Section #14 - Anti-Slavery sentiment grows due to the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Chapter 175: The March Is On To Build A Trans-Continental Railroad

As Of 1853

No Fast Transport To The West Coast Exists

Passage of the March 3, 1853 appropriation to explore routes for a transcontinental railroad recognizes the economic necessity of finding a better way to transport goods and services between the east and west coasts.

The existing options are two-fold — one by sea around Cape Horn, the other cross country by wagon train or stage coach. Both are seriously flawed.

The nautical route is well known and dominated by 200 foot long clipper ships, with their three squared-rigged masts reaching 115 feet into the sky. But their sleek lines cannot overcome two serious drawbacks — the first being the 200 days required to complete the 16,000 mile route from New York and around South America to San Francisco. In addition, this journey is also fraught with peril, especially at Cape Horn, known as the “sailor’s graveyard” for its unpredictable gale force winds and icy winter conditions. Merchants with large loads will still choose this shipping option, but always with trepidation.

The feasibility of moving sizable quantities of material and people by wagon trains into the west is demonstrated by the US Army during the 1846-47 Mexican War, and again by the great Mormon trek from Iowa to Salt Lake City in 1847. But here too the drawbacks include speed and risk. Thus the early Mormon caravan of seventy-five wagons and 300 men takes upwards of six months just to travel 1,250 miles through winter weather and tribal frays, from Nauvoo, Illinois to their new home in Utah.

Transportation of people and small parcels in the 1850’s is more streamlined, thanks to the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach line, later acquired by the Wells Fargo Corporation. This operation transports mail and passengers over 2,795 miles from St. Louis through Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, to San Francisco in 25 days, fulfilling its contract with the U.S. Postmaster General. This feat is accomplished by 4-6 horse teams racing at top speed between some 141 stop-over stations scattered along the route. While remarkably fast for their time, stagecoaches are unable to transport the heavy loads demanded by commerce.

When congress sets aside $150,000 to survey the west, it is betting that a transcontinental railroad will deliver on the speed, load weight, safety and pricing required by the emerging industrial and global economy.

As Of 1853

Railroads Are Already Succeeding In The East

By 1853, railroads are already an established part of the landscape back east.

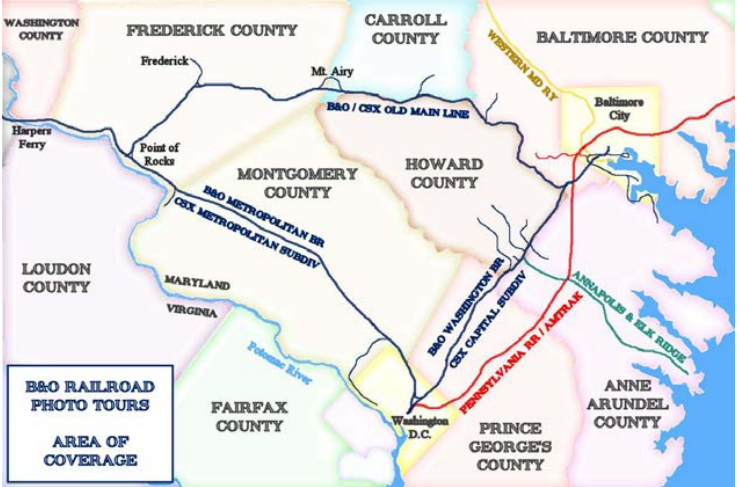

They begin to take hold in the 1830’s, as the prototype B & O line moves goods from the port city of Baltimore, inland across Maryland in competition with the Erie Canal — the 363 mile east-west colossus linking Buffalo on Lake Erie to Albany and ultimately to New York City.

By 1852, the B&O has pushed on to Wheeling, Virginia, before turning north toward the Ohio River at the city of Parkersburg. Five years later, a series of railroad mergers will carry the B&O all the way through Cincinnati to St. Louis and trade along the Mississippi Valley.

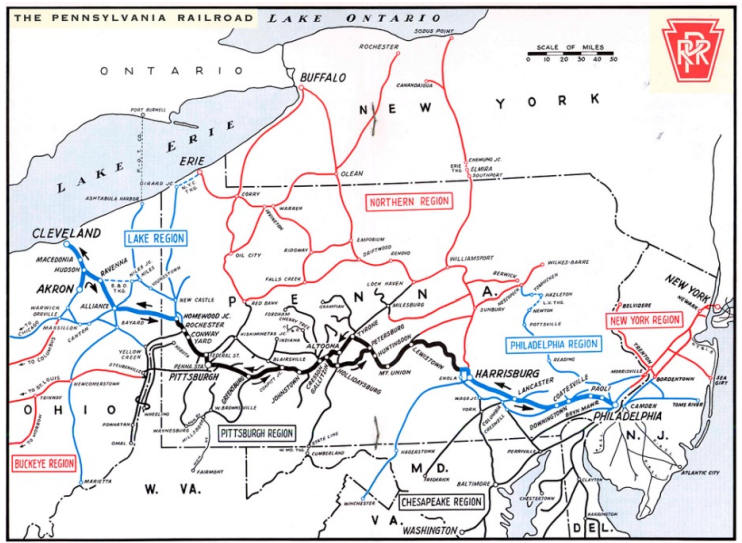

During this same period, the industrialist and civil engineer, J. Edgar Thomson, is busily extending his Penn Central Railroad toward Indiana and Chicago. His venture, founded in 1847, will become the largest corporation in the world for a time, and he will earn the title “father of the modern railroad network.”

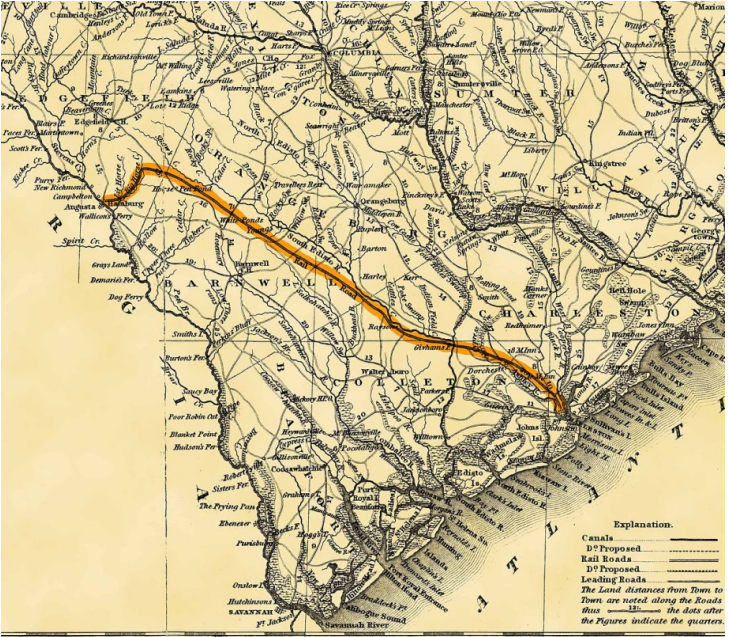

The South trails well behind the North in railroad construction, but does begin to engage. In 1833, the Carolina Canal and Railroad Company, headed by William Aiken Sr., completes a 136 mile connection between Charleston and Hamburg, SC. Three years later it merges with a firm incorporated under the ambitious name of the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Railroad, headed at the time by the former South Carolina Senator, Governor and renowned “Fire-Eater,” Robert Hayne. He will be succeeded in 1840 by James Gadsden, later the leading proponent of the 32nd parallel “Southern route” to the pacific.

While the various eastern lines are heading west, new railroads are also starting up in states along the Mississippi Valley — their mission being to facilitate local commerce, while also contending for a major role in the inevitable drive across the continent.

Given the investment costs required to lay track, buy cars and manage daily operations, mergers become commonplace in the industry, along with sharing of facilities. Symbolic of the consolidations is the nation’s first “Union Station,” which opens on September 3, 1853 in Indianapolis, to serve multiple lines.

Between 1840 and 1860 the great American train race is under way, with a tenfold increase in the miles of tracks in operation, and seventeen of the largest twenty-five corporations in 1856 in the railroad sector.

Accumulated Miles Of Railroad Tracks By Region

| Geography | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 |

| Total U.S. | 40 | 2,755 | 8,571 | 28,680 |

| New England (Me,NH,Vt,Ma,RI,Ct) | 30 | 513 | 2,596 | 3,644 |

| Rem. North (Del,NY,NJ,MD,DC,Oh,Mi,In) | — | 1,484 | 3,740 | 11,927 |

| West (Il,IA,Wis,Minn,MO) | 46 | 4,951 | ||

| South/Border (Va,NC,SC,Ga,Fl,Al,Ms,Ky,Tn,La) | 10 | 758 | 2,189 | 8,158 |

As Of 1853

The Illinois Central Railway Is The Longest Line In The Nation

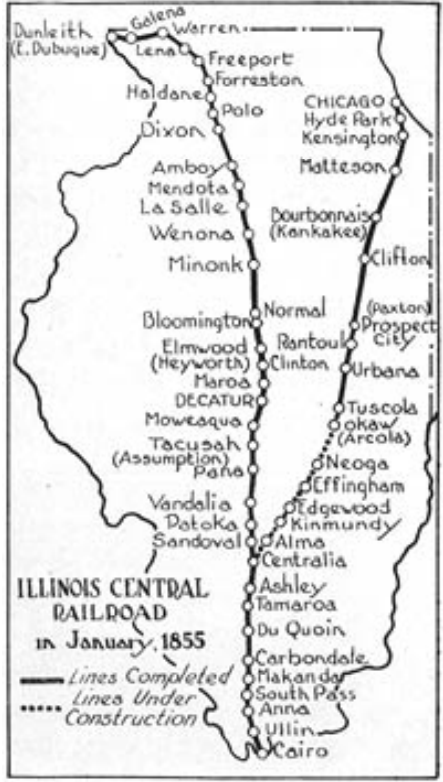

The dominance of the B&O and Penn Central railroads in the East is matched in the Midwest by the Illinois Central line, the first to take advantage of Washington’s 1850 Land Grant.

The ICRR is chartered on February 10, 1851, and by 1853 it stands as the longest rail line in the entire world.

One leg of the IC runs from the lead mining town of Galena on the Mississippi down to the city of Cairo, also on the great river; a second leg is under way to connect Chicago to a junction at Centralia and from there to Cairo.

Two men influence the growth of the Illinois Central over time – one, Senator Stephen Douglas, its cheerleader in Congress, the other, attorney Abraham Lincoln, who handles most of its affairs in court.

Both regard their home state as somehow fated to play a strategic role in developing the west and linking it to the east, owing to its unique geography.

Thus Illinois lies toward the center of the country on its horizontal axis, and, being long and narrow, runs vertically nearly 400 miles down to its southern tip, nestled between the slave holding states of Kentucky and Missouri. As such, Illinois will often be regarded as two states in one, half northern and half southern.

Also, of great importance, the state’s northeast border is anchored in Chicago on Lake Michigan, which enables it to handle heavy duty commercial traffic arriving from the east by both train and water. Douglas recognizes this advantage in a January 20, 1851 letter to former Illinois Senator and colleague, Sidney Breese, in relation to building a transcontinental line:

It is necessary that the (rail)road should connect with the lakes in order to impart nationality to the project and secure Northern and Eastern votes.

All that Illinois lacks in 1853 is a rail line heading west from Chicago, connecting the two legs of the ICRR, and then heading west all the way to California.

If Douglas can only get the senate on board behind his Nebraska Bill, and then lobby effectively for the trans-continental train route through Illinois, he will realize his grand “Young America” vision for the Mississippi Valley and the west. It will be linked back east by train tracks and telegraph lines and boast a diverse and modern economy, amenable to rural life and farming, but also marked by large urban centers, factories and associated “wage jobs.”

All with the state of Illinois and the city of Chicago becoming the central hub in this development, funneling commercial traffic throughout America, east and west, north and south.

Sidebar: The Two Springfield Lawyers With Deep Financial Ties To The IC Railroad

Two Springfield attorneys, Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln, will become heavily dependent upon the Illinois Central Railroad for their personal wealth.

In Douglas’ case, this traces to his extensive speculation in land around Chicago, which the ICRR will eventually need to purchase as its “right of way” to lay tracks.

By 1852 he will own 75 acres of this land along the lakefront, south of the city. He also purchases several thousand acres to the west, and additional plots on the south branch of the Chicago River and around Lake Calumet.

In 1855 he recalls paying roughly $11,300 in total for these properties.

His return on this investment is remarkable. In 1856 his first 75 acres are already valued at $60,400 for tax purposes, and the ICRR soon pays him $21,300 for only a few of the acres situated on the lake. In that same year he sells 100 of his acres on the west side of the city for $100,000, and another 16 acres along the lake for $20,000.

Douglas’s wealth is supplemented by profits from a 3,000 acre cotton plantation on the Pearl River in Mississippi that his first wife, Martha Martin, inherits as a wedding gift from her father. The plantation is valued at $100,000 and is worked by some 140 slaves. For political reasons, Douglas is careful to keep ownership in the name of his wife, and later their children. While he makes only three personal visits to the plantation, he hires and corresponds regularly with a local manager, Richard Strickland, and enjoys a 20% share of the annual profits.

Douglas will continue to speculate in land and to lead an extravagant lifestyle. The combination leaves him land rich but cash poor in the end and results in mortgages against his Chicago area land and a trade-down to a lesser plantation in Mississippi soon before his death.

Like Douglas, Abraham Lincoln is also deeply involved in the affairs of the ICRR. In 1853 Lincoln is busily practicing law in Springfield, punctuated by stints in politics.

But during his time in the Illinois legislature, and in his one term (1847-9) in the U.S. House, he consistently votes to fund and construct a railroad system running across his home state. As a private citizen, he also earns his living as a lawyer, with the Illinois Central line by far his leading client. Between 1853 and 1861 Lincoln represents the ICRR on literally hundreds of cases in suits involving rights of way, property damage, trespass, taxes and freight claims. He will argue eleven of these disputes in front of the Illinois Supreme Court – earning his reputation as one of the top attorneys in the state, and also connecting him to a broad array of capitalists and political figures.

Perhaps his most famous case is Illinois Central Railroad Company v County of McLean (IL) and George Parke, Sheriff and Collector. The county sits in the middle of Illinois, with depots serving several scattered towns.

In 1852 the county decides to challenge the incorporation charter which says that if the IC pays a share of its revenue – 5% for the first five years and 7% for the next five – to the state, it will be exempt from all other forms of taxation.

It does so by attempting to levy a separate property tax on the line, involving a fairly modest payment of $418. But the IC recognizes that submitting to the McLean charge will open the taxing floodgates for other localities across the state. It therefore refuses to pay, at which time the tax collector, George Parke, threatens to auction off IC land to collect the debt.

The IC responds by retaining Lincoln, for $250, along with two other lawyers to defend the legality of the charter in court. An injunction is filed to halt Parke’s planned auction, and a local trial is held in November 1853 before presiding Judge David Davis – who, seven years hence, will become one of Lincoln’s floor managers at the Republican nominating convention.

When Davis finds for the railroad, McLean refuses to give up and appeals the case all the way to the Illinois Supreme Court. Lincoln argues there on behalf of the IC in February 1854 and a second time in January 1856, as the case drags on. But again the IC wins a major victory.

What follows next makes the case linger in historical lore. Lincoln submits an uncharacteristically large bill — for $5,000 — to the IC, perhaps in response to some forever unknown falling out during the case. Several corporate stockholders in the IC, particularly in England, refuse to pay the amount, commenting that the Governor of Illinois earns only $1,000 and year, and “not even a Daniel Webster” would charge that much.

In response, Lincoln sues the IC, and wins the judgment in June 1857 when no railroad lawyers show up at the scheduled trial. Lincoln will use his windfall fee to fund his upcoming political campaigns. He will also continue his involvement with the IC after the dispute.

(Research into Lincoln’s finances by modern scholars show that his other two largest legal bills were $500 in the 1855 Rock Island RR Bridge case and $1,000 in the 1857 “Reaper Case.”)