Section #19 - Regional violence ends in Kansas as a “Free State” Constitution banning all black residents passes

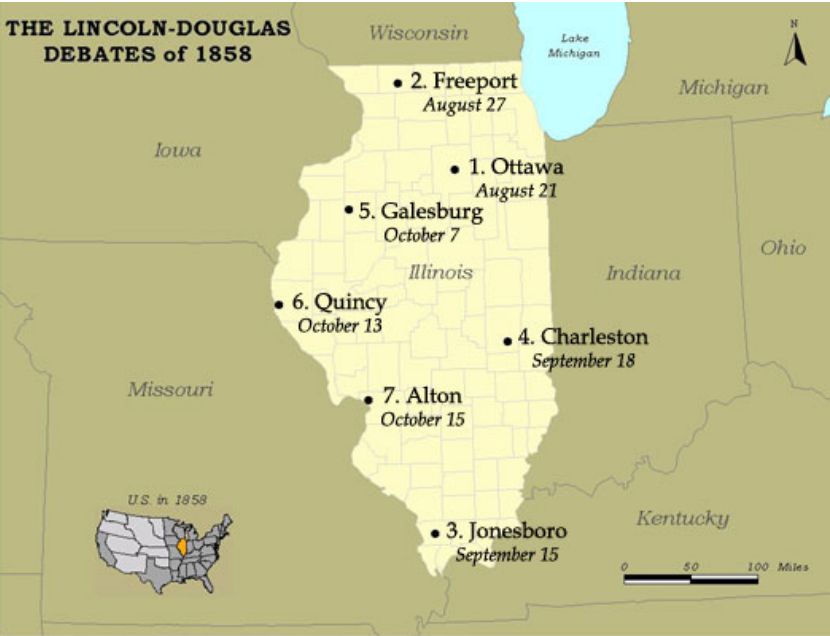

Chapter 232: The Lincoln – Douglas Debates Frame The National Divide Over Slavery

August-October 1858

The Stage Is Set For The Debates

In an eight week period from August 21 to October 15, 1858, the spotlight on the national debate over slavery is focused on Illinois, where the upstart Republican, Abraham Lincoln, is running for the U.S. Senate seat against the incumbent Democrat, Stephen Douglas. Lincoln has tried once before, in 1855, and failed. Douglas has been elected twice and is seeking his third term.

After winning the nomination on June 16 and delivering his famous “house divided” acceptance speech, Lincoln begins chasing Douglas from one campaign stop to the next, following up his speeches with rebuttals delivered to the same audiences. This irritates Douglas, and the two men finally agree to hold seven joint appearances across the state. Each will be divided into three segments: the first speaker to open for one hour; his opponent to respond for ninety minutes; then a closing half hour rebuttal for the initial speaker. The honor of going first will be rotated from one location to the next.

Given the nationwide interest in the debates, stenographers are present on stage to try to capture the words spoken so that newspapers can report on the news from each exchange. The actual live audiences vary by city and by weather conditions, ranging from a low around 2,000 in Alton to over 10,000 in several other venues.

The typical debate takes place in the town square, beginning in the early afternoon hours. The speakers appear on a raised platform, with the crowds gathered around them, standing throughout the event, often straining to hear their messages. Those who record the experience remark on the marked contrasts between the speakers.

The difference in their heights and physical builds seems almost comical. Lincoln is 6’4” tall, rail thin, and gangly in his posture. Douglas is a foot shorter, hardly coming up to Lincoln’s shoulder, with a thick frame and an oversized head held erect at all times. Lincoln is dressed in a plain black suit, while Douglas is decked out in a dark blue coat, light pants, a ruffled shirt, topped off by a broad-brimmed white felt hat.

When Lincoln opens his mouth to speak, the audience is greeted with a Kentucky twang, particularly high pitched until early nervous tension is overcome. He is also inclined to punctuate his main points with…

One single gesture delivered with his right forefinger (that) seemed to be continuing to scratch away in front of (him).

On the other hand, Douglas owns the deep baritone of a theater actor, booming out his message in rapid order and with unwavering self-assurance and clenched fist pointed skyward.

Both men are highly skilled and experienced lawyers, blessed with logical minds and the capacity to frame and deliver their arguments in cogent fashion. Lincoln is prone to injecting humor into his remarks, and to speaking in emotional terms about slavery. Douglas is all business, pounding home his points and refraining from even mentioning his feeling about those enslaved.

Each is backed by advisors, who help the candidates understand the challenges they face and plot their messages along the way. Lincoln envisions two audiences for his remarks: the live audience at each venue and the newspaper-reporters whose stories will broaden his reach. As such, he tends to vary his main points from one town to the next, building his case in cumulative fashion. On the other hand, Douglas seldom varies from his main script, relying on repetition and the power of his oratory alone to persuade the attendees in front of him.

Both men, however, are prone to wander into legal complexities and jargon that is lost upon their audiences.

August-October 1858

The Opponents Settle On Their Strategies And Messages

The future of slavery is what draws the sizable turn-outs, and both candidates focus almost exclusively on this issue, choosing to ignore possible differences on the financial crisis, immigration policies or other matters.

Attitudes toward the institution itself vary across the 420 mile vertical axis where the debates are held, from Freeport, up north near Chicago, to Jonesboro, nestled south in “Little Egypt” between Kentucky and Missouri.

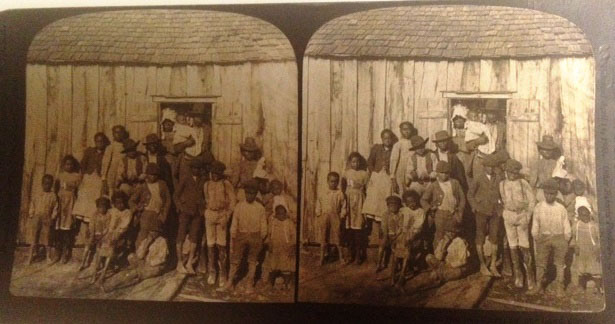

But one thing that doesn’t vary across Illinois is absolute opposition to allowing any more blacks – be they slaves or freedmen – to come into their communities. This conviction is based on long-entrenched negative stereotyping of all negroes. It is evident in state constitutions across the North, the most recent example being in Kansas, where the Topeka legislature adopts an “Exclusionary Clause” banning blacks from residence, cheek to jowl with their wish to be designated as a “Free State.”

While Lincoln exhibits much less racial prejudice than most Americans, his public policy pronouncements happen to fit well with this desire to “keep blacks out.”

If, as he says, the Dred Scott ruling opens the door to “nationalizing slavery,” including in Illinois, then at least his proposed federal ban is the best way to try to prevent that outcome.

Douglas is a crafty enough politician to see that his alternative to a ban – “let the people decide” – is nowhere near as definitive as Lincoln’s proposal. Thus his challenge in the debates will lie in attacking him from a different angle.

He does so by painting Lincoln, and all Black Republicans, as radical Abolitionists in disguise.

Thus while banning the spread of slavery, he implies that Lincoln will turn around and free all of the Southern slaves and allow them to settle anywhere they want, as freedmen. According to Douglas, Lincoln also regards negroes as equal to whites, intends to hand them the right to vote, even to encourage inter-marriage between the races. Worse yet, the result of all this will be the end of the Union and perhaps a civil war.

Lincoln vigorously denies the abolitionist tag and says that freeing Southern slaves is legally prohibited by the 1787 Northwest Ordnance. But he also argues that the nation’s founders wanted slavery to wither away, regarding human bondage as a moral stain, and inconsistent with the values announced in the Declaration of Independence.

Douglas will fire back, insisting that America was founded by and for the white race, and that emotional pleas about the morality of slavery should carry no weight in the debates. The central question, he says, is whether the future of slavery should be decided by votes cast by people living in the territories or by federal mandates from Lincoln and his abolitionist Republican allies.

August 21, 1858

The First Debate In Ottawa Opens With Douglas As Aggressor

Douglas brings several advantages to the contest, and intends to exploit them all. He has been an Illinois Senator for eight years and the state is rightly proud of his reputation as a powerhouse on the national stage. His Democratic Party enjoys a majority in the state legislature – where the final votes will be cast – going into the Fall. He also feels that his years in the political arena make him a better debater than Lincoln.

The opening debate unfolds on August 21, 1858 at the town of Ottawa, in upstate Illinois, some 85 miles southwest of Chicago. A sizable crowd over 10,000 strong shows up at Lafayette park to hear the exchange, which begins around 2:30pm, with Douglas leading off. The Little Giant immediately goes on the offensive.

His goal is to peg Lincoln as an Abolitionist who will free all slaves and let them loose to invade the North and the new territories to the west. To prove this, he holds up what he claims is a radical “party platform” that Lincoln supposedly signed in Springfield calling for:

- A total repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act

- Abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia

- Prohibiting interstate sales of slaves

- Prohibiting the presence of slaves in all new territories

- Refusal to admit any more Slaves States into the Union

- Refusal of any further acquisition of new territory

- Denying the right of new states to create a constitution of their own

Within days this “Springfield platform” document will be debunked as the work of an obscure abolitionist meeting held in Aurora, Illinois, and nothing to do with Lincoln. This “error” by Douglas is evidently an honest one, but it is nevertheless an embarrassment for him.

For the moment in Ottawa, however, he demands that Lincoln respond by saying whether he agrees or disagrees with each of the assertions.

Lincoln is caught off guard by this tactic. He claims, properly but in awkward fashion, that he never heard of this “Springfield document” and refuses to answer the particulars. Instead he falls back on rehashing his 1854 Peoria speech, where he attacked Douglas for his Kansas-Nebraska Bill.

Once he regains his balance, Lincoln appeals to his mostly Northern audience to oppose the “monstrous injustice of slavery” which violates the “fundamental principles of civil liberty.”

I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world – enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites – and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty – criticizing the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.

As usual throughout the debates, Douglas brushes the “morality appeal” aside as a red herring, an attempt by Lincoln to insert emotion into what should be decided by reason.

I desire to address myself to your judgment…and not to your passions or your enthusiasm.

Opinions vary as to who prevails at Ottawa, but Lincoln’s performance immediately advances his political stature both in Illinois – where until now he has been a little known “down-stater” – and at the national level. His advisors urge him to be even more aggressive going forward:

Don’t act on the defensive at all…be bold, defiant and dogmatic…in other words, give him hell.

August 27, 1858

Lincoln Corners Douglas On Popular Sovereignty In Freeport

The two combatants meet again after a six-day hiatus, this time in upstate Freeport, a stronghold for Republicans in the 1856 presidential race. Most observers agree that Lincoln turns in a strong performance here.

He leaps directly into answering the seven questions Douglas posed in Ottawa.

- I do not favor the unconditional repeal of the fugitive slave law.

- I do not stand pledged against territories which wanted slavery after they became states.

- I do not stand pledged against the admission of territories as slave states if it comes when the seek admission.

- I do not stand pledged today to abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia.

- I do not stand pledged to prohibit the interstate slave trade.

- I am not generally opposed to honest acquisition of new territories.

But he says that, in accord with the wishes of the founders and of common humanity:

I am pledged to a belief in the right and duty of Congress to prohibit slavery in all the United States Territories!

He also takes the opportunity to chastise Douglas for using a mistaken document to frame his questions at Ottawa in the first place, saying it was…

Most extraordinary (to) so far forget all the suggestions of justice to an adversary, or of prudence to himself, as to venture upon (his) assertion…which the slightest investigation would have shown him to be wholly false.

With that out of the way, he turns the tables on Douglas with four interrogatories of his own.

- Would he favor acquiring more foreign land even if it included slaves?

- Would Douglas just admit Kansas before it has the 93,000 residents required by law?

- Could a territory exclude slavery by law before it becomes a state?

- Did he agree with the Dred Scott ruling that a state cannot exclude slavery?

The first question intends to show Douglas’s personal commitment to slavery. Lincoln knows that Douglas owns slaves himself, and that he supports the acquisition of Cuba and more land in Mexico and Central America that would expand the reach of slavery – and he wants this on the record. The others are aimed at challenging the theory and practice of popular sovereignty, and driving a further wedge between Douglas and those Democrats who back the Buchanan administration.

The most telling question in this second debate, and probably across all seven, calls upon Douglas to square the Supreme Court dictates in Dred Scott with his policy of popular sovereignty. When the high court decrees that slave owners must be allowed to take their property to any state or territory they want, doesn’t this overrule any votes cast expressing the wishes of local residents?

Douglas responds with what will become known as his “Freeport Doctrine:”

It matters not what the Supreme Court may hereafter decide as to the abstract question whether slavery may or may not go into a territory under the Constitution, the people have to lawful means to introduce it or exclude it as they please, for the reason that slavery cannot exist a day or an hour anywhere, unless it is supported by local police regulations. Those police regulations can only be established by the local legislature, and if the people are opposed to slavery, they will elect representatives to that body who will by unfriendly legislation effectually prevent the introduction of it into their midst. If, on the contrary, they are for it, their legislation will favor its extension.”

Here is the classical argument made by supporters of state’s rights (or sovereignty) ever since the 1803 Marbury v Madison finding that federal laws trump local laws. John Calhoun tries to resist the 1828 Federal Tariff increase by having South Carolina “nullify” the law. Lincoln now accuses Douglas of employing this same tactic on slavery.

While Lincoln can claim a victory among constitutional scholars for this challenge, it seems likely that bringing up the conflicts between Dred Scott and popular sovereignty hurts him in the Senate race. For sure it allows Douglas to claim that his policy remains a viable alternative for Illinois voters who wish to “keep blacks out” absent a federal ban.

Ironically the “Freeport Doctrine,” which ends Douglas’ prospects for becoming president as a Democrat, spurs speculation that he might eventually run as a Republican!

September 15–18, 1858

Douglas Forces Lincoln To Discuss His Racial Views At Jonesboro And Charleston

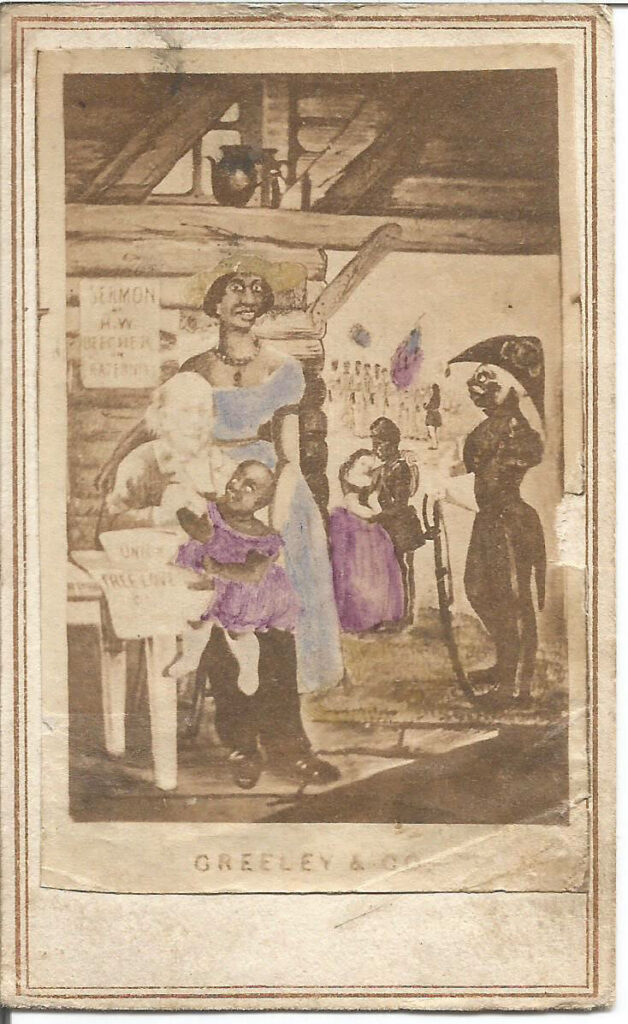

Case Leveled At Abolitionist Horace Greeley

Douglas uses the third and fourth debates to pressure Lincoln on his beliefs about the “all men are created equal” tenet, and whether it applies to the negro race.

On September 15, 1858 the two meet at the small town of Jonesboro, the southernmost stop on their circuit, and the most inclined to be pro-slavery. The crowd numbers only 1,500, and the speeches are largely a rehash of points made earlier. Lincoln jabs again at the seeming irrelevance of popular sovereignty after the federal ruling in Dred Scott. Douglas asserts that…

The signers of the Declaration of Independence had no reference to the negro whatsoever when they declared all men to be created equal.

Three days later, an enthusiastic assembly of 12,000 spectators show up at Charleston, along the border with Indiana, for the fourth exchange. As part of the preliminary fanfare, Douglas supporters mount a large banner showing a white man, a black woman and a mulatto child, titled “Negro Equality.”

Lincoln spots this display and recognizes its intent to label him as an abolitionist and a supporter of miscegenation. He decides to address these claims head on as the opening speaker. His comments are remarkably candid in revealing his lifelong struggle with what to do about slavery.

He says that he has always regarded it as immoral and a violation of American values, but continues to be perplexed about finding a practical solution. He cannot imagine that the differences between the races, and the negative stereotypes of blacks, will ever support assimilation.

There is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together, there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.

He then dismisses Douglas’ charges that he supports racial equality, and inter-marriage:

I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the black and white races….I am not, nor ever have been, if favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, not to intermarry with white people…I do not understand that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife.

Some of his supporters will later express shock at these remarks, which they regard as racial pandering.

He forsook principle and planted himself on low prejudice…The Negro had no stauncher advocate than Lincoln…(but) now that same Lincoln declared that the Negro, created as a race inferior to White by the Lord Almighty, must remain in his condition.

Lincoln is careful here, and elsewhere, to not blame the people of the South for the problem, to not refer to the entire region as the “Slave Power.” As a follower of Clay, he says he would favor re-colonization of all blacks, while acknowledging that the economy could not support that path. What’s left then is to follow the founder’s wishes, and at least refuse to let the practice expand.

Moving along, he spends the remained of his opening comments on a new and questionable charge, saying that Douglas plotted to avoid a public vote on the Lecompton Constitution in Kansas.

Now, the charge is, that there was a plot entered into to have a Constitution formed for Kansas, and put in force, without giving the people an opportunity to vote upon it, and that Mr. Douglas was in the plot.

This attack originates with Douglas’ mortal enemy, Lyman Turnbull, the junior Senator from Illinois, recently converted from a Democrat to a Republican. The Little Giant dismisses the charge, saying that he has staked his entire political future on popular sovereignty. He also mocks Lincoln for bringing it up.

Why, I ask, does not Mr. Lincoln make a speech of his own instead of taking up his time reading Trumbull’s speech?

Douglas goes back on the offensive, with his contention that Lincoln and the Republicans are all abolitionists.

No sooner was the sod grown green over the grave of the immortal Clay, no sooner was the rose planted on the tomb of the Godlike Webster, than many of the leaders of the Whig party, such as Seward, of New York and his followers, led off and attempted to abolitionize the Whig party, and transfer all your old Whigs bound hand and foot into the abolition camp.

He also calls Lincoln’s patriotism into question over his reservations about the Mexican War.

If Mr. Lincoln is a man of bad character, I leave you to find it out; if his votes in the past are not satisfactory, I leave others to ascertain the fact; if his course on the Mexican war was not in accordance with your notions of patriotism and fidelity to our own country as against a public enemy, I leave you to ascertain the fact.

Finally, he accuses Lincoln of telling one audience that blacks are equal to whites, and then denying this for the next – depending on what he thinks they want to hear. Lincoln parries and the debate comes to an end.

September 18, 1858

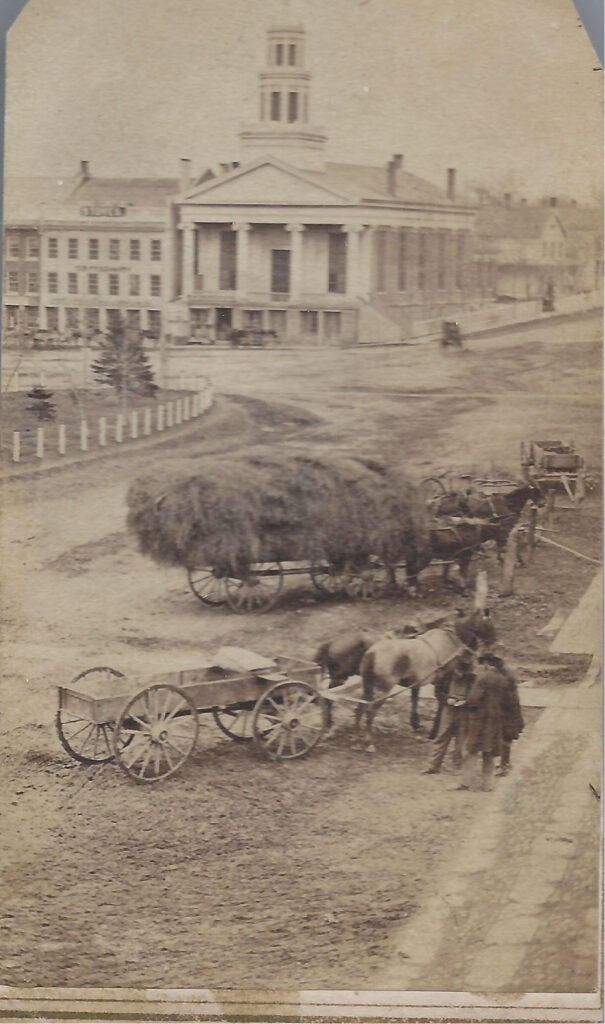

Sidebar: The Atmosphere At The Charleston Debate

Saturday, September 18, 1858 would go down as the most exciting day in the history of Charleston, Illinois. It pitted “Honest Abe, the Tall Sucker” against “The Little Giant,” and corn farmers from nearby Muddy Point, Dog Town, Muddy Point, Pinhook, and Greasy Creek poured into town by horseback, wagons and trains, loaded down with food and cider.

Many folks are decked out in colorful costumes marked by campaign buttons and ribbons. Bands play and parades feature floats, often with elaborate praise for their favorites.

Westward the Star of Empire Takes its Way, Our Girls link-on to Lincoln, Their Mothers were for Clay.

The Douglas procession includes sixteen young couples on horseback carrying American flags and offering huzzas:

The Government Made for White Men-Douglas for Life

Both men encounter negative banners, one showing Douglas being clubbed to the ground by Lincoln, the other a “Negro Equality” sign that Lincoln addresses as he opens.

The speakers address the crown from a raised platform, 18 feet by 30 feet, large enough to seat some sixty special guests, among them Mrs. Douglas in an elaborate lavender dress, but not Mrs. Lincoln, who does not attend. With such a large crowd. Lincoln begins by encouraging silence along the way.

It will be very difficult for an audience so large as this to hear distinctly what a speaker says, and consequently it is important that as profound silence be preserved as possible.

Despite the admonition, supporters are inclined to cheer loudly for their favorites, while opponents interrupt occasionally with their own catcalls and challenges. The event carries on from 2:45pm to the conclusion around 5:15pm. At that time, both candidates retreat to their own headquarters for supper, further rallies and evening serenading. It is midnight when the town finally shuts down after its memorable day in history.

October 7, 1858

Douglas Again Asserts The Supremacy Of White Men At Galesburg

Almost three weeks elapse before the fifth encounter takes place in the town of Galesburg, before another very large crowd of some 15,000 attendees. The venue chosen is on the campus of Knox College, founded in 1837 by Presbyterian minister George Washington Gale, mentor of Reverend Charles Finney, head of the Oneida Institute and early leader in the anti-slavery movement.

The weather is chilly and Douglas arrives suffering from a case of bronchitis. Between his ill health and a decidedly anti-slavery audience, he turns in a lackluster performance. His opening repeats familiar themes. The white race is supreme and it has the right to operate the country in its own interest.

This Government was made by our fathers on the white basis…made by white men for the benefit of the white men and then their posterity forever.

Lincoln and the Republicans are slandering the founding fathers with their phony interpretation of “all men created equal” and their devious efforts to abolish slavery.

The charges levelled by Turnbull and Lincoln that he favored passage of the Lecompton constitution without a fair public vote are totally contrived.

I hold to that great principle of self-government which asserts the right of every people to decide for themselves the nature and character of the domestic institutions and fundamental law under which they are to live.

Lincoln senses the anti-slavery feelings of the crowd and says that a basic sense of humanity demands that “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” be guaranteed for all men. If Douglas is successful in his goal to “nationalize slavery,” America will be made the lesser for it.

Lincoln also responds to the attack made on his patriotism at Charleston regarding his votes on the Mexican War. He confirms that he did oppose “the origin and justice of the war,” but goes on to say…

I never voted against the supplies for the army, and…whenever a dollar was asked…for the benefits of the soldiers, I gave all the votes that…Douglas did, and perhaps more.

For good measure, he says that Douglas is set on acquiring even more land to foster the spread of slavery:

A grab for the territory of poor Mexico, an invasion of the rich lands of South America, then the adjoining islands.

Most observers feel that Galesburg has been a good day for Lincoln. He again more than holds his own against the Little Giant on a public stage; advances the notion that Douglas hopes to “nationalize slavery;” and questions his basic sense of morality on the issue.

He is blowing out the moral lights around us.

Sidebar: Stephen Douglas As Slaveholder

The body of evidence supporting Douglas’ moral indifference to slavery is supported by his history as a plantation owner.

In March 1847 he nearly becomes an official slave holder when he marries Martha Martin, daughter of a North Carolina planter, who offers the couple a cotton plantation on the Pearl River in Mississippi, as a wedding present. At the time, he declines the offer, saying that, as a northerner, he lacked the knowledge to manage it properly. The rejection also seems influenced by fear of negative publicity, as he is about to make his first run for a seat in the U.S. Senate.

In 1848 his father-in-law dies and Douglas is named executor for the entire estate. In the will, Martha inherits the 2500 acre site along with some 140 slaves. The property is to remain in her name, while Douglas is to serve as manager and receive 20% of the annual income. This draws him into the operations for the first time, and he visits the land whenever political activities take him to the south. He also receives regular updates from the on-site overseer he hires, detailing crop results along with conditions of his slaves. One such excerpt goes as follows.

The negroes are in fine helth, with children increasing very fast…and they are just as fat as you ever saw hogs…The negroes will steel hogs to sell to mean white folks…Nezer is yet in the woods (and) will always give us troughable, he ran away almost for Nothing.

When he becomes a serious candidate for the presidential nomination in 1852, the subject of his connections to the Mississippi plantations comes up, and he vows to liquidate his holding and reinvest the cash back in Illinois, but he never does so. In 1853 Martha dies soon after giving birth, and ownership is transferred to Douglas’ two sons. Crop losses to Pearl River flooding finally convince him to sell the first plantation and buy another. He partners with a Baton Rouge man in 1857 and lands a 2,000 acre parcel near Greenville, Mississippi, to be worked by his 142 slaves.

The plantation continues to provide him needed revenue, especially when his personal finances become precarious in the 1850’s, and he retains control over it until typhoid fever claims him at age forty-eight on June 3, 1861.

Despite efforts to distance himself from the Mississippi plantations, political opponents cast him repeatedly as a slave-holder. He is accused of promoting the Kansas-Nebraska Bill to pump up the sales value of his slaves. His speculative purchases of land for the intercontinental railroad are said to be funded by his cotton profits. And, on the eve of the 1858 senatorial race, reports surface about mistreatment of the slaves in his care.

Douglas brushes aside all such criticism as irrelevant to his role in government.

October 13, 1858

Lincoln Again Claims The Moral High Ground At Quincy

The sixth debate in the series is held at the bustling town of Quincy, incorporated in 1840, named in honor of President John Quincy Adams, and home to many recent German immigrants. Situated on the Mississippi River, it is already a popular stopping off port for both commercial traffic and steamboat passengers.

By the time Douglas arrives at Quincy, he is near exhaustion. During the total 100 days of the campaign, records show that he makes some 130 speeches and travels 5,227 miles, by trains, boats, and carriages. Lincoln too is running from one stop to the next, logging 4,350 miles and giving 60 formal addresses in this same timeframe.

While Douglas, at age forty-nine, is recognized for his pugilistic personality and is five years younger than Lincoln, he is often prone to illnesses and is far less physically fit than “Honest Abe,” now portrayed in posters with ax in hand as the vigorous “rail-splitter.”

Unlike his teetotaler rival, Douglas is also a very heavy drinker. In fact, on October 13 he shows up at the Quincy event with a visibly “puffy face” and other signs of a hang-over from the previous night’s activities.

With the parades and other preliminaries over, Washington Square is jam packed with 12,000 attendees, many of whom have been loyal Whigs in the past and are wondering about Lincoln’s affiliation with the Republican Party.

The lead-off spot at Quincy belongs to Lincoln, and he immediately lays into Douglas for trying to divert attention away from the central issue in the contest:

The difference between the men who think slavery is a wrong and those who do not think it wrong.

There it is, plain and simple, says Lincoln.

The entire Democratic Party, including Douglas, believes that slavery is not wrong and is eager to see it take root across the nation. On the other hand, the Republicans hope to…

Prevent its growing any larger and so deal with it that there may be some promise of an end to it.

This is what the founders wanted, what the Whigs under Henry Clay wanted, and what he wants. Not the abolitionist agenda to free all the slaves immediately and turn them loose in white society. Instead, a simple prohibition to stop the spread of a moral stain and puts an “end to this slavery agitation” that threatens the Union.

A wobbly Douglas tries to respond. He begins by denying that he ever called slavery a “positive good” and agreeing that it is a misfortune for those in bondage. But, he says, the price of trying to dismantle the institution would be to tear the Union apart for good.

The rest is anti-climactic. Douglas stumbles through his usual litany, accusing Lincoln of favoring abolition and full racial equality, while continuing to assert that the morality of slavery should have no bearing when it comes to settling on the right public policy. He also says that, once free, the slaves would be unable to survive on their own.

The humane and Christian remedy he proposes for the great crime of slavery (will) extinguish the negro race.

Lincoln counters that…

His policy in regard to the institution of slavery contemplates that is shall last forever.

After an appropriate round of applause, both men head down to the landing and board the City of Louisiana steamer for the 115 mile ride south to Alton, Illinois, for their final encounter.

October 15, 1858

The Debates Conclude At Alton

The seventh and final debate follows three days later in Alton, Illinois.

Ironically it is the 1837 murder here of abolitionist editor Elijah Lovejoy that spurs Lincoln to offer his first public address, and John Brown to swear his fateful church oath to “consecrate his life to ending slavery.”

Like Quincy, Alton is another boom town, offering both a port on the Mississippi and a terminal for two railroad lines heading west and east. Like St. Louis, 22 miles due south, it intends to be a crucial commercial hub.

On an overcast day, the turn-out is disappointing, with an estimated crowd of only 5,000 people. Lincoln’s friend, the German ex-patriate, Gustave Koerner, notes that Douglas arrives again in bad shape.

His face…was bloated, and his looks were haggard and his voice almost extinct…his words came like barks, and he frothed at the mouth when he became excited.

Still he opens up with a frontal attack on Lincoln’s “house divided” speech. First, he says, because it demeans the founding fathers for lacking the wisdom to create a nation that “can no longer endure.” Second, because the predicted “all free or all slave” outcome would be accompanied by a civil war between the South and the North.

So, he wonders aloud, is Lincoln’s policy to end slavery worth the price of such a war?

He turns to Lincoln and asks if he would really deny statehood to Kansas if the people there voted in favor of slavery – and, if so, does that not signal his opposition to the sacred principle of self-government?

Next comes the false charge made by Lincoln and Senator Trumbull, who happens to be in the audience, about the Lecompton Constitution. Douglas says that he would never have allowed Kansas to be admitted as a slave state without a public vote. In fact, he says he has even had the courage to battle his own President on behalf of popular sovereignty.

He ends, as usual, by insinuating that Lincoln is an abolitionist, who believes that the “all men are created equal” line means that negroes are equivalent to white men. Instead…

The signers of the Declaration of Independence …did not mean negroes, nor the savage Indians, nor the Fejee Islanders nor any other barbarous race.

Now it is Lincoln’s turn. He has been seated toward the rear of the state, taking it all in, not even bothering this time with rebuttal notes. When he rises, he begins by poking fun at Douglas for complaining further about his own president and party.

He has now vastly improved upon the attack he made (in Quincy) upon the Administration.

Raucous laughter accompanies this observation, reinforcing Lincoln’s ability to use humor to undercut Douglas’ lecturing style as a speaker.

By now he has also heard all of the accusations before: that he wants a civil war, intends to free all of the slaves, regards blacks as equal to whites, supports inter-marriage, opposes the rights of the people to self-government. His rejoinders come with ease. He asks how many men have fled to Illinois to escape competing with slave labor and appeals to this free soil faction saying that a slave free Kansas would be an…

Outlet for free white people everywhere…in which Hans, Baptiste and Patrick and all other men from all the world, may find new homes and better their condition of life.

But it remains the immorality of human bondage that animates his defense. He quotes his mentor, Henry Clay:

If a state of nature existed and we were to lay the foundations of society, no man would be more strongly opposed than I should be to incorporating the institution of slavery among its elements.

He asks how many in the audience feel that slavery is morally right, and repeats his usual framing:

Those who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves…and under a just God, cannot long retain it.

That is the issue that will continue in this country when these poor tongues of Judge Douglas and myself shall be silent. It is the eternal struggle between these principles that here stood face to face from the beginning of time and will ever continue to struggle. The one is the common right of humanity and the other the divine right of kings.

Douglas closes with his familiar themes.

I care more for the great principle of self-government, the right of the people to rule, then I do for all the negroes in Christendom.

Then the specter of warfare should the voice of the people be drowned out by a tyrannical ban from Washington. If that happens…

The result will be bloodshed of the unholiest kind.

With that, the final debate comes to an end – some two weeks before the election of the Illinois state legislators who will have the final say in the senatorial race.