Section #4 - Early sectional conflicts over expanding slavery lead to the Missouri Compromise Of 1820

Chapter 43: The Black Experience In 1820

By 1820

The Slave Population Is Concentrated In The South And West

As of 1820, there are a total of 1.77 million blacks in America, or 18.4% of the entire population. Almost nine out of ten of them are enslaved.

Total US Population In 1820 By Race

| (000) | % Total | |

| Total US Population | 9,638 | 100.0% |

| Total White | 7867 | 81.6 |

| Total Black | 1,771 | 18.4 |

| Slaves | 1,538 | 16.0 |

| Free | 233 | 2.4 |

But only 117,000 blacks — or 6.6% of the 1.77 million – now reside in the North.

The eight original Northern states account for just under 110,000 blacks – with some 90,000 “classified” as freedmen and only 18,000 as slaves. Almost all of them are located in New York and New Jersey, where emancipation progress at a gradual pace.

The Black Population In The Original Northeastern States In 1820

| NY | Pa | NJ | Conn | Mass | RI | VT | NH | Total | |

| Slaves | 10,088 | 211 | 7,557 | 97 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 18,001 |

| Free Blacks | 29,275 | 30,202 | 12,460 | 7,870 | 6,740 | 3,554 | 903 | 786 | 91,790 |

| Total | 39,363 | 30,413 | 20,017 | 7,967 | 6,740 | 3,602 | 903 | 786 | 109,791 |

| Tot Pop | 1,372,812 | 1,049,458 | 277,575 | 275,248 | 523,287 | 83,059 | 235,981 | 244,161 | 4.061,581 |

The three new states to the west – Ohio, Indiana and Illinois – have all written constitutions and local “codes” to keep blacks out. These tactics succeed, and in 1820, their total count is only 7,500 blacks – or less than 1% of all residents.

Black Population In Three New NW States: 1820

| Ohio | Ind | IL | Total | |

| Slaves | 0 | 190 | 917 | 1,107 |

| Free Blacks | 4,723 | 1,230 | 457 | 6,410 |

| Total | 4,723 | 1,420 | 1,374 | 7,517 |

| Tot Pop | 581,434 | 147,178 | 55,211 | 783.823 |

Meanwhile, 93.4% of all blacks are living in the South – and making up sizable percentages of total state population.

In the original six states below the Mason-Dixon Line, just over 4 out of every 10 people are enslaved, on average. In South Carolina, Virginia and Georgia whites and blacks are about equal in numbers. In the two Border states of Maryland and Delaware, the ration of blacks to whites is about one in four.

The Black Population In The Southern And Border States In 1820

| Va | SC | NC | Ga | Md | Del | Total | |

| Slaves | 425,153 | 251,783 | 205,017 | 149,656 | 107,398 | 4,509 | 1,143,516 |

| Free Blacks | 23,493 | 13,518 | 14,612 | 1,763 | 3,681 | 12,958 | 70,025 |

| Total | 448,646 | 265,301 | 219,629 | 151,419 | 111,079 | 17,467 | 1,213,541 |

| Tot Pop | 938,261 | 502,741 | 638,829 | 340,989 | 407,350 | 72,749 | 2,909,919 |

But what is most striking about the slave population in the South is an accelerated migration to the new states west of the Appalachians.

The driving force here is the economy, with new western plantations starting up and increasing the “demand” for more slave labor. In turn, this “market” is being met by eastern owners who discover the windfall profits available in “breeding and selling their inventory of excess slaves.”

By 1820, just over 500,000 slaves have appeared in states from Kentucky to Louisiana, and this will prove to be only the start of the “rush.”

Slave Population In Western States (000)

| State | 1790 | 1820 | Growth |

| Kentucky | 12.4 | 126.7 | 10x |

| Tennessee | 0 | 80.0 | ++ |

| Georgia | 29.3 | 149.7 | 5x |

| Alabama | 0 | 47.4 | ++ |

| Mississippi | 0 | 32.8 | ++ |

| Louisiana | 0 | 69.1 | ++ |

| Total | 41.7 | 505.7 | 12x |

In the five western states below the Ohio River, nearly 3 in every 10 residents are slaves.

The Black Population In The Border And New Southern States In 1820

| Ky | Tenn | La | Ala | Miss | Total | |

| Slaves | 126,732 | 80,107 | 69,064 | 41,449 | 32,814 | 350,166 |

| Free Blacks | 2,759 | 2,737 | 10,476 | 1,001 | 458 | 17,431 |

| Total | 129,491 | 82,844 | 79,540 | 42,450 | 33,272 | 367,597 |

| Tot Pop | 564,317 | 422,823 | 153,407 | 127,901 | 75,448 | 1,343,896 |

1619 Forward

All Blacks Remain Denigrated And Feared

The upbeat vision of America in 1820 is not shared by the black population, be they enslaved or living as freed men and women.

Ever since their arrival in chains they have been dismissed as outcasts.

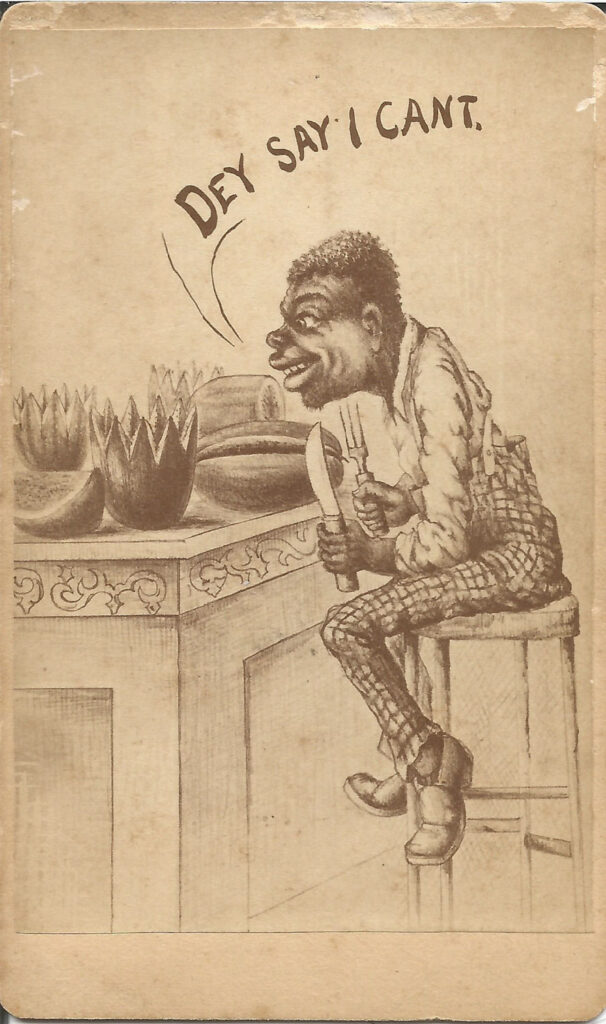

Everything about them — from their skin color to their geographic origins, language, manners and customs – sets them apart from the largely homogeneous white Anglo-Saxons who first settle the land.

As such, they personify “The Other,” a different tribe and likely a hostile one, to be subjugated and feared, not embraced.

Racial Stereotyping

Beyond that, arriving in shackles, they prick the consciences of those who have traveled to the new world in search of personal freedom and the moral teachings of their Christian faith.

Is their treatment, as slaves, consistent with the tenets of the Bible – or not? And, if not, is one in jeopardy of losing eternal salvation by participating in the abuses inherent in their captivity.

From these uncomfortable starting points, the human tendency to rationalize the status quo – especially when it is self-serving – outweighs the reservations, at least for the vast majority of whites focused on their own survival in a new land.

As with all forms of human atrocities, those in power come to rationalize their complicity. One, in particular, comes to symbolize this trait. He is President Thomas Jefferson, who appears particularly conflicted by his own thoughts and behavior toward “his blacks,” especially during his early years at Monticello.

This most complex man clearly recognizes the sin of slavery he is engaged in, but proceeds down the path anyway. He does so, in the end, by deciding that, indeed, blacks are The Other, a different and lesser species, somewhere above his cattle, perhaps the 3/5th of a man agreed to in the US Constitution – and certainly incapable of ever rising to equality with his own white race.

Jefferson of course is joined in this rationalization by seven of America’s first twelve Presidents – Washington, Madison, Monroe, Jackson, Tyler, Polk and Taylor – who, like him, will own slaves while in office.

By 1820, slavery has been in place for over two centuries and has achieved institutional status in the nation.

1820

The Daily Lives Of Those Enslaved In The South

The daily life of those enslaved differs dramatically, depending upon their assigned role on the farm or plantation. Some serve as field hands, others as house domestics. While both exist without precious freedom or respect, their fates are unequal.

House slaves – especially those directly serving the master and mistress — escape from the back breaking physical labor endured by the field hands. The women are assigned cleaning, cooking, sewing and gardening chores, along with tending to child care, as “mammy’s.” The men may act as butlers or footmen, tackle household repairs, care for horses and carriages. Both genders are often housed under their owner’s roof, have access to better clothing, diet, and medical care, and are exposed to the trappings of upscale white society and manners.

Since the grooming and behavior of house slaves can also be a reflection on the master’s wealth and magnanimity, they often become a chip in impressing visitors. Obedient and properly trained house servants signal a properly gentrified lifestyle.

On the other hand, the field hands are out of sight and often the province of hired overseers. Their measure of worth lies not in niceties, but in daily production of cotton.

A cotton crop planted around April 1 is ready to be harvested and sent to the ginning mill in July. An average field hand, bent over or crawling in the hot sun, might pick about 100 lbs. of cotton bolls a day, enough to fill up two 12-foot long “drag-along” sacks. After about 15 days of labor, the slave would have filled a standard 1500 lb. wagon, which would then be shipped to the ginning mill. After ginning, this wagon load would yield 500 lbs. of cotton fiber – or one finished “bale” – and 1000 lbs. of seed, for replanting or disposal. At a typical price of 20 cents a pound for fiber, the 500 lb. bale picked by the slave would sell for about $100 on the market.

Thomas Jones, a slave from North Carolina, captures the round-the-clock labor imposed seven days a week during the peak seasons.

During the planting and harvest season, we had to work early and late. The men and women were called at three o’clock ’n the morning, and were worked on the plantation till it was dark at night. After that they must prepare their food for supper and for the breakfast of the next day, and attend to other duties of their own dear homes. Parents would often have to work for their children at home, after each day’s protracted toil, till the middle of the night, and then snatch a few hours’ sleep’ to get strength for the heavy burdens of the next day.

No one is spared from this toil. Pregnant women work the fields. Older children are formed into gangs of weed pickers; younger children tote water from wells to workers.

During breaks, “slave food” is carried in pails to the fields. The typical diet is loaded with starch, in the form of cornmeal, and fatback, from salted pork. Access to vegetables and fruit goes to slaves lucky enough to maintain their own small garden plots.

Any perceived lapses in the daily toil are met by the wide range of punishments open to the bully over the defenseless. On one end is the lash, administered with a whip, tearing and scarring naked backs. On the other, the more subtle indignations, from cutbacks on rations to banning the smallest traces of freedom and dignity, like church gatherings.

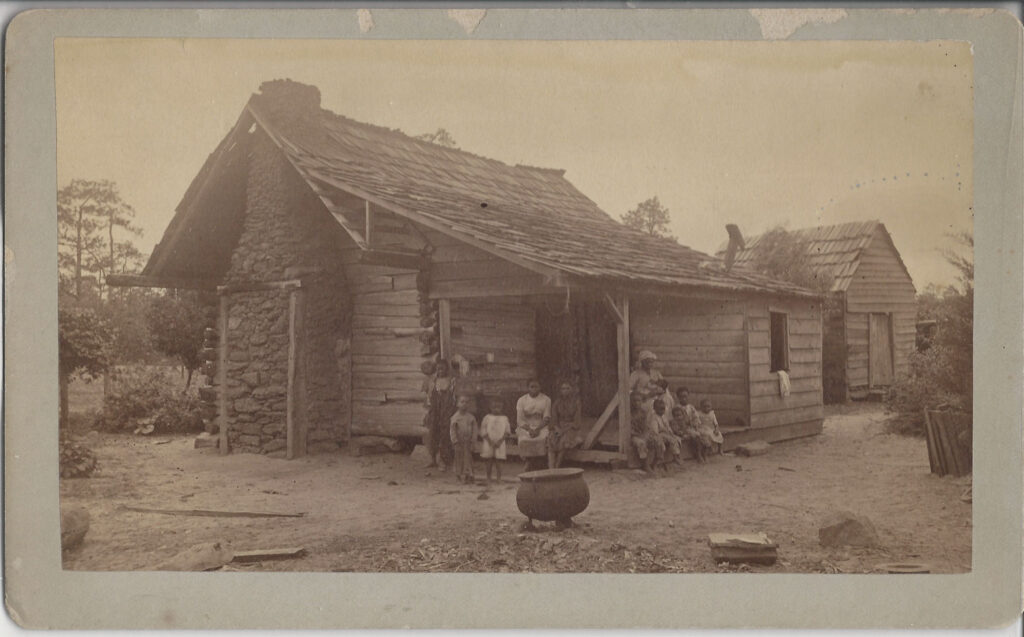

Field slaves live in dirt floor log cabins held together by clay-based mortar and vulnerable to rain in the summer and cold in the winter. Their dress is derived from flimsy “Negro cloth,” worn until disintegration. Many go shoeless; others wear “Negro brogans.”

Taken together, the living conditions for slaves leave them vulnerable to a host of killing diseases, including malaria, cholera, dysentery, tuberculosis and pneumonia. Mortality statistics bear this out – the death rate for slave babies and children up to age 14 being twice as high as for their white counterparts.

Thus, while plantation owners always wish to expand their “crop of slaves,” the daily treatment they afford them backfires – and across the antebellum period, life expectancy at birth is only 21 years as opposed to the 42 years averaged by whites.

1790’s Forward

Freed Blacks Inch Toward Respect

In 1820 there are roughly 233,000 “free blacks” in America, with some 98,000 in the North and 135,000 in the South.

Freedom has come to them in a host of ways: military service in the War of 1812, buy-outs, manumission, “passing for white,” northern laws abolishing slavery now or for new births.

Roughly two-thirds of free blacks are females, often left to fend for themselves, frequently with children in tow fathered by men who remain in slavery. The result here being a matriarchal cast to the society created.

While theoretically free, local “black codes” circumscribe their daily lives.

Failure to produce papers proving their freedom can return them directly to bondage. In the South, their homes often abut plantations, and some continue to live in slave quarters. In the North, they typically find themselves in cities, segregated into all-black neighborhoods, labeled by names like “Darktown” or “Shantytown.”

The first challenge facing these free blacks lies in simple economic survival.

Many of them, especially the women, transition from slavery into domestic servitude.

Others, especially men, try to scratch out a living as day laborers, draymen, porters and the like.

A few begin to the move up the economic ladder by acquiring special know-how and skills always in demand.

Self-taught skills such as barbering, hairstyling, sewing and tailoring become popular occupations among free blacks. Some wrangle apprenticeships and find work as blacksmiths, saddlers, carpenters, masons, butchers or shoemakers. Access to professional or white-collar jobs, however, is sharply limited by historical prohibitions against teaching them to read, write or master numbers.

Despite all of these hurdles, blacks who have escaped enslavement begin to inch their way into the white dominated social structure they encounter. Men like Prince Hall, Paul Cuffee and James Forten demonstrate the talent and tenaciousness to achieve economic success and work on behalf of others in the black community.

Black churches in particular provide a refuge from daily oppressions and a place to advance survival skills.

Indeed. the gradual movement toward “coloured citizenship” will be shaped inside Thomas Paul’s Boston church, the 1819 African Methodist Episcopal Church founded in Philadelphia by Reverend Richard Allen, Samuel Cornish’s First Colored Presbyterian Church of New York (1821), the African-American Church of Charleston (1822), the First Black Baptist Church of New Orleans (1826) and others.

1820

The Roll Call Of Black Abolitionists In 1820

Among the early black fighters for freedom and citizenship, three notables – Prince Hall, Paul Cuffee, and Absalom Jones, have passed from the scene by 1820.

A Few Early Black Abolitionists Who Have Passed By 1820

| Death | At Age | |

| Prince Hall | December 4, 1807 | 72 |

| Paul Cuffee | September 9, 1817 | 58 |

| Reverend Absalom Jones | February 13, 1818 | 72 |

But James Forten remains, as does the Reverend Thomas Paul – and they are about to be joined by a next generation of reformers who will advance the cause in the decades ahead.

Early Black Abolitionists Still Alive In 1820

| Age In 1820 | |

| James Forten | 56 |

| Reverend Thomas Paul | 47 |

| Austin Steward | 27 |

| Thomas Dalton | 26 |

| Reverend Samuel Cornish | 25 |

| Reverend Theodor Wright | 23 |

| Sojourner Truth | 23 |

| David Walker | 22 |

1820

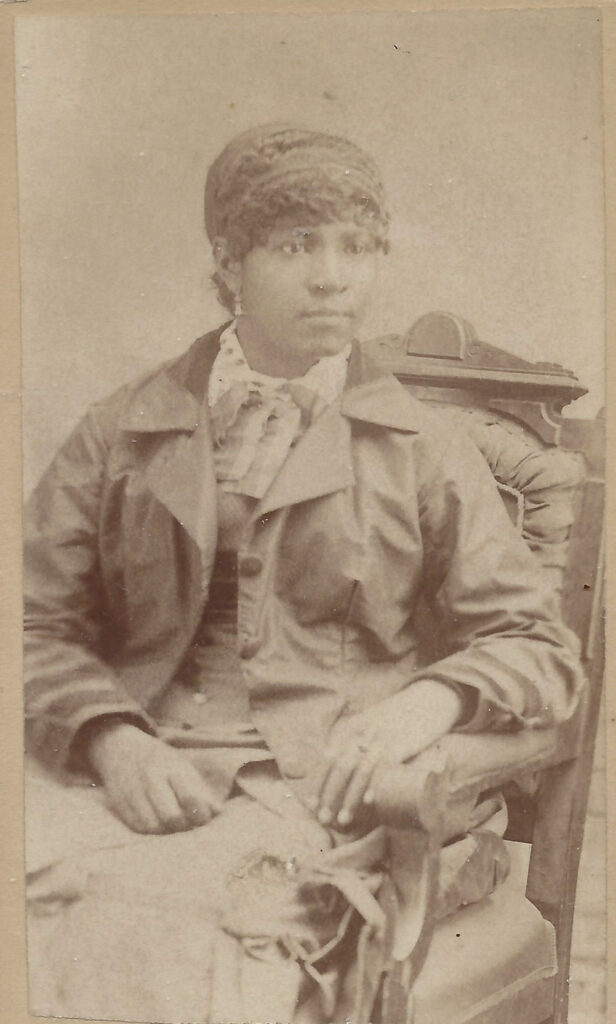

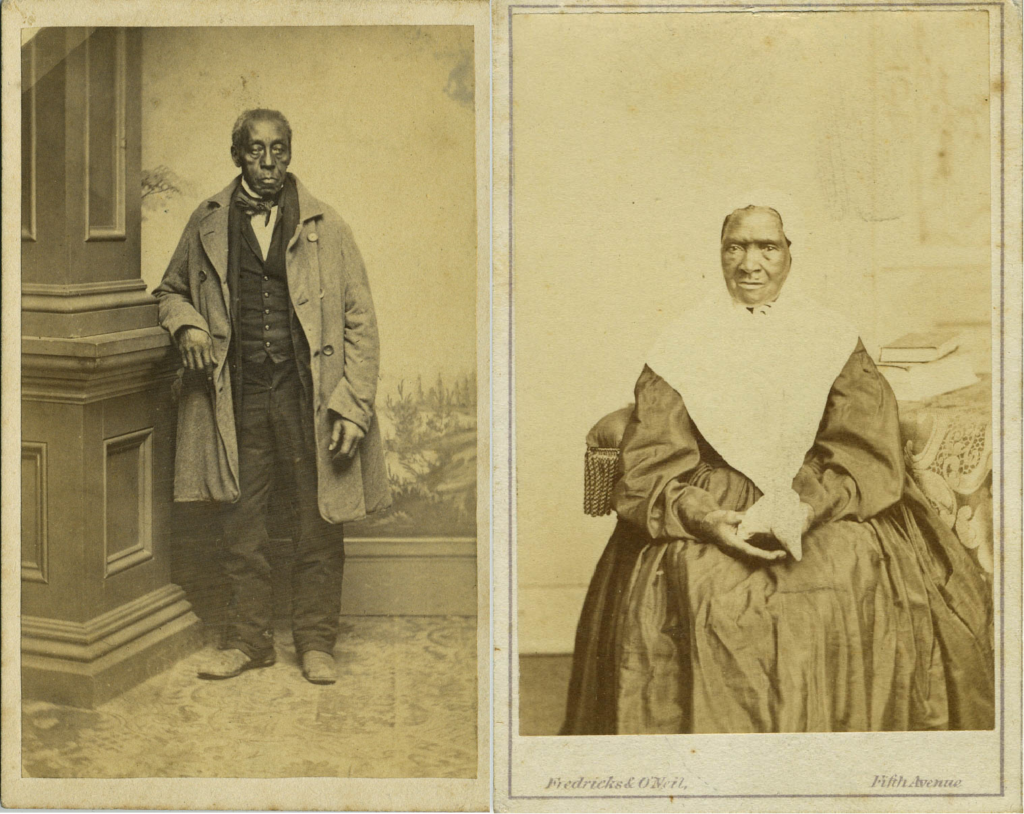

Sidebar: Old Fanny, Uncle Abraham And The Lott Family Of Brooklyn

LEFT: “Uncle Abraham”

One destiny for slaves freed in the North lay in ongoing servitude to their former owners – and such was the case with “Old Fanny” and “Uncle Abraham” of the Lott household in Brooklyn.

The Lott family migrates from Holland to New York around 1630. At the time, slave ownership is widespread among the Dutch, with blacks originally comprising about 20% of the state’s population. In New York city over half of all residents own at least one slave, and the Lott family owns twelve, according to the 1790 census records.

In 1800 Hendrick I. Lott (1760-1840) builds a 22 room home on 245 acres of farmland in the Flatlands (Brooklyn) and moves in with his wife, Mary Brownjohn, daughter of a prominent family also from New York city. One of their offspring, a son, Johannes, marries Gashe Bergen in 1817, and fathers seven children. One is Henry DeWitt Lott (b. 1820), another, Eliza Lott (b.1828).

At some point, Henry Lott comes to own the slave Abraham, while Eliza owns Fanny.

And at some point, Abraham weds Fanny, and they have at least one child, a daughter, Fannie Lew, who is owned by Elsie (Ray) Lott.

When slavery finally withers away around 1830 in New York, Abraham and Fanny transition from slaves to “coloured servants” of Henry and Eliza.

A trip into New York City by Eliza probably prompts the photograph above, taken by Fredericks & O’Neill of 5th Avenue, of an aging “Old Fanny,” standing beside the seated “Lizzie.” By the time it is taken, “Uncle Abraham,” whose photo originates at Isley’s Studio in Jersey City, has presumably passed away.

The Lott property remains a NYC landmark to this day, and restoration work shows that the slave quarters were well hidden within the building through a trap door in the kitchen. Artifacts found in this space include candle drippings, a mortared-over oven, a cloth pouch, oyster shell and corncobs, the latter arranged in a starburst pattern suggesting that they were used as part of West African religious rituals.

Conjecture also has it that a secret 6’x12’ room concealed behind a closet on the second floor of the Lott house may have been used in the 1840’s by run-away slaves moving north along the Underground Railroad.

Over 150 years have passed since Aunt Lizzie and “Old Fanny” posed for the camera, on their visit to NYC. But there they are, captured in time, forever symbolizing a limbo-like moment where some black people in America were no longer slaves, but not nearly all the way free and equal.