moves.

January 2, 1860

Henry Seward Attempts To Deescalate The Tension

On January 12, another voice at the center of the turmoil is heard in the upper chamber.

It belongs to Senator Henry Seward of New York, assumed by all to be headed into Lincoln’s cabinet, and by many to emerge as the real power behind the presidency.

Seward warns the packed assembly of the perils that would follow Disunion. It would mean…

Perpetual civil war…(and) not only arrest, but also extinguish, the greatness of this country.

That said, his audience awaits word from Seward on how the crisis will be averted.

But he has little to offer. He states his willingness to support iron clad protections maintaining slavery in states where it already exists, and offers up the notion of routing transatlantic railroads along both southern and northern routes to help bind the nation together around commerce.

Beyond that, his plea is simply for “calm” – a call not dissimilar from that issued by Jefferson Davis before him.

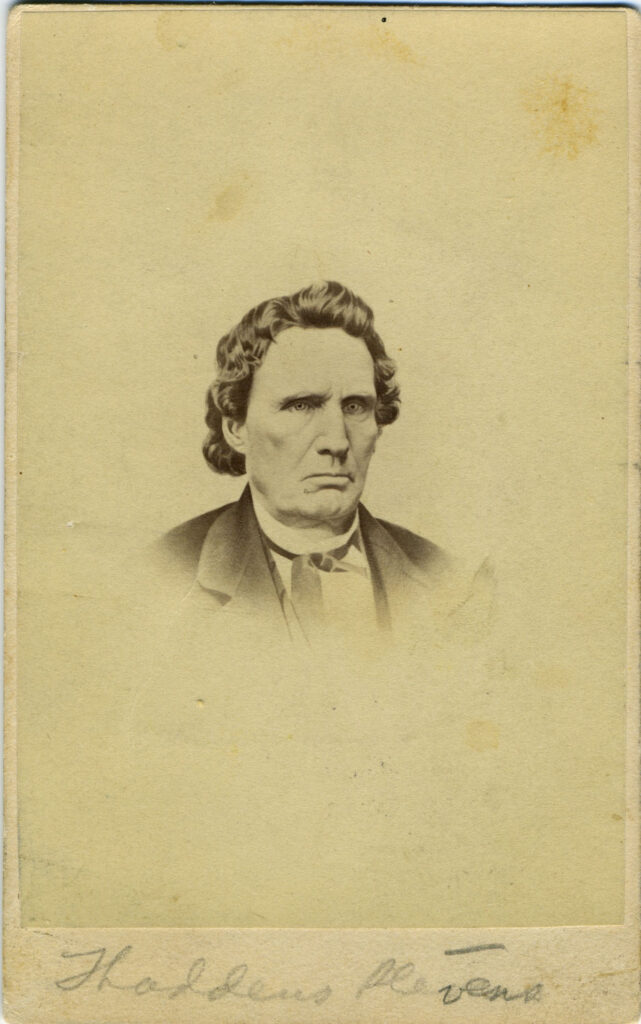

Those most distressed by Seward’s remarks are the Northern abolitionists, or “ultras.” In addition to second term Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, who despises Seward as a “compromiser,” the acerbic Pennsylvanian, Thaddeus Stevens, has this to say:

I listened to every word, and by the living God, I have heard nothing.

An exasperated Seward tells his wife at the time:

I am the only hopeful, calm, conciliatory person here.

For those, particularly in the military, who see a much greater and more immediate threat from the South the question is whether either Seward or Lincoln really grasp the danger. This uncertainty will continue as the transition of power draws nearer.