Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

Chapter 109: The Wilkes Expedition Adds Luster To America’s Global Reputation

1838-1842

Lt. Charles Wilkes’ “Exploratory Expedition” Sails Around The World

On June 10, 1842, just as Fremont is starting his journey west in Kansas, another adventurer, naval commander, Lt. Charles Wilkes, sails into New York harbor after completing a four year trip to navigate the globe.

The eventual “Wilkes Expedition” has been a long time in the making. President JQ Adams initiated the idea in 1828, but failed to convince Congress for the funding needed. Andrew Jackson picks up the cause and gains approval in 1836. Still, two more years are needed to organize the six ship flotilla and outfit it properly with some 342 sailors and scientists and necessary provisions. It is officially named the U.S. Exploratory Expedition, abbreviated as the “Ex Ex.”

Overall command belongs with forty year-old Lt. Charles Wilkes, whose surveys of the Narragansett Bay lead to his position as head of the Navy’s Department of Charts and Measurements.

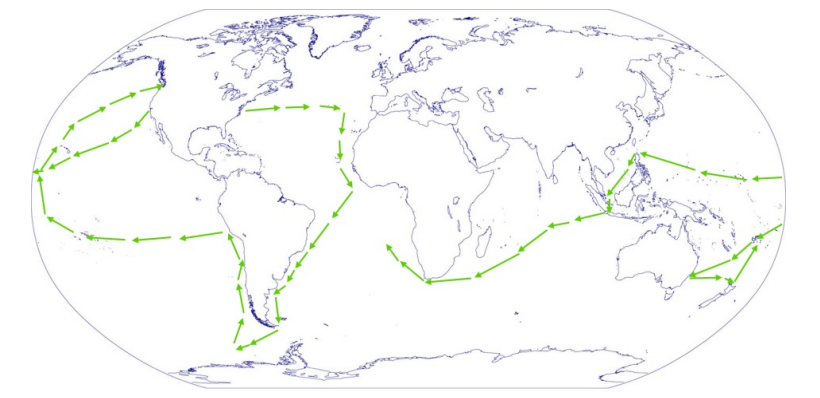

Wilkes’ main objective lies in exploring and mapping the Pacific Ocean, and collecting various earth science data and artifacts at stops along the way. He is aided by all the “modern” tools available to the mariner of his time, to plot exact positions across the oceans.

For millennia, sailors had been relying on celestial navigation – sighting on stars above them at night – to approximate their locations in open water. Around 1730 the first crude sextant is invented to more accurately record the position of the stars at the time of measurement. This enables a ship to determine its latitude, or how far north or south it lies relative to the earth’s Equator. In 1764, the Englishman, John Hadley, solves the other half of the ship location puzzle, by building the first chronometer, a precise marine clock. It enables an accurate measure of longitude, or how far east or west they sit relative to the Prime Meridian, the line leading from the North Pole through the city of London and on to the South Pole. Together these two devices enable the expedition to deliver on their mapping priority.

Wilkes’s crew totals 346 men, including nine scientists, ranging from naturalists to plant biologists, mineralogists, a taxidermist, and an expert in languages. Naval personnel are assigned the tasks associated with collecting positional data and converting it into accurate maps.

On August 19, 1838, the fleet heads out to the open seas from Hampton Roads, Virginia. Since the entire flotilla consists of sailing ships, their course will be determined by the winds they encounter. Thus while their first destination is Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, they are blown directly east to the Madeira Islands before they can tack south. What was to be a six week first leg turns into a frustrating 95-day detour.

Over the next four years the Exploratory Expedition will zig zag its way around the globe, creating detailed maps that will support navigation of future naval vessels and merchant ships alike. It will also spark additional interest in America’s west coast, which Wilke’s explores briefly in the summer of 1841.

Route Taken By The Wilkes’s Expedition

| 1838 | Locations |

| September 16 | Blown east across Atlantic to Madeira Islands |

| November 23 | Back along South American coast to Rio de Janeiro |

| 1839 | |

| Early | Around Cape Horn and north to Chile and Peru |

| Later | Across Pacific to Sydney, Australia |

| 1840 | |

| January 25 | Fleet reaches “ice island” of Antartica |

| July | Fiji Islands where two killed in conflict with natives |

| 1841 | |

| April | Head north to the Gilbert Islands then east toward U.S. |

| July | In Oregon & head south along coast to San Francisco Bay |

| Later | Back west to Pacific and Wake Island |

| 1842 | |

| Early | Further west into Philippines, Singapore, Polynesia |

| Then | Past the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa |

| June 10 | Arrive back home in New York harbor |

The scientists aboard are also busy at every stop doing experiments and collecting artifacts that will describe what they see on the journey. The breadth of the specimens is remarkable.

Scientific and Cultural Specimens Catalogued and Brought Home

| Role | Name | Specimens Brought Back From Voyage |

| Naturalists & Horticuluralists | Charles Pickering, Titian Peale, Wm. Brackenridge, William Rich | 10,000 species of pressed plants, 1,000 live plants, 648 seeds, 2150 stuffed birds, 134 mammals, 588 species of fish and 5300 species of insects |

| Geologist | James Dana | 300 fossils, 400 coral, 1000 crustacea |

| Linguistics and Ethnographist | Horatio Hale | 4000 pieces, from Fiji war clubs to feathered baskets, carved rattles, fishhooks, art work, etc. |

| Artists | Alfred Agate, James Drayton | Tracings of collections using new “camera lucida” to project images onto paper |

Of the 342 voyagers who set out in 1838, a total of 223 return either on the expedition ships or other American vessels. Fifteen have died along the way, 62 have been discharged for cause, and another 42 have deserted.

For Wilkes the homecoming sadly brings additional trials. First, his claim to being the first seaman to reach Antarctica is challenged by both English and French explorers who are in the same region in January 1840. Then complaints about his authoritarian rule throughout the voyage lead to a Naval Court of Inquiry. He is acquitted in July 1842 of all charges save one, for administering more than the maximum twelve lashes to six sailors accused of stealing liquor.

Despite these setbacks, Wilkes finishes up his written record of the voyage, which runs to five volumes and is finally published by Congress in 1845. It is a tedious rendition and fails to earn the fame that Fremont enjoys from the Journals he publishes, perhaps with some ghost-writing help from his talented wife, Jesse.

Meanwhile, the collections from the trip are hailed by its sponsors and by the scientific community, both eager to demonstrate America’s capacity to rival Europe in the arena of basic research and the creation of new knowledge.

As the vast amount of cargo is being off-loaded, the question arises as to where it will be housed. The answer will eventually be America’s first national museum, The Smithsonian Institution.

Sidebar: The Smithsonian Institution Houses The “Ex Ex” Treasures

The challenge of housing artifacts brought back from the Exploratory Expedition provokes an end to the back and forth political haggling about how best to utilize a monetary windfall arriving in America in 1835.

The windfall is 104,960 gold sovereigns, packed in sacks and valued at $500,000, willed to the U.S. Treasury by a British citizen named James Smithson, who dies at age 64 in 1829.

Smithson’s life has been filled with adventure. He is the illegitimate son of an English Duke and a widowed royal mother, who leaves him a sizable inheritance. He uses part of the money to study chemistry and mineralogy at Oxford, where he becomes friends with noted scientists of his era, including Henry Cavendish, famed for his discovery of hydrogen. He travels broadly and is known to have published some twenty-seven scholarly papers, focusing especially on the chemical properties of a zinc ore known as calamine. His work earns him admission to the prestigious Royal Society in London.

When the initial heir to his estate dies without offspring, a clause in Smithson’s will directs the money across the Atlantic to the American government.

I then bequeath the whole of my property, . . . to the United States of America, to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men.

The motivation behind Smithson’s gift remains a mystery. While books in his library include references to the U.S., he has never traveled there, nor does it appear he even met anyone from America. Speculation tends to focus on possible “wounds” in Britain related to his illegitimacy and a sense that the impact of his gift might be greater in a vigorous new nation just beginning to assert its role in science.

Whatever the cause, America is delighted to receive the bounty, which arrives in 1838, only to be lost when an investment in Arkansas bonds goes bust. This injustice is finally righted by JQ Adams who persuades his House colleagues to restore the fund and spend it according to Smithson’s directive.

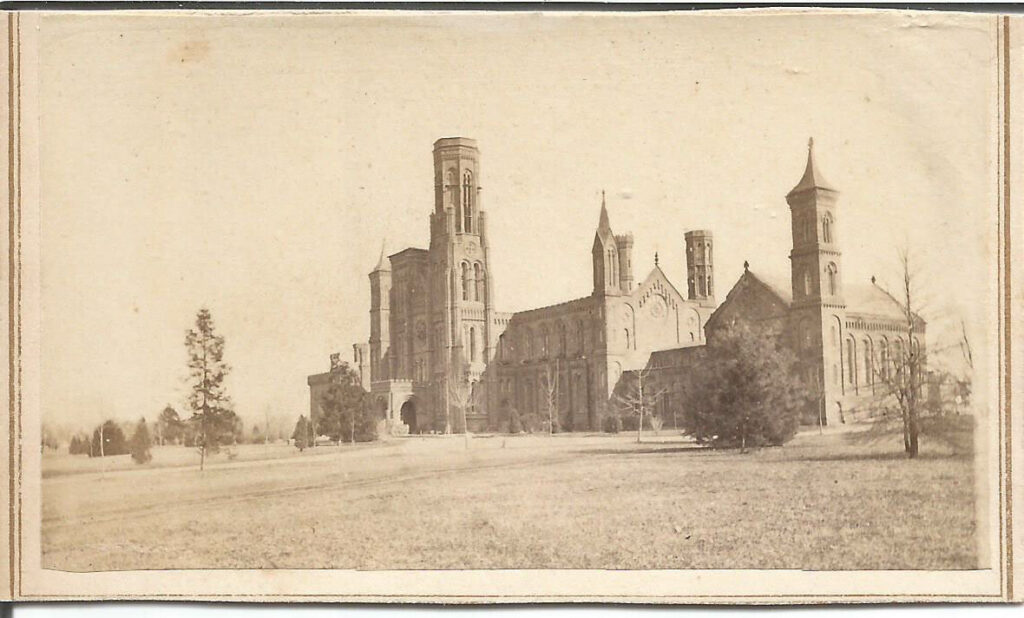

In August 10, 1846, Tyler’s successor, President James Polk, signs legislation to establish The Smithsonian Institution as a perpetual government trust.

While collections from the Wilke’s Expedition (or the “Ex Ex”) eventually end up at the Smithsonian, they are initially stored at the new Patent Office, secured by physician and ex-Secretary of War, Joel Poinsett, an early proponent of America’s scientific development.

Unfortunately, the first curator at The Patent Office totally mishandles the coding of the material before being fired for incompetence. Order is eventually restored first by his initial replacement, Charles Pickering, the lead naturalist on the Ex Ex, and then by Commander Wilke’s himself who christens the Great Hall with a sign in gold letters reading “Collection Of The Exploring Expedition.”

The original Smithsonian building – known as The Castle – is finally completed in 1855 on what is an isolated site about 1.3 miles west of the Capitol., before becoming anchored to the Mall as America’s first national museum.