Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

Chapter 122: The Wilmot Proviso Is An Existential Threat To The South

August 8, 1846

Wilmot’s Proviso Signals A New Crisis

Polk is enjoying a remarkable string of victories when everything he has accomplished is suddenly threatened by a crisis in the U.S House.

The impetus here is a straight forward appropriations bill to set aside $2 million to fund the Mexican War, which the President hopes to pass in the final two days before the 29th Congress adjourns for recess.

Polk fully expects the bill to prompt the usual criticism of the war from his Whig opponents, and this occurs when the New Yorker, Hugh White, says the conflict is a Southern plot to “extend the limits of slavery” into the west. He promises to vote against funding the war unless the language in the bill…

Forever precludes the possibility of extending the limits of slavery…and I call upon the other side to propose such an amendment…as evidence of their desire to restrain that institution within it constitutional limits.

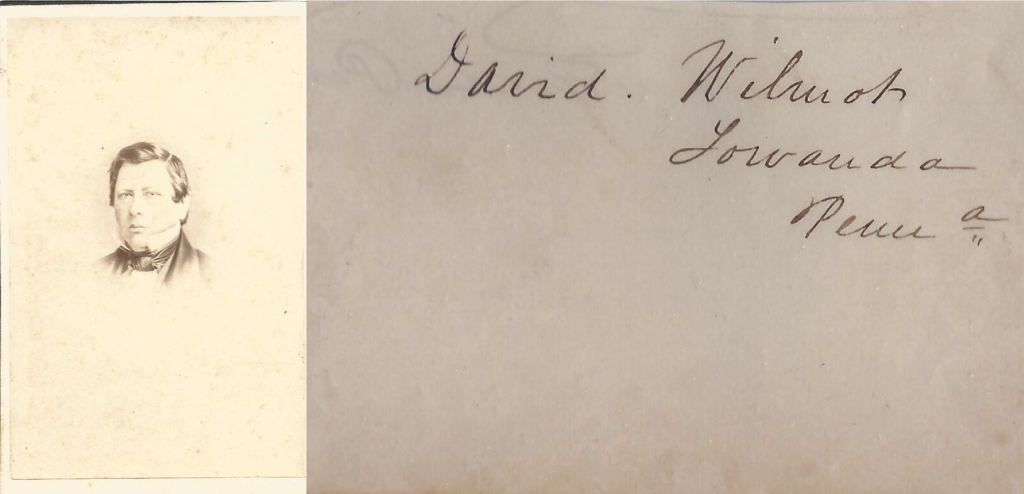

The next member to speak is first-term Democrat congressman David Wilmot, representing the 12th district of Pennsylvania.

Wilmot is only 32 years old, but imposing in stature, sporting a chaw of tobacco, and ever ready to buck the system on behalf of speaking his mind. After being recognized by the Speaker as a likely-to-be-friendly voice in the storm, Wilmot announces that he will support Polk’s bill, but only if a “proviso” is added.

Provided, That, as an express and fundamental condition to the acquisition of any territory from the Republic of Mexico by the United States, by virtue of any treaty which may be negotiated between them, and to the use by the Executive of the moneys herein appropriated, neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any part of said territory, except for crime, whereof the party shall first be duly convicted.

His fellow Democrats are stunned by his declaration!

When asked to explain his amendment, he says that he voted for the Texas annexation, and has no moral qualms over slavery, nor any wish to abolish it. Rather his intent is simply to preserve “free soil” out west in order to “uphold the dignity of white men’s labor.”

I would preserve for free white labor a fair country, a rich inheritance where the sons of toil of my own race and color, can live without the disgrace which association with negro slavery brings upon free labor….If free territory comes in, God forbid that I should be the means of planting this institution upon it.

In this moment Wilmot offers up a new rationale for opposing slavery.

It is directed at upholding the value of white men’s labor, not ending the black man’s suffering. To achieve this end, it flat out prohibits any further spread of slavery.

As such it is the worst nightmare for Polk and the men of the South – and it originates with a Democrat!

1844-1846

The Complex Roots Of Rebellion Among Northern Democrats

Once Wilmot’s shocking Proviso is out in the open, Polk’s supporters scurry to identify its origin and to determine just how much support it has, especially within the Democrat Party.

What they learn is deeply distressing.

Wilmot’s dissent is widely shared among Northern Democrats, and aimed at Polk and the Southern wing of the party. Its origins trace all the way back to the 1844 Nominating Convention, where many feel that Van Buren was robbed of his chance for a second term.

Much of it is concentrated in New York, especially among men “Van Buren men” like Senator John Dix and Governor Silas Wright.

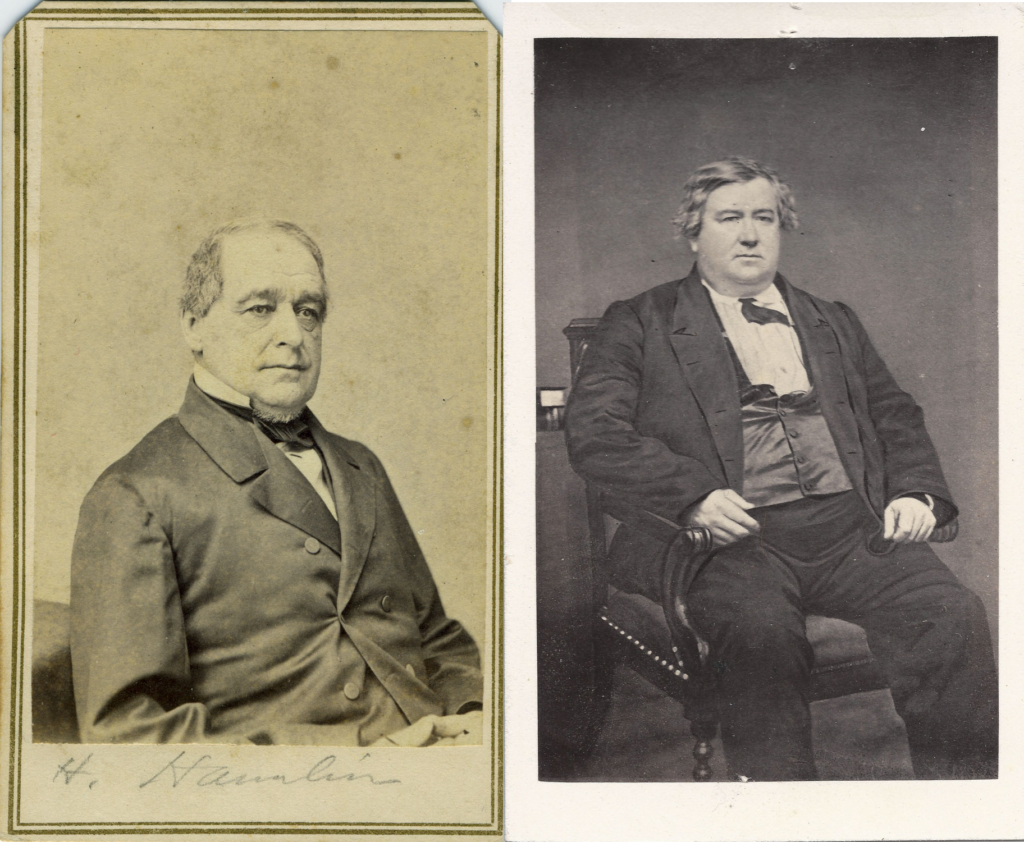

They are joined by others, including Preston King of New York, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, and Jacob Brinkerhoff of Ohio, who go beyond sheer political animosity and see a Southern cabal at work, one determined to take over the party and put a pro-slavery man in the White House who will back their regional agenda.

This opposition group becomes known as the “Barnburner Democrats,” accused by other members of being more willing to destroy the party than to back the President. Indeed many will assert that it is actually Brinkerhoff or Preston, rather than Wilmot, who pens the August 8 Proviso in the first place.

Other factors also play into this notion that the “Slave Power” has co-opted the Democrat Party, to the detriment of Northern interests.

Two powerful Democratic senators, Lewis Cass of Michigan and William Allen of Ohio, have led the “Fifty-four forty or fight” cry to occupy all of the Oregon Country. When Polk compromises with Britain on the 49th parallel boundary, the suggestion is that he will fight for slave territory in Texas, but not for free land in Oregon.

Then there is the Walker Tariff, perceived by many Northerners as a reduction in rates to satisfy the planters of the South at the expense of manufacturing in the east and added infrastructure in the west.

Finally comes the widening of the war against Mexico, no longer confined to disputed land within Texas, but now extending across the Southwest and opening the way to a host of new slave states.

Out of these combined grievances a sizable group of Northern Democrats in the House decide that it is time to send a signal to their Southern colleagues that their interests will not be ignored.

And what better way than to threaten the one thing the Southerners want most – the extension of slave plantations west of the Mississippi?

August 8, 1846

The Wilmot Proviso Passes In The House

With time nearing on a final vote, House Democrats scramble to find an option to the Wilmot Proviso.

The main attempt comes from the Indiana Democrat William Wick, who offers up an alternative solution for all new land west of the Mississippi.

Wick’s proposal is one that will be heard over and over in Congress between 1846 and the collapse of the Union in 1861.

Instead of a universal ban on slavery in the New Territories, why not simply extend the old 36’30” Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific, with states falling south of the line allowing slavery and north of the line prohibiting it. That solved the conflict in 1820 and why shouldn’t it work again in 1846?

The answer in the House is a resounding “no.” Wick’s proposal goes down by an 89-54 margin. At this point, it becomes clear that the usual political calculus has broken down.

The rejection is not a matter of a split along traditional party lines, as in unified Democrats against unified Whigs.

Instead both parties are split along regional lines – with Northern members favoring Wilmot’s ban on extending slavery and Southerners in opposition.

Once this division is clear, Southern forces in the House try to stall. The floor debate continues into the evening, with procedural votes taken on the wording of the Proviso and then on whether to table consideration of the bill until the House reconvenes in December. Both attempts fail.

At last, Polk’s Appropriation Bill with the Wilmot Proviso added comes to a vote. It passes by a narrow margin of 85-80, with only small differences showing up in total between Democrats and Whigs.

House Vote On Appropriation Bill With The Wilmot Proviso Added

| Region | Democrats Yes – No | Whigs Yes – No | American Yes – No | Total Yes – No |

| Northeast | 37 – 0 | 24 – 6 | 5 – 0 | 66 – 6 |

| Northwest | 15 – 4 | 2 – 2 | 17 – 6 | |

| Border | 0 – 9 | 2 – 9 | 2 – 18 | |

| Southeast | 0 – 27 | 0 – 7 | 0 – 34 | |

| Southwest | 0 – 15 | 0 – 1 | 0 – 16 | |

| Total | 52 – 55 | 28 – 25 | 5 – 0 | 85 – 80 |

| Not Voting | (32) | (23) | (1) | (56) |

But looked at along regional lines, the final vote shows that Northern members support Wilmot by 83-12 while Southerners oppose it 68-2.

North Vs. South Split Over The Wilmot Proviso: August 8, 1846

| Region | Democrats Yes – No | Whigs Yes – No | American Yes – No | Total Yes – No |

| North | 52 – 4 | 26 – 8 | 5 – 0 | 83 – 12 |

| South | 0 – 51 | 2 – 17 | — – — | 2 – 68 |

| Total | 52 – 55 | 28 – 25 | 5 – 0 | 85 – 80 |

This outcome is NOT about a moral judgment on slavery, NOT about conscience-stricken Northern whites wishing to end the suffering of Southern slaves.

Rather it is a direct shot by Northerners in both parties across the bow of Polk and the South. It expresses their wish to reserve any new territory in the west for the exclusive benefit of white settlers — unencumbered by the prospect of rich planters trying to buy the best acreage, and black slaves who would erode the “dignity” of their labor, threaten the safety of their families, and diminish the social fabric.

As such, the Wilmot Proviso represents an irreversible line in the sand between Southerners and those in the North and West.

August 10, 1846

Southerners Finally Stall The Wilmot Proviso In The Senate

After the House passes the Wilmot Proviso, all that’s left for the Southern coalition to try to delay a vote in the Senate, until the clock runs out toward recess of the 29th congress on August 10.

This strategy works, despite a filibustering effort by the Massachusetts Senator “Honest John” Davis to force a vote.

On August 10 both chambers adjourn, leaving Polk without the approval of his $2 million appropriation request to fund the war, and the Northerners without the approval of their Wilmot Proviso.

Still, a clear-cut message from the North to the South has been delivered.

The astute Southern leader, John Calhoun, sums it up as follows:

- The North now enjoys a commanding majority of the votes in the House;

- The Wilmot measure shows that the North intends to stop the spread of slavery to the west;

- The South can no longer count on unwavering support for their cause from Northern Democrats;

- Nor does it have a ready-made solution in extending the old 36’20” compromise line.

Unless some new accommodation between the two sections can be found, disunion will be inevitable.

As usual, the South Carolina man accurately foretells the future.

From August 10, 1846 onward, the leaders of congress will begin a 15 year search for a new accommodation capable of holding the nation together.

In the end, they will fail.

August 1846 Forward

The Profound Implications Of The Passage Of The Wilmot Proviso

This vote on the Wilmot Proviso will become a watershed moment in the eventual dissolution of the Union.

It expresses a flat “no” to Southern plans to extend slavery west of the Mississippi, even under the 34’30” line set in the 1820 Missouri Compromise.

It also initiates a dramatic shift in the number of whites willing to stand against the further spread of slavery.

Before Wilmot, this is largely confined to a small eastern band of so-called “radical abolitionists.” After Wilmot, one need not be a “radical” to want to pen slavery up in the South.

That’s because of a new battle cry – “free soil for free men” – that will soon catch fire in the North and West.

It adds two pragmatic reasons against expanding slavery that go beyond mere anti-black racism and fear.

The first is that land prices for western settlers will go way up if average white farmers have to compete with rich plantation owners in the bidding.

The second is more subtle, but every bit as powerful.

It taps into America’s long-standing embrace of the “Protestant work ethic” – the belief that with hard labor comes both dignity and monetary rewards. But, as Wilmot argues, both suffer when blacks are doing the same work as white men, but for free. He calls this a “disgrace” – with white labor diminished to the level of slave labor.

If the value of white labor in America is to be preserved, it must not exist side by side with slave labor.

From this notion new political movements will soon take hold, the Free Soilers, the Know-Nothing Nativists, and eventually the Republican Party. All dedicated to preserving the new western land for white men.

When the South balks at this outcome, it will be branded by more and more Northerners as “the Slavocracy” — forever prioritizing the self-interest of its rich plantation elites over the good of the white settlers.

The savvy abolitionist Lloyd Garrison quickly recognizes the power of this new theme and the Wilmot Proviso votes to serve his own ends, characterizing it as “the beginning of the end of our fight.”