Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

Chapter 82: The South Intensifies Its Defense Of Slavery

1820-1836

Anxiety Mounts Over The North’s Anti-Slavery Intrusions

Ever since the 1820 controversy over admitting Missouri as a slave state, Southerners have feared that the North will indeed act against the “peculiar institution” that serves as the basis for their regional prosperity.

The threat level increases during the Second Great Awakening of the 1820’s when calls to action by the Evangelical preacher, Reverend Charles Finney, produce a host of white abolitionist reformers from Lloyd Garrison to Theodore Weld, Arthur and Lewis Tappan, Lucretia Mott, Angelina Grimke, Gerrit Smith, and James Birney.

Garrison’s 1831 Liberator newspaper provides early publicity for the movement, gives voice to pleas for freedom from blacks like David Walker, and attempts to shame the public and the politicians into amending the broken 1787 Constitution. As Garrison proclaims:

That which is not just is not law.

Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion demonstrates what can happen when slaves take the law into their own hands and seek retribution against their white masters. But this fails to slow down the reformers.

Even the presidency of lifelong planter and slave-holder Andrew Jackson fails to produce the kind of affirmative support for the “interests of the South” that was anticipated. When South Carolina signals its intent, as a sovereign state, to nullify the Tariff of Abominations, Jackson signals his intent to send US troops in to enforce federal law.

He then dumps the leading Southern advocate, John C. Calhoun, off his ticket in 1832, in favor of a Northern man, Martin Van Buren.

In 1833 the American Anti-Slavery Society organizes chapters across the North who gather abolitionist petitions and send them to congress to be read on the floor of the House.

When this form of agitation becomes visible in Washington, Southern politicians react by passing the 1836 “Gag Rule” to try to shut down public debate. But ex-President John Quincy Adams refuses to comply and the result is even more heated rhetoric.

The Northern men in Congress by no means favor abolition, but they also do not appreciate being maneuvered by Southerners – especially now that the population count in “their region” gives them majority voting power in the House.

And then in 1837, the new President from New York feels called upon to openly mention the heretofore taboo subject of slavery in his inaugural address to the nation.

All this adds up to a fear that has endured across the South since the founders met in Philadelphia – a fear that, at some moment, the North will turn the power of the federal government against the institution of slavery, the fragile foundation of the region’s wealth.

February 6, 1837

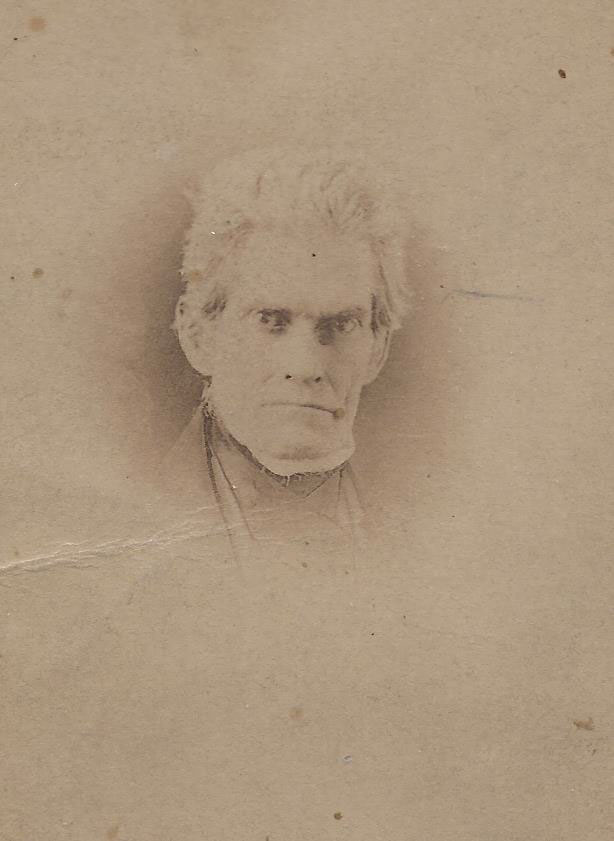

John Calhoun Argues The “Slavery Is A Positive Good”

It is, of course, John C. Calhoun, who consistently tries to alert the South to the imminent dangers of a federal government intruding on the business of slavery.

On February 6, 1837, with his tenure as Vice-President and his prospects for the White House over, he rises on the Senate floor to deliver what will become known as his “slavery is a positive good” speech.” For the sake of drama, he begins by reading two anti-slavery petitions to his colleagues, then proceeds to counter with his own analyses.

I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin, and distinguished by color, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two, is, instead of an evil, a good–a positive good.

Instead of abusing the Africans, slavery has actually enlightened and elevated them.

I appeal to facts. Never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually.

How much better off is the Southern slave than the pauper classes of society at large.

I may say with truth, that in few countries so much is left to the share of the laborer, and so little exacted from him, or where there is more kind attention paid to him in sickness or infirmities of age. Compare his condition with the tenants of the poor houses in the more civilized portions of Europe–look at the sick, and the old and infirm slave, on one hand, in the midst of his family and friends, under the kind superintending care of his master and mistress, and compare it with the forlorn and wretched condition of the pauper in the poorhouse.

Furthermore, the practice of slavery has always been part and parcel of sustaining a prosperous society.

I hold then, that there never has yet existed a wealthy and civilized society in which one portion of the community did not, in point of fact, live on the labor of the other.

The lion’s share of all wealth has always gone to those who have risen above the producing classes.

Broad and general as is this assertion, it is fully borne out by history. This is not the proper occasion, but, if it were, it would not be difficult to trace the various devices by which the wealth of all civilized communities has been so unequally divided, and to show by what means so small a share has been allotted to those by whose labor it was produced, and so large a share given to the non-producing classes.

The South has relied on a simple patriarchal approach to extract wealth from its slave class.

The devices (to extract wealth) are almost innumerable, from the brute force and gross superstition of ancient times, to the subtle and artful fiscal contrivances of modern. I might well challenge a comparison between them and the more direct, simple, and patriarchal mode by which the labor of the African race is, among us, commanded by the European.

Because of slavery, the South actually avoids the conflict between labor and capital seen in the North.

There is and always has been in an advanced stage of wealth and civilization, a conflict between labor and capital. The condition of society in the South exempts us from the disorders and dangers resulting from this conflict; and which explains why it is that the political condition of the slaveholding States has been so much more stable and quiet than that of the North.

Preserving slavery is the best path for America to sustain stable political institutions.

I turn to the political; and here I fearlessly assert that the existing relation between the two races in the South, against which these blind fanatics are waging war, forms the most solid and durable foundation on which to rear free and stable political institutions.

Attempts to abolish slavery will end the union between the South and the North.

Abolition and the Union cannot coexist. As the friend of the Union I openly proclaim it. We of the South will not, cannot, surrender our institutions. Maintain(ing) the existing relations between the two races is indispensable to the peace and happiness of both. It cannot be subverted.

The South has the means to defend itself, but only if it awakens to the threats in time.

Surrounded as the slaveholding States are with such imminent perils, I rejoice to think that our means of defense are ample, if we shall prove to have the intelligence and spirit to see and apply them before it is too late. (But) I fear it is beyond the power of mortal voice to awaken it in time from the fatal security into which it has fallen.

Thankfully the dangers can still be avoided if political concert can be achieved.

All we want is concert, to lay aside all party differences and unite with zeal and energy in repelling approaching dangers. Let there be concert of action, and we shall find ample means of security without resorting to secession or disunion. I speak with full knowledge and a thorough examination of the subject, and for one see my way clearly.

This 1837 address by Calhoun will stand the test of time as the clearest declaration of how the plantation aristocrats of the South view the institution of slavery and rationalize it to themselves. Civilization has always been run and advanced by the superior few, operating off the daily labor of the producing masses – be they better off African slaves in Southern cotton fields or worse off wage slaves in Northern factories. This is the way it is – and the way it must remain. So says the Senator from South Carolina on behalf of his colleagues.