Section #20 - Futile attempts to save the Union follow John Brown’s Raid at Harpers Ferry

Chapter 248: The South Demands A Congressional Act Sanctioning Slavery

January 1860

Southerners Stall All Legislative Progress

Legislative activity in the 36th Congress proves every bit as contentious as the election of a Speaker, with the Republicans lacking enough power to accomplish their agenda, and the Democrats continuing to splinter along sectional lines.

A new Homestead Act, granting 160 acres of federal land in the territories free of charge to settlers, passes both chambers, but is vetoed by Buchanan. The acreage is far too small to accommodate plantations and the South fears that it will only attract more small farmers who oppose competition from slaves.

The Republicans drive a protective tariff through the House, but it is blocked in the Senate. Infrastructure projects on the intercontinental railroad and Great Lakes navigation meet the same fate.

Taken together Northerners conclude that the South intends to impede all forms of progress until it gets its way on the expansion of slavery.

A bill is even introduced to re-open the international slave trade, banned as of 1808 by the 1787 Constitution. This is strictly a cynical move by Southern fire-eaters to force more contentious debate on their assertion that “slavery is a positive good.” It goes nowhere, and even irritates Upper South states like Virginia and North Carolina, who want to profit by selling their own “excess slaves,” not increase the supply and lower the prices through imports.

Further threats of Southern secession only add to the animus. Congressman Lawrence Keitt says he is ready to “shatter this Republic from turret to foundation stone.” Governor William Gist, also of South Carolina, adds his voice:

I am prepared to wade in blood rather than submit to inequality and degradation.

(Keitt will subsequently be killed in action at the Battle of Cold Harbor on June 2, 1864.)

But instead of buckling to these threats, they only serve to stiffen the backbone of the Republicans.

February 2, 1860

Jefferson Davis Announces The South’s Demand

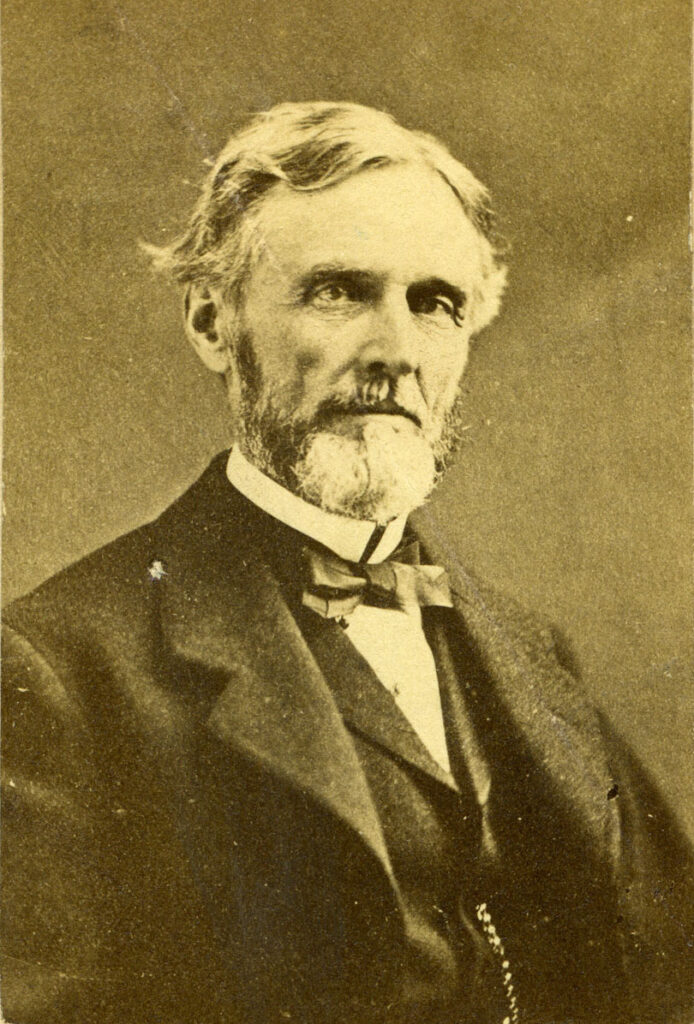

Finally, on February 2, 1860, the Southern demands on slavery are put forth by Jefferson Davis of Mississippi.

He is 51 years old, a West Point graduate, son-in-law of Zachary Taylor and valorous Colonel, wounded during the US victory at the Battle of Buena Vista. He leaves the military for good in 1847 when Mississippi Governor Albert Brown selects him to fill a vacant Senate seat. He then serves as Secretary of War under Pierce, before returning to the upper chamber in 1857. He believes in a slave society, but also fears that the North will not allow the South to secede peacefully, and that his region lacks the military might to prevail in a war.

What he wants instead is an unequivocal federal guarantee, backed by Congress, to protect the practice of slavery in territories before they apply for statehood, and after, if that becomes the will of the residents. As he says:

It is the duty of the Federal Government there to afford the needful protection (of slavery), and if experience should prove that the judiciary does not possess power to insure adequate protection, it will then become the duty of Congress to supply such deficiency.

Davis’ intent here is to force his fellow Democrats to visibly reject the so-called Freeport Doctrine that Stephen Douglas announced in his second debate with Lincoln – the notion that even if Kansas became a Slave State under the Lecompton Constitution, the people could still avoid the outcome by refusing to pass local policing measures needed to achieve compliance.

But the South’s demand is rejected – mainly owing to resistance from Northern Democrats who remain committed to Douglas for President and to the historical plank of “popular sovereignty” as the proper solution on the expansion of slavery.

With this stalemate in Congress, all eyes turn to the 1860 nominating conventions.