Section #20 - Futile attempts to save the Union follow John Brown’s Raid at Harpers Ferry

Chapter 243: The South Responds To The Harpers Ferry Raid

October 1859 Forward

Reprisals Take Place Across The South

Shock waves reverberate across the South even after John Brown is in his grave.

The event itself is sui generis. It goes well beyond the 1831 rebellion by Nat Turner, in that the leader here is a white man, not a black, and a Northerner to boot. As such it feels like a betrayal of the basic trust between the states and sections that allowed the Union to form in the first place.

In the South, Brown symbolizes that worst nightmare for a civilized society, a homegrown terrorist – and they respond to the fear he has triggered in predictable fashion. First they try to search out and punish the perpetrators, and then to tighten their local security to prevent future attacks.

As usual, the easiest target for punishment are the blacks in their presence — and any whose prior behavior suggests a threat are subject to beatings, lynchings and even burning at the stake. The extent of the retributions here is unknown, but it likely matches or exceeds those following the Nat Turner uprising.

But this time the spotlight even extends to the 353,000 free blacks living across the South alongside its 3.9 million slaves. The state of Maryland asks whether it is time to put an end to “free negroism.” North Carolina follows up by passing legislation whereby all free blacks are given a choice between becoming “re-enslaved” or leaving the state. Mississippi and Arkansas eventually do the same.

Attention also falls on suspected “white collaborators.”

These include anyone thought to be harboring anti-slavery sentiments. As rumors spread, “Black Lists” materialize from town to town, along with local boycotts of any businesses run by “negro sympathizers.”

Attempts are also made to interdict publications and other materials from the North that are deemed to be critical of slavery. Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune becomes a leading example, along with the Springfield Republican and Harpers Weekly Magazine.

The intent of these moves is well articulated by an editorial in the Atlanta Confederacy:

We regard every man in our midst an enemy to the institutions of the South who does not boldly declare that he believes African slavery to be a social, moral, and political blessing. If not he should be requested to leave the country!

Along with the above, efforts are made to strengthen the response time and effectiveness of local militias to deal with any future crises. The scenario that has played out at Harpers Ferry is an embarrassment for the South. The strategic targets – the bridge, the Arsenal and Armory, and the Rifle Works – fall without resistance. The local response to the raid is poorly led and uncoordinated, more of a mob scene than anything else. President Buchanan is slow to call out federal support, and more than a full day passes before Robert E. Lee and his marines show up.

All of this becomes a wake-up call for both the local, state and federal militia in the South. The result are growing enlistments and greater preparation in case force is required again in the future.

October 1859 Forward

Edmund Ruffin Exploits Harpers Ferry To Sell Secession

While retribution and defensive measures are on the minds of most Southerners, a smaller contingent is eager to exploit Harpers Ferry to promote their own agenda – that being secession.

This notion of exiting the Union has a long history in America, especially in the state of South Carolina, where John Calhoun tries for decades to alert the region to the threats it faces from the North – especially as the balance of power in Congress slips away.

When Calhoun dies in 1850, leadership passes on to the next generation of proponents labeled the Fire-eaters. Included here are men like James Henry Hammond of South Carolina, William Yancey of Alabama, and Louis Wigfall of Texas.

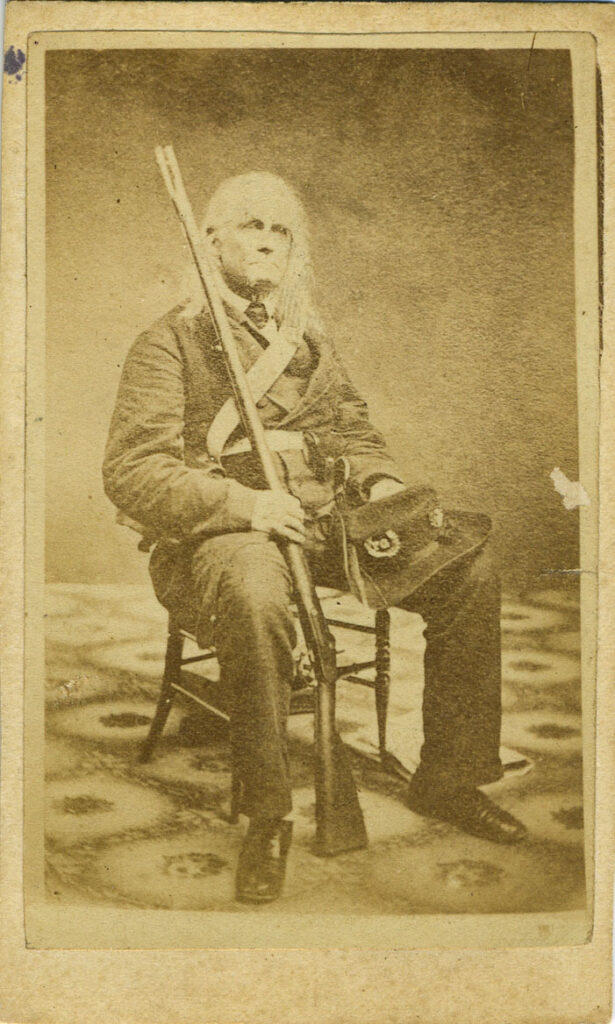

But one man who stands out after Harpers Ferry is sixty-five year old Edmund Ruffin, born into the Virginia planter aristocracy and initially famous for his pioneering scientific work on preventing soil erosion through rotating crops and spreading “marlstone” (lime-rich mud) on his tobacco fields. He is also a member of the Southern intellectual class, along with William Simms, Beverly Tucker and James Hammond.

Like the others, Ruffin believes that “slavery as a positive good,” and carries this so far as to suggest that the US might colonize Africa to provide the natives with a path to Christian salvation.

Instead of a tragedy, he regards Harpers Ferry as a fortuitous alarm regarding abolitionist threats:

Finally proof arrived out of the blue…Such a practical exercise of abolitionist principles is needed to stir the sluggish blood of the South.

The Enquirer of Richmond shares his read on the importance of the event:

The Harpers Ferry invasion has advanced the cause of disunion more than any other event that has happened since the formation of the nation.

The villains, Ruffin claims, are not simply the twenty-two raiders, but the entire Northern population.

Southerners at last has an identifiable, common for, the great majority of the Northern people.

The result of the raid will finally force the South to choose secession over submission.

I wish for the Southern states to be forced to choose between secession and submission to abolitionist domination.

October 1859 Forward

Southerners Expect Northern Condemnation Of The Terrorist Attack

To dramatize his message, Ruffin is able to lay his hands on fifteen of “John Brown’s Pikes,” in addition to the one that he carries around personally in public. These pike are savage looking weapons, eight foot long spears, topped by a Bowie knife, to be wielded by the liberated slaves as pay-back to their masters.

Ruffin intends to make them as memorable as the cane Preston Brooks has used to thrash Charles Sumner into submission in the Senate in 1856. He does so by packaging each pike up in a special display case with an enclosed message:

A sample of the favors designed for us by our Northern brethren.

He then sends one to each of the sitting Governors in the slave states, with the exception of Delaware, where he sees no hope of provoking the response he wants. Instead the fifteenth pike goes to the state capitol in Charleston, where he is certain of a favorable reception.

This effort by Ruffin becomes one aspect of the Fire-eater’s secession campaign leading into the fast approaching presidential campaign of 1860.

Its goal is to convince Southerners that the raid was not the isolated work of a madman, but rather to connect the dots between John Brown and the Black Republican Party, with its abolitionist inspired intent to do away with the institution of slavery.

Ruffin even declares that he hopes for a Republican victory in 1860 since that will…

Agitate and exasperate the already highly excited indignation of the South.

To further drive home his call for immediate secession, he challenges his fellow Southerners to watch the reactions to the Harpers Ferry raid among their fellow citizens in the North.

Will they condemn it outright or somehow find ways to justify it? For many Southerners this question seems to become a litmus test related to the possibility of leaving the Union.

June 7, 1865

Sidebar: Edmund Ruffin

Ruffin Chooses Suicide Over Capitulation

On April 12, 1861 he is at Cummings Point on the tip of Morris Island, just two miles southeast of Ft. Sumter, serving as a member of the Palmetto Guards. According to myth he is given the honor there of firing the first cannon shot of the war, and then becoming the first man to enter the fallen fort. Two of his sons serve in the CSA army, but, owing to his advanced age, his service during the conflict is limited to visiting and rallying troops in the field.

The final surrender at Appomattox finds Ruffin in despair. He wife is long gone and only two of his ten children remain alive. His plantations have has been overrun and looted by Union troops, who also burn his precious books and collection of fossil shells.

On June 17, 1865, at his son’s Redmoor home, Ruffin goes to his room and writes a final entry in his diary, before wrapping a Confederate flag around his shoulders and killing himself with a shotgun. This act mirrors that of his godfather, Thomas Cocke, in 1840. His last recorded words signal his undying hatred for the Yankees:

And now with my latest writing and utterance, and with what will [be] near to my latest breath, I here repeat, & would willingly proclaim, my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule—to all political, social and business connections with Yankees, & to the perfidious, malignant, & vile Yankee race.