Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

Chapter 136: The Treaty Of Guadalupe Hidalgo Ends The War With Mexico

February 19 – March 10, 1848

A Negotiating Breakthrough Leads To The Mexican Cession Of Southwestern Land

With political pressures mounting on Polk, good news arrives from Mexico City saying that the controversial Nicholas Trist has achieved a breakthrough on a treaty with Manuel de la Pena y Pena, the ex-Supreme Court justice named interim president after Santa Anna’s resignation.

Since arriving in Veracruz on May 6, 1846, Trist’s negotiations have violated all diplomatic norms. After Polk orders him to return home in December, he learns that Trist and General Winfield Scott are moving forward essentially on their own. The two men by now share a common disdain for Pillow, Buchanan, and Polk and a belief that they are America’s best hope for reaching a settlement of the war.

Unlike the strident Santa Anna, Pena y Pena is eager to resolve the conflict, assuming it allows Mexico to retain its standing as an independent nation. Trist knows that Polk supports this outcome, and so the talks, at the town of Guadalupe Hidalgo outside Mexico City, focus on drawing territorial boundaries in the north and agreeing on a cash payment.

Trist walks a fine line with Polk’s instructions here. He agrees to a border that is slightly farther north than Polk wants, both in Arizona and in Alta (upper) California, while still insisting on control over the important port city of San Diego. At the same time he convinces the Mexicans to accept $15 million for the land, well under the $30 million Polk sets as a maximum.

On February 2, 1848, Trist and Pena y Pena sign the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and send it off hoping for final approval in Washington. Polk receives a copy on February 19, and finds the terms acceptable, despite his ongoing anger over Trist’s rogue methods. The next day, he forwards it to the Senate.

As expected, the treaty becomes a political football, with both the Democrats and Whigs trying to stake out their positions on the war and the treaty in advance of the 1848 presidential race.

On February 23, news that ex-President John Quincy Adams has died, following a sudden collapse on the floor of the House, momentarily mutes the contentiousness. After a hiatus to honor Adams, the Trist Treaty is finally approved in the Senate on March 10 by a vote of 38-14.

With the Mexican Cession in place, America has both extended and secured, once and for all, its borders, and its recognition as one of the world’s most powerful nations.

But the victory comes with a “poison pill” that will haunt and divide the nation going forward: whether or not slavery will be allowed to take hold in the Mexican Cession land just acquired. This is the exact issue that kept Andrew Jackson and other Presidents before Polk from prior invasions in the west.

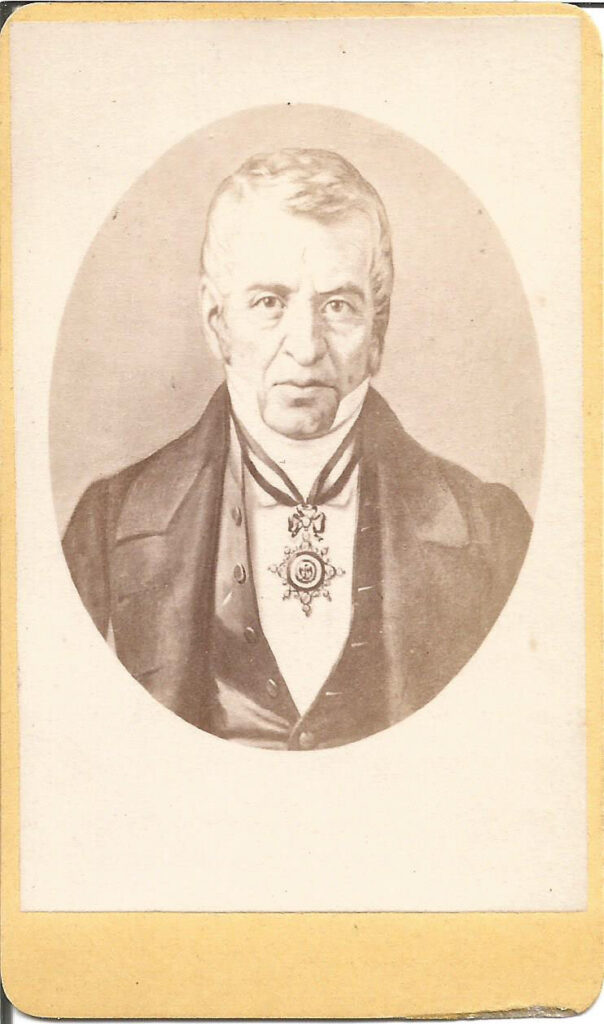

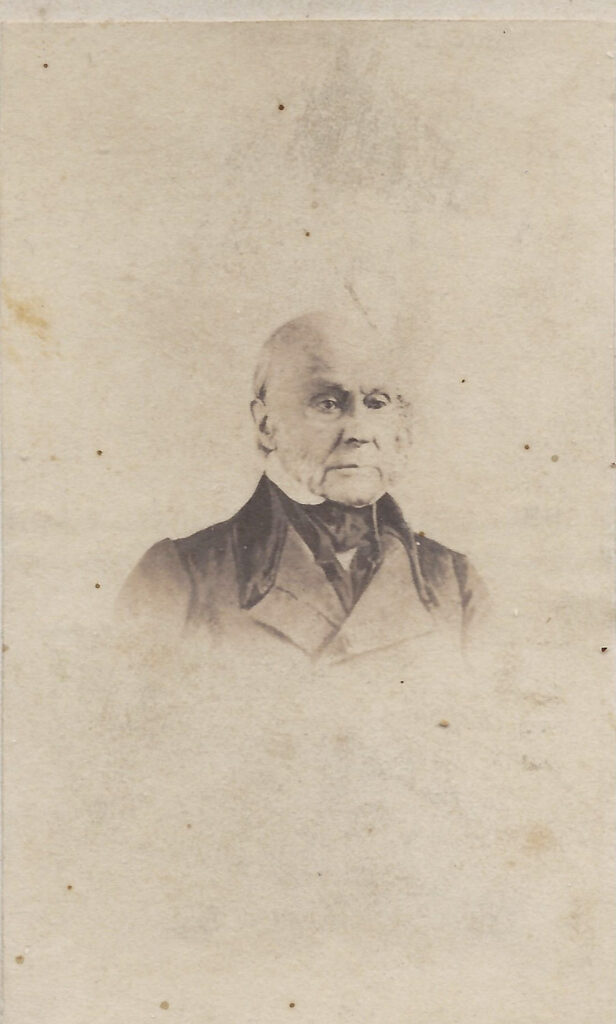

Sidebar: Death Of The Remarkable John Quincy Adams

No Whig has been more strongly opposed to the aggressive war against Mexico or more supportive of Wilmot’s ban on expanding slavery than John Quincy Adams.

In February 1848, the 80-year-old ex-President, is serving his eighth term in the House. His bete noir, Andrew Jackson, a man Adams regards as a “murderer, adulterer, and slanderer,” has died three years earlier.

In November 1846 he suffers a slight stroke that impairs his right side for several months and leaves him frail upon his return to the second session of the 30th Congress. Still his compelling sense of duty has him back on the floor on February 21, 1848, registering his final opposition to the war, when he topples over, into the arms of his colleagues.

Two days later, on February 23, dies in the Capitol building. He is survived by Louisa, his London born wife of fifty years, and by one of the couple’s children, Charles Francis Adams, who follows in his father’s diplomatic and political footsteps.

In the end, JQ Adams has spent his entire life trying to live up to the “good son and public servant” dictates of his iron-willed parents, John and Abigail Adams.

As a small boy he witnesses the American Revolution. In 1781, when he is fourteen, his father sends him on his first diplomatic journey to Russia. His life has never been easy, but he sums it up well in his own words:

With regard to what is called the wheel of Fortune, my career in life has been, with severe vicissitudes, on the whole highly auspicious.

Public Service Record Of JQ Adams

| Dates | Age | Office |

| 1781 – 1784 | 14-17 | Assistant to US Minister to Russia |

| 1794 – 1797 | 27-30 | Minister to the Netherlands |

| 1797 – 1801 | 30-34 | Minister to Prussia |

| 1803 – 1808 | 36-41 | U.S. Senator from Massachusetts |

| 1809 – 1814 | 42-47 | Minister to Russia |

| 1814 – 1817 | 47-50 | Ambassador to Britain |

| 1817 – 1825 | 50-58 | Secretary of State (Monroe) |

| 1825 – 1829 | 58-62 | President of the United States |

| 1831 – 1848 | 64-80 | U.S. House of Representatives |