Section #17 - The Republican Party emerges from an unlikely fusion of Free Soil and Know Nothing factions

Chapter 199: The Republican Hold Their Formal “Organizing Meeting” In Pittsburgh

February 22, 1856

The Founders Gather At Lafayette Hall

With the clock now ticking toward the 1856 elections, those dedicated to launching the Republican Party gather in Pittsburgh to put together their national organization and lay the groundwork for their first formal nominating convention to be held in the summer.

The same men who met at Francis Preston Blair Sr.’s house back in December oversee this two day event held at the Lafayette Hall, which bulges with some 800 attendees, half “delegates” and half spectators. They travel through wintry weather from every Free State in the nation, eight Slave States, and the territories of Kansas, Nebraska and Minnesota.

The New York contingent includes Preston King, from the prior Blair dinner, together with Edwin D. Morgan and Horace Greeley, both conduits to the crucial Thurlow Weed – Henry Seward camp. Ohio is represented by the abolitionists, Joshua Giddings and James Ashley, along with Jacob Brinkerhoff, co-author of the Wilmot Proviso.

Other notables include Wilmot himself from Pennsylvania, Owen Lovejoy (Illinois), Oliver Morton (Indiana) and Zachariah Chandler (Michigan).

Then, to the surprise of almost all, there is Francis Blair Sr., the very symbol of a disillusioned Democrat, who is quickly chosen to preside over the meeting and provide his thoughts on the need for a new party, which he does.

February 22-23, 1856

The Need For “Fusion” Dictates The Platform

The opening gavel sounds at 11am on February 22, chosen to honor Washington’s birthday, and in hopes of influencing events at the Know Nothing convention starting the same day in Philadelphia.

With guidance from Greeley, “caution” becomes the watchword of the speeches and platform work from start to finish – a necessity, he argues, if “fusion” is to take hold across those who arrive as Republicans or Know-Nothings or disgruntled Democrats.

The result is a fairly tame charter calling for repeal of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, immediate admission of Kansas as a Free State and a pledge to “resist, by every Constitutional means, the existence of slavery in any of the territories of the United States.” It takes no stand whatsoever on the role of “nativism.”

Not everyone is happy with this outcome.

Abolitionists like Gamaliel Bailey bemoan what they regard as a tempering on the issue of slavery. Instead of a strong positive call to expel it, the platform just passively reiterates opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Bill. Lewis Tappan sees similar danger for the cause, in his case because of the mere presence of Francis Blair Sr.:

Think of an anti-slavery Convention being presided over by a slave-holder.

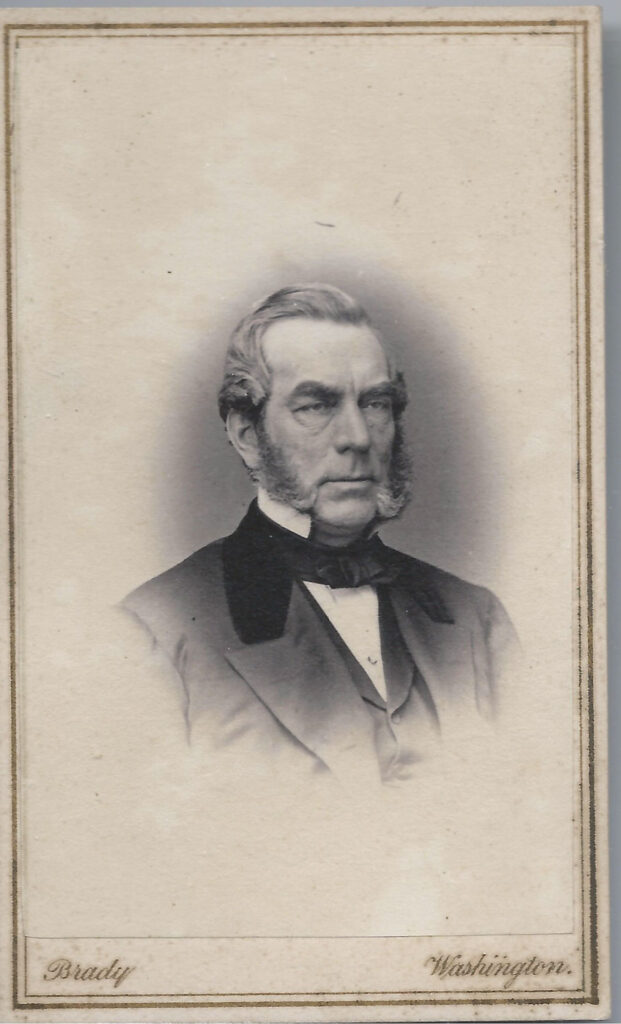

James Watson Webb — editor of The New York Courier & Inquirer and underhanded purveyor of a story that Tappan has married a black woman – feels that the Republicans have gone too far on slavery:

They commit me to Abolitionism. I am opposed to the extension of slavery, but am not in favor of abolishing it.

Regardless of these reservations, the “meeting” achieves its stated objectives.

Agreement is reached to hold the first official Republican Convention in Philadelphia on June 17-19, 1856. A national committee is identified, with soon to be Governor of New York, Edwin D. Morgan, as the first chairman. State networks are defined, along with plans to set them in motion.

The temptation to nominate presidential candidates is also avoided, despite pressure from supporters of Chase – and indeed none of the likely frontrunners attend in person.

Finally, efforts continue to find ways to divide the Know Nothing Convention, now in progress, along sectional lines over the issue of slavery. These are led by Chase’s Ohio representatives, and they prove successful.