Section #18 - After harsh political debates the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision fails to resolve slavery

Chapter 204: The Political Parties Convene To Select Candidates For The 1856 Races

February 22 – September 18, 1856

Six Separate Political Conventions Are Held In 1856

Amidst the chaos in Kansas, a total of six political conventions are held to finalize platforms and select nominees for the upcoming 1856 presidential election.

Of the six, only the Democratic Party enjoys a sense of historical continuity. The other five involve parties that are either crumbling or in disarray or just beginning to form up.

National Political Conventions In 1856

| Dates | Party | City |

| February 22-23 | Republican “Pre-Meeting” | Pittsburg |

| February 22-25 | American/Know Nothings | Philadelphia |

| June 2-6 | Democrat | Cincinnati |

| June 12-15 | “North American Seceders” | New York |

| June 17-19 | Republican | Philadelphia |

| September 17- 18 | Whig | Baltimore |

Three of the conventions occur between June 2 and June 19.

The June 2-6 meeting for the Democrats is their seventh quadrennial event in a row going back to 1832, when Andrew Jackson is nominated for a second term. Their only break with tradition is a move west to Cincinnati, after six prior events held in Baltimore.

Next come the so-called “North American Seceders” who gather in New York on June 12-15. The delegates here are the same ones who caused the fatal schism in the Know-Nothing Party by bolting its February convention.

On June 17-19, the fledgling Republican Party holds its first formal convention in Philadelphia, intent on finalizing its platform, opening its arms to as many new converts as possible, and settling on a credible standard bearer.

Finally, in September, a straggling band of Whigs who have yet to join either the Republicans or the Know Nothings, meet in Baltimore for what will be their last time.

What all six of these events share is an uncomfortable sense of flux and uncertainty that is also gripping the entire republic. Can the political parties hold together in the face of the Kansas Nebraska Act; can the nation itself hold together? In their own ways, each of the political sessions is marked by divisiveness.

June 2-6, 1856

A Shaken Democratic Party Considers Three Presidential Contenders

The mood of Democratic delegates on the opening day of their Cincinnati convention is a far cry from what was anticipated, given the collapse in 1852 of their longtime Whig rivals. Instead of unity and optimism, events during the Pierce presidency have bred disappointments and the specter of sectional division.

The turning point for the Democrats has been the negative response across the Northern states to the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which re-opens the possibility of extending slavery into all territories west of the Mississippi River.

While Stephen Douglas and a once reluctant Pierce regard the Act as a high-minded example of democracy in action – i.e. “let the people choose” – the majority of Northerners regard it as a betrayal of the 1820 Missouri Compromise and an outright surrender to the “Slave Power” in the South. This gives rise not only to the formation of a new opponent in the Republican Party, but also the defection of many previously stalwart Democrats, including men like Hannibal Hamlin, Ben Butler, and Montgomery Blair.

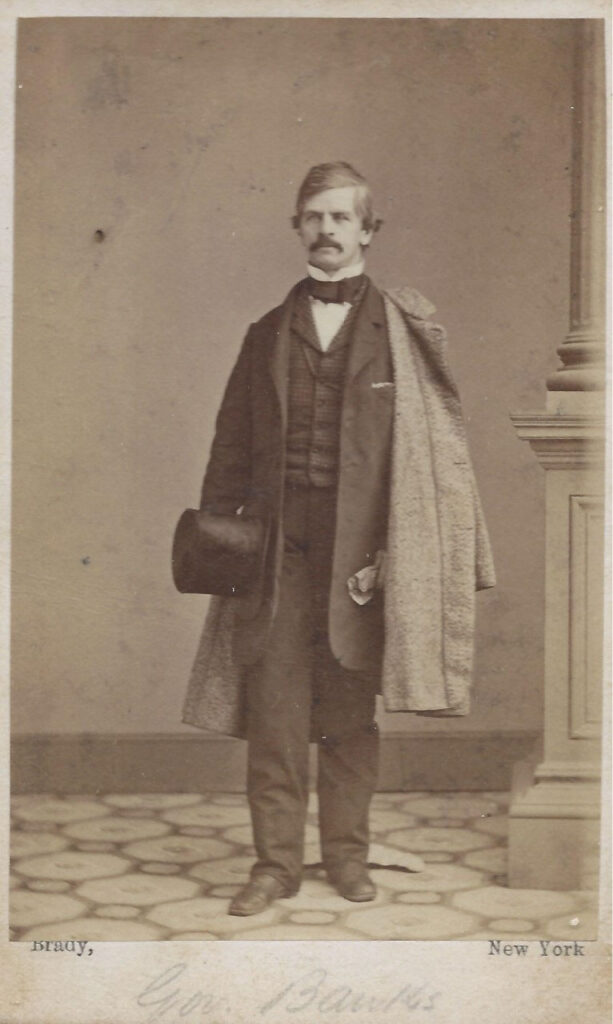

The political effects of the 1854 Act are already evident in the mid-term elections where Democrats surrender 75 seats in the House, and a Know-Nothing candidate, Nathaniel Banks, is chosen as its Speaker.

Even within the Southern wing of the party, there are reservations about Pierce’s record in office. Once again, all attempts to open new slave territories beyond America’s borders have failed. A filibustering initiative by William Walker in Lower California is rebuffed, and one more attempt to take over Cuba has ended in the humiliating rejection of the Ostend Manifesto.

On top of that, there is the alarming threat to the Union being played out in Kansas, with its fraudulent elections, two competing legislatures, inept governors and accelerating levels of violence – the Wakarusa incident, assaults on U.S. Marshals, the sack of Lawrence, John Brown’s reprisal murders at Potawatomie, and the Battle at Black Jack.

Despite this baggage, the fifty-two year old Franklin Pierce still hopes to be re-nominated, ignoring his prior pledge to depart after a single term. His reputation across the South remains largely positive, with one newspaper calling him “a lion in the pathway of fanatics” for his defense of slaveholder rights in Kansas. He enjoys pockets of strength in New England, including his home state of New Hampshire, along with Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Vermont. When he asks his cabinet in November 1855 if he should run again, all say yes. And so he runs again.

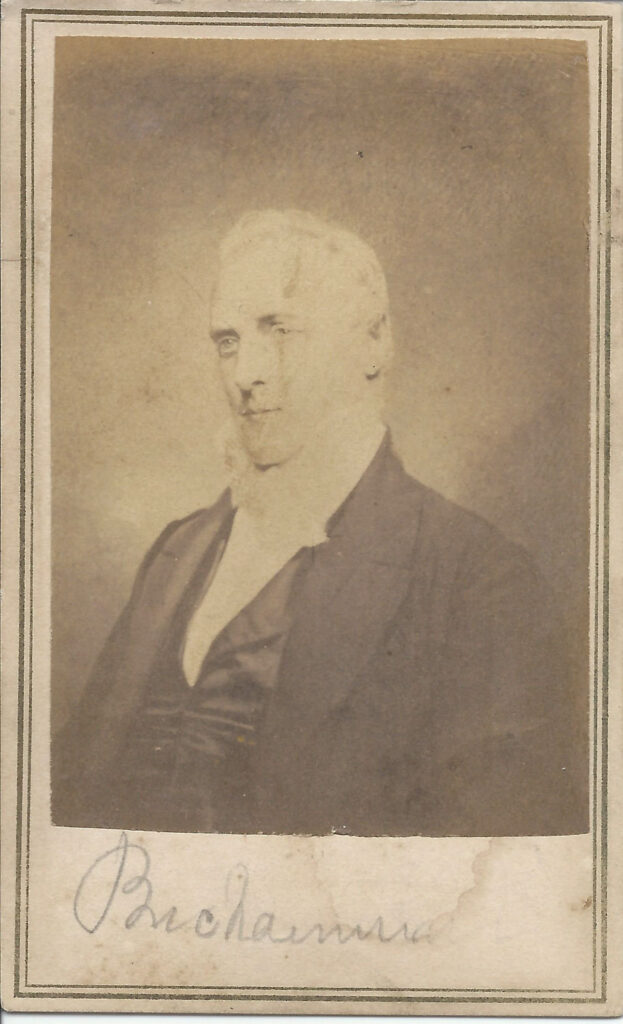

His two leading opponents have long shared an ambition to become president. One is the acknowledged leader of the Democratic caucus in Congress, Stephen Douglas, still relatively young at forty-three. The other is Pierce’s Minister to Great Britain, James Buchanan, age sixty five, a public servant since 1821 and long “waiting his turn.” Both men have earned nomination votes at prior conventions, in Buchanan’s case, as far back as 1844.

Prior Votes For The Democratic Nomination

| 1844 | 1848 | 1852 | |

| Stephen Douglas | 0 | 0 | 102 |

| James Buchanan | 26 | 55 | 92 |

Douglas, however, comes to the gathering with similar baggage as Pierce, having been lead author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and it’s most visible and contentious defender in the face of criticism. Meanwhile, Buchanan has been in England for two years, sheltered from most of the controversy.

The convention itself opens on a note of conflict, when two competing delegations appear from New York, one if favor of Pierce, the other led by the ever obstinate Daniel Dickenson, backing Buchanan. Both groups are seated with each member awarded a half-vote, thus ending Pierce’s chances of winning the Empire state. Other strong figures also oppose his re-nomination, particularly Governor Henry Wise of Virginia and Senator Jesse Bright of Indiana.

No surprises materialize on the platform, which predictably reaffirms both the 1850 Compromise and the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act – the “only safe and sound solutions” on the issue of slavery.

June 6, 1856

James Buchanan Emerges As The Democratic Nominee

June 5 brings the first day of balloting for president. According to convention rules renewed in 1844, a nominee must receive two-thirds of all votes cast to secure a victory. In effect this rule insures that a Southern coalition, unified around shared aims on slavery, will be able to veto any candidate who opposes their wishes.

The initial vote shows a close race between Buchanan and Pierce, with neither man even able to muster a simple majority. At this point, Pierce leads “Buck” in the Slave States by 74-34, with Mississippi giving the remaining 9 Southern votes to Douglas, whose well concealed plantations are there.

Over half of Buchanan’s votes reside in just three states: Ohio, Indiana, and Pennsylvania. As expected, New York divides down the middle, with an 18-17 edge to Pierce.

Both men exhibit staying power until the sixth ballot, when Buchanan creeps up to the 155 level after Tennessee momentarily shifts his way from Pierce. The President’s slide continues on the seventh vote, as those opposed to Buchanan begin to test Douglas’s upside potential.

By the 16th round it’s clear that neither Douglas nor Pierce can overtake Buchanan.

After apparently receiving an assurance from “Buck” to endorse him in the 1860 contest, Douglas withdraws his name and the voting ends.

Votes Cast For The Democratic Presidential Nomination In 1856

| Candidates | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 6th | 7th | 10th | 14th | 15th | 16th | 17th |

| James Buchanan | 135.5 | 139.0 | 139.5 | 155.0 | 143.5 | 147.5 | 152.5 | 168.5 | 168.0 | 296.0 |

| Franklin Pierce | 122.5 | 119.5 | 119.0 | 107.5 | 89.0 | 80.5 | 75.0 | 3.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Stephen Douglas | 33.0 | 31.5 | 32.0 | 28.0 | 58.0 | 62.5 | 63.0 | 118.5 | 122.0 | 0 |

| Lewis Cass | 5.0 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 0 |

| Total | 296.0 | 296.0 | 296.0 | 296.0 | 296.0 | 296.0 | 296.0 | 295.0 | 296.0 | 296.0 |

| Needed To Win | 197 | 197 | 197 | 197 | 197 | 197 | 197 | 197 | 197 | 197 |

The Vice-Presidential slot goes on the second ballot to 34 year old John C. Breckinridge, a Princeton graduate, veteran of the Mexican War, practicing attorney in his home state of Kentucky and a previous backer of Pierce for the presidency.

Pierce is disappointed by his rejection, but vows to support the ticket and predicts a Democrat win in the vote ahead. The New York Times pulls no punches in summing up his political journey as follows:

He was taken up in the first place because he was unknown, and now he is spurned because he is known.

Sidebar: Why The Democrats Nominate Northern “Doughfaces”

James Buchanan follows Lewis Cass of Michigan and Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire as the third Democratic nominee in a row from the North who embraces political policies that tilt toward the South, thus the moniker, “Doughfaces.”

But why should the Democrats nominate these men for President in 1856 when only four of the nation’s first fourteen elections have gone to Northerners (the two Adams, Van Buren and Harrison) – and two of the last three winners have come from the South (Polk and Taylor)?

And doubly so when several possible Southern Democrats look at least as credible as James Polk when he was nominated 1844 — Democrats like Jefferson Davis, Lin Boyd, Wise, Houston, Johnson and Guthrie. (Other qualified Southerners also exist – Robert Toombs, John J. Crittenden, Alexander Stephens, John Bell and Howell Cobb — but they are either Whigs or Democratic drop-outs.)

Seemingly Qualified Southern Candidates For The Democratic Nomination: 1856

| Candidates | State | Age | Credentials |

| Jefferson Davis | Miss | 48 | Military, US House ’45-46, Mexican War hero, US Senate ’47-51, Secretary of War ’53 to present |

| Lin Boyd | Ky | 56 | Farmer, US House ’35-55, Speaker of House ’51- 55, key player in Compromise of 1850 |

| Henry Wise | Va | 50 | Lawyer, US House ’33-44 as Whig, Minister to Brazil ’44-47, Democrat by ’47, Virginia Gov ‘56 |

| Sam Houston | Tex | 63 | War of 1812, lawyer, US House ’23-27, Tenn Gov, Rep of Texas President, US Senator ’46 to present |

| Herschel Johnson | Ga | 54 | Lawyer, US Senate ’48-49, Governor of Georgia ’53 to present |

| James Guthrie | Ky | 64 | Lawyer, state legislature, President U-Louisville, Secretary of Treasury ’53 to present |

Three factors explain the Democrat’s “Northern Doughface” strategy.

The first is that nearly 60% of all the electoral votes continue to be concentrated in the Northern Free States.

Distribution Of Total Electoral Votes For The Presidency

| 1832 | 1836 | 1840 | 1844 | 1848 | 1852 | 1856 | |

| Northern Free States | 58% | 57% | 57% | 58% | 58% | 59% | 59% |

| Southern Slave States | 42 | 43 | 43 | 42 | 42 | 41 | 41 |

Second is history, which shows that to win the election, a candidate must be able to secure over 55% of all the Northern electoral votes. Although both Polk and Taylor meet that threshold, Northerners like Harrison and Pierce enjoy much higher margins.

Percent Of Electoral Votes By Region Enjoyed By Presidential Winners

| 1832 | 1836 | 1840 | 1844 | 1848 | 1852 | |

| Winner | Jackson | Van Buren | Harrison | Polk | Taylor | Pierce |

| Home State | Tenn | NY | Ohio | Tenn | La | NH |

| Party | Dem. | Dem. | Whig | Dem. | Whig | Dem. |

| All Electoral Votes | 286 | 294 | 294 | 275 | 290 | 296 |

| Northern Free States | 165 | 168 | 168 | 161 | 169 | 176 |

| Southern Slave States | 121 | 126 | 126 | 114 | 121 | 120 |

| Winner’s Total E Votes | 219 | 170 | 234 | 170 | 152 | 254 |

| Northern Free States | 132 | 99 | 156 | 103 | 97 | 158 |

| Southern Slave States | 87 | 71 | 78 | 67 | 55 | 96 |

| % North E Votes Won | 80% | 59% | 93% | 62% | 57% | 90% |

| % South E Votes Won | 72 | 56 | 62 | 59 | 45 | 80 |

Finally, and of the greatest importance to Democratic strategists in 1856, is the sense that Northern voters are turning against them on issues surrounding slavery – first the negative reactions to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, then to the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Bill. The 75 seat loss in the House, overwhelmingly centered in the North, demonstrates this backlash.

Hence the Democrat’s choice of a third consecutive Doughface in Buchanan.

Within the Cincinnati convention, Southern delegates, who retain veto power over the nominee by means of the 2/3rds rule, see him as sufficiently amenable on slavery-related issues. Beyond the convention, the hope is that his Pennsylvania background and his absence in Britain during the Kansas-Nebraska furor will prove acceptable to Northern voters in the Fall. (The actual outcome will show that Buchanan goes on to win only because of his near total dominance in the South and the fact that the Northern vote gets split between his two opponents, Fremont and Fillmore.

June 12-15, 1856

Republican Party Maneuvers Begin Before They Open Their Convention

As the Republicans prepare for their convention they attempt to influence the outcome of the convention held by the “Seceder delegates” who left the Know Nothing Party back in February.

They are Northerners, from New England across the Midwest, and are united in demanding a candidate who opposes not only Catholic immigrants but also the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the possibility of slavery migrating to the west. This latter fact threatens to siphon off votes from whomever the Republicans choose.

To avoid this outcome, two men — Thomas Spooner of Ohio and Ohio Governor, Salmon P. Chase – attempt to align the “Seceders” with the new Republican Party, as part of the “fusion strategy.”

But pulling this fusion off will be tricky since the Know Nothings are much more opposed to immigration and Catholics than are most Republicans.

To attract them without offending the other Republican factions, Chase explores a modified platform stance on immigration. Instead of the “Seceder’s” wish for a flat out ban on non-native-born citizens holding political office, perhaps all immigrants should be required to renounce any foreign allegiances. Instead of requiring twenty-one years of residence before an immigrant can become a citizen, perhaps the prior five year delay might still suffice.

While Chase is formulating his strategies, so too are a wide range of other Republican operatives, most notably the New York kingmakers, Edward D. Morgan, first Party Chairman, Thurlow Weed, Isaac Sherman and Horace Greeley.

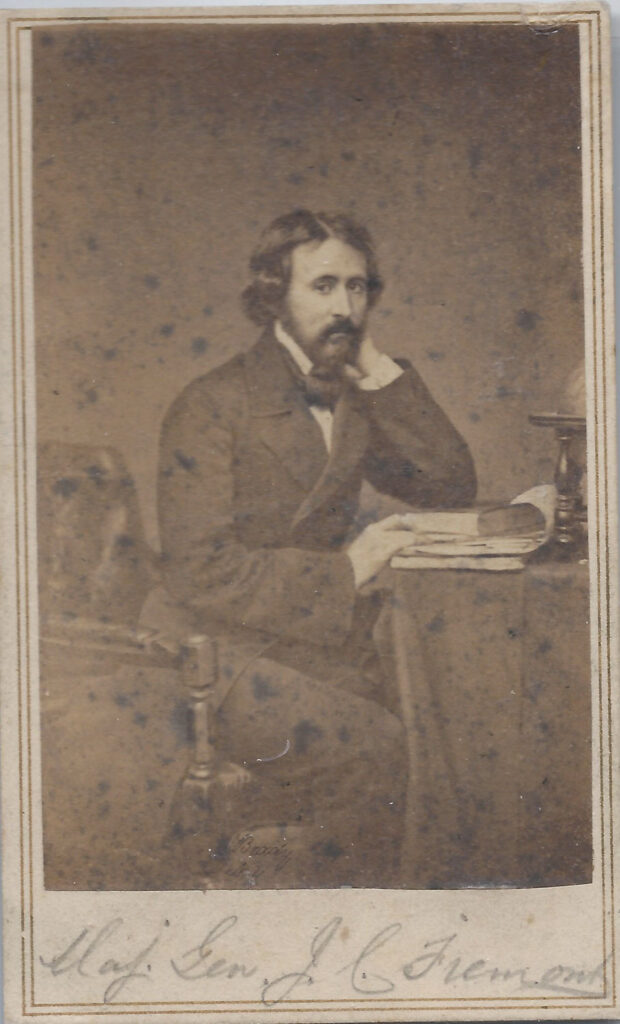

Their preferred candidate is John C. Fremont, the western “Pathfinder,” who they see as “less defined” or polarizing on slavery and immigration, and therefore most credible as a “fusion” alternative.

Other Key Republican Party Strategists Hoping To Achieve Fusion With The “Seceders”

| State | Credentials | |

| Edwin D. Morgan | New York | First Chairman of the Republican National Committee, businessman, later NY Governor & Senator |

| Thurlow Weed | New York | Editor Albany Evening Journal, head of Whig machine in NY, Henry Seward’s sponsor, anti slavery voice |

| Horace Greeley | New York | Editor, New York Tribune (highest US circulation), abolitionist, socialist, reform activist, influencer |

| Francis P Blair, Sr. | Washington DC | Jackson loyalist turned Republican, presides at early Pittsburg convention to form party, Fremont backer |

| Preston King | New York | Democrat turned Barnburner, Free Soiler and then Republican, strategist, later US Senator from NY |

| Isaac Sherman | New York | Lumber business, investor in Southern railroads, back-stage politician, Free Soiler, then Fremont supporter |

| Henry Wilson | Massachusetts | Humble shoemaker turned politician, US Senator as momentary Know-Nothing, abolitionist, party founder |

| Schuyler Colfax | Indiana | South Bend Free Press, Greeley friend, US House as Know Nothing, but anti-slavery & KN Act, founder |

These men fear the “Seceders” will nominate Fremont, thus “branding” him as a Know Nothing among the Republican delegates at their convention.

To avoid this outcome, they go to work on several prominent “Seceders,” including the brash financier George Law, still angry over his loss of the party nomination to Millard Fillmore in February, and influential Mayor Robert T. Conrad of Philadelphia.

They also appeal to Nathaniel Banks himself to come on board as a Republican rather than a Know Nothing, and back Fremont.

It is Isaac Sherman who approaches Banks prior to the convention with a proposed “finesse” that would allow the “Seceders” to eventually back Fremont if they choose to, but without actually nominating him at their convention. In a letter, Sherman suggests an option whereby the popular Banks would win the nomination, but then decline it later on in favor of Fremont. With the implication that, in exchange, the Republican Vice-Presidential slot could go to a Know Nothing.

Would it not be well to have the KN’s nominate you on the 12th of June for President and some Whig like Gov. Johnson (sic) of Penn for Vice-President Johnston as VP. and then you decline the moment that the Republican Convention in Philadelphia has nominated Fremont. Could we not have an understanding of this kind which would virtually give the KN’s the nomination of the Vice president?

That manipulative scenario is what transpires in New York. Banks leads the balloting from start to finish, first surpassing Fremont, and then, later on, Judge John McLean, a conservative Whig from Ohio, currently serving on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Votes Cast At The Know Nothing Seceders’ Convention In 1856

| Candidates | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th |

| Nathaniel Banks | 43 | 48 | 46 | 47 | 46 | 45 | 51 | 50 | 50 | 53 |

| John C. Fremont | 34 | 36 | 37 | 37 | 31 | 29 | 29 | 27 | 28 | 18 |

| John McLean | 19 | 10 | 2 | 29 | 33 | 40 | 41 | 40 | 34 | 24 |

| Robert Stockton | 14 | 20 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| William Johnston | 6 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Others | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 121 | 115 | 118 | 113 | 111 | 116 | 121 | 117 | 112 | 95 |

Having won the votes, however, Banks, according to the plan, fails to accept the nomination on the spot.

Instead, he stalls until after the Republican Convention, and then throws his support behind Fremont, while encouraging the Know Nothing Seceders to follow suit.

Some will go along. Others will be offended by the backroom maneuvering and any loss of focus on the “America for Americans” theme.

June 17, 1856

The Republicans Open Their First Formal Nominating Convention

It is now the Republican’s turn to coalesce as a national party, and they do so at the Musical Fund Hall in Philadelphia June 17-19. Attendance tops two thousand with 567 official delegates and the rest there to observe and support their favorite candidates.

Since their February meeting in Pittsburgh, Republican headquarter operations have sprung up in states across the nation, headed by politicians of all stripes – ex-Whigs, transitional Know Nothings, and Free Soil Democrats.

Some Statewide Leaders In The New Republican Party

| States | Electoral | Early Converts |

| New York | 35 votes | George Morgan, Thurlow Weed, Henry Seward, Preston King, Greeley, etc. |

| Pennsylvania | 27 | Know Nothings Thad Stevens and Simon Cameron, Free Soiler David Wilmot |

| Ohio | 23 | Free Soilers Salmon Chase, Joshua Giddings, John McLean |

| Massachusetts | 13 | Know Nothings Nathaniel Banks and Henry Wilson |

| Indiana | 13 | KN Schuyler Colfax, anti-slavery Democrat Oliver Morton, Whig Henry Lane |

| Illinois | 11 | Anti-Douglas men: Lyman Trumbull, Orville Browning, Abraham Lincoln |

| Maine | 8 | Anti-slavery Democrat Hannibal Hamlin, Whig Israel Washburn |

| New Jersey | 7 | Ex-Whig William Dayton |

| Connecticut | 6 | Anti-slavery Democrat Gideon Welles |

| Michigan | 6 | Anti-slavery Whig Zachariah Chandler |

| New Hampshire | 5 | Oppositionist John Hale |

| Vermont | 5 | Ex-Whig Solomon Foot |

| California | 4 | John C. Fremont |

| Iowa | 4 | James Grimes |

Among those who continue to pull the strings at the convention in search of “fusion” are six men in particular:

- Edwin D. Morgan, chair of the Republican national committee, who presides over the event;

- Thurlow Weed, the long-time leader of the New York Whigs, and political handler for Henry Seward;

- Nathaniel Banks, Speaker of the House and darling of the Know Nothing Party;

- Francis Blair Sr., symbol of the anti-slavery Free Soilers who have abandoned the Democrats; and

- Two prominent journalists, Horace Greeley (The New York Tribune) and John Bigelow (New York Evening Post.)

The first order of business lies in crafting a platform, and the result is one that is widely applauded by all opposed to the spread of slavery – either on moral grounds, racial antipathy toward blacks, or in defense of the “dignity of white labor” against the denigrating effects of more southern plantations.

The final document opens with praise for the Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution and the sacred Union, and trumpets Salmon Chase’s belief that the founding fathers intended for slavery to wither away rather than spread and prosper. It says that Congress retains “sovereign power” over the new territories and that it has:

Both the right and the imperative duty…to prohibit in the territories those twin relics of barbarism – polygamy and slavery.

Predictably it goes on to call for repeal of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, attacks the Pierce administration for a litany of failures that endanger the Union, and demands the immediate admission of Kansas as a Free State.

Beyond that, the platform goes out of its way to avoid divisive issues. No references are made to abolition, even in the District of Columbia. Gone too are traditional Whig vs. Democrat clashes over tariffs, the banking system and federal spending on infrastructure.

Also almost entirely glossed over are the Know Nothing’s issues around immigration and the “Catholic threat” — with one exception – an oblique reference to protecting the “liberty of conscience,” thought to support the presence of the King James Bible in public school classrooms. While nativist concerns do draw some platform discussions, the feeling seems to be that if Know Nothing leaders like Banks, Wilson and Colfax support the Republican cause, their fellow lodge members will follow suit.

June 18, 1856

The Platform Crystallizes “The South” As The Threat To The Nation

As the convention progresses it becomes clear that the Republicans no longer regard their opposition as the Democratic Party, but rather The South – and not simply its 330,000 or so slaveholders, but the section as a whole.

Thus the term “Slave Power,” previously the attack phrase of the abolitionists, is adopted by the convention as the nom de guerre of the true enemy – along with its Doughface lackeys like Pierce, Buchanan and Douglas.

This coalition, the Republicans argue, threatens the very foundational values which have made America great.

Instead of a culture where every white man enjoys a roughly equal shot at economic success and upward mobility, the South operates more like an aristocracy of planter princes living in luxury, surrounded by hardscrabble serfs struggling for economic survival.

Instead of rejecting human bondage as a violation of natural law, the South clings to its “peculiar institution” and the moral debasements which accompany it.

Instead of dignifying the value of free labor, Southern elites make a mockery of it in their reliance on slave labor.

So too with the democratic principle of “majority rules,” which the South tries to frustrate through the power of its monolithic voting block or through calls for “nullification.”

Then comes a resort to violence, as demonstrated recently in the Border Ruffians marauding in Kansas and the brutal caning of Charles Sumner on the floor of the Senate.

Finally, if it fails to get its way by other means, the South threatens to break its sacred contract with the other states and secede from the Union.

Nothing animates the convention delegates more than what they see as the Republican Party commitment to protect America’s core values against the threats posed by the Slave Power — with their weapon of choice being a flat out denial of the South’s demand to take slavery into the west.

In one fell swoop the Republicans say this denial will signal the triumph of the common man over the Southern aristos, of free labor over slave labor, of majority rule over nullification, of good over evil. The cause is just; let right be done.

Once the moral case is established, the political question becomes how many other Northerners, especially Democrats, will step up in November 1856 to join the Republicans in resisting the Slave Power?

June 19, 1856

The Republicans Choose John C. Fremont As Their Nominee

With the platform locked down and high levels of enthusiasm in the hall, the delegates turn their attention to selecting the party’s first nominee for president, a moment that will actually prove anti-climactic.

A total of five men have been under consideration by Republican leaders since the opening dinner at Francis Blair’s house back in December 1855.

Five Potential Candidates For The Republican Nomination In 1855

| Name | Age | State | Prior Party | Current Status |

| Nathaniel Banks | 40 | Mass | Know Nothing | Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives |

| Salmon Chase | 48 | Ohio | Free Soil | Governor of Ohio |

| John C. Fremont | 43 | Cal | Undeclared | Ex-Senator from California now living in NYC |

| John McLean | 71 | Ohio | Whig | Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court |

| Henry Seward | 55 | NY | Whig | U.S. Senator from New York |

Banks is considered too much of a Know Nothing and too little of a slavery opponent to qualify for the nomination. Besides, he has already declared in favor of Fremont.

Chase is associated with the hard core abolitionists, lacks personal magnetism, and arrives without the full support of his home state of Ohio, where many still back his Whig rival, John McLean.

Judge McLean retains some support at the convention among the conservative Whigs, but he is seventy-one and viewed by many as an “old fogie” rather than the fresh face needed by a brand new political party.

Then there is Henry Seward, regarded by many as the ideal choice, and reportedly receiving the loudest cheers of support within the hall. But he struggles mightily to decide whether or not to run after his long-term advisor, Thurlow Weed, assures him that the Republicans simply cannot win in 1856.

Weed’s math is compelling and will turn out to be correct. It begins with the assumption that the Anti-Slave Power party platform will cost the Republican all 120 electoral votes residing in the South – thus leaving only 176 in play, and a need to win 149 of them for victory.

Despite the troubling prospect of a third party of “hold-out Whigs,” Weed believes that the new party can carry New England, New York, Ohio and the Upper Midwest for a total of 114 electoral votes. But to achieve the 149 total needed to win, the Republicans must still get 35 of the 62 votes in the remaining “toss-up” states.

The biggest single barrier to this result is Pennsylvania, Buchanan’s home state and one where the Republican party infrastructure has been weak all along. Organizational problems also exist in New Jersey and California for sure, and to some extent in Illinois and Indiana. But even if the losses are confined to the 38 votes in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and California, Seward’s total would be 138, or 11 short of victory.

Thurlow Weed’s Apparent Electoral Math

| Electoral Votes | |

| Grand Total | 296 |

| Needed To Win | 149 |

| Sure Losses – Slave States | 120 |

| Left In Play | 176 |

| Republican Strengths | 114 |

| New England | 41 |

| New York | 35 |

| Ohio | 23 |

| Upper Midwest | 15 |

| Toss Up States | 62 |

| Pennsylvania | 27 |

| Indiana | 13 |

| Illinois | 11 |

| New Jersey | 7 |

| California | 4 |

Seward is not happy to hear the dire prognosis from Weed, but when it is also backed up by George Morgan, Horace Greeley and other political insiders, he decides to withdraw his name.

With Banks, Chase and Seward off the board, the spotlight shines on John C. Fremont. He grows up in South Carolina before joining the army and becoming famous for leading five trailblazing expeditions out west, the most recent in 1854. His exploits make him a national hero, Colonel Fremont, the American “Pathfinder” and commander of the “Bear Flag Revolt,” followed later by a brief stint as U.S. Senator from California.

Fremont’s latest political convictions are largely unknown, even to his supporters. His wife Jesse is the daughter of the Democratic Senator from Missouri, Thomas Hart Benton, and it is the disillusioned Democrat Francis Blair Sr. who prompts him to run. His credentials on slavery are thin, although he will eventually claim that he left the Democrats over repeal of the Missouri Compromise, and will be endorsed by abolitionists like Benjamin Wade and John P. Hale. Also on board are Know Nothings, most notably Nathaniel Banks and Schuyler Colfax.

Thurlow Weed also arrives at Fremont, viewing him much as his former “national hero” picks who were elected during his Whig years, Generals Harrison and Taylor. Like others, Weed also thinks Fremont has the Republican’s best shot at carrying Pennsylvania.

When the call goes out for nominations, only two men are offered up to the delegates, Fremont and McLean – and just before the first ballots are cast, a false rumor is spread that the Ohio Judge is about to withdraw his name. This only makes the results even more overwhelming in favor of Fremont.

First Ballot For President

| Candidate | Total |

| John C. Fremont | 530 |

| John McLean | 37 |

A few are dismayed by the choice, among them Horace Greeley, who has been hot and cold toward Fremont all along. In the end he calls him:

The merest baby in politics…not knowing the ABC’s and attributing importance to the most ridiculously insignificant matters and regarding the most vital of no account.

With Fremont chosen, what’s left for the convention is to pick a Vice-President. This sparks conflict between the Know Nothing contingent of “Seceders,” who feel they are “owed” the selection of Pennsylvania Governor William Johnston, and the Keystone state’s delegates, especially Wilmot and Stevens, who are violently opposed to him. When this split cannot be resolved, other options appear. One is Nathaniel Banks, but he is reluctant to resign as Speaker of the House to seek office, and delegates are reluctant to have two ex-Democrats on their ticket.

Another possibility is Abraham Lincoln, who will be put forward for national office here for the first time.

Lincoln has officially declared himself a Republican in advance of the convention. Given his Whig history, he leans toward McLean for the top spot, while declaring that he will stump for whoever wins the nomination. He does not attend the convention, and it is the Illinois delegation that offers him up for Vice-President on behalf of the western states. Cleverly they persuade John Allison of Pennsylvania to nominate him, as “the prince of good fellows and an Old-Line Whig.” Lyman Trumbull supports him as does an old state opponent, John C. Palmer, who says:

We (in Illinois) can lick Buchanan any way, but I think we can do it a little easier if we had Lincoln on the ticket along with John C. Fremont.

But the rally for Lincoln begins too late, as momentum builds behind William Dayton, ex-U.S. Senator from New Jersey, whose singular asset appears to be his potential to carry his home state. When the ballots are finally in, he joins Fremont on the ticket.

Vice-Presidential Votes

| Candidate | % Total |

| William Dayton | 65% |

| Abraham Lincoln | 14 |

| Nathaniel Banks | 6 |

| David Wilmot | 5 |

| Charles Sumner | 4 |

| All-Others | 6 |

The next stop for the Republicans will be to begin campaigning versus the Slave Power, while waiting to see whether the “hold-out Whigs” will run a third candidate in the election.

Their alliterative campaign slogan becomes: “Free Soil, Free Men and Fremont.”

September 17-18, 1856

The Pro-Union “Hold-Out Whigs” Back Millard Fillmore For President

Three months have passed since the Republican convention when the “Hold-Out Whig” delegates come to Baltimore on September 17-18, 1856 to select their presidential nominee. They are some 150 strong, and represent twenty-six of the nation’s thirty-one states, across the North and South.

The group includes many prominent national politicians who seek a stable, peaceful government capable of preserving the Union. On March 10 they have formally rejected an offer to merge into the Republican Party.

The delegates share a fear that the growing North-South divide over slavery will end with a break-up of the Union and possibly even a civil war. They also believe that the Republican’s open hostility toward the South as a whole (not just the 350,000 slave holders) will exacerbate this threat.

Most of the “hold-outs” come from the conservative wing of the old Whig Party, and they often express Know Nothing Party concerns over the dangers of Catholic immigrants who may owe their primary allegiance to a foreign power.

Many are also Fillmore men, among them his Secretary of State, Edward Everett of Massachusetts, his Attorney General, John J. Crittenden of Kentucky, John Bell of Tennessee, who attends the event, and Sam Houston of Texas — the latter two being the only two Southern senators voting against the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act.

The Party platform they settle on is one page long and consists of eight resolutions focused on their concerns over preserving the Union.

Resolved, That the Whigs of the United States are assembled here by reverence for the Constitution, and unalterable attachment to the National Union, and a fixed determination to do all in their power to preserve it for themselves and posterity

Resolved, That we regard with the deepest anxiety the present disordered condition of our national affairs. A portion of the country being ravaged by civil war and large sections of our population embittered by mutual recriminations, and we distinctly trace these calamities to the culpable neglect of duty by the present National Administration.

Resolved, That the Whigs of the United States have declared as a fundamental article of their political faith, the absolute necessity for avoiding geographical parties; that the danger so clearly discerned by the “Father of his Country,” founded on geographical distinction, has now become fearfully apparent in the agitation convulsing the nation, which must be arrested at once if we would preserve our Constitutional Union from dismemberment,

Resolved, That the only remedy for an evil so appalling is to support the candidate pledged to neither geographical section nor arrayed in political antagonism, but holding both in just and equal regard; that we congratulate the friends of the Union that such a candidate exists in Millard Fillmore.

Resolved: That…we look to him… for his devotion to the Constitution in its true spirit, and his inflexibility in executing the laws; but, beyond all these attributes, of being representative of neither of the two sectional parties now struggling for political supremacy.

Resolved, That in the present exigency of political affairs, we…proclaim a conviction that the restoration of the Fillmore Presidency will furnish the best if not the only means of restoring peace.

With the platform approved, it takes one ballot for the delegates to select ex-President Millard Fillmore to head their ticket, with Andrew Jackson Donelson in the second slot. Together they hope to present the nation with a middle way, a New Yorker and a Tennessee man, a Northerner and a Southern slave-holder, a synthesis of Whig, Democrat and Know Nothing.

Time will tell that the core sentiments expressed at this convention will live on right up to the opening salvos of war at Ft. Sumter in April 1861. They are the pleas of men who consider themselves patriots, sons of the founders, defenders of the Constitution, and heirs of Andrew Jackson’s devotion to one nation indivisible:

The Federal Union, It must be preserved.

It is Sam Houston who best captures the essence of what these “Whig Holdouts” stands for the other party options:

The Whig party lives only in the memory of its great name…The Democracy has dwindled down to mere sectionalism…It has lost the principles of cohesion and boasts no longer a uniform policy…It too has shown a disposition to court an alien influence to sustain it, while it has declared and practiced relentless proscription against Native Born Americans citizens.

Of the Republicans I can only say that their platform and principles are sectional and I cannot conceive how any man loving this Union …can support a ticket fraught with such disastrous consequences to the whole country.

A sense of duty… leads me to support… Fillmore and Donelson. They are good men, and I think the only men…who do most assuredly…claim the cordial support of…true hearted Americans, Democrats and Whigs. All faithful naturalized citizens, though of foreign birth, who cannot be controlled by any foreign influence, can come forward to their support as national men, capable and willing to support the Constitution and the Union.

Thus Fillmore and Donelson run as native born “national men,” intent on rising above sectionalism and maintaining the Union.