Section #4 - Early sectional conflicts over expanding slavery lead to the Missouri Compromise Of 1820

Chapter 41: The Marshall Court Issues Three Landmark Legal Rulings

March 16, 1810

In Fletcher v Peck The Supreme Court Overturns A State Law As Unconstitutional

Between 1801 and 1835 President Monroe, childhood friend, John Marshall, will lead the Supreme Court to a series of rulings that define and enforce the laws of the land.

In 1803 his ruling in the famous case of Marbury v Madison establishes the Supreme Court as final arbiter over the meaning of the articles and clauses in the 1787 Constitution

In 1810 the Fletcher v Peck dispute from Georgia finds the Supreme Court further asserting it authority — overturning a bill passed by a state legislature on the grounds that it violates the federal constitution.

The focus here is on “contract law,” with the facts of the case as follows.

After the Revolutionary War, the state of Georgia claims ownership of territory to its west, known as the Yazoo Lands or the Indian Reserve. This is a vast expanse, some 35 million acres in total, which will ultimately encompass the states of Alabama and Mississippi.

In 1795 land speculators hand over bribes to members of the Georgia state legislature to sell them the Yazoo lands for less than two-cents an acre.

When word of the bribery slips out, voters elect a new set of representatives in 1796, who pass a statute voiding the prior sale. Widespread confusion about ownership follows, and many lawsuits are filed.

One of these suits involves a parcel of 15,000 acres, sold by John Peck to Robert Fletcher, before the 1796 bill went into effect.

Fletcher still wants the land, but wishes to make sure that it is unencumbered by the 1796 statute. So he files a suit against Peck in 1803 to find out for sure.

After many back and forth rulings in lower courts, the suit finally reaches Marshall in February, 1810 – with the question focused on whether the 1796 state legislature acted legally in overturning the corrupt 1795 land sale.

The opinion is delivered on March 16, 1810, with Marshall summing up a unanimous 5-0 decision.

Despite the corruption surrounding the contract signed in 1795, the Marshall Court decides that the attempt by the 1796 legislature to overturn it violates Article I, Section 10, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution.

No State shall pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts.

This decision, favoring Peck’s claim of ownership, is the first time the Supreme Court declares that a state law must be voided because it is unconstitutional. It will not, however, be the last time that Marshall limits the power of the states.

February 2, 1819

The Dartmouth College v Woodward Decision Defines Rights For American Corporations

During Monroe’s presidency, several other High Court decisions will prove particularly impactful.

The first, in 1819, involves an attempt by the state of New Hampshire to take control over Dartmouth College, a private institution, by replacing its existing trustees with a slate of their own.

Dartmouth is founded in by a Congregationalist minister, Eleazar Wheelock, as a school for missionaries and Native Americans. A corporate charter, approved by the Royal Governor of New Hampshire colony in 1769, sets up two boards of trustees – one English and one American – to oversee college finances.

Wheelock dies in 1779 and is succeeded by his son, John, who encounters financial difficulties that threaten the viability and assets of the college. This prompts several, now American–only, board members to demand his resignation. When he refuses, they turn to Anti-Federalist members of the state legislature, who pass a bill converting Dartmouth from a private to a public school and naming a new set of trustees.

But others on the board oppose the change, arguing that, according to Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution, the government has no right to interfere with the operations of a private corporation.

In February 1817 they file a law suit against William H. Woodward, one of the original trustee dissidents, now serving as Secretary-Treasurer on the replacement state-sponsored board. The suit demands that the college be returned to private status, and that Woodward be compelled to return all records and seals, while also paying a $50,000 fine.

The Supreme Court of New Hampshire, however, rules in favor of Woodward – on the grounds that the school’s corporate charter was null and void after the Revolutionary War and independence from the Crown. This ruling is sufficiently important and controversial that the Marshall Court decides to review it.

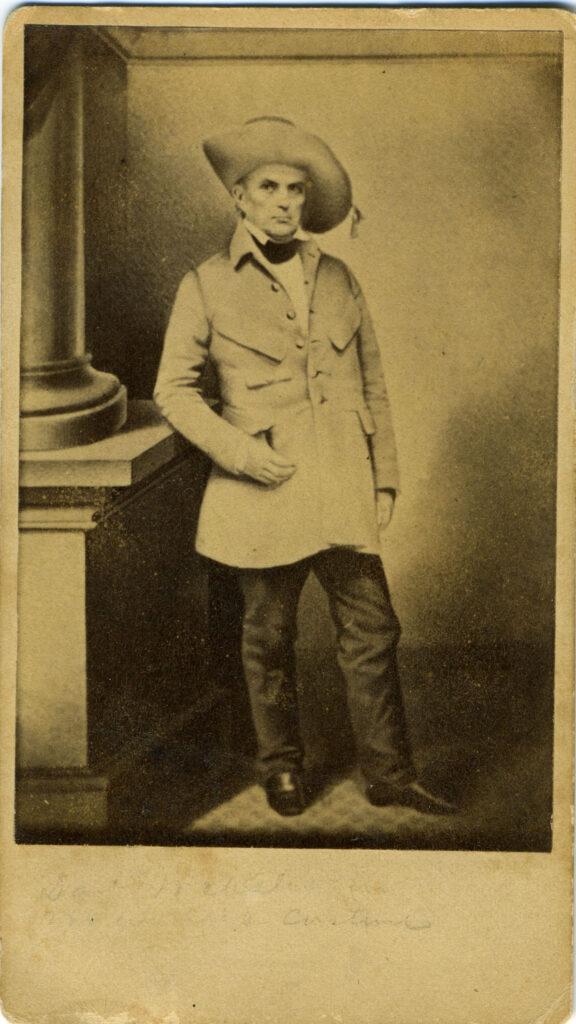

The plaintiff’s case is argued by Daniel Webster, at 37 years already regarded as the leading constitutional lawyer in America, and a former two-term member from New Hampshire in the U.S. House (1813-17).

Over time, Webster will argue some 223 cases before the Supreme Court, winning roughly half of them. In this instance, the matter is very personal to him, since he is an 1801 Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Dartmouth.

“Black Dan” Webster is forever an imposing figure in the courtroom and the halls of Congress, and his pleas ring with an emotional fervor that seldom fails to touch the minds and the hearts of his audiences. This is again the case in his summation to the Chief Justice about Dartmouth:

This, sir, is my case. It is the case not merely of that humble institution, it is the case of every college in our land… Sir, you may destroy this little institution; it is weak; it is in your hands! I know it is one of the lesser lights in the literary horizon of our country. You may put it out. But if you do so you must carry through your work! You must extinguish, one after another, all those greater lights of science which for more than a century have thrown their radiance over our land. It is, sir, as I have said, a small college. And yet there are those who love it!

By a 5-1 majority, the Supreme Court comes down in favor of Webster and the inviolability of Dartmouth’s corporate charter, albeit originally signed with King George III.

This ruling will have a profound effect on the evolution of “private corporations” in America.

It establishes the principle that private corporations are allowed to operate in their own self interest rather than on behalf of the state.

They cannot act in violation of state or federal laws. But they have the right to pursue their own ends – for example “adding to the wealth of their shareholders” – without arbitrary or frivolous interference from government.

In 1825 the Court will re-visit the rights of corporations in: The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts v Town of Pawlet. Here the state of Vermont tries to revoke land grants held by an English corporation dedicated to Christian missionary work in America.

Again, the Marshall court sides with the corporation against the state.

Writing for the majority, Justice Joseph Story concludes that corporations enjoy the same rights to their property that are enjoyed by everyday citizens.

Over time, Story’s analogy between the rights of individual people and corporations – literally a “body of people” – catches hold as a precedent in common law.

In 1832, Marshall picks up on Story’s analogy in defining another characteristic of corporations, namely their right to exist beyond the lifetimes of their original founders.

The great object of an incorporation is to bestow the character and properties of individuality on a collective and changing body of men.

The principle that corporations have the right to establish their own charters, to possess property and to endure across generations becomes a driving force in the development of private businesses and economic growth in America.

Backed by a 5-1 majority, Marshall argues that a corporate charter is a “contract” and, as such, it cannot be arbitrarily breached by the state.

March 16, 1819

The McCulloch v Maryland Decision Declares That Federal Laws Trump State Laws

Six weeks after the Dartmouth College decision, on March 16, 1819, the Marshall court again reins in the power of individual state legislatures.

This time the state in question is Maryland, and its adversary is none other than the federal government itself.

The dispute arises when the Second Bank of the United States decides to operate a branch in the city of Baltimore, and the Maryland legislature passes a bill to collect a state tax on transactions done by the bank.

The head of the US Bank, James McCulloch, refuses to pay the tax, and goes to court to affirm the legality of his refusal. But the Maryland Court of Appeals not only rules against McCulloch, it also declares that the federal government had no right under the Constitution to even charter a Bank of the United States in the first place.

According to Maryland, the Constitution says nothing about the federal government’s role in establishing bank charters, and, therefore, under the Tenth Amendment, it is the “state’s right” to act as it sees fit.

Here indeed is a constitutional question around defining federal vs. state powers that is worthy of the Supreme Court’s closest scrutiny.

In the final ruling, backed by a 7-0 majority, Marshall opens the door to a broad interpretation of the powers the founders intended to place in the hands of the federal government.

He first observes that no single document could be expected to provide a list of enumerated powers sufficiently detailed and comprehensive enough to cover all issues coming before the courts.

From there he zeros in on Article 1, section 8, clause 18 of the Constitution and the notion that the federal legislature has the power to pass whatever laws it deems “necessary and proper” to fulfill its duty to the citizens.

The Congress shall have power to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution…the powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States.

But what is “necessary and proper” when it comes to banking?

For the Marshall court, it is whatever the voice of the people deem it to be when the issues are debated and voted upon by their representatives in Congress.

Thus the fact that the first session of Congress found it “necessary and proper” to charter the First Bank of the United States provides a sound precedent for the legitimacy of a Second U.S. Bank.

Finally, the decision to charter the U.S. Bank was reached at the national level, by majority rule, after all sides had a chance to make their arguments pro or con. Surely the voice of the people operating together as a unified nation deserves to trump the voice of any one dissident state.

So Marshall and his colleagues side unanimously with McCulloch over Maryland.

For the Jeffersonians, this decision threatens their wish to limit federal powers via the Tenth Amendment.

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

If the Congress in D.C. gets to decide what is “necessary and proper” when it comes to setting up bank charters, what else might follow from this precedent?

For many Southerners, the focus turns immediately to “the future of slavery.”

Yes, the right to own slaves within the 1787 boundaries of the United States is expressly stated. But does that right extend automatically to new land, such as the Louisiana Territory, acquired after the original contract between the states?

Or, based on this Marshall Court principle, will the Federal legislature claim that it is “necessary and proper” for this decision to rest on their shoulders?

If so, many Southerners begin to see the Federal legislature as a clear and present danger to their economic prosperity. What would happen to future “demand” for their cotton and their slaves if the U.S. Congress decided to “contain slavery” within its original boundaries rather than allow it to spread across the Mississippi River?

In 1820 that question will move from idle speculation among wealthy planters to center stage on the floor of Congress.