Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

Chapter 117: The Republic Of Texas Is Annexed

December 1844 – February 1845

The Lame Duck Congress Again Debates The Texas Question

Polk’s aggressive stance on the annexation of Texas has much to do with his election victory – and he hopes that Congress will authorize its go-ahead by the time he is sworn in.

But complexities abound, not the least of which is to clarify the exact territorial boundaries being claimed by the Texans. At one extreme, “Imperial Texas” encompasses a huge swath of land from the Rio Grande River in the South to a northern tip in later day Wyoming, and extending west into later day New Mexico.

Meanwhile there is the much smaller land mass actually occupied by the Republic, sandwiched between two rivers, on the north and east, the Arkansas, on the south and west, the Rio Grande.

Both “claims” regarding the actual Texas boundaries are hotly disputed by the Government of Mexico. The debate over annexation is taken up by the 28th Congress in its lame duck session, which opens in December 1844, with Tyler still in the White House and Calhoun as Secretary of State.

While their Annexation Treaty was rejected six months earlier, both are convinced by the election results that public opinion now favors approval. To make passage easier this time, they abandon the prior attempt to approve a “treaty” with Mexico – needing a 2/3rd majority in the Senate – and instead go for a standard legislative bill, requiring only a simple majority.

In the House, however, efforts to shape a final bill are stalled over a host of issues, including: final “boundary definitions;” whether Texas will become a territory or a state; its “status” regarding slavery; and how its accumulated debts will be handled.

On January 13, 1845, a proposed solution is offered by Milton Brown, a Tennessee Whig, who studies law under Polk’s mentor, Felix Grundy, before becoming a leader among Southern Whigs, and a consistent thorn in the side of the Democrats. Brown argues in favor of immediately annexing the generally accepted, “narrow borders” of the Texas Republic, and holding over the broader land claims until Polk is in office.

His proposal involves four points:

- Act now to annex the existing Republic of Texas land, and immediately grant it status as a slave state.

- Assign all acreage to the state along with responsibility for any outstanding debts.

- Delay resolution over the “claimed land” until further U.S. treaty negotiations with Mexico can occur.

- Divide up any additional land acquired in the treaty negotiations into four more new states.

Brown’s plan to create additional slave states around Texas draws immediate fire, especially from the two leading Whig abolitionists in the House, JQ Adams and Joshua Giddings. The Ohioan’s remarks are particularly scathing. He says the annexation is not about patriotism; rather opening new slave markets to increase Southern wealth.

Texas is engaged in a war with Mexico and wants us to fight her battles…and a portion of this House say, we will do it, if, by that means, we can keep up slavery in Texas and thereby furnish a market for our slave-breeding states to sell their surplus population.

After further debate, however, Brown’s bill carries the House on January 25, 1845 by a 120-98 margin, decided along party, not regional, lines – with the vast majority of Democrats in favor and Whigs opposed.

The bill now moves to the Senate where it faces an even greater challenge, for two reasons: first, the Whigs still hold a majority during the lame duck session; and second, only six months ago, the powerful Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, opposed Tyler’s treaty and convinced seven other Democrats to also vote no.

Benton is sixty-two years old in 1845, a volatile figure that permanently shatters Andrew Jackson’s left arm in an 1813 duel, before reconciling with him. From then on, he becomes a leading force in Congress for passing the General’s legislation, especially around banking and hard money – where he earns the nickname, “Old Bullion.” Although a fierce “expansionist” – and father-in-law of the western explorer, John Fremont – his moral compass remains uncomfortable with any open-ended land grab from Mexico. Likewise his beliefs about slavery are evolving, especially around the wisdom of spreading it further into new states. This hesitancy will eventually cause Missouri voters to oust him in 1851.

But with Polk about to be in the White House, Benton changes his mind on Texas and decides to support the annexation. He calls for the existing Texas land (“narrow borders”) to be admitted immediately as a state, while any added land to become a territory, with “boundary and slavery issues” to be decided later by a five man commission set up by Polk. He feels that by delaying final calls on “slave vs. free” status for any other new states, more Northern Democrats will support the annexation.

Meanwhile Calhoun and his hard core faction in the Senate are lobbying for the broadest Texas borders, with all other land acquired being open to slavery right away.

February 28, 1845

The Texas Annexation Bill Is Finally Approved

At this point, Polk is frustrated by the lack of decisive action in the Senate. A possible solution comes from his soon-to-be Treasury Secretary, Senator Robert Walker of Mississippi, who proposes a combination of Brown’s plan to immediately annex existing Texas (“narrow borders”) along with Benton’s plan to delay closure on the broader “claimed lands” until later.

Benton signs on for this idea, believing, incorrectly, that Polk will be cautious in dealing with Mexico over “claimed land” conflicts, and on slavery-related issues. In turn, he whips all 25 Democrats into supporting the bill.

The Whigs, with 27 votes to cast, still threaten to defeat the annexation until two defectors from slave-holding states — the Maryland Senator, William Merrick, and the Louisiana man, Henry Johnson – swing the balance in favor of passage – 27 aye vs. 25 nay.

Senate Vote On Texas Annexation Bill: February 28, 1845

| Region | Dems Yes | Dems-No | Whigs Yes | Whigs No |

| Northeast | 8 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Northwest | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Border | 3 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Southeast | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Southwest | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 25 | 0 | 2 | 25 |

Aside from giving Polk the go-ahead to secure Texas, the annexation votes also shows that, on some issues, the Congress remains split along party lines – Democrats vs. Whigs – rather than along sectional/slavery lines – South vs. North.

Analysis Of Texas Annexation Vote

| Status | Yes | No |

| Democrats | 25 | 0 |

| Whigs | 2 | 25 |

| South States | 14 | 13 |

| North States | 17 | 17 |

Surprisingly in supporting the annexation, the North also goes along with handing the South a momentary two-state advantage in the balance of voting power in the Senate.

Post-Texas Admission

| Status | Count |

| South/Slave States | 17 |

| North/Free States | 15 |

On March 1, 1845, John Tyler signs the final Annexation bill into law.

The next step in the Texas scenario now belongs to a response from the Mexican government.

March 1, 1845

Sidebar: Final Texas Annexation Bill Calling For Popular Sovereignty Over Slavery

28th Congress Second Session. Joint Resolution for annexing Texas to the United States.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That Congress doth consent that the territory properly included within, and rightfully belonging to the Republic of Texas, may be erected into a new state, to be called the state of Texas, with a republican form of government, to be adopted by the people of said republic, by deputies in Convention assembled, with the consent of the existing government, in order that the same may be admitted as one of the states of this Union.

J W JONES

And be it further resolved, That the foregoing consent of Congress is given upon the following conditions, and with the following guarantees, to wit: First-said state to be formed, subject to the adjustment by this government of all questions of boundary that may arise with other governments; and the constitution thereof, with the proper evidence of its adoption by the people of said republic of Texas, shall be transmitted to the President of the United States, to be laid before Congress for its final action, on or before the first day of January, one thousand eight hundred and forty-six.

Second-said state, when admitted into the Union, after ceding to the United States all public edifices, fortifications, barracks, ports and harbors, navy and navy-yards, docks, magazines, arms, armaments, and all other property and means pertaining to the public defence belonging to said republic of Texas, shall retain all the public funds, debts, taxes, and dues of every kind which may belong to or be due and owing said republic; and shall also retain all the vacant and unappropriated lands lying within its limits, to be applied to the payment of the debts and liabilities of said republic of Texas; and the residue of said lands, after discharging said debts and liabilities, to be disposed of as said state may direct; but in no event are said debts and liabilities to become a charge upon the government of the United States. Third- New states, of convenient size, not exceeding four in number, in addition to said state of Texas, and having sufficient population, may hereafter, by the consent of said state, be formed out of the territory thereof, which shall be entitled to admission under the provisions of the federal constitution. And such states as may be formed out of that portion of said territory lying south of thirty-six degrees thirty minutes north latitude, commonly known as the Missouri compromise line, shall be admitted into the Union with or without slavery, as the people of each state asking admission may desire. And in such state or states as shall be formed out of said territory north of said Missouri compromise line, slavery, or involuntary servitude, (except for crime,) shall be prohibited.

And be it further resolved, That if the President of the United States shall in his judgment and discretion deem it most advisable, instead of proceeding to submit the foregoing resolution to the Republic of Texas, as an overture on the part of the United States for admission, to negotiate with that Republic; then, Be it resolved, that a state, to be formed out of the present Republic of Texas, with suitable extent and boundaries, and with two representatives in Congress, until the next apportionment of representation, shall be admitted into the Union, by virtue of this act, on an equal footing with the existing states, as soon as the terms and conditions of such admission, and the cession of the remaining Texan territory to the United States shall be agreed upon by the governments of Texas and the United States: And that the sum of one hundred thousand dollars be, and the same is hereby, appropriated to defray the expenses of missions and negotiations, to agree upon the terms of said admission and cession, either by treaty to be submitted to the Senate, or by articles to be submitted to the two Houses of Congress, as the President may direct.

Speaker of the House of Representatives.

WILLIE P. MANGUM

President, pro tempore, of the Senate.

Approv’d March 1. 1845

JOHN TYLER

Note: The Texas legislature previously approves the annexation and a constitution on Oct 13, 1845.

May 1845

A Small Minority Resist The Annexation Exists As Imperialistic

Despite the public popularity behind adding Texas, some Americans are troubled by what they see as Polk’s imperialistic actions.

The abolitionist Lloyd Garrison calls the Texas annexation “the greatest crime of our age.”

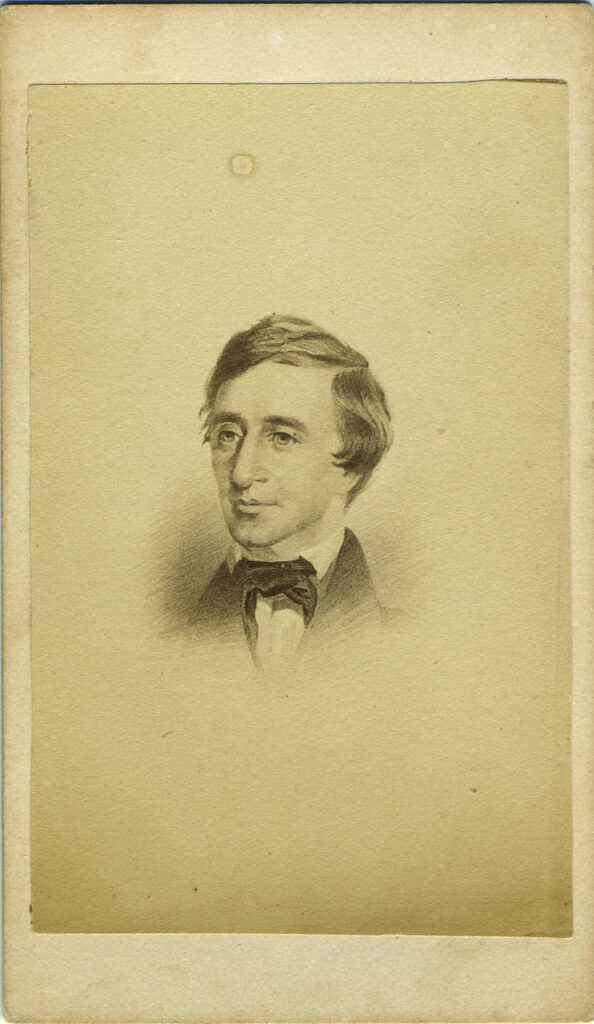

The New England transcendentalist, Henry David Thoreau, refuses to pay his $1 Massachusetts’s poll tax in protest, and spends a night in jail.

While released the next day, this experience leads to his 1849 treatise on “Civil Disobedience,” where he poses questions of conscience that resonate with time.

Can there not be a government in which majorities do not virtually decide right and wrong, but conscience? Must the citizen ever for a moment, or in the least degree, resign his conscience to the legislator?

How does it become a man to behave toward this American government to-day? I answer, that he cannot without disgrace be associated with it. I cannot for an instant recognize that political organization as my government which is the slave’s government also.

It is not a man’s duty, as a matter of course, to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous wrong?

Ohio congressman Joshua Giddings expresses his conscientious objections in no uncertain terms:

War, with all its horrors and its devastation of public morals, is infinitely preferable to a supine, inactive submission to the slaveholding power that is to control this nation if left in its present situation.

But these are the predictable abolitionist voices of protest – hardly enough to derail the momentum on Polk’s side.