Section #21 - A North-South Split in the Democrat Party leads to a Republican Party victory in 1860

Chapter 252: The Republicans Nominate Abraham Lincoln

May 16, 1860

The Republican Convention Opens In Chicago

Republicans are riding a wave of political optimism as they gather in Chicago on May 16, 1860 for their second national convention.

The city itself is booming, its population up to 109,000 (9th in the nation), and its unique combination of Great Lakes shipping and railroad lines is cementing its role as the hub for East West commercial traffic.

To accommodate the large crowds, a mammoth wooden convention center, christened the Wigwam, is built along the south branch of the Chicago River, on the site of the old Sauganash Hotel, the first such facility in the city. On the opening day some 12,000 people pack the new structure, with another 20,000 milling about outside the hall, enjoying the various bands, parades, entertainers, food tents and free liquor available.

A total of 466 official delegates are seated in the hall. They represent 24 of the current total of 33 states, the other nine ominously comprising Southern hold-outs (NC, SC, Ga, Fla, Ala, Miss, La, TN and TN). Each attending state’s voting power is a rough reflection of their prominence in the US Congress.

Delegate Count At Chicago

| States | # |

| NY | 70 |

| Pa | 54 |

| Ohio | 46 |

| Massachusetts | 26 |

| Indiana | 26 |

| Kentucky | 23 |

| Virginia | 23 |

| Illinois | 22 |

| Missouri | 18 |

| Md | 16 |

| Maine | 16 |

| Iowa | 16 |

| NJ | 14 |

| Conn | 12 |

| Mich | 12 |

| Texas | 10 |

| WI | 10 |

| NH | 10 |

| Vt | 10 |

| RI | 8 |

| California | 8 |

| Minnesota | 6 |

| Del | 6 |

| Oregon | 4 |

| Total | 466 |

Notable delegates include John Andrew (MA), Gideon Welles (CT), Preston King, William Evarts and George Curtis (NY), David Wilmot and Thaddeus Stevens (Pa), Francis P. Blair Sr. (Md), Thomas Spooner (Oh), Caleb Smith (Ind), David Davis and Nathan Judd (IL), Carl Schurz (WI), Francis P. Blair Jr and Gratz Brown (MO), Horace Greeley (NY) and Eli Thayer (OR).

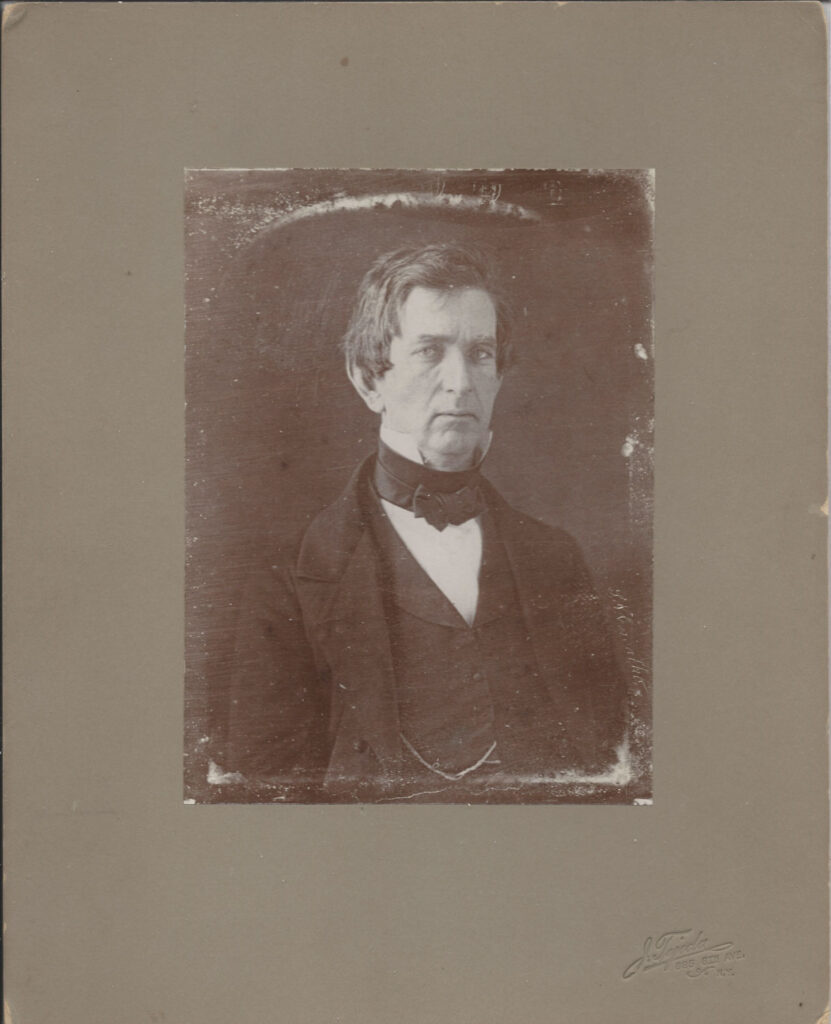

The temporary chairman of the convention is Judge David Wilmot of Pennsylvania, famous for his 1846 Proviso in the U.S. House demanding that slavery be excluded from any lands won in the Mexican War, not on moral grounds, but so that white men and free labor would prevail. Wilmot’s keynote address emphasizes the mission of the Party – to stop the Democrat’s attempt to nationalize slavery.

A great sectional and aristocratic party, or interest, has for years dominated with a high hand over the political affairs of this country. That interest has wrested, and is now wresting, all the great powers of this government to the one object of the extension and nationalization of slavery. It is our purpose, gentlemen, it is the mission of the Republican Party and the basis of its organization, to resist this policy of a sectional interest…. It is our purpose and our policy to resist these new constitutional dogmas that slavery exists by virtue of the constitution wherever the banner of the Union floats.

George Ashmun, an ex-congressman from Massachusetts is elected President of the convention and a committee is named to draft a platform.

May 17, 1860

A Platform Is Written To Win The Entire North

The paramount goal for the Republicans is to win the Presidency in 1860, and to do so they must be sure to sweep the Northern states, including the five won by Buchanan in 1856.

Northern States Won By Buchanan in 1856

| States | Electoral Votes | Buchanan % of Votes | Runner Up |

| Pennsylvania | 27 | 50% | Fremont 32% |

| Indiana | 13 | 50% | Fremont 40% |

| Illinois | 11 | 44% | Fremont 40% |

| New Jersey | 7 | 47% | Fremont 29% |

| California | 4 | 48% | Fillmore 33% |

Their primary appeal to the North lies in the promise to oppose the “nationalization of slavery” sought by the South in response to the Dred Scott ruling. This is the glue that holds the Republican coalition together, despite the internal division between the minority, who oppose slavery on moral grounds, and the majority, who would simply prefer an all-white America.

The latter group, along with potentially “switchable” Northern Democrats, want a platform that offers more than just a ban on the expansion of slavery – something that the savvy newspaperman and at-large delegate, Horace Greeley, notes:

I want to succeed this time, yet I know the country is not Anti-Slavery. It will only swallow a little Anti-Slavery in a great deal of sweetening. An Anti-Slavery man per se cannot be elected; but a Tariff, River and Harbor, Pacific Railroad, Free Homestead man may succeed although he is Anti-Slavery.

The Platform Committee shares Greeley’s assessment and writes a succinct document in seventeen articles that explain the core principles for the 1860 campaign. It accuses the Democrats of abandoning the intent of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, being co-opted by Southern demands, and, in so doing, risking disunion. It promises to end this subservience and carry out the original intent of the founders to end the spread of slavery so that it eventually withers away.

Then come to some flourishes intended to deliver the “sweetening” sought by Greeley. Article 4 tries to reassure the South about State’s rights against any threats of abolition. Article 12 offers up a protective tariff much desired in New Jersey. Article 13 supports a Homestead Act offer of 160 free acres of land to western settlers. Article 14 gently defuses Know Nothing threats to immigrants. Article 15 is aimed mainly at the Great Lakes states wishing for upgrades in ports and navigational problems. Article 16 reaffirms the intent to move ahead with the long-delayed Pacific railroad, a boon to all commercial entities.

- “The history of the nation during the last four years has…established the necessity…of the Republican Party.

- That the maintenance of the principles promulgated in the Declaration of Independence including “all men are created equal,” along with “the Federal Constitution, the Rights of the States and the Union must be preserved.

- “No Republican member of Congress has uttered…the threats of disunion so often made by Democratic members.

- “The right of each state to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively…is inviolate.

- “The Democratic Administration has far exceeded our worst apprehension in its measureless subserviency to the exactions of a sectional interest, as especially evinced in its desperate exertions to force the infamous Lecompton Constitution upon the protesting people of Kansas…”

- “The recent…developments of frauds and corruptions at the Federal metropolis show that an entire change of administration is imperatively demanded.

- “That the new dogma that the Constitution, of its own force, carries slavery into any or all of the territories of the United States, is a dangerous political heresy, at variance with the explicit provisions of that instrument itself, with contemporaneous exposition, and with legislative and judicial precedent; is revolutionary in its tendency, and subversive of the peace and harmony of the country.”

- “That the normal condition of all the territory of the United States is that of freedom: That…it becomes our duty, …to maintain this provision of the Constitution against all attempts to violate it; and we deny the authority of Congress, of a territorial legislature, or of any individuals, to give legal existence to slavery in any territory of the United States.”

- “That we brand the recent reopening of the African slave trade, under the cover of our national flag, aided by perversions of judicial power, as a crime against humanity and a burning shame to our country…”

- “That in the recent vetoes, by their Federal Governors, of the acts of the legislatures of Kansas and Nebraska, prohibiting slavery in those territories, we find a practical illustration of the boasted Democratic principle of Non-Intervention and Popular Sovereignty, embodied in the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, and a demonstration of the deception and fraud involved therein.”

- “That Kansas should, of right, be immediately admitted as a state under the Constitution recently formed and adopted by her people, and accepted by the House of Representatives.”

- Support for “duties upon imports…which secures to the workingmen liberal wages…and to mechanics and manufacturers an adequate reward for their skill, labor and enterprise….”

- That we protest against any sale or alienation to others of the public lands held by actual settlers…and we demand the passage by Congress of the complete and satisfactory homestead measure which has already passed the House.

- That the Republican party is opposed to any change in our naturalization laws…and in favor of giving a full and efficient protection to the rights of all classes of citizens, whether native or naturalized, both at home and abroad.

- That appropriations by Congress for river and harbor improvements of a national character, required for the accommodation and security of an existing commerce, are authorized…and justified…

- That a railroad to the Pacific Ocean is imperatively demanded by the interests of the whole country; that the federal government ought to render immediate and efficient aid in its construction…

- Finally…we invite the co-operation of all citizens…who substantially agree with us in their affirmance and support.

May 17, 1860

Five Candidates Vie For The Presidential Nomination

The platform is approved and on May 17 attention turns to nominating a Presidential candidate. Five men enter the convention with enough support to have a shot. They are:

Leading Candidates For President At The 1860 Republican Convention

| Name | State | Age | Currently |

| Henry Seward | NY | 59 | U.S. Senator from New York |

| Abraham Lincoln | IL | 51 | Law practice in Illinois |

| Simon Cameron | Pa | 61 | U.S. Senator from Pennsylvania |

| Salmon Chase | Oh | 52 | Recently retired Governor of Ohio |

| Edward Bates | MO | 66 | Law practice in Missouri |

The clear front-runner is the New Yorker, Henry Seward, coming to the end of his second term in the Senate after previously serving as Governor. At the 1856 convention, he was also the leading candidate, but withdrew after his long-time advisor, Thurlow Weed, convinced him that no Republican could beat Buchanan that year.

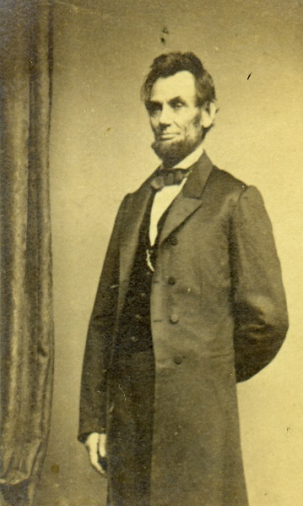

An emerging challenger to Seward is Abraham Lincoln, a contender for the Vice-Presidential candidacy in 1856, whose 1858 debates with Stephen Douglas for a Senate seat in Illinois have thrust him into the national spotlight. Lincoln enters the convention as a logical “second choice” across many different delegations.

Three other men enjoy support at a more confined, regional level.

In the crucial swing state of Pennsylvania the nod goes to sitting Senator Simon Cameron. Prior to entering politics, he becomes a wealthy businessman, first as a printer, then a railroad builder and finally a banker.

Salmon Chase is known initially for his distinguished career as a lawyer in Cincinnati, and then for playing a crucial role in founding the Liberty Party in 1843, the Free Soil Party in 1848, and the Republican Party in 1854. He has been twice elected as Governor of Ohio, retiring from that office in January 1860.

Lastly, there is the conservative ex-Whig, Edward Bates, another accomplished lawyer, whose involvement in Missouri politics dates back to 1822, and who is touted at the convention by two king-makers, Francis Preston Blair Sr. and Horace Greeley.

Eight other men will gain minor support on the first ballot, but most qualify merely as “favorite sons.”

May 17, 1860

Reservations Exist For Each Contender

Henry Seward and his campaign manager, Thurlow Weed, arrive in Chicago confident of victory. For well over a decade he has been in the national spotlight, opposing the leading Democrats in Congress and championing the ban on extending slavery to the new territories.

Despite this, many delegates are concerned about his ability to carry the lower North states, from Pennsylvania through Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa, where their mid-to-southern districts still retain some conservative and even pro-slavery sentiments. Two convention attendees who damage Seward’s chances are Andrew Curtain, about to run for Governor of Pennsylvania, and Henry Lane, doing the same in Indiana. Both spread their fear of losing should Seward head the ticket in their states.

For these men, and others, Seward is considered “too radical” for their constituents. Conservative Whigs remain shocked by his March 1850 speech opposing slavery based on a “higher law” than the Constitution. Likewise his October 1858 “irrepressible conflict” address seems to dismiss all hope that the break-up of the Union might yet be avoided.

For Horace Greeley – who appears to favor his fellow New Yorker while secretly behind Bates – Seward is the symbol of unbridled Anti-Slavery fervor that is out of touch with the majority of white voters. If he wins the nomination, the door will be left open for Democratic attacks on the “Black Republicans” as wild-eyed abolitionists, supporting negro suffrage and outrages like racial inter-marriage – the kind of opprobrium Douglas hurled at Lincoln in their 1858 debates.

Aside from Seward, the other candidates also have their vulnerabilities.

Simon Cameron is accused of shady financial practices throughout his business career, and for relying on machine politics and the spoils system while in office. His support is also thin outside of his home state of Pennsylvania.

Salmon Chase is considered more radical than Seward on the issue of slavery, and is not even certain of carrying Ohio in the general election. He possesses a brilliant legal mind and is an astute political strategist, but his manner is decidedly grave and lacking in personal wit and charm.

Edward Bates is another dour individual who suffers from extensive “baggage” despite endorsements from Blair Sr. and Greeley. He grows up on a slave plantation in Virginia; lives in the slave state of Missouri; and may or may not be willing to argue strongly on behalf of banning slavery in the territories. He never officially joins the Republican Party and his momentary membership with the Know Nothings alienates its German immigrant wing.

Finally there is Abraham Lincoln, a fresh face for a still fresh Party. But he is also an outsider to Washington politics, with only a one lackluster term in the House some twelve years ago, and back to back losses in 1854 and 1858 for a Senate seat from Illinois.

As he enters the field, Lincoln is not a dark horse, but every bit a long shot.

Summer-Fall 1860

Lincoln’s Campaign Begins Well In Advance

Lincoln’s genius as a politician is on display as he carefully positions himself to defeat Seward and win the 1860 nomination.

He has always had an easy-to-like personality, marked by a witty and self-deprecating sense of humor and an open manner that appeals to both the humble and the high and mighty. This earns him the sobriquet as “Honest Abe,” a valuable distinction within the less than trustworthy political class.

He has also proven again and again that his intellectual capacity far exceeds expectations, given his lack of formal education, his gangly appearance and dress, and his high pitched Kentucky twang. Anticipating relatively little, his audiences — be they trial juries or potential voters — are startled by his razor sharp mind and his capacity to simplify the complex and state his arguments with pristine logic and touching emotional pleas. As a speaker, Lincoln is able to pack more powerful thoughts into fewer words than any of his contemporaries.

He arrives at the convention on the wings of three magnificent speeches – at Peoria in 1854 attacking the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Springfield in 1858 warning of a “house divided,” and ten weeks earlier at Cooper Union in New York, demanding an end to the spread of slavery. These speeches, along with his ability to hold his own against Stephen Douglas in the 1858 debates, have made him into a credible contender in Chicago.

But still, he is still less well known than Seward and less plugged into the national party hierarchy than all four of his main competitors. He writes on March 24, 1860:

My name is new in the field; and I suppose I am not the first choice of a very great many. Our policy, then, is to give no offence to others – leave them in a mood to come to us, if they shall be compelled to give up their first love.

Instead of waiting for the delegates to come to him, he assembles his campaign team and goes on the offensive.

His supporters are drawn from different phases in his past. Many of them (Speed, Herndon, Logan, Browning, Oglesby, Koerner) share his ties to Kentucky. All have emigrated to Illinois, typically in the 1830’s, often to practice law and to participate in the state legislature. Their home bases vary, with some (Davis, Swett, Fell and Hatch) in Bloomington, others (Speed, Herndon, Logan, Dubois) in Springfield, Norman Judd in Chicago, Oglesby in Quincy, Gillespie in Galena, Koerner in Belleville, and Lamon in Danville. Most are contemporaries of Lincoln, within five years of his age, at fifty-one. A few are younger: his legal protégé, “Billy” Herndon (41), Leonard Swett and Richard Oglesby (both 35), and “Hill” Lamon (32). His most intimate, long-term friend is Joshua Speed, with whom he shared an apartment in 1837 upon his arrival in the state capital. Some are firmly in his camp from their first encounter; others, like Judd, Dubois and Browning, have occasion to waver in their support or affection.

The first campaign moves occur well before the convention. To broaden his name recognition and establish his core ideas, with the delegates and public alike, Lincoln publishes a popular 258 page book that recaps his debates with Douglas. He then adds an autobiography focusing on his personal history.

His chances improve markedly when Norman Judd convinces other members of the Republican National Committee to hold the nominating convention in Chicago rather than back east again in Philadelphia. This insures that large crowds of Lincoln supporters will attend the event, and that the local press will impress delegates with a barrage of editorials for their favorite son.

One week before the Wigwam event opens, he adds another victory at the Republican Party’s state convention in Decatur. David Davis, Jesse Fell, Norman Judd, and his other key strategists have set their sights on securing unanimous support for Lincoln among the Illinois delegation, especially since other contenders, like Cameron and Chase, are plagued by internal schisms. To help with this outcome, the youthful Decatur-based politician, Richard Oglesby, decides that Lincoln would benefit from a more dynamic and forceful image than simply “Honest Abe.” The result is a new moniker, Lincoln as the “Rail Splitter,” shirt-sleeves rolled up, wielding an ax, getting the necessary tasks accomplished swiftly and decisively. The candidate is said to burnish this vision of physical labor by quipping that, given ten hours to fell a tree, he would spend the first nine sharpening his ax. The Decatur delegates love Oglesby’s sell, and Lincoln walks away with the unanimity he sought.

At the same time, his confidence is bolstered by reassurances, especially from Jesse Fell, that beating Seward and Chase is within reach if he plays his cards right. The first step, according to his floor captain, Judge David Davis, will be to register 100 votes on the first ballot, and then try to scoop up support from those who defect as the voting wears on.

Sidebar: Early Friends And Supporters Of Lincoln

Here are the men who help carry Lincoln to the Republican nomination in 1860.

| Name | Age | Profile |

| David Davis | 45 | Ohio, Kenyon College, Yale Law, to Bloomington ’35 as lawyer, IL House ’45, ’48-62 Judge of 8th circuit in IL, a registered Independent, delegate and lead floor manager for AL in Chicago, often competitive with Judd, later US Supreme Ct ’62. |

| Norman Judd | 45 | New York, bar and move to Chicago in ’36, law practice, city attorney ’36-39, state Senate ’44-60, initially anti Nebraska Democrat, supports Trumbull over Lincoln for Senate ’54, breaks with Douglas over KN Act, then advisor to AL, helps with Douglas debates, Chair of Republican Party in IL, gets national committee to select Chicago site, nominates AL. |

| Orville Browning | 54 | Kentucky, Augusta College, passes bar and to Quincy IL in ’31, Blackhawk War, conservative Whig politics, serves terms in state legislature, another intimate friend despite some jealousy, also one of few who get on well with Mary L over time, US Senate ’61-63. |

| Joshua Speed | 45 | Kentucky plantation with slaves, to Springfield in ’35, runs general store, rents a room to AL in ‘37, considered his best friend, disagree on slavery but acts as constant sounding board, his brother James becomes Attorney General in ’64. |

| Leonard Swett | 35 | Maine, attends Colby College, into Mexican War, Bloomington IL as lawyer, rides circuit with AL, fails in bids for US House and Governor, but enter IL legislature in ’58, helps bring Seward into the eventual cabinet. |

| Richard Oglesby | 35 | Kentucky, orphaned, to Decatur IL in ’32, combat in Mexican War, Louisville Law School, gold rush, back to IL in ’51, helps found Republican Party there, IL legislature in ’60, creates “Rail Splitter” imagery to promote AL at the convention. |

| Stephen Logan | 60 | Kentucky, bar, to Springfield ’32 and meets AL, Circuit court judge,mentors AL, Logan & Lincoln law firm ’41- 43, dissolved when his son joins firm, prickly personality, four terms in state legislature but lost for higher slots, floor manager for AL try to defeat Shields for Senate ’55. |

| Jesse Fell | 52 | Pennsylvania Quaker, studies for bar in Ohio, to Bloomington IL in ’31, diverse career in law, newspapers, education, land development, AL friend since ’34, urges him to debate Douglas, especially close to Davis, tells AL he can defeat Seward and Chase, advisor on cabinet picks. |

| Jesse Dubois | 49 | IL native, wealthy family, Indiana College, four terms in state legislature ’34 on, moves to Springfield in house near AL, family friends in the ‘50’s, helps form Republican Party in IL at ’56 Bloomington Convention, State Auditor ’57-64, teams with Davis at Chicago to help win nomination, but bitter at the end when AL refuses his pleas for patronage jobs. |

| William Herndon | 41 | Kentucky, in Sangamon County ’21, works at father’s tavern in Springfield, one year at Illinois College, clerk at Joshua Speed’s store, apprentice lawyer at Logan & Lincoln firm ’40, bar in ’44 then Lincoln & Herndon ’44-65, “Billy” as surrogate son, Whig and Republican ties, not a confidante like Speed, but ever loyal. |

| Ward Hill Lamon | 32 | Virginia to Danville, IL, bar ’53, state prosecutor, pro South & anti-abolition, “fixer” role at convention and “extra tickets” to pack the hall, then bodyguard and US Marshal for DC per AL appointment. Called “Hill” Lamon. At Ford’s Theater in ’65. |

| Joseph Gillespie | 50 | NYC, to Galena IL in ’27, Blackhawk War, Transylvania Law School, state House as Whig in ’40 where befriends AL, state Senate ’46-58, law practice including IC railroad, momentarily a Know-Nothing but then helps found Republican Party in IL in 1856 at Bloomington Convention. |

| Ozias Hatch | 46 | New Hampshire, to Pike County IL in ’36, runs general store, on circuit court then state House ’51-53, at Bloomington to help found Republican Party, IL Secretary of State ’56-64 serving in Springfield, his office the “center of IL politics” at the time. |

| Gustav Koerner | 50 | Born in Frankfurt, Germany, JD from Heidelburg U, accused of treason as a revolutionary and flees to US in ’33, in Kentucky at Transylvania College, meets Mary Todd, to Belleville, IL in James Shield’s law firm, co-counsel with AL on some cases, into state legislature ’42, IL Supreme Court ’45-48, Lt Governor ’53-57, switches from Democrat to Republican over anti-slavery. Important link into foreign immigrant groups. |

May 17, 1860

Lincoln Wins The Nomination On The Third Ballot

The day before the convention opens, local editor, Joseph Medill, pitches in with an oversized headline – “The Winning Man: Abraham Lincoln” – in his Chicago Press and Tribune.

“Hill” Lamon and Davis also link up to rig the make-up of the 10,000 plus attendees on May 17, when the polling actually begins. Seating in the hall is “first come, first served” and requires a valid entry ticket. Lamon locates a printer who counterfeits “extra tickets” and then completes an early run by Illinois groups to pack the hall and dominate the cheering on behalf of Lincoln.

In addition to Davis and Judd, two other hand-picked delegates-at large, Orville Browning and Gustav Koerner, also play their roles on the floor. Browning is there to reassure conservative Whigs that Lincoln is more moderate and balanced that the “radical” Seward on the slavery issues. The German-born Koerner signals that Abe is not tied to the anti-immigrant Know Nothing faction within the party.

After the nominating speeches are completed – with Norman Judd offering Lincoln’s name – the first round of balloting begins. At this point, Seward’s manager, Thurlow Weed, remains confident of victory, and plans to recruit Lincoln for the Vice-Presidential slot, to help carry Illinois. He informs the delegation of this intent, and also volunteers a $100,000 payment to the Illinois Republican Party in exchange for their support of Seward.

But when the first ballot ends, Seward comes up well short of the 233 vote majority needed to win – while Lincoln squeaks past the 100 vote target set by Davis and Judd.

This opens up the potential for second ballot defections, and these prove fatal to Cameron, who drops from 50 votes down to two. The clear benefactor here is Lincoln, which sparks talk that the Lincoln men have bought off the Pennsylvanian with a promised Cabinet post. Honest Abe’s instructions to Davis in this regard have been loud and clear: “make no contracts that will bind me.” Despite this, the fact that Cameron ends up as Secretary of War, suggests that Davis may have done what he thought necessary at the moment.

On the second ballot, Seward actually adds eleven votes, but his lead over Lincoln shrinks to 184.5 – 181, and the momentum is clearly in favor of the challenger.

All of the stops come out as the roll is about to be called a third time. Leonard Swett works the Maine and New England delegates and Browning does the same with the Bates supporters in Missouri. When a sizable group of Ohioans swing to Lincoln, he is within 1.5 votes of victory on the third ballot, before a few “revisions” are called in that put him over the top. Seward’s men then gracefully call for unanimous consent to the sound of cheers throughout the hall.