Section #16 - Open warfare in “Bloody Kansas” follows fraudulent election wins for Pro-Slave State forces

Chapter 183: The Race Is On To Decide The “Slavery Question” In Kansas

Summer 1854

Anti-Slavery Emigres From Massachusetts Arrive In Kansas

As soon as it appears that Kansas will become a state, one Eli Thayer of Worchester, Massachusetts, formulates a plan to transport settlers there in order to open new towns, built on the virtues of free labor and capitalism.

Thayer’s roots are humble, but he makes his way through the Manual Labor School in Worchester and then Brown University, before opening the Oread Institute, a school for young women in 1848.

He is thirty-five years old in 1854 when he conjures his vision for developing Kansas, despite never visiting until some 23 years later. At first he sees the venture as a path to profiting on land speculation, and sets up a joint-stock corporation, with capital provided by businessmen like Alexander Bullock. But others who offer support – especially the wealthy anti-slavery philanthropist, Amos A. Lawrence and Unitarian minister, Edward Everett Hale – frown on the profit motive and convince Thayer to recast the venture as a “benevolent” work, under the name of the New England Emigrant Aid Society.

Thayer works tirelessly on the project, making some 700 appearances across the east, touting the society, signing up prospective travelers and raising money. He also publicizes it via advertisements in Greeley’s New York Tribune and William Cullen Bryant’s New York Evening Post.

His slogan becomes “Sawmills and Liberty,” based on the promise of providing settlers not only with temporary housing, but also with steam-powered equipment they will need to run their own mills and secure their economic independence. Several of Thayer’s supporters fear that he is too optimistic in his advocacy, but he is undeterred.

Prospects for the settlers are aided by federal land grants offered in July 1854, after treaties are negotiated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs with tribes who agree to sell their land and move south into Oklahoma. The largest transfer involves the Shawnees, who sell 6.1 million acres on May 10, 1854. Others who also reach agreements include the Otoes and Missouri (March 15), the Delaware (May 6), the Iowa (May 17), and the Kickapoo (May 18).

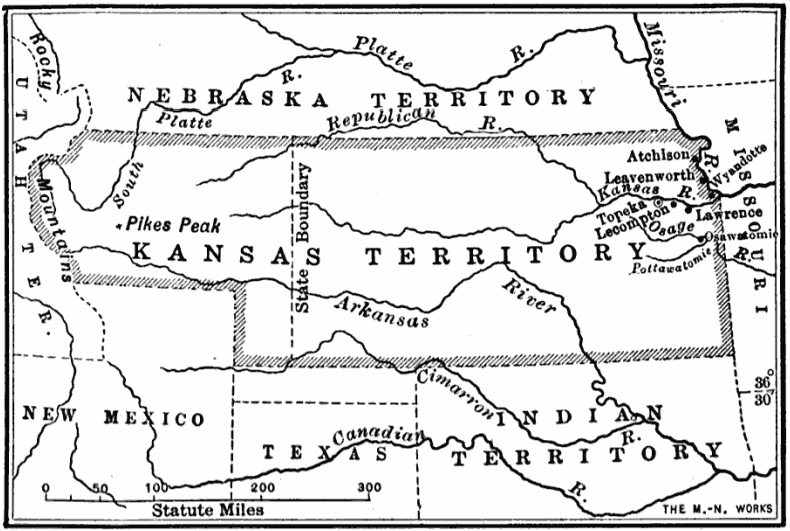

The first contingent of “New England Emigrants” – twenty-nine strong — arrives on August 1, 1854 in what will become Lawrence, Kansas — named after Thayer’s supporter, Amos Lawrence.

The subsequent flow of settlers is, however, disappointing – with estimates running between 900 and 2,000 in total. As of the 1860 Census only 4% of Kansans have emigrated from New England.

Despite this, the symbolic impact of the early arrivals is important. Lawrence will become the center for the Free State forces over time, and its newspaper, the Herald of Freedom, will help rally their efforts. The Society will also play a role in starting up the towns of Manhattan, Osawatomie, Topeka, and Burlington.

Word of the anti-slavery easterner’s presence will soon provoke a response from pro-slavery rivals in Missouri.

As for Eli Thayer, the recognition he gains from his efforts in Kansas are rewarded in his election to the U.S. House in 1857-1861, running both times as a Republican.

Summer 1854

Southern Associations Form Up To Promote Slavery

Once Northern opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Bill gains traction, the South responds with various pro-slavery “associations” of its own.

One is the “Order of the Knights of the Golden Circle” comprising those who hope to open new slave territory in Mexico, Central America and Cuba, in addition to the American west. The Order is founded on July 4, 1854 in Lexington, Kentucky by “General” George W. Bickley and four of his friends. Bickley himself is a genuine character, born in Indiana before moving to Virginia, where he practices medicine despite dubious credentials, and then relocating to Cincinnati, promoting various filibustering campaigns which fail to materialize. He soon vanishes, but his society and its local “castles” or meeting lodges live on throughout the Civil War.

These associations are typically secret and mirror the kinds of practices and rituals familiar to the Freemasons. Their names vary by locale, from the “Golden Circle” to the “Friends of the South,” the “Social Band” and the “Dark Lantern Society.”

The Missouri branch is known as the “Platte County Self-Defense Association.”

It is founded on July 20, 1854 to insure that neighboring Kansas be admitted to the Union as a Slave State.

Its Secretary is Benjamin F. Stringfellow, raised among wealth in Virginia before moving west to Missouri in 1839, where he practices law and, along with his doctor brother, John, publishes the Squatter Sovereign newspaper. He is elected to the Missouri legislature as an “anti-Benton” man, serves as Attorney General from 1845 to 1849, and becomes a General in the Missouri State Militia.

In 1854 he fears that if Kansas becomes a Free State, run-away slaves will flock across the Missouri River to safety. His answer lies in setting up “Blue Lodges” across both states to combat the abolitionists.

Summer 1854

Senator David Atchison Rallies Southern Forces Against Prospective Free Soil Settlers

Stringfellow’s partner in establishing the Blue Lodges is none other than David Rice Atchison of Missouri, sitting President Pro Tempore of the U.S. Senate!

Atchison grows up on a plantation near Lexington, Kentucky, before graduating from Transylvania University and moving to Liberty, Missouri in 1830. He opens a legal practice there with his friend and law partner, Alexander Doniphan, and both men join a state militia unit known as the Liberty Blues. Atchison is elected to the Missouri House in 1834, where he helps secure what becomes Platte County, in the northwest corner of the state, through purchase treaties with local Indian tribes.

When the Mormon War breaks out in 1838, Atchison is named Major-General in the state militia, which restores peace and protects the prophet, Joseph Smith, and his followers from further harm.

Both his law and political careers flourish. In 1841 he is a circuit court judge and a member of Masonic Lodge #56. Two years later, Governor Thomas Reynolds appoints him to the U.S. Senate after Dr. Lewis Lynn dies in office. While only thirty-six at the time, his new colleagues appreciate both his competence and outgoing manner, and, in 1845, elect him President Pro Tempore, a post which gives him the gavel should the Vice-President not be present in the chamber.

In 1854, Atchison is back in that role, made even more influential after Pierce’s Vice-President, William King, dies in April 1853 and is not replaced. This puts Atchison next in line to become President should Pierce die in office.

But Atchison’s agenda in the Senate is eclipsed in the summer of 1854 by absolute determination to see that Kansas enters the Union as a Slave State. As he writes at the time:

The prosperity or the ruin of the whole South rests on the Kansas struggle.

The notion of Northern interlopers trying to ban slavery directly west of Missouri is enough to resurrect the violent side of his character, not seen since his earlier days in the militia.

He vows in July 1854 that The Platte County Self-Defense Association will attack all Free Soilers in Kansas.

He christens his supporters the “border ruffians” and promises to “kill every god-damned abolitionist coming into the district.”