Section #3 - Foreign threats to national security end with The War Of 1812

Chapter 35: The End Of The Napoleonic Wars

Winter 1813

Joseph Napoleon Is Driven Out Of Spain

As America’s War of 1812 is playing out, the tide is turning against Napoleon in Europe.

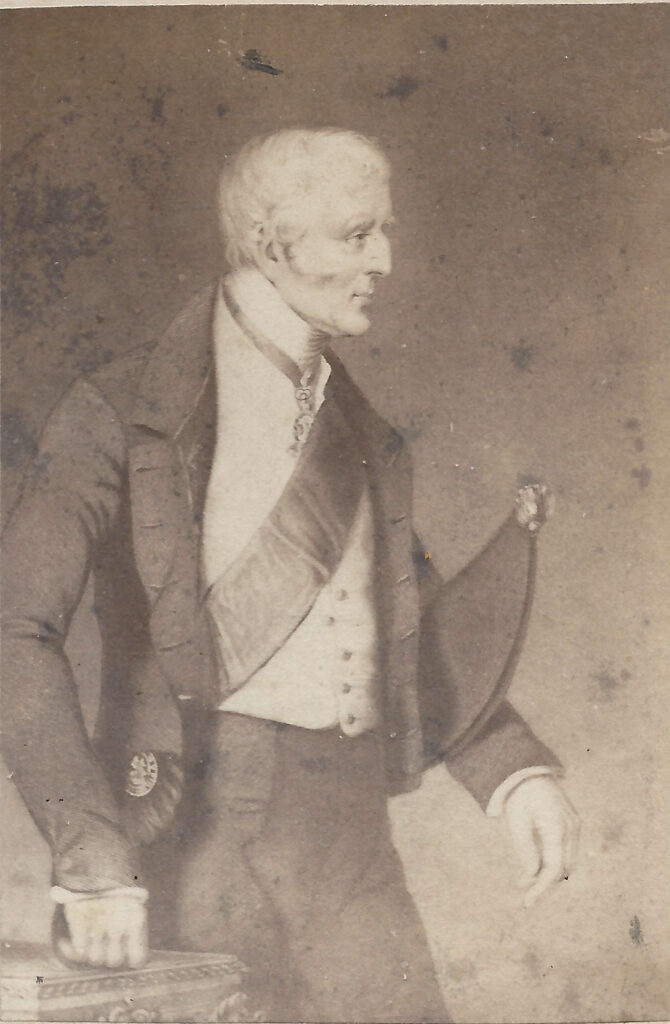

The main source of the threat is none other than the Irishman, Arthur Wellesley, destined for future fame as the Duke of Wellington. Wellesley is born into wealth in 1869, educated at Eton, and travels to France to learn horsemanship and to speak French. He wishes to pursue his love of music, but his mother pushes him into the military. He serves multiple tours of duty with the British army in Europe and India, is knighted and elected to Parliament. In 1808 he begins a six year campaign to dislodge France from Portugal and Spain.

His efforts bear fruit on July 22, 1812 – two days before Napoleon begins his ill-fated march into Russia – when his 52,000 strong coalition army (Britain, Portugal, Spain) defeats the French at the ancient city of Salamanca, 120 miles west of Madrid. The victory makes Wellesley a national hero in Britain, and lays the groundwork for a final drive against the French in Spain.

This culminates on June 21, 1813 at the Battle of Vitoria, in the northwest Basque region of the country.

While Napoleon has been plundering his army in Spain to support the invasion of Russia, General Wellesley has gathered and trained 110,000 troops (52,000 British, the rest from Portugal and Spain).

His attack at Vitoria overwhelms the much smaller French army (60,000 men) under Joseph Napoleon, and hurls them across the Pyrenees into southwestern France.

All hopes for a French resurgence in Spain disappear in October when Napoleon suffers another major setback in the east, at the Battle Of Leipzig.

After Joseph Napoleon hears of this loss, he officially abdicates the throne of Spain on December 11, 1813.

He will live on for another thirty years, first in America from 1817-32 (where he reportedly sells the crown jewels of Spain) and then back in Italy where he dies in 1868 and is buried in Les Invalides Paris, along with his younger brothers, Napoleon and Jerome.

Spring 1813

The Sixth Coalition Occupies Paris

Napoleon’s 1812 defeat in Russia emboldens the conquered nations of Europe to once again seek their liberation from France.

Prussia makes the first move here, ending its alliance on December 30, 1812, then declaring war on March 16, 1813.

In response, Napoleon assembles a large invasion force and moves east, defeating a combined Prussian and Russian army under General Peter Wittgenstein, first at Lutzen on May 2 and then at Bautzen on May 20. Both sides lose roughly 40,000 in these battles.

With the momentum on his side, Napoleon inexplicably agrees to a truce (he calls it “the greatest mistake of my life’) which commences on June 4. This gives the allies a chance to regroup – and for Austria to join the coalition, tipping the manpower edge against France.

Despite this, Napoleon almost encircles the allied army under the Austrian, Karl Furst zu Schwarzenberg, just outside Dresden, on August 26-27. The allies lose almost 40,000 men here to only 10,000 for the French, and, were it not for Napoleon’s sudden illness, the rout could have been even more devastating.

Six weeks now pass before the largest ground battle prior to World War I is fought over a four-day span, October 16-19, 1813, at the Saxon town of Leipzig.

May 1814 – March 1815

Napoleon Is Banished To Alba Before Returning

On April 14, 1814, the French minister, Talleyrand, suggests that Louis XVIII, a Bourbon, be chosen to replace Napoleon and to rule under a charter restoring pre-Revolutionary conditions. All sides agree on this option.

This leads to the Treaty of Paris, signed on May 30, 1814, restoring France’s 1792 borders and exiling Napoleon to the Isle of Alba, just off the southern coast of France, near Corsica, where he was born.

He spends 300 days on Alba before deciding to return to Paris, in response to rumors of popular uprisings against the monarchy, and fears that his country and army will be victimized by the Congress of Vienna dictates.

On March 1, 1815, he lands with 600 troops near the southern coastal town of Antibes and is back in Paris on March 19, with supporters flocking to his banner and with Louis XVIII in flight.

He quickly holds a plebiscite, showing the world that the French people back him. His next step will be to restore France to its former preeminence in Europe.

June 15, 1815

The French And Coalition Forces Arrive In Belgium

Despite Napoleon’s wishes, the Seventh Coalition countries – mainly Britain, Prussia, Austria and Russia – will have none of this. They brands him an outlaw and reassemble a huge army to oust him.

True to form when threatened, Napoleon goes on the offensive with his Armee du Nord, 130,000 strong and filled with veterans of his prior victories. He intends to take on the Coalition and attack it in detail, before it is able to concentrate the mass needed to overwhelm him.

He sets his sights on the heavily French oriented city of Brussels, 160 miles to the northeast of Paris, where he expects to encounter second tier British troops under Wellesley (soon to be Wellington) and worn out Prussians, under Blucher.

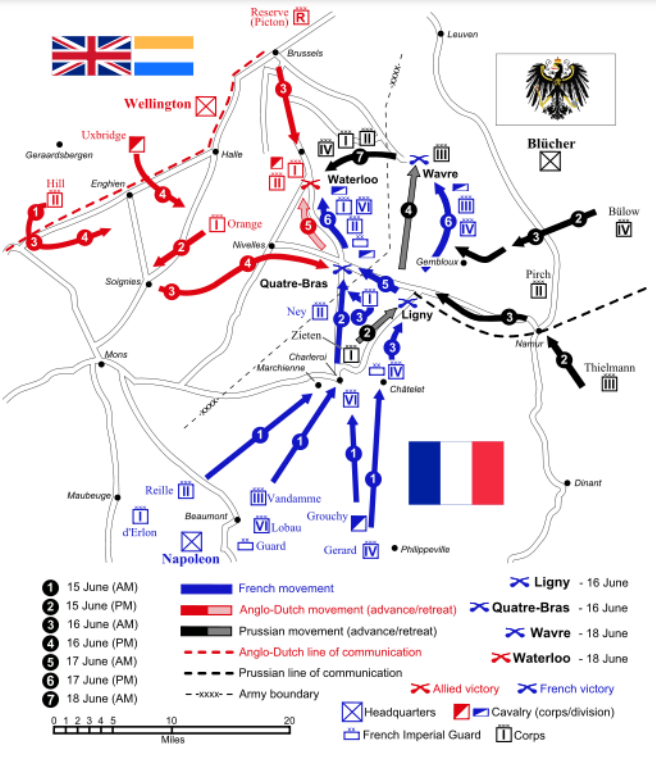

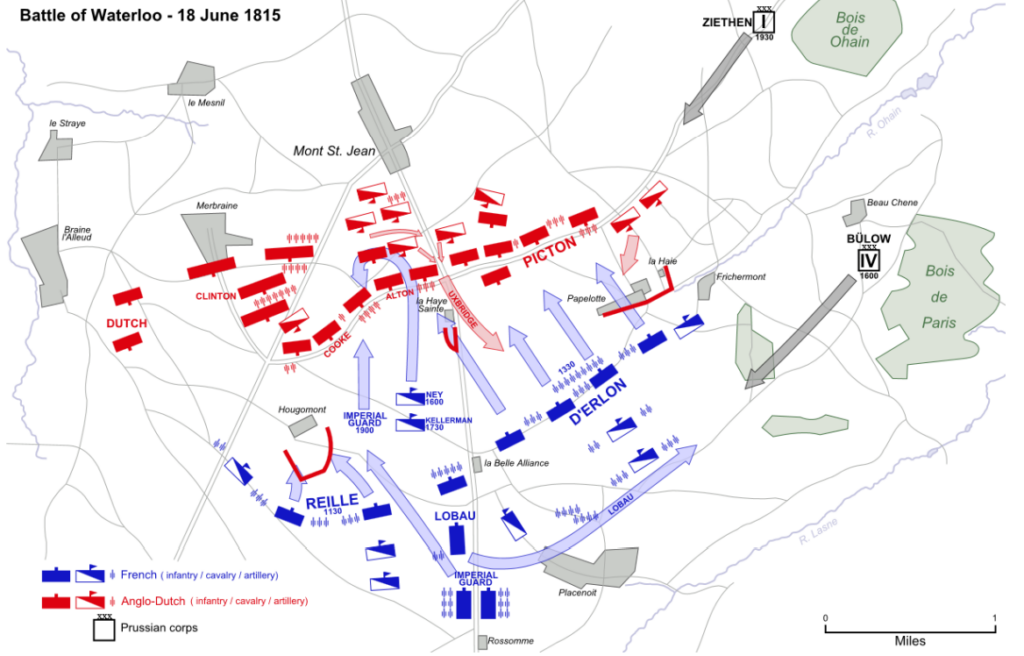

As Napoleon draws near, the allies anticipate that he will sweep north in an attempt at encirclement, but instead he dives straight between them – crossing the River Sambre on June 15 and dividing his force in two. At Quatre Bras, on his left, he places 70,000 troops under General Ney to block the English, while he moves to his right, eastward, with 60,000 me to attack Blucher’s force of 83.000 around the town of Ligny.

Ligny will be Napoleon’s final victory.

The Battle of Ligny opens at 2:30PM on June 16 and remains in the balance until Bonaparte sends in the Old Guard around 7:45 and drives the Prussians off the field to the west. During the fight, the 72-year-old Blucher leads a charge, but is knocked unconscious when his horse is shot and falls on him.

But Napoleon knows that the Prussians have only been bruised at Ligny, not routed, and he worries that they will try to reunite with the British.

He needs to attack again before that can occur.

June 18, 1815 — 2AM To 4:30PM

When Wellington hears the outcome at Ligny, he retreats from Quatre Bras, north to a high ground position he has staked out on a 2.5 mile ridge running east and west in front of the town of Mont St. Jean. A country road runs along the ridge, and intersects on the east with the main route toward Brussels, some 8 miles north.

The British General is a long-standing proponent of defensive warfare, and he deploys his forces in a way that will enable him to grind down any frontal assault on his center.

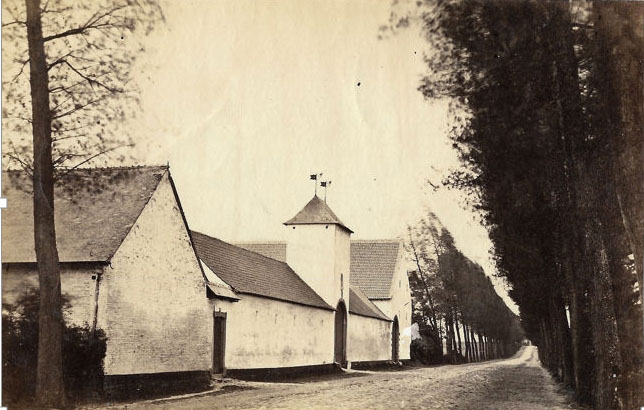

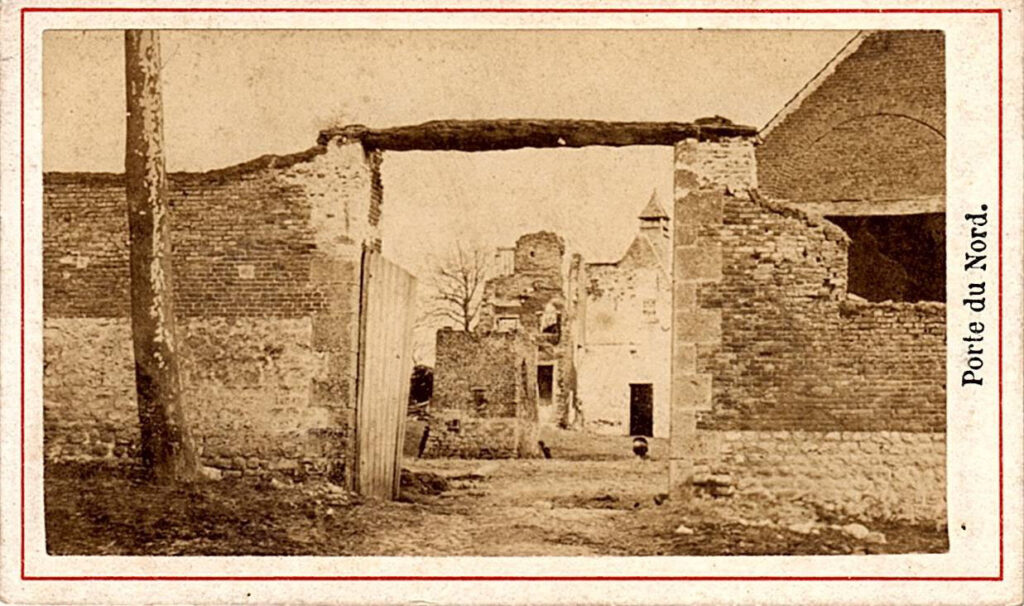

He does this by fortifying three sets of farmhouses and out-buildings., on his right flank, the Chateau Hougoumont, a half mile down from the ridge; on his near left La Haye Sainte, and on his far left Papelotte, along the road west toward the Prussians. Each site is manned and ready to send enfilading fire into all French troops trying to ascend the ridge.

Wellington has one other trick up his sleeve, and that is the ability to have his troops along the ridge lie down along the back slope while enemy artillery charges fly over their heads.

At 2 AM on the morning of June 18, the Duke, headquartered further north in Waterloo, hears that Blucher

will provide one Prussian corps to support him, if the battle occurs later in the day. This convinces him to make his stand on his current ground.

As the dawn arrives, the two sides each assemble roughly 70,000 men to do battle in a confined space of roughly 2.5 miles by 2.5 miles.

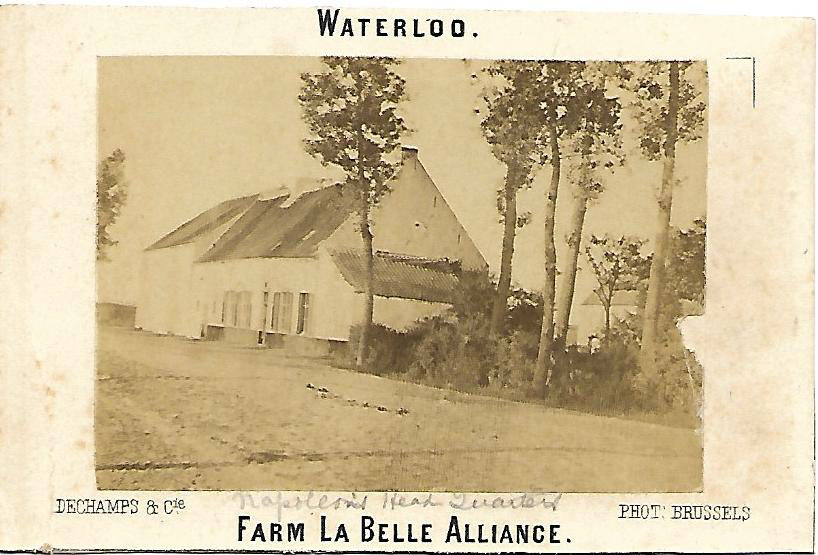

Napoleon makes his headquarters at La Belle Alliance, south of La Haye Sainte.

He rises at 8AM, takes breakfast, and rides north to review his troop alignments – his light infantry chasseurs in bright green, the light cavalry hussars, mounted cavalry dragoons and carabineers with long guns strapped to saddles, cuirassiers wearing metal breastplates, the towering grenadiers, chosen to lead assaults, in their blue and scarlet uniforms and bearskin headgear designed to add to their natural height, the cavalry lancers with their 10 foot wooden staffs tipped by a sharp steel blade, and the artillerymen, “his most beautiful daughters,” whose mastery and courage have won him many a victory.

The French Emperor is eager to conquer the British in his front and march into Brussels for his evening meal. While he has never met Wellington before, he remains typically confident. And his troops cheer and call out his name as he passes in front of them.

Meanwhile on the ridge, the Duke’s troops are lined up shoulder to shoulder according to the traditional 21 inch spacing proclaimed in the manuals. Nobody cheers his presence when he passes, because he has forbidden all such shows from within the ranks.

Napoleon is in no rush to attack. It has rained all night on the 17th, and the field of rye across which the French will make their assault is muddy and slippery. So he waits until 11:30AM, at which time he makes his first move of the day – against the crucial fortifications on his left at Hougoumont.

If Hougoumont falls, his canoners can ascend the ridge on the left, send enfilading fire down the entire British line, and claim a certain victory.

Artillery fire announces the French move, and it is quickly returned in kind: 4-12 pound solid iron balls bouncing along the ground and gouging body parts, sometimes 15-20 soldiers at a time, before being spent. Next comes the infantry, marching in order up the slope to the Chateau. The hand to hand fight there lasts for 90 minutes, the only action on the field.

When Hougoumont holds out, Napoleon next tries the British right, a heavy artillery barrage followed by massed infantry, 24 columns deep, coming up east of the Brussels road and past the fortified buildings of La Haye Sainte. Again the defenders drive the French back, led by a heroic cavalry charge behind Sir Thomas Picton, who is mortally wounded.

It is now 3PM and a pause leads many to think the battle is over. While the Duke is constantly visible along the ridge, Napoleon remains slouched in a field chair 1.5 miles back from the action, sending few orders and trusting Marshall Ney to manage the tactics. Amazingly the two do not meet face to face from 9AM until 7PM.

Around 4:00PM, Ney, evidently on his own, decides to test the British center. He does so in a highly irregular fashion, using cavalry alone, unsupported by infantry.

Wellington responds by “forming squares,” the traditional defense against cavalry. The goal here is first to discourage the horses via planted pikes, and then to shoot them – leaving their armor clad riders stumbling on the field.

And this strategy succeeds. Some 12,000 French cavalrymen ascend the slope in magnificent order, only to be broken up into mingling clusters by the square’s concentrated firepower. By some estimates they re-form on twelve occasions to charge again and be rebuffed.

By 4:30PM Wellington, stationed openly in one of the squares, tells an aide:

The battle is mine, and if the Prussians arrive soon, there will be an end to the war.

But when the French finally take La Haye Sainte, his confidence lessens – and the outcomes again hangs in the balance. Wellington has shot his bolt, his troops are fought out, and his hope for victory rests on the appearance of Blucher’s Prussians to plug his gaps.

June 18, 1815 – pm

Napoleon Loses At Waterloo And Is Deposed For Good

By 7:00PM the Emperor now knows that the Prussians, under Blucher and Bulow, are attacking his right flank, through Papelotte and, further south, at Plancenoit.

His options are running out. He has held fourteen regiments of his best troops, The Imperiale Garde, in reserve to the south. Does he use his reserves to hold off the Prussians or fling them up toward the British on the ridge? At 7:30PM he chooses the latter course.

He mounts his horse and leads five regiments of his Imperiale Garde north to the battle.

The Garde, the “Immortals,” famed for their courage – “the Garde dies, it does not retreat.”

Many expect Napoleon himself to ride at the front of his troops, but he turns them over to Ney who has already had five horses shot from under him and is near collapse. Instead of taking the Brussels road up to the ridge, Ney veers left across the same ground as his prior cavalry charge. This adds 1,000 yards to the task, with the remains of the British artillery firing away.

As the Garde reaches the apparently accessible ridge, some 1,000 British infantrymen, the 1st Foot, under the command of Major General Peregrine Maitland, rise as if from nowhere, and shoot them down. And the Garde turns and flees back down the slope.

At this moment, the French have indeed lost the battle.

Wellington waves forward his troops, just as the Prussians breakthrough from the east.

Napoleon rallies the remnants of the Imperiale Garde, south at La Belle Alliance along the Brussels road, and enables his troops to exit the field toward the south and west.

Around 9:30PM Wellington and Blucher meet up on the southern part of the field to seal their victory. The Duke has lost 15,000 killed and wounded; Blucher another 7,000.

Napoleon has lost 15,000 men – and his empire.

As the Coalition army closes again on Paris on June 24, Napoleon abdicates. He surrenders personally on July 22 to the British, seeking “hospitality and the full protection of their laws.”

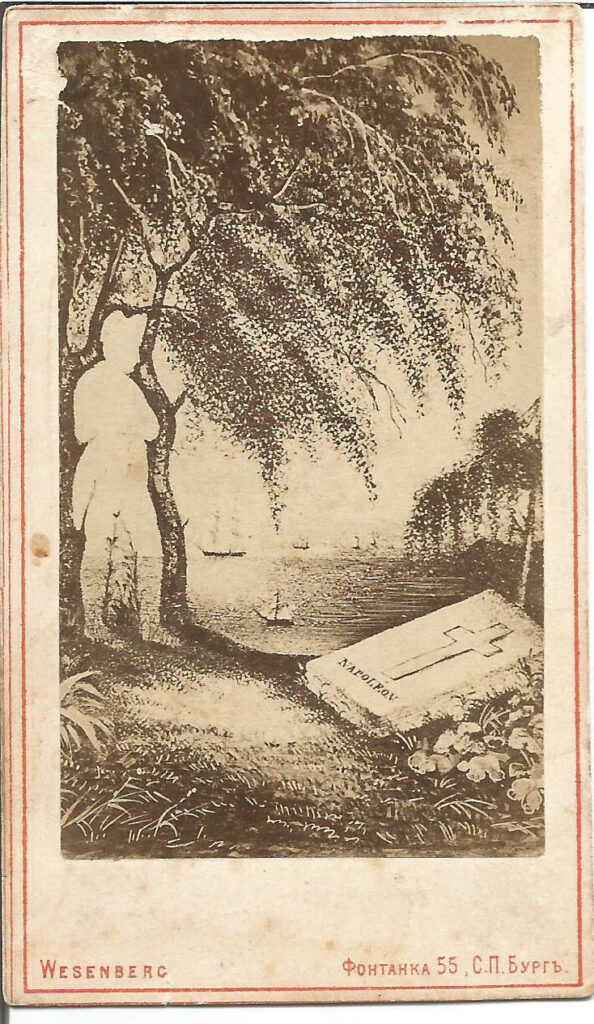

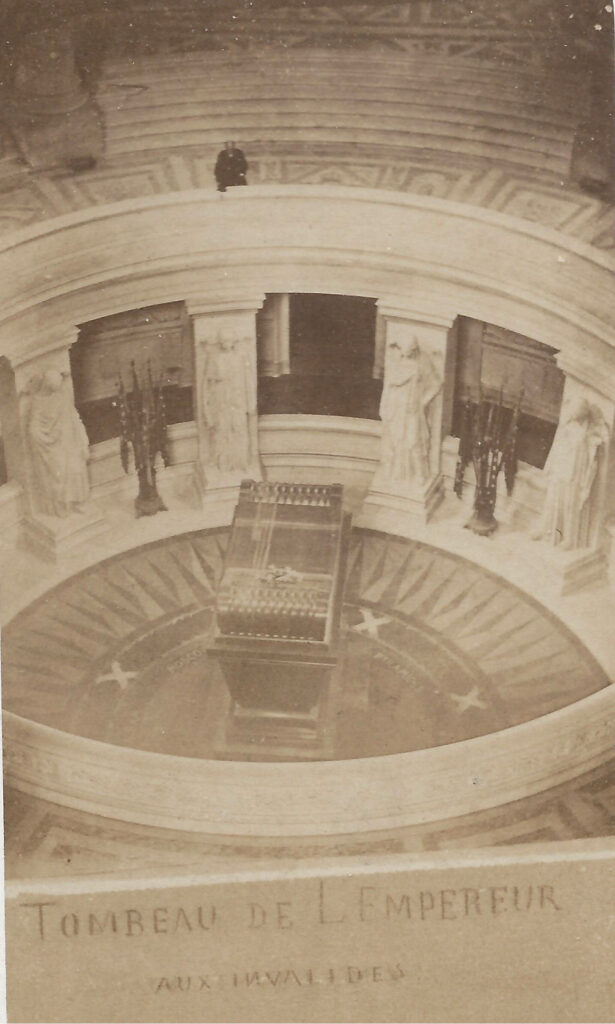

According to the traditions of the age, Napoleon again suffers banishment not execution, this time to the Island of St. Helena, one of the most isolated in the world, off southwestern Africa. He lives there until his death in 1821, presumably of stomach cancer. In 1840 his remains were shipped back to Paris, where he lies in Les Invalides.

Final photo of Nap at St. Helens – find it

Le jour de gloire has come and gone – for Napoleon and for revolutionary France.

le jour de gloire s’en est allé” — the day of glory has vanished

1814-1914

The World Reshaped After Waterloo

After the turmoil of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, the monarchs of Europe are eager to restore their authority and permanence by creating a stable balance of power between their nations.

They use the 1814 Congress of Vienna and the 1815 Paris Peace Conference to attempt to achieve these ends.

At the center of the diplomacy lies ongoing fear of France and a wish to contain any further thoughts of expansion on her part.

Within France itself, a “constitutional monarchy” is created under the Bourbon King Louis XVIII, Napoleon and his heirs are banned for life, reparations of 700 million francs are demanded and foreign troops remain on French soil until 1818.

In addition, steps are taken to surround her with more formidable border states:

- To her southwest, along the Pyrenees, the Bourbon King Ferdinand VII is returned to the throne of Spain.

- Her southeastern border with Italy is controlled by the Kingdom of Sardinia/Piedmont backed by Austria which gains control of Milan and Tuscany.

- Directly east of central France lie a jumble of states sharing both French and German roots, including what will become Switzerland, Alsace-Lorraine and Luxemburg.

- But to her northeast lie two sizable forces – the first being the new United Netherlands, with its seven provinces, including the two Hollands, under King William I of Orange.

- And then Prussia, which has traded off some of its claims to Poland to acquire a toehold along both banks of the Rhine River, in the incredibly resource-rich Ruhr Valley.

When the Prussian minister Bismarck finally patches together a united Germany in 1867, France will have found a powerful foe all along its eastern border.

What of Britain, Napoleon’s original nemesis from the time he came to power?

Their prize is absolute control of the seas with the Royal Navy and of their colonial empire stretching around the globe.

In the end, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars have shaken the monarchical pillars of Europe from Lisbon to Moscow. But, by in large, the work done in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna and The Treaty of Paris restore their crowns and deliver relative stability over the next one hundred years.

The Napoleonic Empire: Key Events 1812-1815

| 1812 | 22 July French loss at Battle of Salamanca; Wellesley hero in Spain |

| 24 July Napoleon crosses into Russia | |

| 7 Sept Borodino | |

| 19 Oct Napoleon leaves Moscow and begins retreat | |

| 14 Dec recrosses the River Nieman into France | |

| 30 Dec – Prussia withdraws from French alliance | |

| 1813 | Mar 16 Prussia declares war on France |

| April 13 France initiates campaign west | |

| May 2 Napoleon wins at Lutzen | |

| May 20-21 another victory at Bautzen | |

| June 4 Temporary armistice til Aug. 13 | |

| Allies regroup and Austria joins coalition | |

| Aug 26-27 Napoleon victory at Dresden | |

| June 21 Battle of Vittoria begins drive French out of Spain | |

| Oct 16-19 Napoleon defeated by the Allies at Leipzig in the largest battle prior to WWI | |

| Dec 11 Joseph Bonaparte abdicates throne of Spain | |

| 1814 | Feb 10-14 Five Days Campaign west of Paris– a brilliant Napoleon wins, but proves futile |

| March 30 Allies occupy Paris | |

| April 14 Louis XVIII placed on French throne | |

| May 30 Treaty of Paris ends war; Napoleon exiled to Alba | |

| 1815 | Napoleon escapes Elba and returns to France |

| “Hundred Days” March 1-June 18, 1815. | |

| 7th Coalition vs. Britain and Prussia | |

| Waterloo ends the Napoleonic Wars |