Section #3 - Foreign threats to national security end with The War Of 1812

Chapter 25: The Lewis & Clark Expedition Maps A Route To The West Coast

January 18, 1803 to May 14, 1804

Jefferson’s Search For A Northwest Passage Gets Under Way

From the moment he enters office, the visionary Jefferson is already imagining an America that stretches from ocean to ocean – with this vast territory bound together by the unifying ideals of freedom, equality and self-governance.

To begin to realize this vision, he must first focus on exploring the west. Some ten months before the Louisiana Purchase, on January 18, 1803, he gains congressional approval to spend $2,500 on a one-year expedition to complete the task. (The actual effort will take 26 months and cost $38,722.)

While he himself is a consummate easterner, his interest in mapping the west traces back at least to 1796, when he encourages colleagues at The American Philosophical Society to send expeditions across the Mississippi.

With the opportunity now his, he turns to Meriwether Lewis, to lead the effort. Lewis is only 27 years old at the time, but Jefferson has known and respected his parents in the Meriwether and Lewis families for years. He is born only ten miles from Monticello and proves to be a natural backwoodsman. He moves to Georgia for a while, mingling with the Cherokee Indians, then back to Virginia, where he graduates from Liberty Hall College before serving as a Captain in the state militia.

On April 1, 1801, Jefferson hires him as his personal secretary, at a salary of $500 a year. Lewis lives in the White House, works in the East Room, and dines regularly with the President and his top advisors over the next two years. When Jefferson asks him to head back into the wilderness, he jumps at the opportunity.

Lewis assembles a band of 33 explorers in total, including William Clark, whom he knows from his militia days, and makes his unofficial co-commander on the trip. Together they assemble their supplies for the journey, including a 55-foot keelboat, two 40-foot long canoes, food, trading trinkets and 120 gallons of whiskey.

Jefferson names them the Corps of Discovery, and lays out their goals as follows:

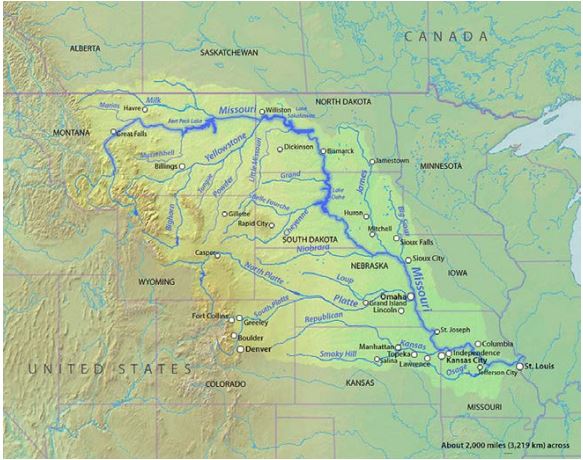

The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri River & such principal stream of it, as, by its course & communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, may offer the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce.

The hope expressed here is that the Missouri River, flowing westward from St. Louis, will actually extend all the way across the continent to the Pacific Ocean – one continuous northwest passage supporting east-west commerce as smoothly as the north-south traffic along the Mississippi.

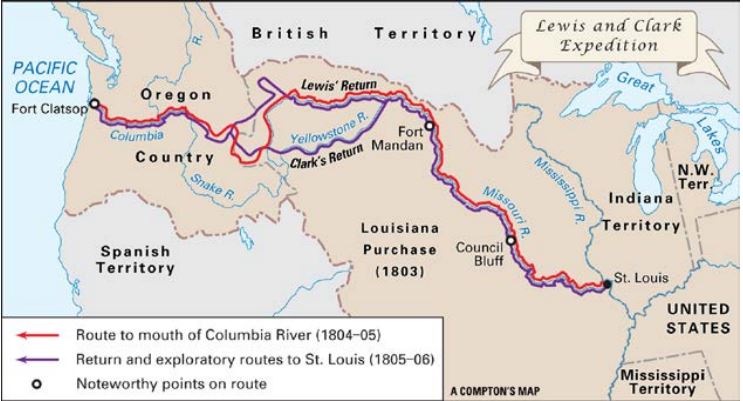

On May 14, 1804, Lewis and Clark set out from St. Louis, west along the Missouri. They will average about 10-15 miles a day, using sails and oars and, at times, even ropes, to head against the current. Lewis tends to explore the shoreline, while Clark guides the boat and handles the critical map-making duties.

May 14, 1804 – August 17, 1805

The Expedition Reaches The Headwaters Of The Missouri River

In late August, 1804, in South Dakota, they encounter their first tribe of Plains Indians, the Sioux. They also begin to spot animals not seen before in the east – antelope, mule deer, buffalo, and coyotes.

By November 1804 they have reached North Dakota, where they bold their winter camp among the Mandan tribe, and hire a guide – Touissant Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trader who is accompanied by his Shoshone wife, Sacagawea. The pair will prove invaluable as the journey unfolds, acting as interpreters and emissaries with future Indian contacts.

Before breaking camp in April 1805, Lewis ships a packet of “finds” – including elk horns, Indian corn, a magpie and a prairie dog – back east. Jefferson receives them in the late summer and plants the corn at Monticello. By then he assumes that the Corps has probably reached their destination on the west coast.

In fact, they are only half way along as they resume their voyage, further north on the Missouri, and then due west into Montana. On June 13, they encounter an amazing sight, a series of volatile rapids leading to five “great falls” over a 21 mile stretch. Lewis records the moment in his diary.

Hearing a tremendious roaring above me I continued my rout across the point of a hill a few hundred yards further and was again presented by one of the most beautifull objects in nature, a cascade of about fifty feet** perpendicular stretching at right angles across the river from side to side to the distance of at least a quarter mile.

I now thought that if a skillfulll painter had been asked to make a beautifull cascade that he would most probably have presented the precise image of this one.

As breathtaking and beautiful as these falls are, they are the first signal that the Missouri will not offer a simple unbroken route to the west coast.

The party celebrates the Fourth of July by consuming what’s left of their whiskey ration, and then totes its gear overland around the falls until July 15, when it is back in the water, drifting south toward the Rocky Mountains.

Only a month later, on August 17, their hopes for a Northwest Passage to the Pacific are over, as they discover the “end point” of the Missouri River, the headwaters at Three Forks, Montana.

August 1804- October 1805

A Rugged Journey Across The Rockies Leads On To Success

At this point they are 15 months into a journey that was supposed to take a year. Undaunted, they push on to perhaps their most formidable challenge, crossing the Rocky Mountains – the Great Continental Divide, where America’s waterways (and river currents) begin to flow advantageously west toward the Pacific. Lewis and Clark will be the first white Americans to cross this divide.

Fortunately the expedition now comes upon the Shoshones, who happen to be Sacagawea’s native tribe. They know the best routes through the mountains, and guide the way – first across the Lehmi Pass, some 7400 feet above sea level, and then along the Lolo Trail, and the rugged Bitterroot Range. Lewis regards this 200 mile slog as the most challenging of the entire trip, with all members suffering from frostbite and a lack of food.

I have been wet and as cold in every part as I ever was in my life, indeed I was at one time fearful my feet would freeze in the thin Mocki(N)sons which I wore.

After five weeks in the mountains, new canoes have been built and, on October 7, 1805, they are moving downstream on the Clearwater River. This flows into the Snake and then the Columbia River; a known landmark they had previously hoped was linked directly to the Missouri.

On October 18, 1805, they are elated to spot Mount Hood in the distance, another identified marker on their original map. Roughly a month later they have reached the Pacific Ocean, at Astoria, where they set up winter quarters known as Ft. Clatsop. Using his “dead reckoning” skills, Clark estimates they have come 4,162 miles, a figure that proves to be only 40 miles off the true mark. The elapsed time is 18 months, one way.

March 23, 1806 – September 23, 1806

The Expedition Returns Home

On March 23, 1806, the expedition begins to retrace its path back home. They are now confident enough in their knowledge to break into four separate parties to further map the Louisiana lands. They record various “incidents” along the way. Clark carves his name into a sandstone outcropping near Billings, Montana, which endures. Lewis survives the only hostile encounter with Indians, leaving two Blackfeet dead after they have tried to steal his horses and rifles. Sacagawea and Charbonneau return to their Mandan village in August. They revisit the grave of Charles Floyd, the one casualty of the trip, who died on the way out of a burst appendix.

On September 23, 1806, they are greeted as national heroes back in St. Louis. Both commanders receive land grants of 1600 acres for their efforts. Jefferson names Lewis the Governor of Louisiana, and Clark a brigadier general in the Louisiana Territory militia and Indian agent to the West.

From there the fates of the two explorers will diverge sharply. Meriwether Lewis proves ill-equipped for a life in politics. His land speculation activities go bust, his debts mount along with his alcohol intake, and he either commits suicide or is murdered by gunshot wounds in 1809, at age 35 years. Clark lives almost 30 years beyond Lewis, and becomes a successful businessman and serves seven years as Governor of Missouri. He dies in 1838 at the home of his oldest son, Meriwether Lewis Clark.

But together the exploits, and the learning, of these two explorers will fulfill Jefferson’s highest hope for the Corps of Discovery expedition.

From 1809 onward, Americans will be intrigued by the land across the Mississippi, and Jefferson’s vision of one unified nation, from sea to shining sea.