Section #7 - A populist western president stands against Nullification and for tribal relocation

Chapter 59: The White Abolitionist Movement Finds Its Ongoing Leaders

Late 1820’s

The “Second Awakening” Sparks The Abolition Movement In New York

As the “Second Awakening” spirit of Reverend Charles Grandison Finney builds momentum, it captures three converts in upstate New York who commit to reversing the horrors of slavery – Theodore Dwight Weld and the brothers Tappan, Lewis and Arthur.

Weld is the son of a Congregational minister, who falls under Finney’s spell in 1825 when his aunt convinces him to accompany her to one of his services in Utica, N.Y. He soon discontinues his studies at Hamilton College and enrolls at Oneida Institute – a theological school founded in 1827, and dedicated to the notion that engaging in “manual labor” is a key element in spiritual development.

Oneida is situated on 114 acres of farmland owned by the Presbyterian Church, run by Finney’s mentor, the Reverend George Gale, and supported by Lewis and Arthur Tappan.

The Tappan brothers grow up in Northampton, Massachusetts, become wealthy running a dry goods business in Portland, Maine, and expand their fortune after moving to New York City in 1826 as importers of silk cloth. While raised as traditional Calvinists, the brothers are influenced in part by Finney – who resides in Arthur Tappan’s house for some time – to devote their lives to philanthropy. The Unitarian minister, William Ellery Channing also plays a role at the university, as Lewis Tappan’s pastor.

Lewis meets Theodore Weld on his visits to Oneida and is so impressed that he decides to enlist him in one of the brother’s causes. Weld has already earned a reputation as a powerful preacher on behalf of the dignity of manual labor and the damning effects of drunkenness. But the Tappans have another focus in mind for him – the “sacred cause of Negro emancipation.” He is also encouraged along this path by a lifetime friend, Charles Smart, who becomes involved with anti-slavery efforts in Britain.

Weld’s report to the Tappans about British progress toward emancipation sparks early talk of setting up an American Anti-Slavery Society, but the consensus is that this would be premature.

Nevertheless, the Tappans hire Weld to head their Manual Labor Society. and he works tirelessly on this until he moves to Cincinnati in 1833 to found the Lane Theological Seminary. In 1834 he leads a student debate on slavery that lasts over 18 days and ends with a declaration in support of Abolition.

When the Lane Board of Directors, headed by the President, Lyman Beecher, squash this proposal, the majority of students leave the school, with many headed to nearby Oberlin.

Weld, decides at that time to rejoin the Tappans, who have been busy in their opposition to slavery.

Brother Lewis donates $10,000 to get Oberlin College up and running by 1833. Arthur, meanwhile, supports an all-black college in New Haven in 1831 and has his house stoned by local citizens in return.

Soon thereafter, the Tappans encounter another abolitionist, Lloyd Garrison, and agree to join forces in fighting slavery. Together they form the two great wings of the white abolitionist movement in America:

- The New York wing, comprising Theodore Weld and the Tappan brothers, later joined by Gerrit Smith and James Birney; and

- The Boston wing, Lloyd Garrison, Ben Lundy, Lucretia Mott, and a host of their other supporters, including black figures such as Fred Douglass and Sojourner truth.

Over the next thirty years, these Abolitionists will risk their welfare and their very lives on behalf of ending slavery in America.

Late 1820’s

William Lloyd Garrison Emerges As The Nation’s Leading Spokesperson

(1805-1879)

In 1828 a chance meeting at a Boston boardinghouse between two fiery newspapermen and moralists changes the future trajectory of the abolition movement.

One participant is the 39 year old Quaker, Benjamin Lundy, whose paper, The Genius of Universal Emancipation, has railed against slavery for the past seven years. The other is 23 year old Baptist, William Lloyd Garrison, a budding journalist since thirteen, and eager to find the right cause for his own paper.

Lundy convinces Garrison to attack slavery as a worthwhile calling, and from then on, over the next three decades, Garrison will emerge as the acknowledged leader of the Abolitionist movement in America.

Three things will set Garrison apart from all but a handful of others in the cause:

- His demand that emancipation be “immediate” rather than gradual;

- His support for keeping freed blacks in America, not returning them to Africa; and

- His unique and unequivocal commitment to assimilation of blacks as full and equal citizens.

In effect, his appeals as a white man mirror those of the contemporary black reformer, David Walker.

Garrison is shaped for his mission as a child, by his mother, Fanny Garrison, whose alcoholic husband abandons his family in Newburyport, Massachusetts when Lloyd is only three,

From then on, Fannie struggles to provide for her two sons and herself, working odd jobs and often needing to place the boys in foster homes around town. Despite her difficulties, she is forever buoyed by her Baptist faith and is known to her congregation as “Sister” Garrison, Nothing matters more to Fanny than passing on her revivalist fervor to her sons and daughter. Together they attend church services three times every Sunday, and young Lloyd takes to humming what will become a favorite psalm: “my heart grows warm with holy fire.”

By 1818 the family’s financial straits grow even more desperate, and Lloyd, age thirteen, begins a job as a “printer’s devil” for the Newburyport Herald. This job changes his life. He is smitten by all the intricacies of the newspaper trade, and masters them so quickly that he is soon an indispensable part of the operation, as shop foreman. The owner of the paper, Ephraim Allen, also opens his personal library to Lloyd – and he schools himself in Shakespeare and Milton and the adventure tales of Scott and Byron. His imagination carries him to the possibility of his own form of heroic action on behalf of a cause that his mother would applaud.

In 1822 Lloyd recognizes the power of the newspaper to express and disseminate his thoughts to the public. He begins to write his own articles, and sees that the early poems of his friend, John Greenleaf Whittier, get published.

Then tragedy strikes, as both his mother and younger sister pass away due to illness in 1823. Sister Garrison’s final message to her son marks his future.

Dear Lloyd – Lose not the favor of God, have an eye single to His glory and you will not lose your reward.

Now on his own at age 21, Lloyd ends his apprenticeship and launches his own newspaper, The Free Press, then shuts it down when his former employer is upset by the new competition.

Garrison makes his way to Boston in 1826, a major city of 60,000 people, teeming with enterprise and universities and churches. Here he finds the common man and the intellectual class, a small enclave of free blacks, and a heavy dose of revivalism. Garrison renews his religious ties and is touched by both the Reverend Lyman Beecher – “the way to get good is to do good” – and the Unitarian William Ellery Channing, with his gentle admonition to save yourself by acting morally.

Garrison now commits himself to helping humanity through a “life of philanthropy,”

He first chooses Temperance as his cause. Both his father and his older brother ruined their lives through drink, and perhaps he can persuade others to escape their fate. His vehicle for this task will be a newspaper, and in January 1828 the first issue of The National Philanthropist appears. While the editorial content focuses on the perils of alcohol and the saving grace of temperance, Garrison also begins to dabble in Federalist politics. However, he concludes that traditional politics are self-serving and power hungry, and that his focus should remain on “moral politics.”

At this point in his life comes his chance encounter with Friend Ben Lundy and along with it, his calling the eradication of slavery. After hearing Lundy’s pleas, his response is immediate:

My soul was set on fire then.

January 1, 1831 – December 29, 1865

Garrison Publishes His Abolitionist Paper The Liberator

Garrison begins his personal crusade by trying to set up an Anti-Slavery Society in Boston, but is rebuffed by locals arguing that it’s a Southern problem, not theirs. This resistance angers Garrison and steels him to his task.

He abandons the city briefly for a job in Burlington, Vermont on a pro- JQ Adams newspaper. There he foments political outrage by writing that Andrew Jackson “should be manacled with the chains he has forged for others” as a slave owner.

What he learns from this stint is the power of inflammatory language to gain attention to his cause.

Upon returning to Boston he takes this lesson into an 1829 public speaking appearance before 1500 attendees at the Park Street Church, in celebration of the 4th of July. Here he is transformed into the Puritan Zealot, exhorting his audience with what will become familiar themes:

- Slavery is a national sin – let us be up and doing to stop it.

- We have a common interest in demanding abolition.

- Would we stand still if slave were suddenly to become white?

- I tremble for the Republic while slavery exists.

Pushing even farther, he points to Haiti as evidence of the Africans capacity for “equal citizenship.”

His conviction about integrating the Africans into white society grows from there, as he mixes with Black people living in the enclave on Beacon Hill. This experience tells him that abolition should take place immediately, not gradually, and that he should speak out against re colonization.

Even those sympathetic to his cause begin to express discomfort with the call for “Immediatism.” Thus the Unitarian minister, Ellery Channing, writes to Daniel Webster: “watch out for rashness of enthusiasts.”

But nothing slows Garrison. In the summer of 1829 he moves to Baltimore, re-uniting with Lundy and agreeing to co-publish his newspaper, The Genius of Universal Emancipation. The two split the editorial tasks – Lundy backing a more moderate path and re-colonization, and Garrison heightening his attacks on the status quo. He calls slave holders “man-stealers;” says that “our politics are rotten;” and offers a column called The Black List: Horrible News of the Day.

A turning point for The Genius comes when Garrison convinces Lundy to publish Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World.

Suddenly the paper’s white audience is confronted by the face of slavery as seen through the eyes of those who have endured “wretched lives” under the lash. That much is shocking to readers.

But along with Walker’s appeal to free the slaves now and live alongside them peacefully in America was equals, comes a threat – if whites fail to act, blacks will take up arms and kill them for freedom.

When copies of the paper containing Walker’s Appeal reach Southern cities, the cry goes up for Garrison’s head – for inciting blacks to flee and to murder their masters.

Still he persists. On April 17, 1830 he is found guilty of libel for accusing a man in Baltimore of slave trading. When sentenced to six months in prison or a $70 fine, he embraces his martyrdom:

A few white men must be sacrificed to open the eyes of this nation and to show the tyranny of our laws.

He remains in jail for 49 days until Arthur Tappan hears his plight and sends him $100 to get out.

Upon his release, Lundy urges “moderation,” as does the Congregationalist preacher, Henry Ward Beecher, who tells him: “if you give up your fanatical notions, and be guided by us, we will make you the Wilberforce of America” – Wilberforce being the lead proponent of abolition in Britain at the time.

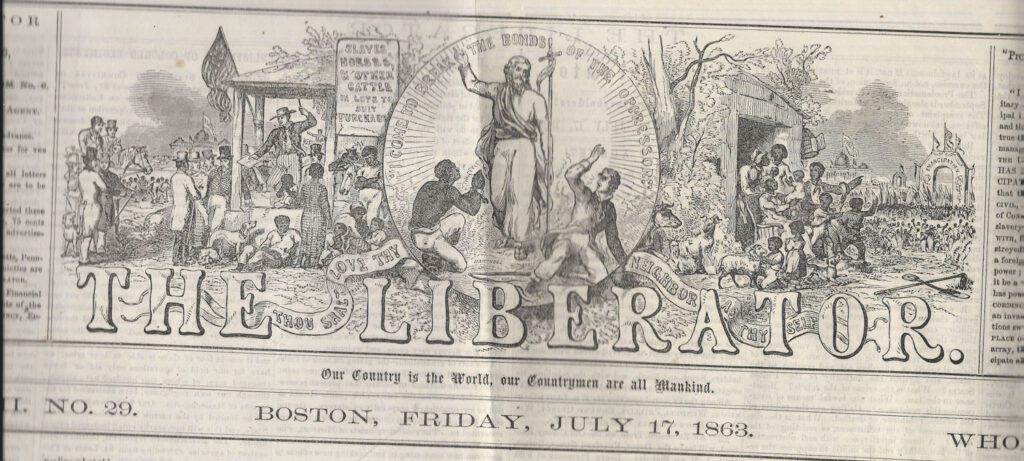

Garrison will have none of this, and concludes that the time has come for him to publish his own newspaper, which he starts up in Boston on January 1, 1831. He names the paper The Liberator, and will continue to write, print and distribute it weekly for the next 35 years, until the 13th Amendment, freeing the slaves, is finally passed in Congress.

His manifesto is crystal clear from the start: the national sin of slavery must end immediately, and all blacks must be assimilated into American society as full and equal citizens. His tonality is also clear:

“I am in earnest – I will not equivocate – I will not excuse – I will not retreat a single inch –

AND I WILL BE HEARD!”