Section #16 - Open warfare in “Bloody Kansas” follows fraudulent election wins for Pro-Slave State forces

Chapter 193: The “Wakarusa War” Presages Greater Violence To Come In Kansas

Winter 1855

The Two Camps In Kansas Prepare For Open Warfare

In parallel with their efforts to form their “legitimate government,” the Free Staters also ready themselves to go to war with the Missouri men if need be.

Their preparations begin early in 1855 with the formation of the “Kansas Legion,” another secret order with members whose members wear black ribbons and who define their mission as:

First, to secure to Kansas the blessing and prosperity of being a Free State; and secondly, to protect the ballot box from the leprous touch of unprincipled men.

Securing the armaments needed for potential combat is a priority for the Free State men, and they send James Abbott, an early New England Emigrant Aid Society transplant, back east to contact Eli Thayer for help. Ironically two abolitionist preachers, Henry Ward Beecher and Thomas Higginson, respond with a shipment of 117 Sharp’s rifles, crated up in boxes, marked “Bibles,” and sent west – along with one 12 lb. howitzer, canister and fused shells.

The eastern press hears of this move and christens the cargo “Beecher’s Bibles.”

At the same time, the Pro-Slavery forces are also preparing for battle. On October 3, 1855, they organize a “Law and Order” posse dedicated to putting down “treason” in Kansas. In mid November they meet in Leavenworth, with Governor Shannon present, to plot their strategies.

Both sides are now prepared to win through violence.

November 21, 1855

A Dispute Over A Land Claim Lights The Fuse

The bloodshed begins on November 21, when Charles Dow is murdered by Franklin Coleman in Hickory Point, Kansas, setting off what becomes known as the “Wakarusa War.”

The motive for murder is not about slavery, but rather a heated dispute between the two neighbors over ownership of a 250 yard strip of land adjacent to their homes. The weapon is a shotgun, which leaves Dow bleeding to death in town, while Coleman retreats to his home to await arrest for his act.

Dow happens to be a Free State backer, and his friend, Jacob Branson, collects his body and has it buried. He then organizes a Free State “committee of vigilance” meeting on November 26 to decide how to avenge the death. A posse is formed to capture Coleman, but it ends up burning down his house after learning he has fled to Missouri.

When Branson returns home, he is arrested by Sheriff Samuel Jones for “disturbing the peace.”

As Jones tries to take Branson to jail, he encounters a band of Branson’s Free State friends who threaten violence to gain his release. Jones responds with restraint by surrendering Branson, who returns to Lawrence and the safety of Charles Robinson’s home.

From there, tensions mount quickly. Sheriff Jones informs Governor Shannon of Branson’s abduction. Shannon responds by calling out the territorial militia and issuing a public plea for help to restore law and order. The public response is more than the Governor bargains for, as roughly 1500 Pro-Slavery Missourians show up, all eager to attack the town of Lawrence and kill Branson along with his backers.

December 8, 1855

The “Wakarusa War” Is Resolved By Cooler Heads

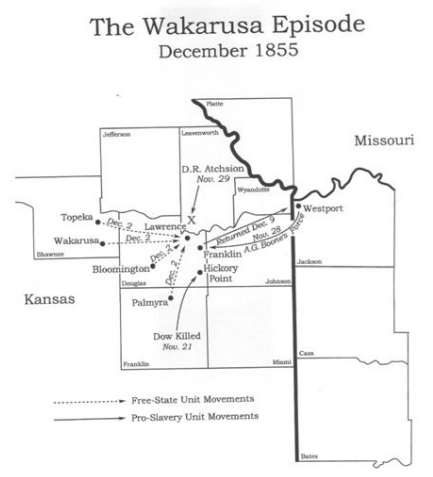

The Missouri raiders assemble their main camp below the Wakarusa River, running west to east, just south of Lawrence, and prepare for a siege by establishing blockades along all roads into town.

Free State defenders inside Lawrence prepare a series of circular earthen forts, some seven feet high and one hundred feet across, along with connecting trenches and other rifle pits. They are commanded by James Henry Lane, who begins to earn his lasting nickname as “The Grim Chieftan.”

As the siege begins, so too do negotiations involving Governor Shannon and both sides.

Violence is avoided until the afternoon of December 6, when three perhaps unwitting Free State riders are stopped on a road leading to their homes, and interrogated as to their intentions. After guns are drawn, two men escape, but a third, named Thomas Barber, is killed by the Missourians.

Word of Barber’s death reaches Governor Shannon, who now fears that his militia units will be unable to stem a full out assault on Lawrence by the Pro-Slavery troops.

To forestall more bloodshed, Shannon meets both sides between the evening of December 6 and December 8, to work out a peaceful settlement. Here he enjoys a moment of success when an agreement is signed by ex-Senator David Atchison, Charles Robinson and James Lane. Its content is relatively anodyne: in exchange for no longer harboring Jacob Branson from prosecution (even though he has already left town), the government will lift the siege and not hold the citizens of Lawrence in contempt of the law.

For those in Lawrence, the outcome is regarded as a victory – and a gala ball is held to celebrate. Their city is intact; the Pro-Slavery forces have backed away; and the slain Thomas Barber will not have died in vain. To insure their future protection, Governor Shannon, perhaps inebriated at the time, has also authorized the Free Staters to form their own protective militia, something he will later regret.

The response among most of the Border Ruffians is the exact opposite. Not only have they been deprived of the military victory they prepared for at Lawrence, but both Jacob Branson and the Free State “nullifiers” have escaped without punishment. David Atchison, who signed the accord, defends his action by saying that a slaughter would have built sympathy in the North for a Free Kansas, and forced Washington to take a closer look at the legitimacy of the Pro-Slavery election wins.

Following the anti-climactic “Wakarusa War,” a momentary lull descends on Kansas, with the next act on the horizon being the December 15, 1856 vote on the Topeka Constitution and the Black Exclusion clause.

Sidebar: John Brown Writes About The Wakarusa War

One figure who misses out on the action in Lawrence is the fiery abolitionist, John Brown, who moves to Kansas in October 1855 to join three of his sons in fighting on behalf of the Free Staters. Brown settles at the town of Pottawatomie Creek, some 50 miles south of Lawrence. When he learns of the pending siege, he heads toward the conflict, only to arrive after the truce is negotiated. He writes the following account of the episode to his wife and other children, still living in North Elba, New York.

OSAWATOMIE, K. T., 16th December, 1855. Sabbath evening.

DEAR WIFE AND CHILDREN, EVERY ONE: I improve the first moment since my return from the camp of volunteers who lately turned out for the defense of the town of Lawrence, in this Territory, and notwithstanding, I suppose you have learned the result before this (possibly), will give a brief account of the invasion in my own way.

About three or four weeks ago, news came that a Free-state man by the name of Dow had been murdered by a Pro-slavery man named Coleman, who had gone and given himself up for trial to Pro-slavery Gov. Shannon. This was soon followed by further news that a Free-state man (i.e. Branson)…had been seized by a Missourian, appointed Sheriff by the bogus Legislature of Kansas, upon false pretenses…and, that, while on his way to jail, in charge of the bogus Sheriff, he was rescued by some men belonging to a company near Lawrence; and that, in consequence of the rescue, Gov. Shannon had ordered out all the Pro-slavery force he could muster in the Territory, and called on Missouri for further help.

That about two thousand had collected, demanding a surrender of (Branson) and the rescuers, the destruction of several buildings and printing presses, and a giving up of the Sharpe’s rifles by the Free-state man, threatening to destroy the town with cannon with which they were provided, etc.; that about an equal number of Free-state men had turned out to resist them, and that a battle was hourly expected, or supposed to have been already fought.

These reports seemed to be well authenticated, but we could get no further account of matters, and I left… for the place where the boys were settled at evening, intending to go to Lawrence to learn the facts the next day. (Then) word came that our help was immediately wanted. On getting this news, it was at once agreed to break up at John’s camp, and take Wealthy and Johnny to Jason’s camp (some two miles off), and that all the men but Henry, Jason and Oliver should at once set off for Lawrence under arms, those three being wholly unfit for duty.

We then set about providing a little corn bread and meat, blankets, cooking utensils, running bullets, loading all our guns, pistols, etc. The five set off in the afternoon, and after a short rest in the night (which was quite dark) continued our march until after daylight next morning, when we got our breakfast, started again, and reached Lawrence in the forenoon, all of us more or less lamed by our tramp.

On reaching the place, we found that negotiations had commenced between Gov. Shannon (having a force of some fifteen or sixteen hundred men) and the principal leaders of the Free-state men, they having a force of some five hundred men at that time. These were busy night and day fortifying the town with embankments and circular earthworks up to the time of the treaty with the Governor, as an attack was constantly looked for, notwithstanding the negotiations then pending.

This state of things continued from Friday until Sunday evening. On the evening we left, a company of the invaders of from fifteen to twenty-five attacked some three or four Free-state men, mostly unarmed, killing a Mr. Barber, from Ohio, wholly unarmed. His body was afterward brought in and lay for some days in the room afterward occupied by the company to which I belonged (it being organized after we reached Lawrence). The building was a large, unfinished stone hotel, in which a great part of the volunteers were quartered, and who witnessed the scene of bringing in the wife and friends of the murdered man. I will only say of this scene that it was heart rending, and calculated to exasperate the men exceedingly, and one of the sure results of civil war.

After frequently calling on the leaders of the Free-state men to come and have an interview… Gov. Shannon …signified his wish to come into the town, and an escort was sent to the invaders’ camp to conduct him in. When there, the leading Free-state men, finding out his weakness, frailty and consciousness of the awkward circumstances into which he had really got himself, took advantage of his cowardice and folly, and by means of that and the free use of whisky and some trickery succeeded in getting a written arrangement with him, much to their own liking.

He stipulated with them to order the Pro-slavery men of Kansas home, and to proclaim to the Missouri invaders that they must quit the Territory without delay, and also give up Gen. Pomeroy, a prisoner in their camp, which was all done; he also recognized the volunteers as the militia of Kansas, and empowered their officers to call them out whenever, in their discretion, the safety of Lawrence or other portions of the Territory might require it to be done.

He, Gov. Shannon, gave up all pretension of further attempt to enforce the enactments of the bogus Legislature and retired, subject to the derision and scoffs of the Free state men (into whose hands he had committed the welfare and protection of Kansas), and to the pity of some and the curses of others of the invading force. So ended this last Kansas invasion, the Missourians returning with flying colors after incurring heavy expenses, suffering great exposure, hardships and privations, not having fought any battles, burned or destroyed any infant towns or Abolition presses, leaving the Free-state men organized and armed, and in full possession of the Territory, not having fulfilled any of all their dreadful threatenings, except to murder one unarmed man, and to commit some robberies and waste of property upon defenseless families unfortunately in their power.

…But enough of this, as we intend to send you a paper giving a fuller account of the affair. We have cause for gratitude that we all returned safe and well, with the exception of hard colds, and found those left behind rather improving….Henry and Oliver, and I may say, Jason, were disappointed in not being able to go to the war. The disposition of both our camps to turn out was uniform. * * * * May God abundantly bless you all and make you faithful.

Your affectionate husband and father,

JOHN BROWN.