Section #21 - A North-South Split in the Democrat Party leads to a Republican Party victory in 1860

Chapter 250: The Democrat Party Fractures At Its Charleston Convention

April 23, 1860

Stephen Douglas Arrives With High Hopes And A Few Worries

The 1860 Democratic National Convention opens on April 23, 1860 at the Institute Hall, a 3,000 seat venue in Charleston which, a year later, will be memorialized as the site of South Carolina’s secession from the Union.

The opening day of the Charleston Convention coincides with Stephen Douglas’ 47th birthday, and the Little Giant arrives with high hopes of winning the presidential nomination. He has twice before been a serious contender, peaking at 102 votes in 1852, before losing to Pierce, and at 122 votes in 1856, before Buchanan wins. Now Douglas feels it is his turn. He has long been the point person in Congress for his beloved Democratic Party; his “popular sovereignty” solution remains its official position on slavery in the west; and, just eighteen months ago, he has been able to defeat the Republican, Abraham Lincoln, for his third term in the Senate.

As an astute politician, however, Douglas knows that some within the party are out to deny him the nomination. The main roots of this resistance are three-fold. First, his refusal to support Buchanan’s effort to pass the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution in December 1857 has been an embarrassment to the president and to the party as a whole. This antagonism is then compounded for Southerners by Douglas’ “Freeport Doctrine” (with popsov trumping Dred Scott) and then by his refusal to support Davis’ proposed Congressional law positively sanctioning slavery in the territories.

The extent of his opposition in the South becomes evident three days before the convention opens, when seven states — Georgia, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida and Texas – meet and agree to walk out along with South Carolina, if he is nominated. With the number of convention votes based on each state’s Electoral College allocation, the loss of these seven states would potentially cost Douglas 43 of the 303 to be cast in total.

But the Douglas camp still takes comfort in the fact that the Free States comprise 74% of that total, more than the 2/3rd needed for the nomination – even if all 80 of the Slave State votes go against him.

Distribution Of Convention Votes

| # | % | |

| Slave States | 80 | 26% |

| Free States | 223 | 74% |

| Total | 303 | 100% |

April 29, 1860

Several Southern States Bolt After A Platform Vote Goes Against Them

The convention proceeds at a crawl as various factions line up behind candidates and planks in the platform. On Day 5, the final document is almost completed as two animated speakers make their final appeals.

One is the fire-eater, William Yancey, of Alabama, who, like Edmund Ruffin, wants to see the South leave the Union unless the North buckles on its demands. The “Orator of Secession” is in rare form as he tells the audience that the argument against slavery – that it is morally evil – is all wrong, and that the practice has always been a “positive good” for the souls of the Africans and for the economy of the entire nation.

Yancey is met head-on by the equally emphatic George Pugh, Senator from Ohio. Pugh is a veteran of the Mexican War and a staunch supporter of Douglas. He has previously spoken out against the Dred Scott decision and any attempts by the South to “nationalize slavery.” Now he rises against Yancey’s efforts to force another “doughface” candidate on the delegates, like Pierce or Buchanan, who will surrender to Southern demands on behalf of party unity. As Pugh says…

Gentlemen of the South, you mistake us – you mistake us. We will not do it.

Others weigh in, including Missouri Governor Austin King who warns that the Southern plank would permanently divide the party and hand the election to Seward and the Black Republicans.

This session closes at 11:30 PM with a call for a vote the following day.

On April 28, the sixth day of the enclave, delegates are asked to choose between two alternative platform planks:

- A Southern version calling upon Congress to pass a law protecting the rights of slave owners and their “property” in the territories; and

- A Douglas-backed version throwing any decisions made by territorial governments back into the laps of the Supreme Court.

When the ballots are cast, the Douglas option wins by a fairly narrow margin of 165 to 138.

The response is a full or partial walk-out by the nine states which had sworn in advance to oppose Douglas. They leave the hall over a two day period, and simply gather in town waiting to see what happens next with the nomination of the president.

May 2, 1860

The Voting Continues But Douglas Fails To Get The Required Majority

The remaining delegates decide to proceed with trying to pick the presidential nominee.

Of the 303 total votes allocated among the various states, a total of 50 have disappeared from the hall as the first ballot is about to be recorded. According to traditional rules, aimed at indulging the South, a candidate is required to win 2/3rds of the votes to be nominated. But now the question becomes whether that should be 2/3rds of the original 303 votes, or of the remaining 253 votes after the walk-out.

Optional Voting Requirements To Win

| Base Count | Total | 2/3rd Needed |

| Before Walk-out | 303 | 202 |

| After Walk-out | 253 | 169 |

The ruling here is delivered by the Convention Chairman, Caleb Cushing, a renowned Doughface, former Attorney General under Pierce, a supporter of Buchanan, and no friend of Stephen Douglas. He demands that the threshold be unchanged from the original plan, meaning that 202 votes (2/3rds of 303) are required to win.

While Cushing’s ruling dramatically lengthens the odds for Douglas, the fact is that the slavery plank he favors only receives 165 of the 303 votes cast. Clearly, there is more Northern resistance to him than anticipated, most likely from those embarrassed by his refusal to support the Lecompton Constitution..

The competition for Douglas comes primarily from two candidates from slave states that have remained in the hall.

Virginia puts forward Senator Robert M.T. Hunter, a 51 year old planter with a very distinguished career in government service, including a stint as Speaker of the House (1839-41), three terms in the Senate, and an offer from Millard Fillmore to become Secretary of State, which he declined. He is pro-slavery, but not a fire-eater, instead committed to searching for compromises to preserve the Union.

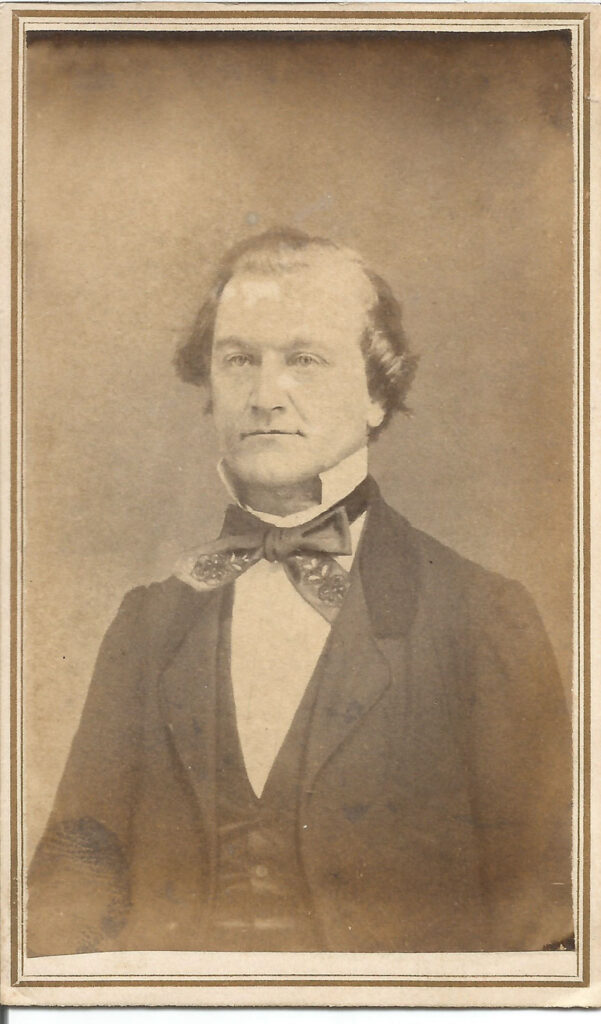

The other contender is 67 year old James Guthrie, from Kentucky, best known as an astute businessman for his prominent role in developing the city of Louisville. Franklin Pierce recognizes his financial talents and names him Secretary of the Treasury in 1853. He is the leading force in the Cabinet, a “hard money” man, who uses the windfall revenue from California gold to pay down the federal debt. After leaving office in 1857 he eventually becomes president of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. Like Hunter, Guthrie is a slave holder, but also a staunch opponent of secession.

The first nominating ballot, cast on April 30, sets the tone for all that follows. Douglas collects 146 votes, well short of the 202 mark required, while Hunter and Guthrie split about 80 of the remainder. From there another 56 ballots are taken through May 1, with Douglas never exceeding 152 and Guthrie pulling ahead of Hunter, but peaking at only 66 votes.

Voting For Democratic Party Presidential Nomination:

| 1st | 2nd | 13th | 25th | 30th | 37th | 47th | 57th | |

| Stephen Douglas – Illinois | 146 | 147 | 150 | 152 | 152 | 152 | 152 | 152 |

| Robert M.T. Hunter – Virginia | 42 | 42 | 28 | 35 | 25 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| James Guthrie – Kentucky | 36 | 36 | 40 | 42 | 45 | 64 | 66 | 66 |

| Andrew Johnson _ Tennessee | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Joseph Lane – Oregon | 6 | 6 | 20 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| Daniel Dickinson – NY | 7 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| Jefferson Davis – Miss. | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Others | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2/3rds needed to win | 202 |

What Douglas now sees is the extent of the opposition he faces not only in the South, but also the North. Then another piece of bad news materializes. It comes from his long-term ally in the House, and convention manager, William Richardson of Illinois, who reports that the New York delegation will abandon him on the 60th ballot, if he hasn’t won by then.

The only option for Douglas at this point is retreat, and the stalemated convention declares a recess on May 2, after ten days of turmoil. The new plan calls for the convention to resume in Baltimore on June 18, roughly a month after the Republicans are scheduled to meet, on May 16 in Chicago.

Meanwhile, the Southern walk-outs decide to hold their own convention on June 11 in Richmond.