Section #4 - Early sectional conflicts over expanding slavery lead to the Missouri Compromise Of 1820

Interlude: The American Landscape In 1820

1820

The U.S. Population

The Total Population Continues To Grow At A Rapid Pace

Growing Population

In the thirty years between 1790 and 1820, America’s population has grown explosively, from 3.9 million to 9.6 million, an increase of over 10% per year, tracing to birth rates, not immigration.

Total U.S. Population (000)

| 1790 | 1800 | 1810 | 1820 |

| 3,929 | 5,237 | 7,240 | 9,638 |

| +38% | +33% | +34% |

Compared to the three global powers of Europe, the U.S. is already closing in on both Spain and its former parent, England.

European Population (MM) In 1820

| Year | France | England | Spain |

| 1820 | 30.3 | 11.9* | 11.0 |

All three “segments” of the U.S. population have expanded over the decades – whites, free blacks and the African slaves.

U.S. Population Growth By Segment

| 1790 | 1800 | 1810 | 1820 | 1820/1790 | |

| Total | 3929 | 3308 | 7240 | 9638 | +145% |

| Whites | 3172 | 4306 | 5863 | 7867 | +148 |

| Free Blacks | 59 | 108 | 186 | 233 | +295 |

Population Growth Varies Significantly By Region

A dramatic shift, however, has occurred in how Americans are distributed across the geographical landscape – and the effect is not what Southern delegates to the 1787 Convention expected.

Population Growth By Region

| 1790 | 1820 | Growth | |

| Northeast | 1,968 | 4,360 | 122% |

| Northwest | — | 793 | ++ |

| Border | 488 | 1,467 | 301 |

| Old South | 1,473 | 2,558 | 74 |

| Southwest | — | 460 | ++ |

| Total | 3929 | 9,638 | 245 |

At that time, Southerners were convinced that their region’s more favorable year-round climate for farming would cause Northerners to migrate their way – thus expanding their “share” of the total U.S. population and, in turn, their share of votes in the House of Representatives.

But this migration fails to materialize – and instead the South’s population share actually drops.

The old South – Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia – declines from 38% of the total population in 1790 to only 24% by 1820. The Border South – Delaware, Maryland, and Kentucky – is off slightly from 12% to 11%.

Meanwhile the eight Northeastern states – NH, Vt, Mass, Conn, RI, NY, NJ, Pa — remain essentially stable, at a dominant 48% share. This seems to be explained by the growing appeal of Northern cities, with more and more people being drawn to their diverse and vibrant economic opportunities, easy access to goods and services, and the allure of contemporary culture and society.

The big gains in the population shift, however, occur in the “new West” – the four new Northwest Territory states – Ohio, Indiana and Illinois – and the four Southwest states – Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama.

Distribution Of US Population

| 1790 | 1820 | Change | |

| Northeast | 50% | 45% | (5) |

| Northwest | — | 8 | 8 |

| Border | 12 | 15 | 3 |

| Old South | 38 | 27 | (11) |

| Southwest | — | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 100% | 100% |

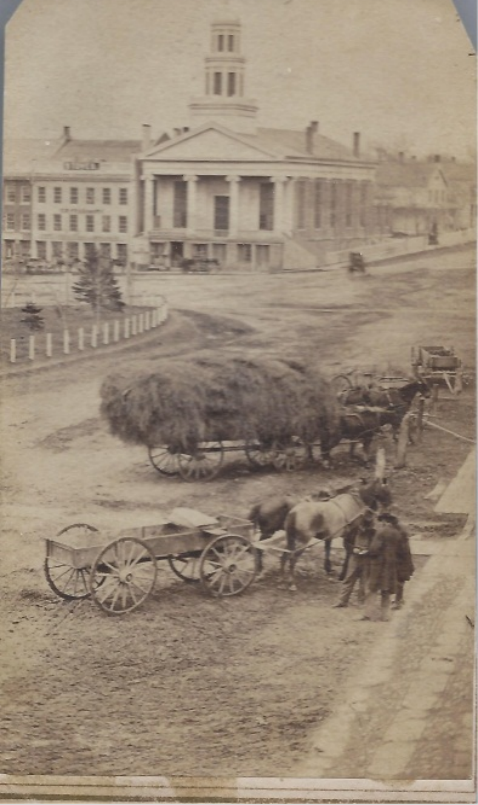

The Drive West

Settlers Continue To Move West Across The Appalachian Range

A remarkable migration west has already taken place between 1790 and 1820. It begins in Kentucky and then filters in all directions — expanding the total number of people living across the Appalachians from 386,000 to over 1.6 million, fully one sixth of the total population.

One by one pioneers have driven through mountain gaps, along primitive trails, into possible danger from native tribes, facing the uncertainties of building new log cabins, planting crops, founding towns, and starting their lives over from scratch on the frontier.

Their motivation is as old as the republic itself – the chance to realize the American Dream, to advance one’s wealth and station in life by as much as individual daring and initiative permit.

This constant drive for upward mobility is one reward of freedom, and an intrinsic part of the American character. For those moving west, the dream comes in the form of new farmland, more of it, and better, than what one had “back East.”

Ample Land Exists For Expansion

The land sought extends from the Appalachians, across the Mississippi River and into “Louisiana.” It has been “extracted,” first from Britain by warfare, then France by treaty, and finally from the Indian tribes, largely through force and deception.

By 1820 much of the land is “in the public domain,” owned by the Federal Government, and divided into “Territories,” with boundaries mostly defined by the meanderings of major rivers, and negotiations with the original thirteen states to settle disputed claims.

Terms for its sale of vary over the years — the latest established by The Land Act of 1820.

- The minimum size of a tract sold will be 80 acres (reduced from 320 in 1800);

- The price is set at $1.25 per acre (down from $1.65, before the Panic of 1819); and

- A minimum down payment of $100 is required of all buyers.

The rest is simple. Frontiersmen are told to go find the site that strikes their fancy; have a surveyor define its span; make payment to the government; write and record the deed; and the land is yours.

As always, speculators flock to acquire the new acreage, then parcel it out into smaller lots for resale and quick profits. Despite these maneuvers, data from North Carolina sales indicate that the average settler probably starts his new life with roughly the 80 acres originally intended.

Size Of Farms In North Carolina (1860)

| Acre Size | 3-9 | 10-19 | 20-49 | 50-99 | 100-499 | 500-999 | 1000 + |

| % Total | 3% | 7% | 31% | 28% | 29% | 2% | 0.5% |

The Promise Of Future Statehood Is Also A Draw

Along with the new land comes the opportunity to form new states and be admitted to the Union.

The path to statehood requires that a given Territory achieve a threshold population level of at least 60,000 residents, establish a local legislative body in some city or town, then write, vote on, and pass a state constitution, and apply to the federal government for admission.

Between 1790 and 1820, an additional eight “western” states have already joined the union – with a ninth, Missouri, about to follow suit.

Western States Admission To The Union

| # | Year | State | Slavery |

| 15 | 1792 | Kentucky | Yes |

| 16 | 1796 | Tennessee | Yes |

| 17 | 1803 | Ohio | No |

| 18 | 1812 | Louisiana | Yes |

| 19 | 1816 | Indiana | No |

| 20 | 1817 | Mississippi | Yes |

| 21 | 1818 | Illinois | No |

| 22 | 1819 | Alabama | Yes |

Changes Appear In The American Landscape

Most Americans Still Live On Farms

In 1820, the vast majority of Americans – over nine in ten – still live in the country, on farms.

Where Americans Live

| Year | Rural | Urban |

| 1820 | 93% | 7% |

They are proudly independent and self-reliant, but also “neighborly” by nature, and drawn to establishing communities, for commerce and for the common good.

Gradually their farms are connected to one another by cart paths and dirt roads, some bordered by wooden fences to contain livestock.

At the intersection of these roads, small towns form up.

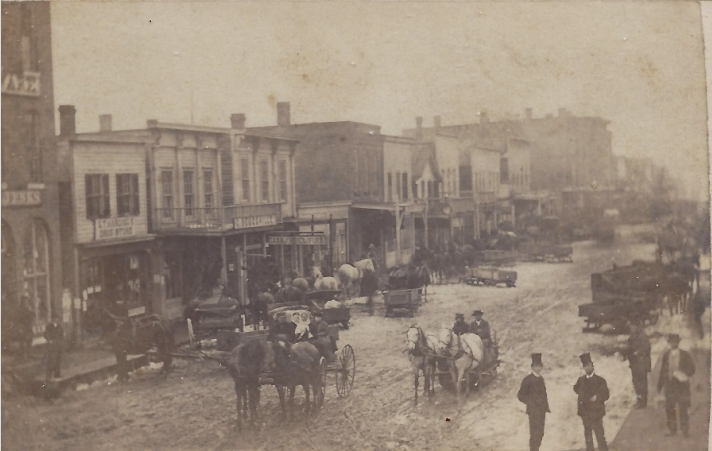

Small Towns And “Main Streets” Take Hold

The towns are typically built along a Main Street, lined on both sides by storefronts. Most are simple wooden structures, with signs announcing their wares.

The center of activity in town tends to be the General Store, a place for people to gather, to socialize, and to buy the everyday necessities of life.

Range Of Goods Sold In General Stores

| Soft Goods | Cloth bolts, silk, thread, pins and needles, buttons, underwear, hats, shoes, leather, dungarees, dresses. |

| Hard Goods | Firearms, ammunition, lanterns, lamps, rope, crockery, tableware, cooking utensils, tools, farm equipment. |

| Consumables | Coffee beans, tea, flour, sugar, spices, baking powder, crackers, molasses, tobacco, candy, select foods. |

| Apothecary | Patent medicines, remedies, soaps and toiletries. |

As towns expand, other venues open up – a saloon, an inn, a stables, possibly a jail, eventually a post office.

The Physical Infrastructure Is Upgraded

Major Roads And Turnpikes Evolve

From the beginning America’s “on-the-make” society searches for ways to rapidly transport both people and produce from here to there.

The first answer lies in roads.

Many of these originate as Indian trails, and are gradually upgraded to handle increased traffic, including the mail (or “postal letter”).

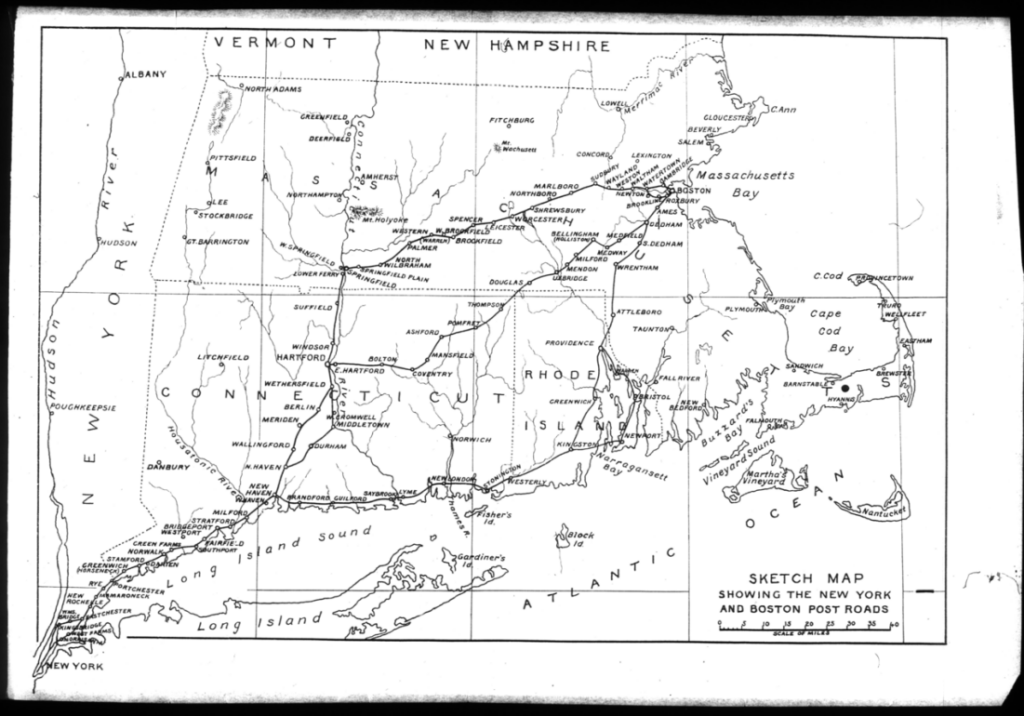

During the colonial period, most roads run roughly north and south, linking the colonies along the Atlantic coast.

The first true thoroughfare is known as the Boston Post Road, from Massachusetts through various “upper and lower” routes in Connecticut, all the way to New York City. Its name derives from the role it plays in delivering mail across the region.

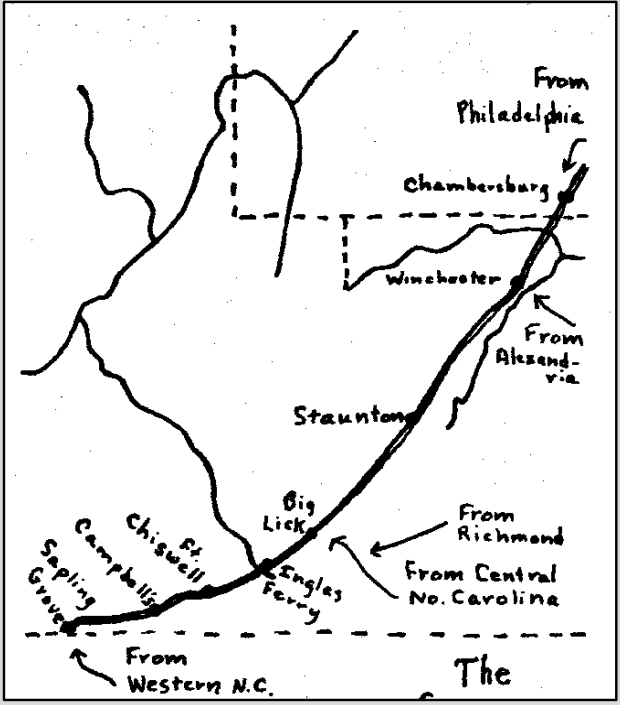

The Great Wagon Road (also known as the Valley Road) opens the way for settlers and commerce moving into the southern states. It originates at the port of Philadelphia, heads west to Chambersburg and then swoops south through the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia to the Roanoke River and into North Carolina.

Note: Map by Beverly Whitaker

Other important north-south roads include the original King’s Highway, which reaches Charleston South Carolina, and the Fall Line Road, linking Fredericksburg, Virginia and Augusta, Georgia.

Important North-South Trails And Roads In The East

| Name | Opens | From | To | Distance |

| Lower Post Road | 1678 | Boston | Greenwich, Conn. | 180 |

| Upper Post Road | 1673 | Boston | New Haven, Conn | 135 |

| Boston Post Road | 1772 | Boston | New York City | 215 |

| King’s Highway | 1650 | Boston | Charleston, SC | 975 |

| Albany Post Road | 1703 | New York City | Albany, NY | 150 |

| Great Wagon/Valley Road | 1744 | Philadelphia, Pa | Lexington, Va | 330 |

| Fall Line Road | 1735 | Fredericksburg, Va | Augusta, Ga | 500 |

Opening up new land across the Appalachian Mountain barrier hinges on development of east to west roads.

Important East-West Trails And Roads

| Name | Opens | From | To | Distance |

| Mohawk Trail | 1664 | Albany, NY | Buffalo, NY | 288 |

| Allegheny Path | 1755 | Philadelphia | Pittsburgh | 305 |

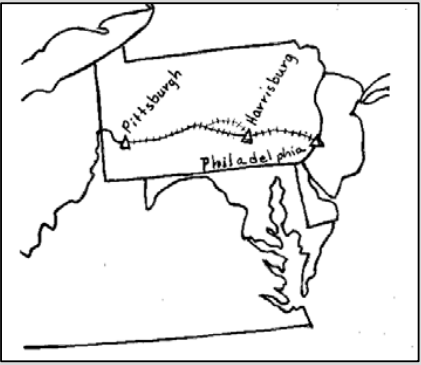

| Pennsylvania Road | 1775 | Harrisburg, Pa | Pittsburgh, Pa. | 200 |

| Braddock’s Road | 1755 | Cumberland, Md | Braddock, Pa | 95 |

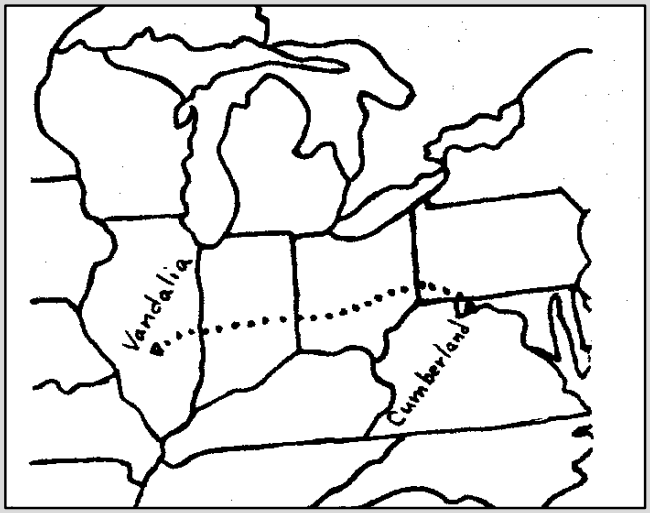

| National Road | 1811 | Cumberland, Md. | Vandalia, Illinois | 615 |

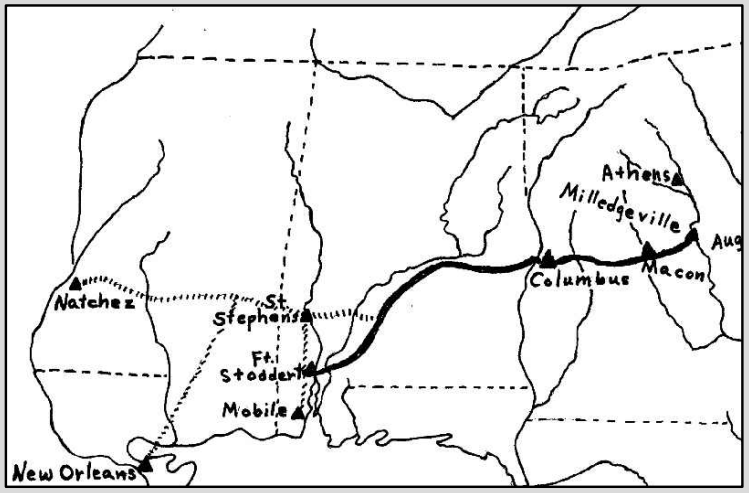

| Federal Road | 1806 | Washington, DC | New Orleans, La | 1,085 |

| Wilderness Road | 1775 | Bristol, Va. | Frankfort, Ky | 255 |

| Zane’s Trace | 1796 | Wheeling, WVa | Maysville, Ky | 230 |

The state of New York is transversed by the Mohawk Trail road, from Albany to Buffalo, on Lake Erie. Travelers move west from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh along the Allegheny Path and the Pennsylvania Road.

The most famous east-west thoroughfare of the time, the “National Road” is about half-way finished in 1820, extending west from Cumberland, Maryland – at the “gap” in the Appalachians – to Wheeling, in western Virginia. Eventually it will run some 611 miles, all the way west to Vandalia, Illinois.

The Federal Road will become another critical east-west juncture, eventually linking Washington, DC to New Orleans, over 1,000 miles to the southwest. It comprises a series of roads, dropping down from the capital through the piedmont region of Virginia and the western Carolinas to Augusta, Georgia – where it swings across Alabama and Mississippi to Louisiana.

Road Quality Is Transformed

The condition of these major roads varies widely in the 1820’s.

Most remain dirt paths, albeit smoothed and widened by decades of use.

By some, however, are already being “macadamized,” according to construction guidelines developed by the Scotsman, John MacAdam, around 1815 in England. MacAdam’s idea is a simple one that involves laying a bed of finely crushed stones over a carefully leveled dirt path, slightly bowed in the center to facilitate the run-off of rain and snow.

The use of stones enables Macadamized roads to avoid the bane of travel along dirt paths, which easily turn into mud in the presence of rain.

The benefits of these new improved stone roads are so obvious to users that some become “turnpikes” – built by entrepreneurs who line them with “toll booths” to collect fees and turn a profit.

Bridges, too, facilitate transportation, with those crossing sizable rivers often built by corporations with the intent to reap profits from user fees.

President Monroe proudly reports progress in the construction of “post roads” in his December 2, 1821 address to the Congress:

There is established by law 88,600 miles of post roads, on which the mail is now transported 85,700 miles, and contracts have been made for its transportation on all the established routes, with one or 2 exceptions. There are 5,240 post offices in the Union, and as many post masters.

The Water Ways Become Long Distance Transportation Highways

America is also able to leverage its rich abundance of water-ways to cover long distances. First with triple-masted sailing ships crammed with cargo headed toward European ports.

Then with simpler canoes, boats and barges heading up and down inland rivers.

These rivers cross-hatch the old and new states, and help bind them together around trade. Many flow for hundreds of miles, are easily navigated and cut across state lines.

Major North-South Rivers East Of The Mississippi

| Miles | States | |

| Kennebec | 170 | Maine |

| Connecticut | 419 | Connecticut, Vermont, NH, Vt |

| Hudson | 315 | New York, New Jersey |

| Susquehanna | 464 | Maryland, Pennsylvania, NY |

| Scioto | 231 | Ohio |

| Wabash | 503 | Indiana, Illinois, Ohio |

| Pee Dee | 232 | South Carolina, North Carolina |

| Savannah | 301 | South Carolina, Georgia |

| St Johns | 310 | Florida |

| Alabama | 318 | Alabama, Georgia |

| Oconee | 220 | Georgia |

Others flow east and west, and play a crucial role in opening up the new states west of the Appalachian Mountain range. The longest eastern river, the Ohio, becomes the official line of demarcation in 1787 between the “free” states of the North and the “slave” states of the South.

Major East-West Rivers East Of The Mississippi

| Miles | States | |

| Ohio | 981 | Pa, Ohio, WVa, Ky, IN, Illinois |

| Cumberland | 688 | Kentucky, Tennessee |

| Tennessee | 652 | Tennessee, Ala, Miss, Ky |

| James | 348 | Virginia |

To the north, across eastern Canada, the St. Lawrence River – Great Lakes system, runs 2,340 miles from the Atlantic coast to the tip of Lake Superior. This route will prove very important to the fur trade, which is already booming in 1820.

The St. Lawrence To Great Lakes System

| Miles | ||

| Canada | 2,340 | Atlantic Ocean To Lake Superior |

Man Made Canals Also Appear

The notion of taming the natural twists and turns and ups and downs of rivers by digging adjacent man-made canals goes back to ancient times.

By the 1770’s, however, an Englishman named James Brindley pioneers new engineering methods for canal-building that revolutionize the economics of transporting coal from mines to nearby cities.

Both George Washington and Gouvernor Morris learn of the European canals and interest grows in the colonies.

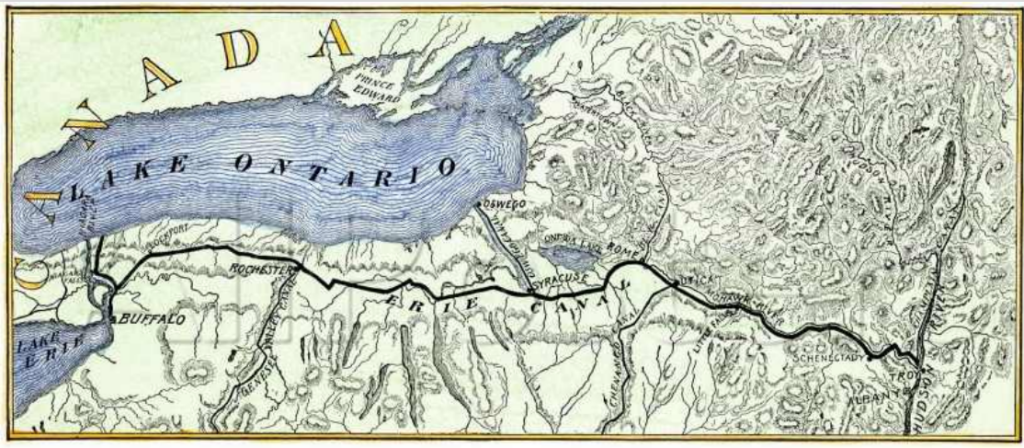

But it takes the construction of the Erie Canal in New York to capture the imagination of the public and the business entrepreneurs alike. The “grand vision” for the project involves two initiatives:

- First, “taming” the Mohawk River, which flows 149 miles east and west through the Appalachian range, between the Adirondacks to the north and the Catskills to the south.

- Then “extending” the flow another 214 miles west to the city of Buffalo on Lake Erie.

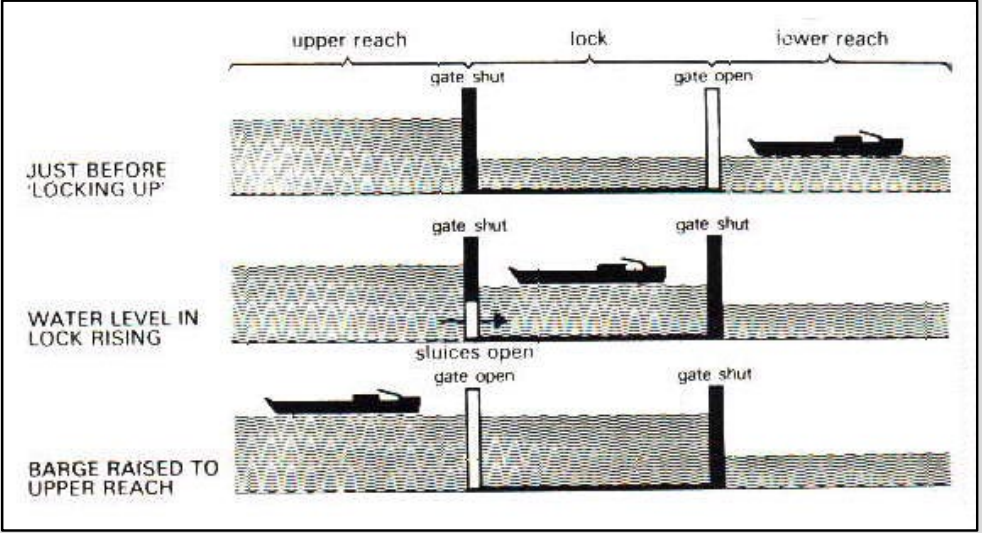

One key to canal building success lies in constructing “navigational locks” that work. Their role is to enable barges or boats to pass through sharp rises or drops in land and river elevations (e.g. “falls or rapids”) without damage. They do this by “locking” the barge in a contained tank of water, which is then flooded or drained to allow it to rise or fall to a desired height, before an exit door opens to pass it along.

When President Jefferson hears of the Erie Canal scheme in 1808 he calls it “little short of madness.”

His conclusion is prompted by the fact that land elevation drops some 600 feet between Buffalo to the west and Albany to the east. With each individual “lock” able to accommodate no more than a 12 foot change in water height, this means the canal will require construction of over 50 such individual stations – at a total cost deemed unaffordable by all who assess it.

All that is except for one Jesse Hawley, a flour merchant in Geneva, NY, who begins to calculate the cost savings the canal could deliver, especially to grain merchants in the Ohio valley. Hawley shares his estimates with Joseph Endicott, whose Holland Land Company owned land in central and western NY, and hopes the canal will boost its value.

Together these two take their plan to the powerful politician, DeWitt Clinton, who serves as Mayor of New York City between 1803 and 1815, and barely loses out to Madison in the 1812 presidential election.

Clinton sets up The Erie Canal Commission in 1810, and becomes a fierce and tireless supporter of the venture. His assessment of the project’s effects on the city will prove prescient.

The city will, in the course of time, become the granary of the world, the emporium of commerce, the seat of manufactures, the focus of great moneyed operations…and before the revolution of a century, the whole island of Manhattan, covered with inhabitants and replenished with a dense population, will constitute one vast city.

But opposition to the effort – soon labeled “Clinton’s Folly” – remains staunch. He perseveres, however, getting some 100,000 New Yorkers to sign a petition supporting the canal and securing $7 million to fund construction.

Work begins on July 4, 1817 in Rome, New York, heading east some 15 miles toward Utica. Completion of just this phase requires two years, which again raises concerns about feasibility. But the early construction lessons prove the hardest, and the building pace picks up sharply.

The canal specifications call for a breadth of 40 feet and a depth of 4 feet. Towpaths are laid out along both sides of the canal, enabling cattle or manpower to tug the barges forward.

The work is backbreaking in many ways. Trees need to be felled and their stumps pulled out; primitive bulldozer-like plows scrape the soil; clay and limestone linings form the channel; and complex aqueducts are required to steer the water. The effort continues through the intense summer heat and the frigid winters.

In the end, almost eight years and 57 locks are required to complete the project, one of the engineering marvels of the 19th century. Clinton celebrates with a ten day voyage over the canal, from Buffalo to New York City – ending with a ceremonial “wedding of the waters,” pouring a vial from Lake Erie into Manhattan harbor.

The Erie Canal immediately transforms economic prosperity throughout the state. Wheat transport on the waterway jumps from some 3500 bushels in 1820 to over a million bushels in 1830, with costs per bushel cut by 90%.

Tolls collected for use of the canal pay off the $7 million cost during that same time — and New York becomes the busiest port in America, surpassing Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore and New Orleans.

Unfortunately, DeWitt Clinton dies suddenly of heart failure in 1828 and, despite his public prominence, lacks the personal funds even to be properly buried, much less care for his surviving family. Despite this, his famous canal will be forever immortalized in American folklore and song: Low Bridge by Thomas S. Allen

I’ve got a mule, her name is Sal

Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

She’s a good old worker and a good old pal

Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

We’ve hauled some barges in our day

Filled with lumber, coal, and hay

And we know every inch of the way

From Albany to Buffalo

Chorus:

Low bridge, everybody down

Low bridge cause we’re coming to a town

And you’ll always know your neighbor

And you’ll always know your pal

If you’ve ever navigated on the Erie Canal

Infrastructure Gains Support Growing Urban Centers

While towns that are inland and “off the beaten path” tend to grow at a slow pace, full-fledged cities are appearing by 1820

Their size is determined by several factors.

One is their proximity to a sizable body of water – the east coast ocean or an inland river or lake – together with a port that accommodates shipping.

Infrastructural supports are also crucial — most notably access to one or more high traffic roads or, eventually, access to as canals and railroad tracks.

When several of these factors overlap, a city’s growth can be exponential.

In the North, for example, Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore all double or triple in population between 1790 and 1820 – and the New York count reaches 123,706, a four-fold jump.

Two Southern port cities – Charleston and New Orleans – top the 20,000 mark in total residents.

And the nation’s capital, Washington, DC, also joins the top ten list on population.

Top Ten Cities In America

| 1790 | Pop | 1820 | Pop |

| New York | 33,131 | New York | 123,706 |

| Philadelphia | 28,522 | Philadelphia | 63,802 |

| Boston | 18,320 | Baltimore | 62,738 |

| Charleston | 16,345 | Boston | 43,298 |

| Baltimore | 13,503 | New Orleans | 21,176 |

| No. Philadelphia | 9,913 | Charleston | 24,780 |

| Salem | 7,921 | No Philadelphia | 19,678 |

| Newport | 6,716 | So Philadelphia | 14,713 |

| Providence | 6,380 | Washington DC | 13,247 |

| Marblehead | 5,661 | Salem | 12,731 |

| ave | 14,641 | 39,987 |

The Overall U.S. Economy

America Forms A Viable Domestic Marketplace

The advent of towns and cities goes hand and glove with the development of a viable domestic marketplace.

At first it has simply been “the farmer’s market.”

On given days and times, families pile their surplus crops into wagons, haul them into towns, and exchange them for cash or barter.

This “exchange” symbolizes America’s free market in action:

- Sellers offering up goods or services

- To buyers with needs or wants

- In exchange for cash or barter.

“Demand” for things meets the “supply” of things, and both buyers and sellers profit from the transactions.

One man’s bushels of beans are sold for pennies used to buy a much-needed cloth shirt.

Once this demand/supply ritual takes hold in rural towns, the domestic economy booms.

Buyers and sellers; supply and demand; the engine running the U.S. economy kicks into gear.

The Macro Economy Takes Off

As of 1820, one-third of all American’s (3.1 million) are participating in the labor force.

This percent is much higher among slaves (62%) –where men, women and older children are forced workers – than among the free population (28%), where non-domestic labor is dominated by men.

Labor Force Participation (000) In 1820

| Total Population | In Labor Force | % In Labor | |

| Free | 7,830 | 2,185 | 28% |

| Slave | 1,538 | 950 | 62 |

| Total | 9,368 | 3,135 | 33% |

Despite some intermittent shocks, growth in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is robust, up from $190 million in 1790 to $700 million in 1820.

Overview Of U.S. Economy: Current Dollars (Millions)

| Total GDP | % Change | GDP Per Capita | Shocks | |

| 1790 | $190 | $48 | ||

| 1800 | 480 | 90 | ||

| 1805 | 560 | 17% | 90 | |

| 1810 | 700 | 25% | 97 | 1807 Embargo Act |

| 1815 | 920 | 31% | 110 | 1812-15 War |

| 1820 | 700 | (24) | 73 | 1819 Bank Panic |

America’s exports follow the same pattern, with rapid growth registered until Jefferson’s 1807 Embargo on trade and the dampening influences of the War of 1812 against England. But as of 1820, total exports stand at $70 million, up from $20 million in 1790.

Value Of US Exports (millions)

| Year | Total | % Ch |

| 1790 | $20MM | — |

| 1805 | 96 | ++% |

| 1810 | 67 | (30) |

| 1815 | 53 | (21) |

| 1820 | 70 | 33 |

Despite some volatility, America’s long-term economic outlook looks positive.

But The Shape Of The Economy Varies Sharply By Region

The nature of this labor differs sharply by region.

While farming and fishing remain dominant in the North, Hamilton’s vision of a diverse economy, including manufacturing, distributing and selling goods, is already materializing.

Roughly 11% of America’s total workforce are engaged in the manufacturing sector in 1820, with 70% of them located in the North.

People Working In Manufacturing Jobs In 1820

| Region | 1820 (000) | % of Total |

| North | 241.2 | 69% |

| Border | 41.1 | 12 |

| South | 64.5 | 19 |

| Total U.S. | 346.8 | 100% |

Meanwhile the Southern economy remains steadfastly committed to Jefferson’s agricultural model.

The Southern Economy

The South Bets Its Future On Agriculture

During the colonial period, plantations spring up across the South, with crops varying by terrain and weather. In the Upper South, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina, tobacco is dominant. The low country states of South Carolina and Georgia, with greater access to irrigation, turn to the generally more profitable production of rice. But the economic die is cast for all southern states in 1792 once Whitney’s seed-removal “gin” transforms the economics associated with growing and harvesting “short fiber” cotton.

From that moment on, every farmer and plantation owner in the South that can get into cotton does so.

And production soars – reaching almost 142 million pounds by 1820.

Prices for the crop vary from year to year in responses to shifts in supply and demand, with the latter affected by tariffs levied on finished cotton goods from abroad.

But in 1820, the value reaches $235 million – fully one-third of the country’s total GDP for the year!

Value Of Cotton

| Year | Cotton Lbs | Cents/Lb | Value | Index |

| 1790 | 0.1 million | $14.44 | $2 million | |

| 1805 | 59.9 | 22.59 | $135 | 100 |

| 1810 | 68.9 | 14.20 | 98 | 73 |

| 1815 | 81.9 | 25.90 | 216 | 160 |

| 1820 | 141.5 | 16.58 | 235 | 174 |

As cotton profits soar, so too does interest in opening new plantations – particularly to the west of the Appalachian range, in the newer states of Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana.

To do so, however, requires not only available land, but also available slaves.

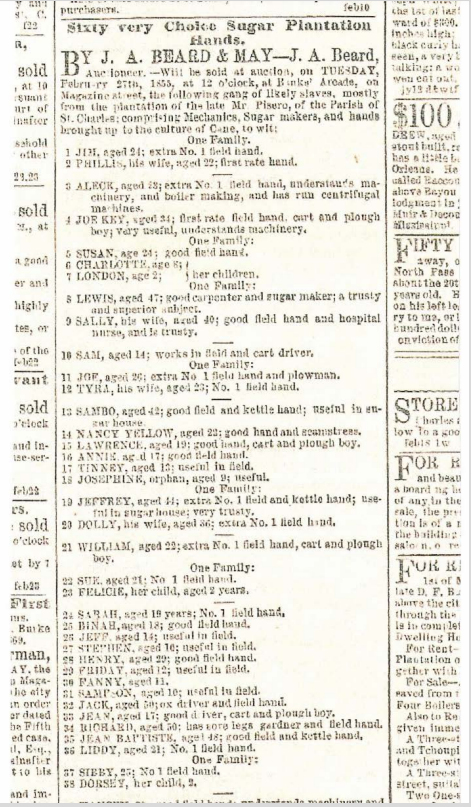

The South Also Bets On “Breeding” And Selling Slaves

By 1820 prosperity in the South rests as much on the domestic sale of slaves (“black gold”) as on sales of its raw cotton (“white gold”) to worldwide textile mills.

Since 1807 the ban on “importation” agreed to in 1787 Constitution has been in effect, and hence the only place new plantation owners in the west can get the labor they need is to buy “excess slaves” being bred on plantations in the east.

And “breeding slaves” becomes a major industry, especially in the state of Virginia.

This shocking “breeding practice” is described by ex-slave, Maggie Stenhouse, as follows:

Durin’ slave’y there was stockmen. They was weighed and tested. They didn’t let ’hem work in the field and they kept them fed up good. A man would rent the stockman and put him in a room with some young women he wanted to raise children from.

Once bred, these “excess blacks” are shipped to cities like Louisville, Kentucky and New Orleans, where daily slave auctions are advertised in newspapers and held in various locations around town.

The combination of growing demand and limited supply leads to high prices for slaves, especially for “prime field hands” and “breeding women.” In 1820 the average price for a slave has risen to $393.

This means that the total economic value of the 1.5 million slaves has reached the staggering level of $600 million, at a time when the annual value of all goods and services (GDP) is $700 million.

The “Economic Value” Of Bred Slaves

| Year | # Slaves | $/ Slave | Total $ | $/Prime |

| 1805 | 1,032M | 222 | $229 million | 504 |

| 1810 | 1,191 | 277 | 330 | 624 |

| 1815 | 1,354 | 272 | 368 | 610 |

| 1820 | 1,538 | 393 | 604 | 875 |

Shrewd plantation owners throughout the South will focus on sustaining this economic growth engine.

To do so, they will constantly support the expansion of slavery into new territory west of the Mississippi.

They will also pay careful attention to breeding excess slaves for sale in these new territories.

One such shrewd owner has been Thomas Jefferson, master of Monticello, whose Farm Book observations record concerns about his “breeding women” and their off-spring:

The loss of 5 little ones in 4 years induces me to fear that the overseers do not permit the women to devote as much time as is necessary to the care of their children; that they view their labor as the 1st object and the raising their child but as secondary.

I consider the labor of a breeding woman as no object, and a child raised every 2. years is of more profit then the crop of the best laboring man. In this, as in all other cases, providence has made our duties and our interest coincide perfectly…. With respect therefore to our women & their children I must pray you to inculcate upon the overseers that it is not their labor, but their increase which is the first consideration with us.

Jefferson’s correspondence also encourages his friends to…

Invest every (spare) farthing in land and negroes, which besides a present support bring a silent profit of from 5 to 10 per cent in this country, by the increase in their value.

A Missed Economic Opportunity For The South

The South’s near-sighted focus on agriculture finds it overlooking the economic opportunity to be had in processing cotton into thread, weaving it into whole cloth, and finishing it into the dress and household goods Americans need.

Had the South acted on this opportunity to “vertically integrate” its cotton operations – i.e. win all of the profit to be had from raw cotton, spun thread and yarn, woven cloth, and completed wares – its wealth could have increased dramatically.

While a few southern attempts are made to mimic the textile mills in New England, their success is limited. The question is “why?”

Several factors seem to explain this “missed economic opportunity” by the South:

- Planters are probably satisfied making money hand over fist simply by growing raw cotton and feel no urgent need to tackle the complexities of further processing it.

- The knowledge required to set up and run a textile mill is closely guarded at the time and requires engineering and machine-making skills that the South lacked.

- Smaller cities in the South meant that a local factory would not enjoy the benefits of a nearby, concentrated consumer marketplace for its finished goods.

- Finally, the prospect of hiring white women (like the “Lowell girls”) to work in textile factories for wages is culturally anathema in the South.

Whatever the causes, the result is that the Northern textile mills reap the profits of whole cloth and finished goods made from the South’s raw cotton – an outcome that will cause tensions and rancor between the two regions going forward in time.

The Northern Economy

Industrialization Begins To Take Hold In The North

While the southern economy is narrowly focused, the North is beginning to realize the benefits that Alexander Hamilton envisioned in capitalism and industrialization.

His ambition is to have America lead the world in “manufactures,” soon referred to as “manufacturing.”

Manufacturing is where “supply meets demand” for desired goods – especially those things that the typical farm household of the time is unable to make readily on their own. Fine clothing, furniture, glassware, carriages, firearms, timepieces, books, tools and so forth.

According to Hamilton, “manufacturing” will be driven by individual entrepreneurs who:

- Spot the emerging needs and wants of consumers;

- Design a workshop/factory to produce the desired goods;

- Secure needed capital through bank loans, stock offerings or their own cash;

- Locate the space, machines, workers, etc. to start up their operation;

- Make and deliver high quality products at affordable prices; and

- Achieve sufficient profitability to pay back investors for risking their capital.

Clearing all these hurdles will prove challenging, and many will fail.

But some entrepreneurs will persevere and succeed.

“Specialization” will be one key determinant.

Making “bolts of cloth,” for example, will require first de-constructing the overall process into discrete steps, and then optimizing methods used at each step. Critical “know-how” accrues from trial and error – the more bolts of cloth produced, the more efficient and effective the manufacturer becomes.

If high demand and profitability continue over time, opportunities to “automate” some of their processes may materialize. A new machine may be invented to spin cotton into thread or weave it into yarn that produces higher quality cloth at lower costs than was possible using hand labor.

Furthermore, they may be the only manufacturer around with enough “scale” (i.e. demand for their cloth) to be able to invest in the new machine and enjoy its cost “economies.” This endows them with competitive advantages that can become monopoly-like.

Finally, enough buyers of cloth may decide that one manufacturer consistently delivers better value for their money (high quality at fair prices) than its competitors, and become loyal to that supplier’s “brand.”

Those few companies that achieve “brand loyalty” can long endure.

Earliest Manufacturer Brands In The U.S.

| Year | Brand Name | Industry |

| 1795 | Dixon Ticonderoga | Pencils |

| 1796 | Jim Beam | Distillery |

| 1798 | Pratt Read | Tools |

| 1801 | Crane & Co. | Papermaking |

| 1802 | DuPont | Chemicals |

| 1806 | Colgate | Consumer Goods |

| 1807 | Sterling Sugars | Sugar |

| 1811 | Pfalzgraff | Ceramics |

| 1812 | Waterbury Button | Buttons |

| 1813 | Conti Group | Meat Products |

| 1815 | Loane Brothers | Tents |

| 1816 | Remington | Firearms |

| 1818 | Brooks Brothers | Clothing |

The growth of manufacturing in America is also hastened by events such as the 1807 Embargo, the War of 1812 and the Dallas Tariff of 1816, each of which limit foreign imports.

One entrepreneur who takes advantage of these events is Francis Cabot Lowell, who founds the Boston Manufacturing Company in 1814.

Francis Lowell’s Purloined Textile Mill Starts Up

Francis Lowell is born in Newburyport, Massachusetts in 1775 to wealthy and influential parents. After graduating from Harvard in 1793, he starts up a sizable business in Boston that imports textiles made in China and India and sells them from a retail storefront on the city wharf.

The interruption of his trade owing to Jefferson’s Embargo Act of 1807, sparks Lowell’s interest in manufacturing his own textiles domestically. But he initially lacks the know-how required to start up such a complicated operation.

He solves this on a two-year trip to England and Scotland, where he visits various textile mills and literally memorizes the details of their manufacturing processes – in the grand capitalist tradition of “know the world and steal the best.”

Upon his return to Boston, he transfers the blueprints he has carried home in his head to paper, sets up a corporation, The Boston Manufacturing Company, and begins the search for the cash needed to build his own factory.

He quickly raises the money by selling $1,000 shares of stock in his corporation to a string of wealthy investors who have enough faith in his venture to risk their own money to back it.

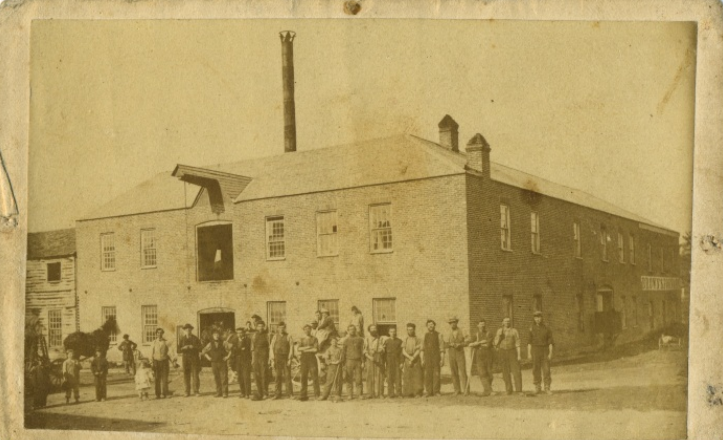

Lowell’s first mill, completed in late 1814, is located in Waltham, Massachusetts, with its spinning and weaving machines powered by water turbines driven by the currents of the Charles River. (Steam powered machines will not appear until the 1840’s.)

It becomes the first U.S. mill that completes all of the steps required to convert raw cotton into finished cloth – under one roof.

Raw cotton 🡪 cleaning 🡪 carding 🡪 spinning to thread/yarn 🡪 weaving 🡪 whole cloth

As such it delivers on all of the promises of efficient production that Hamilton foresaw, and is hugely successful from its start-up.

Unfortunately Lowell suffers from a condition known as tic douloureux, an excruciatingly painful nerve disease of the face that hastens his death in 1817, at age 42 years.

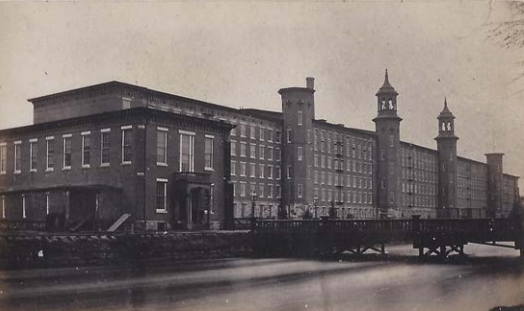

But by then a second mill is up and running, and in 1822, several more north on the Merrimack River have been built by Lowell’s corporate partners and successors. To honor him, they name their new industrial town Lowell, Massachusetts.

Northern Industrialization Fosters A New Workforce

Frank Lowell’s textile mill is symbolic of how America’s industrial economy opens up new ways to make a living, apart from agriculture. By 1820, about 1 in 5 have embraced these other options.

How People Make Their Living

| Year | Agriculture | Other Options |

| 1820 | 79% | 21% |

“Town Workies” is the name many are given, and they have traded off a strictly pastoral life on the farm for the more crowded and complex urban setting. The economic path they choose is also very different from that of Jefferson’s entirely self-sufficient farmer.

Their city jobs are wide ranging in content and pay.

At one end of the spectrum are the “unskilled workers,” such as day laborers, longshoremen and draymen, and factory workers, who live off of muscle power and are hired on or laid off at the whim of their employers. They form the lowest rung of the economic ladder, with jobs that are always threatened, especially by immigrants who may be willing to work for lower wages.

Estimated Annual Income – Unskilled Laborers

| 1790 | 1800 | 1805 | 1810 | 1815 | 1820 |

| $37 | $60 | $62 | $88 | $92 | $67 |

At the other end are “professionals,” such as doctors, engineers, lawyers, teachers and financiers – who tend to acquire unique skills through higher education, then sell this know-how on a pay-for-service basis to clients in need of their help. Because of their knowledge, people in these “white collar” jobs retain a high level of independence, often “working for themselves” as entrepreneurs. In turn both their incomes and prestige tend to be higher than all but the elite “owner classes.”

Between the “unskilled” laborers and the professionals are the emerging “urban middle class,” some working independently, others as part of a business. Some work with their hands, as “artisans” who make goods functional or decorative in nature, from clothing to furniture, household items to jewelry, tools to machinery. Others rely more on their minds, running small businesses, writing for newspapers, acting as clerks.

The breadth of jobs available varies by the size and geographic location of any given town or city. But in major cities like New York or Philadelphia, the list of occupations is quite amazing.

Non-Farming Occupations: 1820 America

| Raw Materials | Clothing/Appearance | Professionals |

| Shanties/Lumbermen | Seamstress | Clergymen |

| Miners/Sappers | Hatter | Educators |

| Trappers | Leather dresser | Doctors |

| Fishermen | Weaver | Attorneys |

| Tanner | Politicians | |

| Transportation/Goods | Tailor/Sartor | Magistrates |

| Coopers/Barrelers | Shoemaker/Cobbler | Judges |

| Rivermen | Tonsors/Barbers | Surveyor |

| Sailors | Military | |

| Teamsters | Personal Transport | Undertakers |

| Draymen | Stablers | |

| Blacksmith/Farrior | Journalists | |

| Converters | Saddler | Printers |

| Textiles | Carriagemaker | Bookbinders |

| Smelters | ||

| Ironworkers | ||

| Plowrights | Food & Drink | Financiers |

| Gunsmiths | Bakers | |

| Clowers/Nailmakers | Butchers | Entrepreneurs |

| Cutlerymakers | Packers | Ship Owners |

| Soapmaker | Brewer/Maltster | Factory Owners |

| Candlemaker | Distillers | Plantation Owners |

| Ropemakers | Other Capitalists | |

| Watchmaker | ||

| Gold/Silversmith | Merchants | Lower Skill Workers |

| Dry Goods | Factory Labor | |

| Housing | Apothecary | Clerks |

| Houseright | Haberdashers | Servants |

| Carpenter | Saloonkeeper | Longshoremen |

| Mason | Innkeeper/Ostler | Rag Pickers |

| Joiner | Peddlers | |

| Glazier | Middlemen | Tinkers |

| Cabinetmaker | Warehousers | Chimneysweeps |

| Locksmith | Factors/Brokers | Waiters |

Women Enter The Industrial Labor Force

Lowell’s textile mills also open the door for women to enter the industrial labor force.

Lowell, Massachusetts soon becomes a boom town, with over 30 textile mills being operated by some 8,000 workers. The majority of these are young women, who become known as “the Lowell girls.”

While Charles Dickens found working conditions in the Lowell factories far superior to their counterparts in London, the labor was strenuous. A typical shift for “Lowell girls” ran from 5AM to 7PM on a production line consisting of 80 workers, two male overseers, and the non-stop racket of spinning and weaving machines and air filled with cotton and cloth detritus.

“Lowell girls” work about 70 hours a week on average and are paid about 6 cents per hour or around $4 per week – a generous wage at the time.

The girls live and eat together in company boarding houses, obey a 10PM curfew, and are expected to attend church on the Sabbath and exhibit upright behavior at all times. Time off is granted for short vacations, trips to the city, exposure to various cultural events.

Despite the offer of steady work, shelter and pay, the average job tenure for a “Lowell girl” is roughly four years.

John Jacob Astor: An American Tycoon

The vast majority of men who travel east to west by 1820 are content to stake out their farm and make enough of a living to raise their family.

But a few are driven by the allure of building vast new businesses that span the continent and offer the allure of almost limitless wealth.

These men will becomes America’s first industrial age tycoons. One of them is John Jacob Astor.

John Jacob Astor is generally regarded as the fifth richest man in American history, with assets valued at $116 Billion in current dollars. He is also the very symbol of the “rags to riches” dream that has remained in the country’s culture from its inception.

Astor is born in Waldorf, Germany in 1763 and goes to work at age 14 in his father’s butcher shop. Like his brothers before him, he soon flees from home, first to London, where he learns English, and then to New York city in 1784.

On the trans-Atlantic crossing he meets a German passenger whose stories about fur-trading opportunities in America fascinate him.

In 1785 he marries one Sarah Todd, daughter of a prominent Dutch family, who brings with her a sizable $300 dowry and a keen eye for quality fur products. Together they open a shop in the city which she manages in 1786, when he goes off to Canada in search of a steady supply of beaver, otter, ermine and other pelts.

At the time, the North America fur trade resides in outposts scattered around the great salt water lake known as Hudson Bay, north of Ontario and also bordering on Quebec. These outposts are controlled by the Hudson Bay Company, chartered in 1670 by Britain’s Charles II. They trade blankets, tools and other goods to local Indian tribes for pelts, which are exported abroad and converted into felt hats, coats and blankets.

Astor ventures off into this wilderness on his own, exhibiting great physical courage, along with the business acumen needed to survive and then prosper among the native trappers and cutthroat traders. His instincts for “the right deal” are remarkable. He knows which furs will appeal to the public and how to assess supplies against prices.

As his reputation grows, he connects with leaders of another leading firm in Montreal, The North West Company, who help him become the dominant importer of pelts from eastern Canada.

He then leaps to the insight that maximum profit lies not in converting the pelts into clothing, but rather in trading them for other goods available in Europe and China. He studies international shipping, and in 1800 sends a cargo ship loaded with seal and beaver skins and other pelts to Canton in exchange for scarce supplies of silks, satins, porcelain, nutmegs and souchong teas.

The China trade makes Astor incredibly wealthy, and he spends $27,000 to buy the Rufus King mansion at 233 Broadway in NYC to house his family of six.

He founds his American Fur Company in 1808 and sets his sights next to cornering the fur trade in western Canada and the Rocky Mountains. He sends an expedition to open the Columbia River port town of Astoria, Oregon, with the intent being to ship pelts from there west to China and back east to NYC. The War of 1812 temporarily dashes his plan, but he perseveres and later dominates the western trade.

At no point does Astor relent when it comes to extending his wealth by leveraging his capital.

When Madison desperately needs funds to fight the war, he makes another killing by purchasing high yield bonds. This support, along with his political contacts in the NYC Masonic Lodge, earn him one of the five director’s slots on the Second U.S. Bank when it is formed in 1816.

He is also one step ahead of others in understanding market demand.

He sells his American Fur Company in 1834, when he senses a shift from beaver to silk hats.

The profits go into a continuing quest to buy up all available real estate on and around the island of Manhattan. He purchases Greenwich Village. He pays $25,000 to the sugar importer, James Roosevelt (great grandfather of FDR), for 120 city blocks north from 10th street to 125th and east from 5th Avenue to the East River. After the Bank Panic of 1837, be adds more plots north of the city, at bargain prices.

His strategy is to lease his properties rather than build, and by the time of his death in 1848, Astor is known as the “Landlord of New York City” and the richest man in America.

He goes down in history as the first entirely self-made tycoon in the nation’s history.

Gender Roles

America Remains A Patriarchal Society

True to its Protestant roots and its English traditions, America remains a patriarchal society in 1820.

Men are cast as the head of their households and of public affairs in general; women are expected to conform to the subservient roles they are assigned by their fathers and husbands.

Religious beliefs and practices contribute heavily to contemporary views of women – especially the Garden of Eden tale of Eve luring Adam into original sin. For the dominant Calvinist sects such as the Puritans, this forever casts doubt on the moral rectitude of all females. Eternal salvation is in the balance daily, and the prayer – “lead us not into temptation” – is often focused on women and sins of the flesh. (In 1850, author Nathaniel Hawthorne will capture these Puritan tensions in his novel, The Scarlet Letter.)

Other First Ladies

But women’s subservience at this time extends beyond religious doctrine and into the realm of law.

According to English Common Law, carried over to America, women’s legal rights are established under the principle of “coverture.”

Which means that, once a woman is married (or “covered”), she forfeits her legal rights as an independent person. Thus she is no longer allowed to own property, to sign contracts, or to participate in any business ventures. As the soon-to-be suffragette, Lucy Stone (1818-1893), will point out…

Coverture gives the custody of the wife’s person to her husband.

A host of orthodoxies regarding both men and women follow from these religious and legal precedents.

Men are expected to be in charge of their household; to work hard to support their own family’s well-being; and to participate in public affairs, from service in the militia to involvement in politics and government. In all critical decisions facing the family, their word is final.

Women too had clearly defined roles in 1820. Since their futures in society were so directly determined by marriage, girls were tutored early on to find a worthy husband. “Proper behavior” was deemed essential here, including the virtues of outward piety, modesty, appropriate dress and manners. Marriages were seldom “arranged,” and those failing to attract a husband were reduced to “spinsterhood” and probable poverty, left to live at home with their parents.

Once married, women were expected to have children, especially male heirs; to raise them properly and contribute to their education; to carry out a multitude of chores associated with maintaining a household; often to help out with farm duties; and to support and obey their husbands. While labeled “the weaker sex,” the physical demands on farm women were often extreme, doubly so since multiply pregnancies and minimal health care were commonplace.

These generalized gender roles were the norm across all regions of the country – although the stereotypes tended to be amplified across segments within the South.

Such deviations were particularly true among the elite planter class in Virginia and the Carolinas, where the culture was prone to mimicking the old world French traditions of chivalry and elegance over the more down to earth mindsets of the English Puritan “Yankees” of New England.

Fragile “Southern belles” placed on pedestals by dashing cavaliers were extant in 1820, but they were few and far between. The vast majority of females, South and North, were farm women, laboring hard from dawn to dusk to care for their homes and families.

Only A Few Women Dare To Make Their Voices Heard In 1820

Relatively few women in 1820 deviated much from their subservient roles. But some do.

They are helped along as early as 1742, by the opening of the Bethlehem Female Seminary in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Its charter argues on behalf of a revolutionary idea: “when you educate a woman, you educate an entire family.” Its curriculum covers a range of cultural and intellectual topics, spiritual exploration, vocational training and physical exercises. It encourages women’s participation in a range of fields, including education, the ministry and nursing. (It endures today as Moravian College).

Mercy Otis Warren (1728-1814) soon picks up the banner. She is a member of the prominent Otis family of Massachusetts and writes political propaganda surrounding the war with Britain. She also corresponds regularly with America’s first three presidents, publishes novels, and befriends another outspoken woman of her time, Abigail Adams.

Adams, of course, becomes the early symbol of strong and independent women, demanding to have her say in the “affairs of men.” In addition to her role as “first lady” during her husband’s presidency, she engages many of the founding fathers, especially Thomas Jefferson, on public policy. Her written admonition to her husband, John, sets the stage for things to come during the second great awakening of the 1830’s:

Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands, Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have not voice, or Representation.

Our Educational Systems

Formal Education Remains A Hit Or Miss Proposition

While education is seen as important to most Americans, little progress occurs between 1790 and 1820 in making it broadly available to all children.

Those lucky enough to be born into well off families – across regions – still benefit from personal tutors, prep schools and the higher-ed universities.

For others, formal education remains a hit or miss proposition.

The bastion of childhood education is New England, based on its staunchly Puritan heritage. It becomes the model for “grammar schools,” open to the public, albeit with optional, not mandatory, attendance. These facilities are all privately owned until 1821, when the first government run “public school” appears in Boston.

The odds of accessing formal education also go up for children clustered in towns and cities, where “one room schoolhouses” become more commonplace.

However, in 1820, the majority of America’s children still reside on farms, outside of New England, and lack the family wealth required to hire tutors or go off to school full time.

For them, and for their parents, learning is probably an aspiration, although hard to come by, and likely relegated to second place, behind farm duties and household chores.

Despite all this, the trend lines on literacy and general education are tilting upward by 1820 — with more children getting more years of formal education, on average.

This traces in part to the greater availability of teachers, as university attendance and graduation rates grow. While the vast majority of graduates are men, the teaching career is already beginning to attract women in search of options to traditional housewifery.

Literacy is also advanced by the fact that reading materials are becoming more prevalent, including children’s “readers and spellers,” which facilitate in-home schooling.

Parents too are more likely than ever to be reading, with local newspapers growing in popularity.

Newspapers Advance Literacy Along With Political Awareness

Between 1800 and 1820, the number of local newspapers in circulation more than doubles, from around 200 to over 500. They exist across all states, with New York alone offering roughly 75 different publications.

Their content includes coverage of current events, especially the political arena, public announcements, and advertising for local merchants.

But the vast majority of these newspapers survive for only a few years. Some build a reliable base of paid subscribers, but most cannot generate enough to cover their costs. Their revenue is also hurt by the fact that, once bought, papers are “passed around for free.”

The ones that do manage to survive typically supplement their income by other printing work done for businesses or state governments. To secure the latter, newspapers often align with political parties, who return the favor in the form of patronage.

Early Newspapers That Survive Over Time

| Date | Title | Location |

| 1704 | The Boston News-Letter | Boston, Mass |

| 1721 | The New England Courant | Boston, Mass |

| 1756 | The New Hampshire Gazette | New Hampshire |

| 1764 | The Hartford Courant | Hartford, Conn |

| 1785 | The Augusta Chronicle | Augusta, Georgia |

| 1785 | The Poughkeepsie Journal | Poughkeepsie, NY |

| 1786 | The Boston Chronicle | Boston, Mass |

| 1786 | Daily Hampshire Gazette | Northampton, Mass |

| 1786 | Pittsburgh Post Gazette | Pittsburgh, Pa |

| 1789 | The Berkshire Eagle | Pittsfield, Mass |

| 1792 | The Recorder | Greenfield, Mass |

| 1794 | The Rutland Herald | Rutland, Vermont |

| 1796 | Norwich Bulletin | Norwich, Conn |

| 1801 | New York Post | New York, NY |

| 1803 | The Post and Courier | Charleston, SC |