Section #12 - Southerners are alarmed by an apparent Northern wish to ban all blacks from the new West

Chapter 140: The Two Major Parties Select Their Candidates For The 1848 Race

May 22, 1848

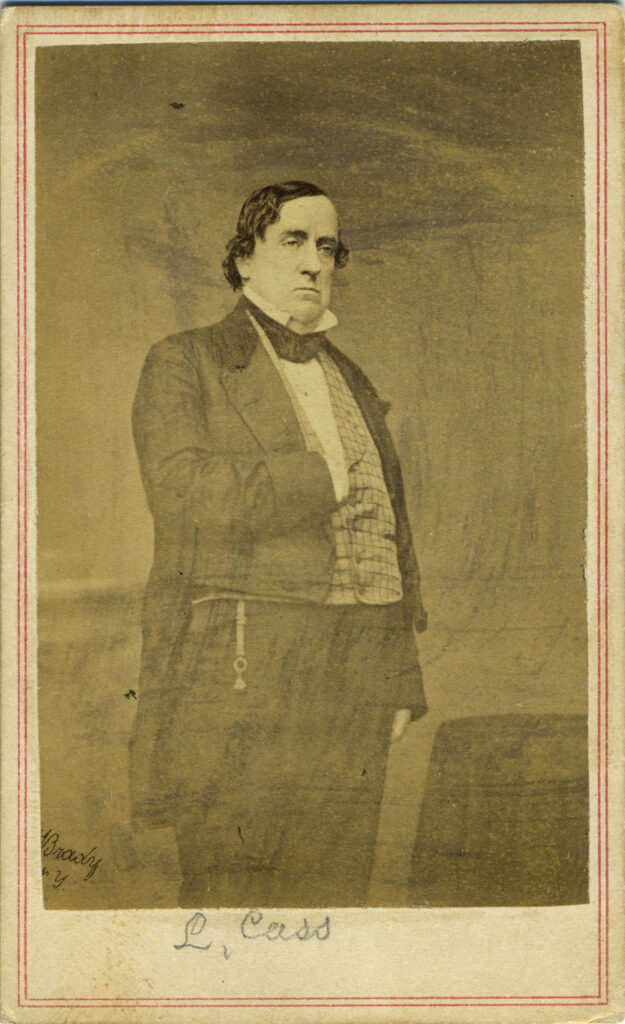

The Democrats Nominate Cass

On May 22, 1848, ten weeks after the Mexican War Treaty is signed, the Democrats convene in Baltimore to pick a presidential nominee to secede Polk, who keeps his promise of serving only one term.

Delegates from all 30 states are present, with the total count evenly split between northerners and southerners.

As expected, the issue of “slavery in the new western territories” is front and center for all.

Its divisive character is evident right away in a floor fight over seating the New York delegation, with both the Barnburners and the Hunkers claiming to represent the state. After heated debate, the convention decides, by a margin of 126-125, on a compromise, with each faction awarded 18 votes.

This results in the first “walk-out,” with the Barnburners exiting the convention to explore an alliance with other “free soil” groups, across parties, who oppose the spread of slavery.

The second walk-out occurs after Fire-Eater William Yancey presents the “Alabama Platform” proposals to the delegates, and they are voted down by a wide 216-36 margin. In protest, the hot-tempered Yancey leaves the hall.

As the actual balloting begins, it’s clear that no Southern dark horse, like Polk in 1844, will win the day.

Instead, three Northerners are in the running.

One is Supreme Court Justice, Levi Woodbury, ex-Senator and Governor of New Hampshire, and a solid Jackson man. His cause, however, is hurt by his role as Secretary of the Treasury during the Bank Panic of 1837 and the following recession.

A second contender is Polk’s Secretary of State, James Buchanan, of Pennsylvania, who received a trickle of votes in the 1844 convention. The President comes to regard Buchanan as self serving, untrustworthy and lacking in good judgment. His handling of the Oregon dispute almost leads to war with Britain; he tries to torpedo Scott’s plan to conquer Mexico City; and he plays politics with the final peace treaty, attempting to hide his early vocal opposition to acquiring any new land from the war. Despite these gaffes, Buchanan’s “resume” is sufficient for him to make a second run at the nomination.

As in 1844, however, the early front runner is again Senator from Michigan, Lewis Cass.

The 68 year old Cass is first off a tried and true Democrat, who has served in Jackson’s cabinet, consistently backs Polk, favors annexing all of Mexico, and never wavers on the rights of slave owners. On top of that, he is known forever as “General Cass,” conqueror of Tecumseh and “hero of the War of 1812” – a legacy the party hopes will allow him to offset the popular appeal enjoyed by the potential Whig military candidates, Taylor and Scott.

The voting favors Cass from the start, and he wins handily on the fourth ballot.

Voting For Democratic Party Nomination

| Candidate | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Lewis Cass | 125 | 133 | 156 | 179 |

| Levi Woodbury | 53 | 56 | 53 | 38 |

| James Buchanan | 55 | 54 | 39 | 33 |

| John Calhoun | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Others | 9 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

| Abstaining | 39 | 38 | 37 | 35 |

His running mate will be General William O. Butler, whose military career has spanned the War of 1812 through the Mexican War, where he is second in command to Taylor and wounded at the Battle of Monterrey. Butler is from Kentucky and has served two terms in the U.S. House (1839-43) before joining Cass on the ticket.

In the end, the nomination of Cass from Michigan is symbolic of what becomes the Democrat’s search for a North-South presidential compromise — something that will be repeated in 1852 with Franklin Pearce and in 1856 with James Buchanan.

All are Northern men who embrace Southern sympathies in their drive to win the presidency.

Over time they will all share the same epithet in the Northern press, that of “Doughfaces” – men lacking in firm principles, as pliable as bread dough when it comes to standing up to the South on tough issues like slavery.

1848

The Whigs Face Opportunities And Challenges Going Into 1848

The Whigs are once again optimistic as they look ahead to the 1848 election, while still having internal policy issues on slavery needing resolution.

As a party, they have added 37 House seats to their side in 1846, giving them a slim 116-112 majority. Twenty of these pick-ups come from New York and Pennsylvania, where the Wilmot Proviso garners widespread public support.

But Wilmot’s proposed ban is a two-edged sword, even for the Whigs, where 17 of their 19 Southern House members vote “no” on August 8, 1846, when it is attached to Polk’s initial Appropriations Bill.

The strategic question for the Whigs is therefore how to leverage the popularity of the Wilmot ban in the North without alienating their membership in the South.

One advantage they have over the Democrats is that much of their party strength lies in the upper South rather than in the hard-core cotton belt. The Border states of Kentucky, Maryland and Delaware, together with Tennessee, account for 7 of their 21 senators, and 16 representatives. The old South states of North Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia add 3 more in the Senate and 16 in the House.

What these Whig-heavy states have in a common is a less cotton/slave-centric economy, a long-standing commitment to the Union, and a conservative hesitancy toward any talk of secession.

The Southern Whigs also boast many established congressional leaders — men like Senators John J. Crittenden of Kentucky, John Clayton of Delaware, Reverdy Johnson of Maryland, and John Bell of Tennessee – who share personal reservations about slavery and do their best to moderate threats from the emerging Southern “Fire-Eaters.”

In the House they are joined by the likes of the Virginians, John Minor Botts and William Preston, Daniel Barringer and George Badger of North Carolina, and two exceptional Georgia Whigs, Alexander Stephens and Robert Toombs, who will persevere through many ups and downs in search of compromises to protect the Union.

Southern States Where Whigs Have Strengths In 1848

| Border | House | Senate | “Influentials” |

| Kentucky | 6 | 2 | JJ Crittenden, Charles Morehead |

| Maryland | 4 | 2 | Reverdy Johnson, James Pearce |

| Delaware | 1 | 2 | John Clayton |

| Southeast | |||

| North Carolina | 6 | 2 | Daniel Barringer, George Badger |

| Georgia | 4 | 1 | Alex Stephens, Robert Toombs |

| Virginia | 6 | 0 | John Minor Botts, William Preston |

| Southwest | |||

| Tennessee | 5 | 1 | John Bell |

| Alabama | 2 | 0 | |

| Louisiana | 1 | 1 |

June 7, 1848

The Whigs Meet In Philadelphia To Choose A Nominee

Two weeks after the Democrats nominate Lewis Cass, Philadelphia hosts its first national convention, as the Whigs pour into the “Chinese Museum” venue on Ninth Street, so-called for its historical display of eastern artifacts.

What’s on the mind of the delegates is finally electing a President who will put into practice the “American System” principles that Henry Clay laid out some twenty years ago.

They come close in 1840, until General Harrison, “Old Tippecanoe,” dies one month after his inauguration, only to be replaced by the “turncoat” Tyler, at heart a thoroughgoing Virginia Democrat. Their disappointment is repeated in 1844, when Clay, making his third run, loses a tight race to Polk.

But circumstances in 1848 appear much more hopeful. Unity within the Democratic Party has been severely tested by the Wilmot controversy, and the sitting president, Polk, has given way to a less formidable foe in Cass. Victory should be in store, if the party can nominate the right candidate.

With Clay’s influence waning, the two leading strategists for the Whigs are Kentucky Senator John Crittenden, and journalist, Thurlow Weed, who controls party politics in New York. In 1830 Weed launched the Anti-Mason Party to bring down Andrew Jackson, and his drive to unseat the Democrats remains undiminished. Together the two men will play the kingmaker role at the convention.

Crittenden himself is regarded by many as a possible candidate, but he dismisses the idea. Clay remains a favorite, but lacks momentum after prior defeats. Senator John Clayton sparks interest, but his tiny home state of Delaware works against him. A few back Supreme Court Justice John McLean of Ohio, while Webster’s decision to remain in Tyler’s administration eliminates him.

This leaves two men in the spotlight – the recent war heroes, Generals Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor.

The Democrats fear Scott more than Taylor, and Polk acts to diminish his reputation and deprive him of getting the nomination. He does so by initiating a “court of inquiry,” charging that Scott “compromised military operations” in Mexico by dealing directly with Santa Anna to end the war. Future war heroes such as Robert E. Lee and George McClellan decry Polk’s cynical ploy and Scott is acquitted – but not before the Whig convention is over.

All eyes then turn to Zachary Taylor – still a very uncertain candidate in the months leading up to the convention.

June 7, 1848

Taylor Is Chosen On The Fourth Ballot

Two questions have surrounded Taylor from the beginning: does he want to be President and is he really a Whig?

His own words, recorded soon after his February 1847 victory at Buena Vista, seem to rule out a run.

On the subject of the presidency…under no circumstances have I any aspirations for the office, nor do I have the vanity to consider myself qualified.

In fact, since departing Mexico in November 1847, Taylor has been happily retired at Cypress Grove Plantation, one of several he owns around Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He lives modestly in a small cottage, spending his days mixing easily with townspeople and overseeing the labor of his slaves, which number over one hundred.

When asked about politics, he claims that he is an Independent, not a Whig, and admits that he has never voted before in an election.

Despite these “limitations,” Thurlow Weed is certain that Taylor will win, if nominated. Like Harrison, he is a military hero, a southerner, a slave holder, and one who believes in the sanctity of the Union. Moreover, he arrives on stage with no political baggage, no public positions on controversial issues like the Wilmot Proviso, and nothing liable to offend one side or the other.

Still Weed recognizes that Taylor must publicly embrace the Whig Party prior to the Philadelphia convention.

He communicates this to Colonel William Bliss, a military aide to the General, who sends a contingent to Baton Rouge in late April 1848 to extract the needed pledge. It comes in the form of what could only be characterized as a tepid commitment:

I reiterate what I have often said…I am a Whig but not an ultra Whig. If elected I would not be the president of a party (but) would endeavor to act independent of party domination and should feel bound to administer the Government untrammeled by party schemes.

Along with a promise to insure a strong banking system, this is enough for Weed and Crittenden to proceed, and they rally a diverse band of supporters for Taylor. Included here are seven congressmen known as the “Young Indians,” including Abraham Lincoln and two Georgians, Robert Toombs and Alexander Stephens. Endorsements also appear from non-Whigs, the General’s son-in-law, Jefferson Davis, a Democrat, and the leader of the Nativist American Party, Lewis Levin. Even Scott writes glowingly about Taylor in a September 16 note to one D.F. Miller:

I know General Taylor to be one of the best citizens in our land. In point of integrity he can have no superior. His firmness of purpose is equally remarkable, and I consider him a man of excellent sense and sound judgement. He has always been known as a republican in principles and manners….

Crittenden serves as Taylor’s floor manager on June 7 and steers his way through a variety of de railers: a motion to force the nominee to obey the party platform; a denunciation from a Massachusetts delegate that the General would “continue the rule of slavery for four more years;” and the demand by backers of other candidates to register their preferences in the early balloting.

In the end, Taylor leads from the first vote forward. Clay is shown the respect he deserves before his support drifts to the two generals. On the fourth reckoning, Taylor goes over the top.

Whig Nomination For President – 1848

| Candidate | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Taylor | 111 | 118 | 133 | 171 |

| Clay | 97 | 86 | 74 | 32 |

| Scott | 43 | 49 | 54 | 63 |

| Webster | 22 | 22 | 17 | 14 |

| Clayton | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| McLean | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

June 7, 1848

Millard Fillmore Is The Nominee For Vice President

With Taylor heading the ticket, the Whigs turn to selecting a running mate.

They have learned from the John Tyler fiasco of 1840 that their choice needs to be certifiably Whiggish in regard to his political beliefs and history – a litmus test that is doubly true this time given uncertainties surrounding Taylor.

Out of fourteen names teed up at the convention, four are given serious consideration – two New Yorkers, ex-Governor William Seward and State Comptroller, Millard Fillmore; the textile tycoon from Massachusetts, Abbot Lawrence; and former Treasury Secretary under Harrison/Tyler, Thomas Ewing of Ohio.

Ewing is supremely qualified, but is eliminated by a dirty trick in the form of a false assertion on the floor that he wants his name withdrawn from consideration.

Thurlow Weed is forever firmly behind Seward, with both regarding Fillmore as a serious threat to their control over New York state politics. Seward also opposes much of what Fillmore has come to represent: lukewarm opposition to slavery, fierce anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant attacks, and a lack of curiosity, depth and decisiveness regarding national affairs.

At the same time, the energetic Seward has relatively little interest in serving as Vice-President and, along with Weed, throws his support behind Lawrence.

Lawrence, however, faces sharp divisions within his own Massachusetts delegation. Daniel Webster never forgives him for backing Clay for the 1840 nomination, while the anti-slavery “Conscience Whigs” regard him as far too aligned with Southern cotton interests, who supply his mills.

With Ewings out by deception and Seward by intent, the race comes down to Lawrence versus Fillmore.

Fillmore has climbed out of poverty as a youth to a successful legal career, four terms in the U.S. House, the founding of Buffalo University, and his current position as Comptroller of New York, overseeing accounting practices and financial reporting for state government. He is intent on returning to the national stage, and has campaigned over a year for the Vice-Presidency.

He is also well organized at the convention, and offers the delegates a Northerner who appears to be mildly against the spread of slavery, thus balancing Polk, the Southern slave owner.

The first ballot is tight, but Fillmore pulls away on the second and wins the position he is after – along with a destiny that will surpass his wildest ambition.

Ballot Results For Vice-President

| Candidate | 1 | 2 |

| Fillmore | 115 | 173 |

| Lawrence | 109 | 87 |

| Others | 51 |