Section #1 - America’s years as a British Colony end with The Revolutionary War

Chapter 6: The Declaration Of Independence

1763–66

Britain Begins “Taxation Without Representation”

Meanwhile, in Britain, the 25-year-old King George III and Charles Townshend, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, turn their attention to conditions in their American colonies.

What they find is that while Britain has triumphed in the field during the French & Indian Wars (1754–63), the battle for North America has been financially costly for the crown. To help pay off the debts, the king decides to extract more revenue from the colonists in a series of heavy-handed acts that cumulatively end the harmony that existed between Britain and the colonies, and leaves the Americans feeling bullied and angered, then outright rebellious.

The initial indignity is the Proclamation of 1763, which demands that any colonial families who have settled west of the Appalachians abandon their homes and return east. Presumably so the crown can sell back this land, won in the war, for a profit.

The Sugar Act of 1764 adds taxes on sugar, coffee, and wine, while prohibiting imports of rum and French spirits.

Another 1764 command, the Currency Act, prohibits the colonies from issuing its own paper money, a move that tightens British control over all economic transactions in the colonies.

In March 1765, the crown further ups the drive for revenue with the Stamp Act, which requires that a paid-for seal be affixed to all printed material—from legal documents and licenses to everyday items like newspapers, pamphlets, almanacs, and even playing cards. Attempts to justify this move center on the “need to defend the colonies from future invaders.”

Colonial resistance to the Stamp Act is immediate and widespread, especially among the more influential segments of the population: land owners, merchants, ship-builders, lawyers, and printers. Britain has imposed another tax absent any input or debate from the elected burgesses with their local councils and governors. Where will this end? And, besides, which enemies are left? And hasn’t the performance of the local troops during the recent war demonstrated that the colonists are now capable of defending themselves?

Resistance from abroad shocks the English. For show, Parliament passes the Declaratory Act, stating that the crown has the absolute right to impose whatever demands it deems appropriate on its colonies. But then it repeals the Stamp Act in 1766, a first “flinch” that signals at least a token American victory.

For the moment, both sides back off from the building tension.

December 16, 1773

The Boston Tea Party Signals Open Resistance

The period of calm, however, is brief.

In 1767, Townshend imposes a series of taxes on staples such as lead, paint, glass, paper, and tea.

Organized resistance materializes around Boston. Members of a “revolutionary body” known as the “Sons of Liberty” vow to oppose collection of the new duties by boycotting the imports. Shortages are offset by increases in local production and smuggling.

In 1768, Britain responds with a show of force by sending troops into Boston to ensure tax collection, and handing the bill for housing them to the colonists through the Quartering Act.

The result is a growing sense of betrayal among the colonists. Only five years earlier, they fought and died on behalf of the king in the war against France. In return comes the imposition of onerous taxes and armed enforcers.

Almost inevitably, anger turns into violence. On March 5, 1770, a mob of protesters at the custom house begin pelting British guards with stones. The redcoats fire into the crowd, killing five civilians and wounding seven. One victim, some say the first, is Crispus Attucks, a “mixed race mulatto,” who is either a freedman or a run-away slave at the time of his death.

This event is christened “the Boston Massacre” and word of it spreads rapidly across the colonies.

Again, the British back off with Prime Minister Lord Frederick North rescinding the Townshend taxes on everything but tea.

This stand-off lasts until 1773 when a new Tea Act imposes restrictions on free trade— demanding that all sales of the commodity be funneled through British agents of the East India Company rather than local merchants.

Reaction comes quickly. On December 16, 1773, a Sons of Liberty band, poorly disguised as Mohawk Indians, climbs aboard British ships in the Boston Harbor and dumps 342 crates of tea into the water.

Britain reacts quickly to this “Boston Tea Party.”

A series of punitive measures known as the “Coercive or Intolerable Acts” are mandated. The most severe measure closes the port of Boston, which effectively shuts down the economy in the city and threatens to starve the population. The order is to remain in place until the locals pay 15,000 pounds to cover the cost of the lost tea.

September 5, 1774

The First Continental Congress Convenes

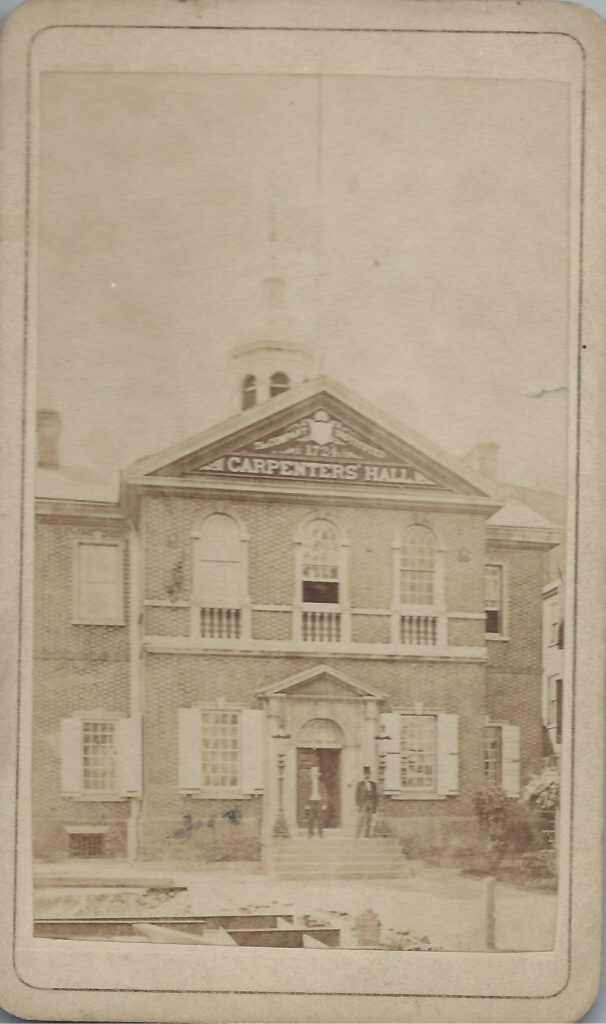

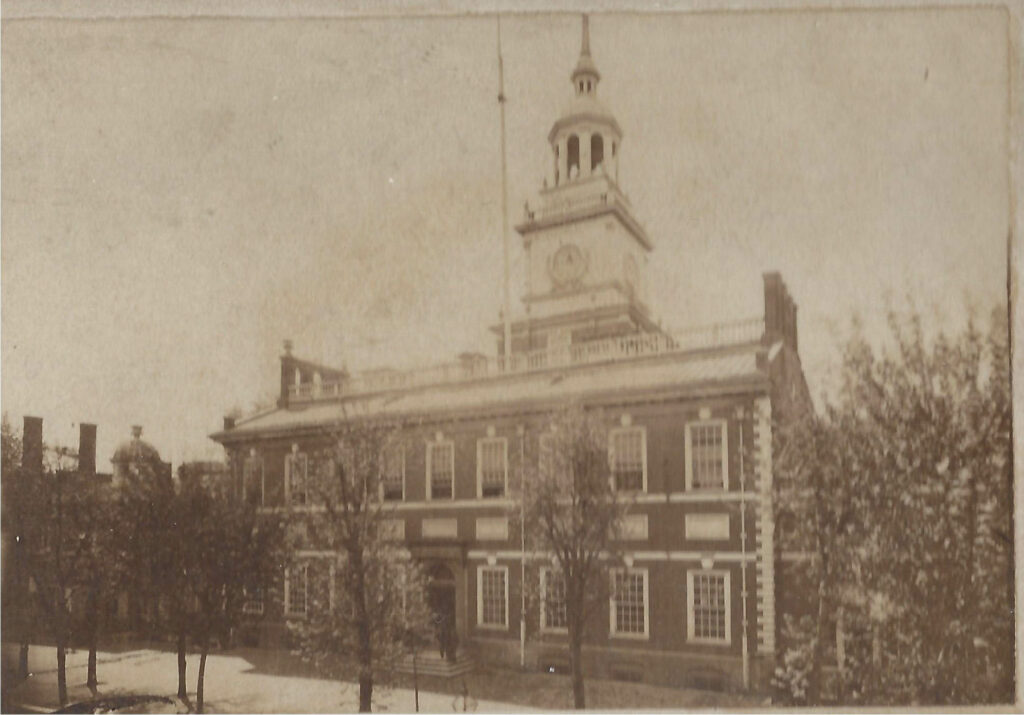

scene of the First Continental

Congress

These “Intolerable Acts” further inflame colonial passions.

Sons of Liberty chapters begin to spread beyond New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania, eventually reaching into all thirteen colonies. Meetings are held at “Liberty Trees” in town centers or local taverns, often led by local merchants like Sam Adams and John Hancock, those hit hardest by new taxes.

Newspapers and broadsides capture the growing antagonism toward Britain.

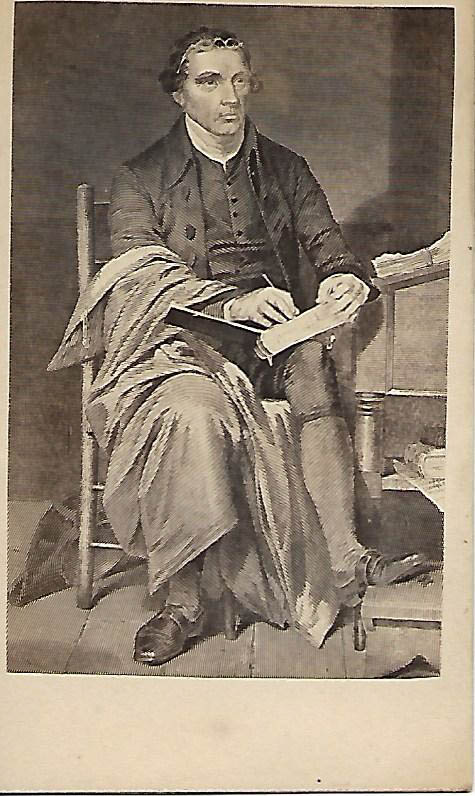

In July 1774, Thomas Jefferson, a 34-year-old Virginia planter and burgess, publishes a pamphlet, A Summary View of the Rights of British America, laying his grievances against the men have the right to govern themselves.

This is quickly followed by a First Continental Congress—a watershed moment for the colonists, and a precursor to the formation of a future independent national government.

It is held at the two-story Carpenters’ Hall guild house in Philadelphia over a seven-week period beginning on September 5, 1774. Twelve of the thirteen colonies are present, with only Georgia missing.

Peyton Randolph, speaker of the House of Burgesses in Virginia, presides over the Congress, which comprises a total of 56 delegates, all elected by their local legislatures to speak for their colony’s interest. Among those present are many of the men who will shape America’s future.

Some Delegates at the First Continental Congress

| Representing | Total # | Some Members |

| New York | 9 | John Jay Robert Livingston |

| Pennsylvania | 8 | Thomas Mifflin Joseph Galloway Thomas McKean Robert Morris |

| Virginia | 7 | George Washington Peyton Randolph Richard Henry Lee Patrick Henry |

| South Carolina | 5 | John Rutledge Christopher Gadsden |

| Maryland | 5 | Matthew Tilghman |

| New Jersey | 5 | William Livingston |

| Massachusetts | 4 | John Adams Samuel Adams |

| Connecticut | 3 | Roger Sherman |

| Delaware | 3 | George Read |

| North Carolina | 3 | Richard Caswell |

| Rhode Island | 2 | Stephen Hopkins |

| New Hampshire | 2 | John Sullivan |

The central debate occurs between those like the Virginian, Patrick Henry, who favor a clean break with England, and opponents, such Joseph Galloway, a Loyalist from Pennsylvania, who will ultimately join the British army.

In the end, the majority agree to send a sharp message to the crown by imposing a boycott on all British imports to begin on December 1, 1774. This will not only reduce revenue flowing to Britain, but also signal the growing capacity of the colonies to manufacture the finished goods on their own.

On the question of actual independence, the Congress decides to take a wait-and-see stance for the moment, and then reconvene a second Congress on May 10, 1775 to revisit conditions at that time.

The Americans now look to Boston to see what happens next.

April 19, 1775

The Shot Heard Round the World

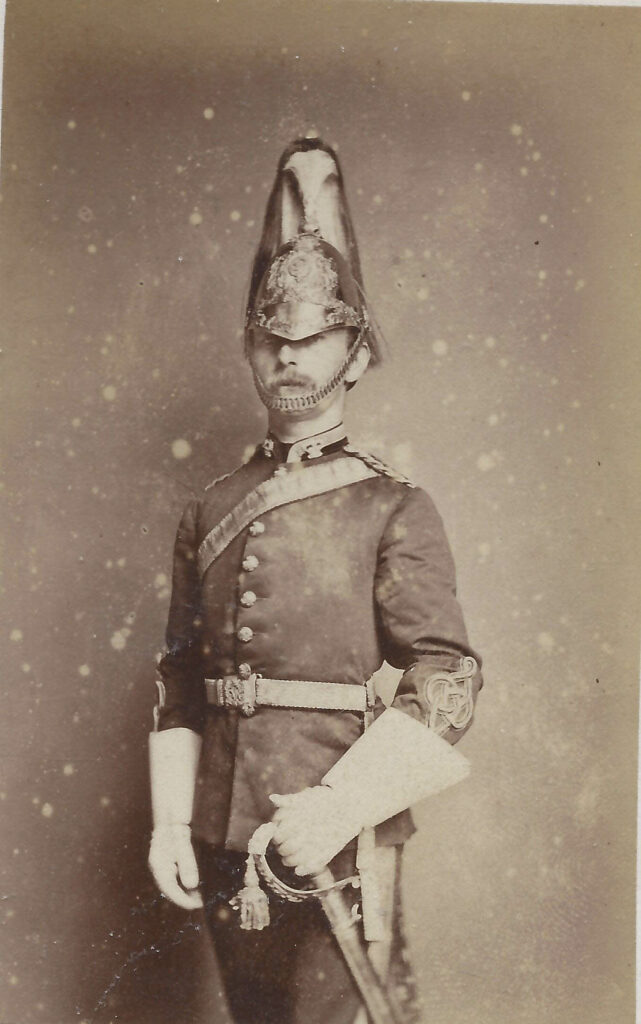

A new figure is now on the scene in Boston, Major General Thomas Gage—named on May 13, 1774, Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay—ready to impose martial law if need be.

Gage has been in America for almost twenty years, arriving to fight in the French & Indian Wars, rising to become commander in chief of all British forces, settling down with his family in New York City. He misses the Boston Tea Party while on leave in England, and returns with orders to quell the rebellion.

Over the next year, Gage tries to harness what he regards as the potentially dangerous impulse toward “democracy.” Rather than resort directly to force, he makes several attempts to stabilize the situation by forming local councils to resolve conflicts. But these fail, and he becomes increasingly concerned about rumors that the Sons of Liberty are threatening violence against the crown.

Indeed, talk of open rebellion is now sweeping across the colonies.

Four weeks later, the inflammatory rhetoric turns into bloodshed.

On April 14, 1775, Gage orders his troops to march sixteen miles west to the town of Concord, arrest two rabble-rousers, John Hancock and Samuel Adams, and seize all weapons that might be used against the crown. Around 10 p.m. on the night of April 18, some 700 Infantry Regulars under Lt. Colonel Francis Smith depart Boston to carry out Gage’s directive.

However, their plan to take the Americans by surprise is foiled by one Paul Revere, a Boston silversmith who doubles as an intelligence agent for the “Committee on Public Safety.” Revere learns of the planned British route—by boat across to the Charleston peninsula—and signals advance warning by having two lanterns (“one if by land and two if by sea”) hung in the bell tower of the Old North Episcopal Church. He then completes a midnight ride across the countryside to Lexington, awakening the minuteman militias along the way, before meeting up with Adams and Hancock to plan a defense.

Upon hearing Revere’s news, they decide to make a stand against the British troops when they arrive.

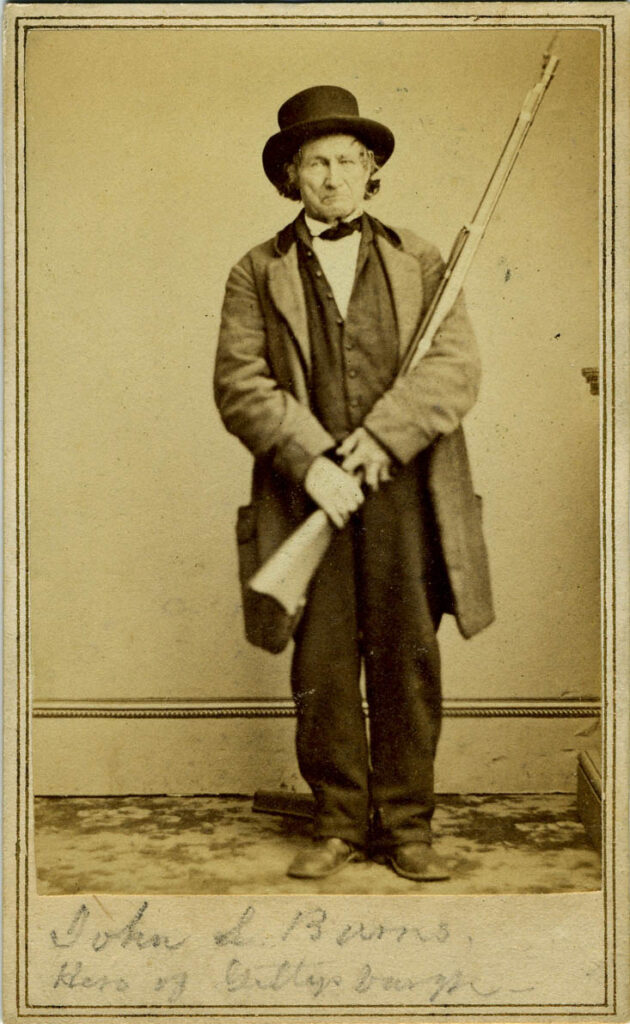

The American forces gather at the village of Lexington, roughly ten miles west of Boston on the road to Concord. There, around 5 a.m., some 80 colonists exchange fire with British Regulars. After suffering eight men killed and ten others wounded, they are driven away.

The redcoats reassemble and march another six miles to the town square in Concord, which the local militia has abandoned in favor of higher ground to the west. When a unit of roughly 90 British Regulars cross over the Concord River at the North Bridge, they are attacked and overwhelmed by 400 militiamen storming down from the hills.

The colonists have won their first organized battle with the mighty British army!

By the rude bridge that arched the flood

Concord Hymn (1837)

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled

Here once the embattled farmers stood

And fired the shot heard round the world.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

The shocked and alarmed Lt. Colonel Smith decides to retreat from Concord around noon—but his movement is vexed by continuous harassment from the colonists, whose forces reach over 2,000 strong as the day wears on.

All that saves the redcoats is a rescue contingent of 1,000 men under Earl Percy that meets them around 2:30 p.m. in Lexington and opens cannon fire to momentarily stem the militia attacks. Still, the skirmishing continues back to Boston with the infuriated redcoats ransacking homes and stores along the way as retribution for their losses.

By nightfall, they are securely entrenched within the city, despite the remarkable assembly of some 15,000 armed militiamen who surround it by daybreak.

The battles at Lexington and Concord are no more than minor skirmishes when it comes to real warfare.

But April 19 casts yet another die against any hope for reconciliation with Britain.

May 2, 1775

Americans Seize the Governor’s Palace in Virginia

The Colony of Virginia rivals Massachusetts as a center of discontent.

Since 1771, the Governor of the “Province” has been the Right Honorable John Murray, a Scotsman whose formal title is Lord Dunmore.

Dunmore’s approach to governing Virginia lies in ignoring the local council, the House of Burgesses, and acting on his own agenda, which focuses on warfare against the Shawnee Tribe for control over inland territory. His efforts deplete the Virginia militia and the financial coffers.

When Dunmore turns to the burgesses in 1773 for more men and money, it responds with a list of complaints about increased taxes in general and his administrative abuses in particular. After that, Dunmore dissolves the House of Burgesses in 1774.

This infuriates the Virginians, especially Patrick Henry, already known as the “Son of Thunder” for his fiery oratory. On March 23, 1775, Henry’s speech to the Virginia Convention, a de facto House backup, ends with this stirring plea:

Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?

Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!

Like General Gage in Boston, Dunmore also chooses to deprive rebel access to military supplies in April 1775. His focus is on gunpowder stored in the armory at Williamsburg. On April 20, he orders a small band of Royal Navy marines to transfer the gunpowder to their ship docked on James River. But when the fifteen barrels arrive, they are met by a contingent of local militia ordering they be returned, as property of the colony and not the king.

The stand-off boils over shortly. The rebels threaten to storm the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg. Dunmore announces his intent to impose martial law, free all slaves held by the rebels, and “reduce the city to ashes.” As word of the April 19 battle at Concord spreads, more Virginia militiamen appear, eager to drive Dunmore and the British out of Williamsburg.

Two prominent Virginians, Peyton Randolph and George Washington, lobby for a peaceful resolution. But, on May 2, the 150-man Hanover County Militia, serving under Patrick Henry, march on the capital. They drive Dunmore and his family out of the palace and extract a £330 payment for the gunpowder from a wealthy Loyalist in town. This temporarily ends the conflict. Henry attends the Continental Congress and Dunmore boards the HMS Fowey, from which he will direct future attacks against the rebels before returning to England in 1776.

May 10, 1775

The Second Continental Congress Convenes

As the conflict mounts, the colonists must now figure out what to do next.

On May 10, 1775, they convene the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia at the Pennsylvania State House, subsequently known as Independence Hall.

While many delegates are holdovers from the prior meeting eight months earlier, some important new faces include John Hancock from Massachusetts, who succeeds an ailing Peyton Randolph as President of the Congress.

Ben Franklin, the 69-year-old writer, inventor, publisher, and political operative from Pennsylvania joins them, as does the youthful Thomas Jefferson of the Virginia House of Burgesses.

The Loyalists in the chamber muster enough support to block the “radical faction,” who continue to call for an immediate declaration of independence from Britain.

Still, after the April 19 bloodshed at Concord and the surrounding of Boston by angry militiamen, all delegates recognize the importance of united decisions and actions.

The first priority is national defense, in case violence intensifies. The delegates agree to form the Continental Army, funded by domestic and foreign borrowing, with each state expected to contribute a fair share of money, men, and materials.

The Loyalists balance the military initiatives with what becomes known as the “Olive Branch Petition,” written by the intensely principled Quaker pacifist, John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, whose 1768 plea calls for a unified front among the colonists:

Then join hand in hand, brave Americans all! By uniting we stand, by dividing we fall.

The petition criticizes Parliament (not King George) for onerous taxing policies, but expresses hope for a peaceful resolution with America remaining in the British Empire. This will be one of many back and forth entreaties on both sides of the dispute over time, none of them healing the breach.

Once this Second Congress opens, it will function continuously until March 1, 1781, an almost six-year period that sees 343 delegates cycling in and out of the meetings and thirteen different men serving as president.

Despite the lack of formal legal authority to govern, the Second Continental Congress will muddle its way to the policies and procedures that determine the destiny of the fragile new nation.

May 10, 1775

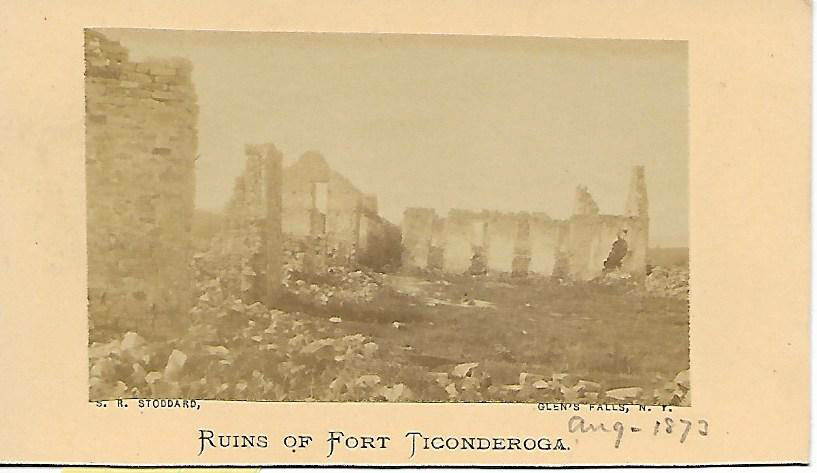

The Green Mountain Boys Capture Ft. Ticonderoga

On the same day the Second Continental Congress convenes to map out a unified strategy, an independent band of New Hampshire militiamen known as the “Green Mountain Boys” capture Ft. Ticonderoga, at the southern tip of Lake Champlain, some 300 miles northwest of Boston.

The raid is led by two firebrands, Ethan Allen, leader of the Boys, and Benedict Arnold of Massachusetts, who joins the initiative at the last second.

The main goal is to prevent the British from using Ticonderoga as a staging area to mount an attack from behind against the American militiamen surrounding Boston. They also hope to capture the fort’s weapons, and to encourage Canada to ally with the colonies in rebellion against the crown.

A force of 200 raiders approach the fort at daybreak on May 10, ready for action. The outcome, however, is comical rather than heroic.

Ft. Ticonderoga, so pivotal in the French & Indian Wars, has been left essentially unprotected by the British.

The raiders finally corral a sentry who announces the American’s presence to the fort’s commander who, in turn, surrenders his sword.

Unlike Concord, the rebels never fire a single shot to record their victory, one with strategic importance.

The colonists now control a critical stepping stone into Canada and the long-range French cannon and mortars they will use later on.

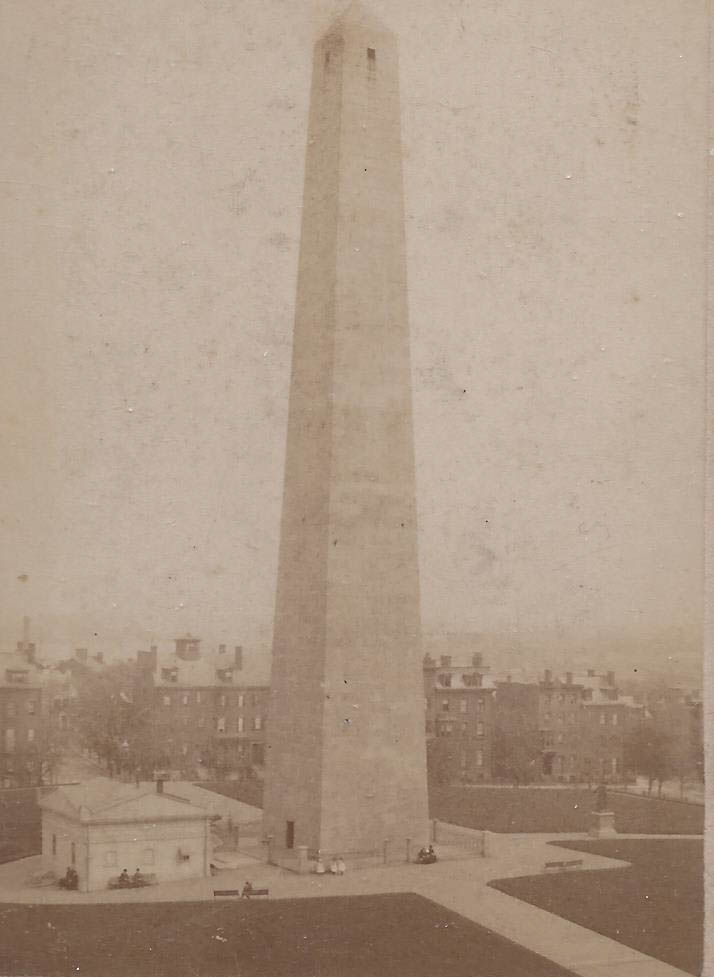

The Battle of Bunker Hill

Back in Boston, the battered redcoats have retreated from Concord to their city enclave where General Gage is tardily plotting his strategy. He has 6,500 troops at the moment, and a Royal Navy which controls sea lanes that almost totally envelop Boston. He faces more than twice that number of militiamen arrayed across the various land approaches to the city from the east and south.

When word of the Concord defeat reaches England, King George III ships off three top field generals to support, then replace Gage: the conspicuously courageous, but sometimes tardy Lord William Howe; Howe’s second in command and personal adversary, Henry Clinton, who grew up in New York City; and finally, “Gentleman John” Burgoyne, aristocrat, playwright, rake, and military man, ambitious for glory.

On June 14, the Continental Congress counters by naming George Washington Commander in Chief of the Continental Army. They give Washington 2 million continental dollars to fund an army, and order him to consult closely with Congress on all major operations. The new commander has served in the British army for seven years, demonstrating remarkable courage and leadership during the French & Indian Wars before resigning in 1759 at age twenty-seven. His life since then has been that of an English aristocrat, running a vast plantation in Virginia and mastering politics as a local burgess.

His Continental Army is a motley crew, short on weapons, gunpowder, training, even uniforms—with its officers distinguished by colored ribbons pinned to their vests—pink for brigadiers, purple for major generals, and blue for the commander in chief. In the beginning they enlist simply to “stand up for their basic rights as Englishmen.” But soon enough, in response to the king’s declaration that they are “traitors,” they swing to the “Glorious Cause of America” and independence from the crown.

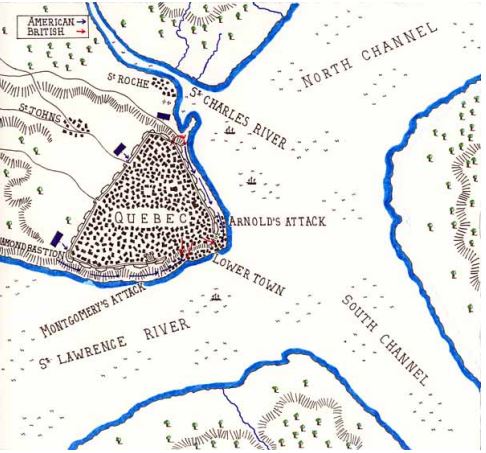

Washington arrives with two initiatives in mind: drive the British out of Boston by siege and out of Canada by striking at Quebec City. The key to the siege will lie in controlling the high ground encircling the city—Bunker and Breed’s Hills to the north on the Charleston peninsula and the Dorchester Heights east of the “Boston neck.”

On June 17, 1775, Washington moves in the north at the Battle of Bunker Hill that ends with the British controlling the field, but at a cost of over 1,000 casualties. Henceforth there will be no doubt in Howe’s mind about the determination of the rebels.

August 23, 1775

George III Vows to Quash the Rebellion

The initial American move into Canada and the siege of Boston provoke a sharp response from Britain.

On August 23, 1775, King George declares that an “open and avowed” rebellion is under way in America and refuses to receive the so-called “Olive Branch Petition” offered by the Second Continental Congress.

In early October, Admiral Samuel Graves, overall commander of the British fleet in North America, orders Lt. Henry Mowat to conduct reprisal raids on colonial seaports associated with the rebellion.

Mowat assembles a five-ship fleet, heads out of Boston Harbor, and drops anchor about 115 miles up the coast at Falmouth Harbor. On October 18, he informs the townspeople that he intends to mete out punishment for their defiance of the crown, to commence in two hours. When the locals refuse to pledge allegiance to the king, Mowat begins an eight-hour bombardment of the now abandoned city, followed by a landing party of marines instructed to burn everything left standing. In the end some 400 buildings and homes are destroyed.

The king then takes another signal step against the colonists on October 27, 1775 in a hardline speech delivered to the opening of Parliament. He states that the rebels have broken their vows of allegiance to the crown—in effect calling them traitors—and that he intends to use his own forces, as well as foreign alliances, to suppress the conspirators.

So much hope of some for an “Olive Branch” solution.

December 30, 1775

Americans Retreat After Defeat at Quebec City

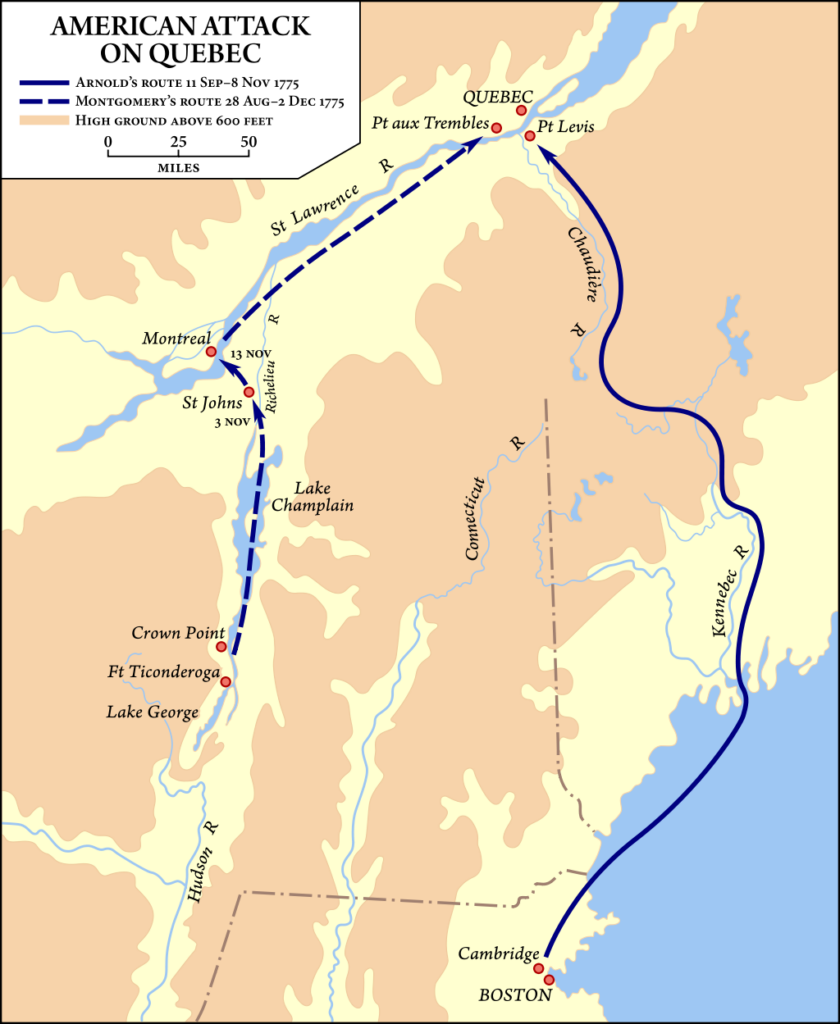

Soon after the June 1775 battle at Bunker Hill, Washington decides to go on the offensive and invade Canada.

The prize is the British citadel at Quebec City, scene of their famous victory over the French in 1759. The additional hope, which will prove futile, being that once the fighting begins the British settlers in Canada will join the rebel cause.

Overall command of the invasion is given to Major General Philip Schuyler, a member of the Second Continental Congress from New York, who previously fought for England in the French & Indian Wars.

Field command falls to General Richard Montgomery, who moves northeast up the St. Lawrence River, taking Ft. Ticonderoga on May 10, 1775 and Montreal on November 14.

He is joined there by a precocious nineteen-year-old, Aaron Burr, who interrupts his study of law to engage in frontline combat against Britain over the next four years. Montgomery immediately promotes Burr to the rank of captain, and selects him as his aide-de-camp.

On December 2, these two join up below Quebec with Benedict Arnold, who has slogged his way overland from the southeast. Between them, they have 900 men to throw against the 1,000 British troops under Major General Guy Carleton, recently appointed to defend the stronghold.

On the snowy night of December 30, 1775, the Americans begin to move against Quebec City, with Arnold’s 600 men advancing on the right toward the Palace Gate and Montgomery’s 300 men coming up on the left, across the Plains of Abraham.

But the American assault fails. Arnold is shot in the ankle and turns command over to Brigadier Daniel Morgan. Montgomery is killed by the first English volley, and Burr, along with his disheartened troops, turns back. By dawn on New Year’s Eve, Carleton retains control of the city, with casualties of only eighteen men against 60 killed or wounded Americans and 426 others captured.

A lackluster siege of the city follows, but the American momentum has run its course—and the British soon begin their roll-back of America’s incursion into Canada.

Naval control around Quebec brings Carleton reinforcements—7,000 Regulars and 3,000 German mercenaries—bringing his muster up to 11,000 men. Over the next ten months he throws them against an expanded force of 6,000 retreating Americans under Schuyler and General Horatio Gates, who succeeds the dead Montgomery.

Back come the rebels, exiting Montreal in June 1776, with even the belligerent Arnold voicing his dismay.

The junction (with) Canada is now at an end. Let us quit (here) and secure our own country before it is too late.

But the English chase him, sailing another 75 miles down Lake Champlain to a victory on October 11, at Valcour Island, over a ramshackle “fleet” of mostly flat-bottomed, single-masted, three-gun boats scrounged up by Arnold.

Both sides now pause for the winter, with Carleton back north at St. John’s Island and Schuyler, Gates, and Arnold returning south to their final stronghold at Ft. Ticonderoga.

March 17, 1776

The British Are Forced Out of Boston

After the Battle of Bunker Hill, a nine-month period of essential stalemate sets in around Boston. Washington lacks the long-range cannon needed to threaten Gage’s troops in the city—while Gage is able to resupply his force from British ships entering the harbor unmolested.

Washington’s focus now shifts south, to Dorchester Heights, which threatens both the city itself and the shipping lanes. But to succeed, Washington needs artillery with two-mile range, and obtaining them will require a minor miracle.

The miracle is performed by 25-year-old Colonel Henry Knox.

His feat lies in transporting 54 heavyweight mortars and cannon from the captured Ft. Ticonderoga 300 miles down Lake George and overland across the Berkshire Mountains to Boston. The task is one of brute force, made doubly difficult by severe snow, ice, and bitter cold. On January 27, after a seven-week trek, Knox and his guns reach Boston.

Once they arrive, Washington throws all his resources into constructing a surprise redoubt and battery on Dorchester Heights. His engineers work secretly and silently throughout the night of March 4. When the British in Boston wake the next day, they see the guns of Ft. Ticonderoga pointed their way.

Washington now hopes that Howe will come out to attack him, but with Howe’s fleet vulnerable to the shore batteries, evacuation becomes the only option. On March 8, Howe signals Washington that he will not burn Boston if he is allowed to leave unmolested. Washington accedes, and on March 17, 120 craft carry 8,900 troops and just over 2,000 women, children, and Loyalists out to sea, headed for Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Boston is now back in the hands of the rebels.

July 4, 1776

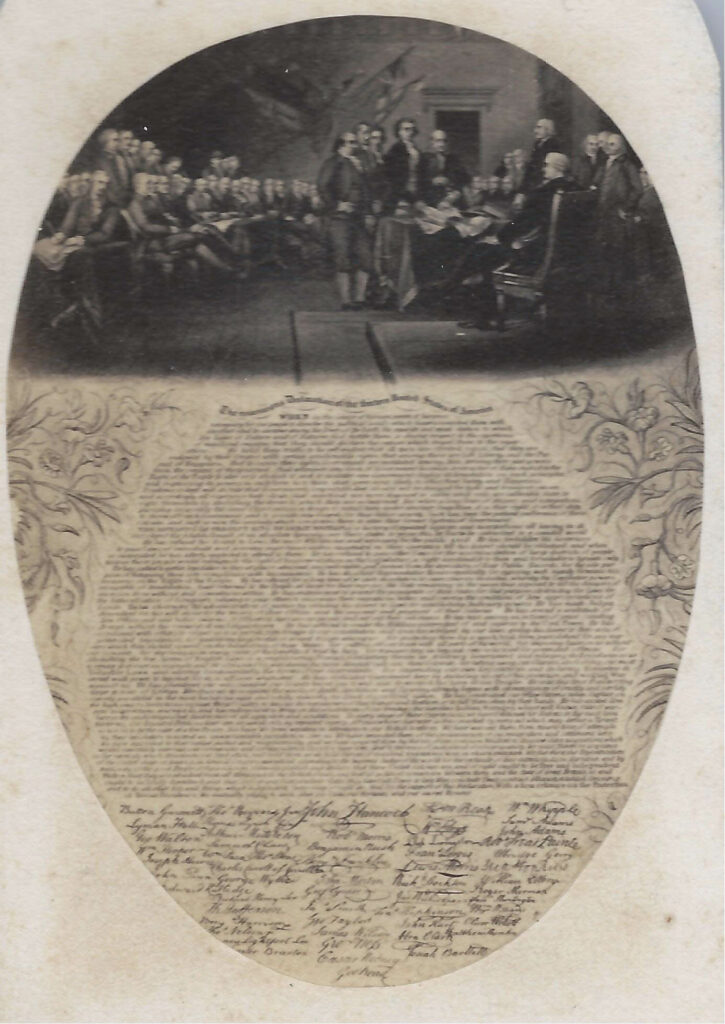

The Second Continental Congress Declares American Independence

The summer of 1776 marks fifteen months since the outbreak of fighting at Concord—fifteen months in which the colonies have governed themselves and roughly held their own in battle against the British Regulars.

Driven by these tailwinds, the “radicals” at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia are ready to force the issue of a final break with the crown.

The move is reinforced by a widely circulated pamphlet titled Common Sense, written by Thomas Paine, formerly a disgruntled tax collector in Britain.

Paine emigrates to Philadelphia in 1774 on the advice of Ben Franklin, with whom he shares a penchant for science, invention, and journalism. He becomes editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine and soon takes up the cause of the American rebellion. Paine is a visionary, and his stirring rhetoric touches the colonists.

We have it in our power to begin the world over again.

On June 7, 1776, Virginian Richard Henry Lee, who works for hand in glove over time with John Adams of Massachusetts, offers a resolution to that effect.

Resolved: That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

Seven states immediately support Lee’s resolution, but six others waver, which leads to a three-week hiatus as delegates return home for further local debate.

In the interim, the remaining delegates set up a series of “writing committees” to draft documents directed at gaining credibility and worldwide acceptance for a new nation.

First and foremost is a Declaration of Independence, assigned to a Committee of Five, including John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, Ben Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson, who pens a first draft.

The tone is restrained and appropriately respectful for an audience including the world’s hereditary monarchs—George III in England, Louis XVI in France, Charles III in Spain, and Frederick II in Prussia—all of whom will be threatened by the content.

It begins with a statement of overall purpose—to explain why America is breaking away from the crown.

When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bonds which have connected them with another, and to assume…the separate station to which the laws of nature entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes…of the separation.

From there, it sets out a series of beliefs about the nature of man and of government. These beliefs ring out with bold Enlightenment assertions. That all men are born free, and that natural law endows each with an equal right to seek happiness. That the role of government is to support this quest. That the form of government is up to the will of the people and that they may change it any time it fails to meet their needs.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter and abolish it, and to institute new government laying its foundation on principles…most likely to effect their safety and happiness.

The declaration then moves into a bill of particulars, in effect a formal indictment of the ways in which the king and the British government in the colonies have jeopardized the well-being of the citizenry. The list includes 27 separate counts, among them refusal to pass necessary statutes, obstruction of justice, imposition of taxes without consent, maintaining a standing army in times of peace, arbitrarily suspending local legislatures, cutting off trade with countries abroad, abolishing charters, imposing martial law, and “plundering our seas, ravaging our coasts, burning our towns, and destroying the lives of our people.”

All attempts at redress have failed, leading on to a conclusion:

A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a tyrant is unfit to be the ruler of a free people…We, therefore, the representatives of the united States of America…declare that…these United Colonies…are free and independent States…absolved from all allegiances to the British Crown.

And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor.

The document runs to only 1,337 words, and Jefferson’s original draft has been heavily edited by delegates, including the memorable opening sentence

| Jefferson’s Original | Final Resolution |

| We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable that all men are created equal & independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights, inherent & unalienable, that among which are the preservation of life & liberty and the pursuit of happiness. | We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. |

With a final declaration in hand, on July 2, a second vote is taken on the Lee resolution with Pennsylvania and New York still hanging in the balance. When both vote “aye,” the motion passes, and the break with Britain becomes official.

Two days later, on July 4, delegates sign the formal Declaration of Independence and the new nation is born. Once this declaration is made public, Franklin tells his colleagues, “…now we must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

Sidebar: A Glaring Deletion Regarding Slavery

Amidst the back and forth editing that goes into the final declaration, one other change in Jefferson’s original draft will come back to haunt the conscience of the new nation through the ages.

It occurs in the original list of “indictments” against King George—the charge being that he has been responsible for introducing and sustaining slavery in the colonies.

He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither.

This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian King, determined to keep open a market where men should be bought & sold.

He has…suppressed every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce.

He is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase the liberty of which he has deprived them by murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.

Jefferson’s language here is unequivocal.

Slavery is a “crime” committed upon “men” which “violates their sacred rights to life and liberty”—it is an “execrable commerce” which the colonists have tried to “prohibit or restrain.”

The irony is not lost that Jefferson himself is a lifetime slave owner, as are very many of the leaders of the Second Continental Congress. One can never know what internal debates took place in Jefferson’s mind as he wrote these words—nor in the minds of the delegates who had to consider them. But the fact remains that the final declaration deleted this paragraph on slavery in its entirety. Perhaps in seeking to indict the king over slavery, too many attendees felt they were indicting themselves.

July 12, 1776

Work Begins on the Articles of Confederation

Along with the declaration, a separate group of delegates, the Committee of Thirteen, begins work on how a “government of and for the people” will operate in practice. This committee is chaired by John Dickinson, who authored the Olive Branch Petition a year earlier.

From the beginning the committee and the delegates as a whole are divided over one central issue: the proper size and power of the central government. The two sides become known as Federalists and Anti-Federalists, and each is well represented in the Congress.

Prominent Divisions Over Federalism

| “Federalists” | “Anti-Federalists” |

|---|---|

| John Adams | Sam Adams |

| Alexander Hamilton | George Clinton |

| John Jay | Christopher Gadsden |

| Thomas McKean | Eldridge Gerry |

| James Madison | John Hancock |

| Robert Morris | Benjamin Harrison |

| George Read | Patrick Henry |

| John Rutledge | Thomas Jefferson |

| Roger Sherman | Richard Henry Lee |

| George Washington | George Mason |

The “Federalist” faction argues that a strong central government is needed to create a sense of unity throughout the country, and to act with one purpose in foreign affairs—especially during the current war with Britain.

The “Anti-Federalists” feel that a powerful center compromises the essence of what the rebellion is all about—enabling the common men to decide what government actions best suit their needs at the local level. In turn they argue that a strong center will end up like a monarchy—with a distant aristocracy of elites, focused on their own agenda, spending and taxing at will, overruling the wishes of individual states and local citizens.

This debate, however, is far too complex and potentially divisive to resolve in the middle of a war for survival, so the delegates put it off for the moment. Instead, the committee comes forward on July 12 with thirteen Articles of Confederation, summed up as follows:

- The new nation will be referred to as The United States of America.

- Each state will retain control of governing itself, except where specific powers are ceded to the federal level.

- The whole will act together to insure their common defense, secure liberties, and support general welfare.

- Citizens will be free to cross state lines and enjoy fair treatment; criminals will be extradited back home.

- Each state will have one vote in a Congress of the Confederation, and 2-7 delegates chosen by the legislature.

- The central government alone conducts foreign policy, declares war, and establishes commercial treaties.

- State militias will be maintained with officers named by the legislature and called out for common defense.

- Central government funding will come from the states, apportioned on assessed real property values.

- Congress declares war, approves treaties, names diplomats, resolves interstate disputes, defines coinage.

- A quorum of nine of the thirteen states is required for Congress to take action.

- If Canada decides to join the Confederation, it will be admitted.

- The Confederation is accountable for paying war debts accumulated before its existence.

- The above articles are perpetual and can be changed only if Congress approves and the states then ratify.

Aside from failing to resolve the broad philosophical issue of federalism, a host of other shortcomings related to the articles will become apparent over time. Rules affecting international commerce have not been spelled out. Plans to set and collect taxes remain iffy, and the government is perpetually underfunded. Perhaps most critical in the short run, the center is given little control over individual states when it comes to supplying troops, funds and materials to prosecute the war.

The entire document defining the thirteen articles runs to only five pages, and begs for greater detail on every point. Final ratification will drag on. Ten states ratify the articles within two years; the last state to approve, Maryland, doesn’t do so until February 1781, almost five years later.

Still the articles, while not “official,” will provide the framework for governing the new nation forward from July, 1776.

They must do for now. Time for talking is up; time for intensified fighting is on the way.