Section #21 - A North-South Split in the Democrat Party leads to a Republican Party victory in 1860

Chapter 254: The 1860 Campaign For President

Fall of 1860

The 1860 Race Is Unique In American History

The 1860 campaign for President is unique in America’s history, and it sets the stage for the break-up of the Union which follows.

Never before has the country been confronted with more than three sizable political parties in a presidential race.

Historical # Of Parties Competing For President

| Year | Parties |

| 1832 | Democrats + National Republicans + Nullifiers |

| 1836 | Democrats + Whigs |

| 1840 | Democrats + Whigs |

| 1844 | Democrats + Whigs + Liberty |

| 1848 | Democrats + Whigs + Free Soil |

| 1852 | Democrats + Whigs + Free Soil |

| 1856 | Democrats + Republicans + Know Nothings |

In 1860, there are suddenly four separate political parties, each offering distinct platforms and reasonably credible candidates.

The Four Party Presidential Race Of 1860

| Candidates | Party | Main Platform Promise |

| Abraham Lincoln | Republican | Ban slavery in the western Territories |

| Stephen Douglas | North Democrats | Rely on popular sovereignty to decide |

| John Breckinridge | South Democrats | Pass a Congressional Bill to protect slavery nationwide |

| John Bell | Constitutional Union | Seek a new compromise that preserves the Union |

On top of that, this becomes the first election since James Monroe in 1820 where the outcome is almost a certainty before the first ballot is cast.

The man destined to be chosen is Abraham Lincoln, assuming he can simply carry nearly all of the 183 electoral votes available in the North, based on his, and the Republican’s, opposition to the presence of slaves (or even “free blacks”) in the new territories.

Allocation Of Electoral Vote In 1860

| Section | # |

| North/Free States | 183 |

| South/Slave States | 120 |

| Total | 303 |

| Needed To Win | 152 |

Of course this kind of regional clean sweep has never happened in the era of two or more competing parties.

Prior campaigns have always been waged on a national basis, at least by the major parties, and past Presidents have always been able to carry at least five Free States and five Slave States.

Free And Slave States Won In Prior Presidential Elections

| Year | Winner | Total States | # States Won | # Free States | # Slave States |

| 1828 | Jackson | 24 | 15 | 5 | 10 |

| 1832 | Jackson | 24 | 16 | 8 | 8 |

| 1836 | Van Buren | 26 | 15 | 8 | 7 |

| 1840 | Harrison | 26 | 19 | 14 | 5 |

| 1844 | Polk | 26 | 15 | 7 | 8 |

| 1848 | Taylor | 30 | 15 | 8 | 7 |

| 1852 | Pierce | 31 | 27 | 16 | 11 |

| 1856 | Buchanan | 31 | 19 | 5 | 14 |

But this pattern changes in 1860, and with devastating results.

Fall of 1860

The Focus Is On The Northern States

Instead of a national election in 1860, the race comes down to two separate sectional contests:

- In the North, a “stop Lincoln” effort to throw the election into the House of Representatives; and

- In the South, a largely irrelevant run-off between Breckinridge and Bell.

The Republican strategy is to concentrate exclusively in the North, knowing that their platform banning slavery in the west will be rejected out of hand in the South – and that trying to campaign there would be a waste of time and money.

While smart in the short-run, this strategy will negatively affect Lincoln when he enters office. At that point he will remain a total mystery to people across the South. They will never see that he is a Kentuckian by birth; a loyal protégé of the Great Compromiser, Henry Clay; not a radical abolitionist; an outspoken opponent of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry; a strict believer in the Constitution and the inviolable right of the old South to maintain slavery; a friend of the powerful Georgian Democrat Alexander Stephens (later the Confederate Vice-President), and one who wishes intensely to maintain the sacred Union. All of this “missing information” will weaken Lincoln’s capacity to hold the nation together after he is elected.

Lincoln’s opponents meanwhile concentrate on stopping his steamroller across the North.

Early in the campaign, even his long-term adversary, Stephen Douglas, is convinced that he cannot derail Lincoln by himself. The result is a joint agreement between the Little Giant and the two Southern candidates to construct what are known as “fusion ballots.” These are intended to allow Northern voters who oppose Lincoln to choose a “generic alternative” representing “electors” for Douglas or Breckinridge or Bell.

If the total ballots cast for the “fusion candidate” were to exceed those for Lincoln in a given state, the effect would be to deny him some or all of its electoral votes needed for a majority.

Representatives of Douglas, Breckinridge and Bell agree to construct these “fusion ballots” in three Northern states where they think Lincoln might be vulnerable: Pennsylvania (with 27 electoral votes), New Jersey (7 votes) and New York (35 votes).

In the end, this strategy succeeds only in the least important state, New Jersey, where the “fusion ballots” is chosen by 51.9% of the votes. Despite this outcome, four of the top seven vote counts for the “electors” listed belong to Lincoln, while the other three are for Douglas – thus giving Lincoln a 4-3 win in the Electoral College.

Popular Votes For President In 1860 In “Fusion” States

| States | Lincoln | “Fusion” | Other |

| New York | 53.7% | 46.3% | 0.0% |

| Pennsylvania | 56.3 | 37.5 | 6.2 |

| New Jersey | 48.1 | 51.9 | 0.0 |

Sidebar: Ballots And Voting In The 1860 Election

It is not until the election of 1888 that Americans vote by going to a secure polling place, being handed a pre-printed ballot listing all candidates side by side for given federal or state offices, marking their choices in secret, and placing them in a locked ballot box.

Before that, the process is much more chaotic and prone to manipulations and even fraud.

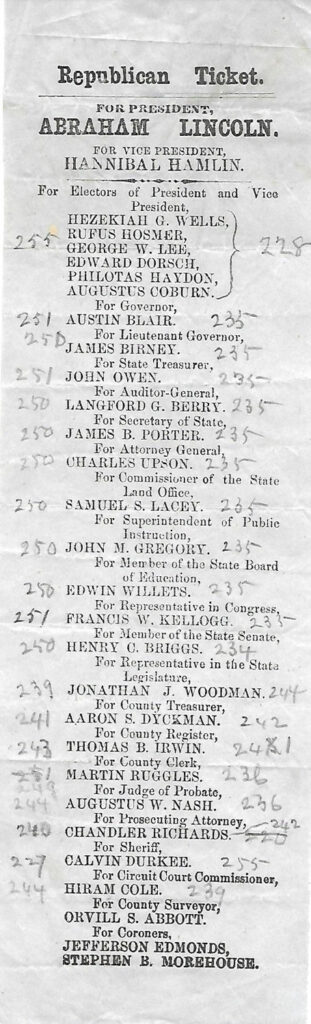

Thus in 1860, each party is responsible for naming their slate of candidates, then printing up paper ballots, and distributing them to the public in newspapers (to be clipped out) or via “peddlers” who hand them out at the polling places. A voter would secure the ballot for their favored candidate, then enter the polling place and put this slip of paper in a box. “Poll judges,” often appointed by the party in power, are present to hopefully recognize local voters and to insure that only one ballot was cast per person.

Most of the ballots are constructed like the one shown here – with one set of candidates listed for President and Vice President, and their “designated electors” shown below.

But the law also allows for so-called “fusion ballots,” often with a “generic” title such as “Opposition Parties.” These list a pre-set number of “electors” for each of the two or three candidates who have agreed to appear together on the same ballot. This was the case, for example, in the state of New Jersey, where all three of Lincoln’s opponents joined the “fusion” – in this case with Douglas naming three electors and Breckinridge and Bell listing two each.

The intent of this “fusion ballot” was to try to deny Lincoln the majority needed in a given state to win all of its electoral votes.

An 1860 Republican Ballot From Ohio In 1860, this strategy failed in New York and Pennsylvania, while succeeding in New Jersey, where Lincoln won 48% versus 52% for the “Fusion” of Douglas, Breckinridge and Bell.

Fall of 1860

The Campaign Is Lively From Start to Finish

The importance of the 1860 election is obvious to all, and 4 out of 5 citizens will eventually turn out to vote.

Three of the four candidates remain aloof from personal campaigning, thus conforming to the old dictate that “the office seeks out the man and not vice versa.” The exception is Douglas, who stumps on his own behalf throughout much of the run-up period.

Surrogate speakers are the norm for Lincoln, Breckinridge and Bell, along with fiery editorials from the roughly 327 newspapers extant at the time, many propaganda machines for state and local party bosses.

Endorsements are also sought and gotten, perhaps most notably from Presidents Buchanan and Pierce, two doughfaces who back Breckinridge to little avail.

Armies of followers line up to promote their favorites and to have a rollicking good time in the process.

Lincoln’s forces are the “Wide-Awakes,” carrying oil lamps to light the way, wearing treated capes to prevent the inevitable dripping from staining their clothes. As they march they sing “Lincoln & Liberty Too” to the beat of “the old grey mare:”

Old Abe Lincoln/Came out of the wilderness/Out of the wilderness/out of the wilderness, Old Abe Lincoln/Came out of the wilderness/Down in Illinois.

They personify the man himself as “Honest Old Abe – The people’s choice” and “the Rail Splitter of the West.” Their parades are marked by six-foot spheres of cloth and tape which they roll down the streets shouting “The Republican ball is in motion.” In more serious moments they offer slogans: “Vote Yourself A Farm” and “Protection for American Industry” and “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Home.”

Predictably the Douglas backers cast themselves as “The Little Giants” and are eager to chant that “No Rail Splitter can split this Union” and “Popular Sovereignty/Let The People Rule.”

In frivolous moments, the dour Bell supporters become “Bell Ringers” before they morph back into “Minute Men” and “Union Sentinels” touting Daniel Webster’s line, “Liberty and Union, Now and Forever,”

The ever-serious Breckinridge has his “National Democratic Volunteers” who proclaim “Our Rights, The Constitution and The Union” – while Douglas counters “Breckinridge may not be for dis-union, but all the dis-unionists are for Breckinridge!”

Fall of 1860

Stephen Douglas Offers To Withdraw To Forestall Disunion

The one man at the center of the actual campaigning turns out to be Stephen Douglas, who will work initially on his own behalf before dedicating his remaining energy to trying to save the Union.

Douglas is only 47 years old at the time, but will be dead within a year, the victim of lifelong health issues, excessive drinking and a typically brutal public appearance schedule in 1860 that saps his remaining strength.

He is stunned in June 1860 by the break-up of his beloved Democratic Party at Charleston, but undeterred in his drive to once again compete against his arch-rival Lincoln, this time for the presidency. By July he announces his strategy in a letter to one of his supporters:

No time must be lost and no effort spared…We must make the war boldly against the Northern abolitionists and the Southern Disunionists, and give no quarter to either. We should treat the Bell & Everett men friendly and cultivate good relations with them, for they are Union men…(but) we can have not partnership with the Bolters.

At the same time, he is every bit as deluded as Lincoln about the sense of alienation spreading across the South. In his own mind, Douglas believes that he has been a good friend of the South, going all the way back to his earlier days in Congress, rooming at the “F-Street mess” with pro slavery men like the Missouri “ruffian,” David Atchison, James Mason and Robert M. T. Hunter of Virginia and Andrew Butler of South Carolina. His record of support includes the 1850 Compromise, the Kansas-Nebraska Act and his doctrine of popular sovereignty, the last ditch effort to combat the Republican effort to ban slavery in the western territories. Surely, he tells himself, these credits to the South should be enough to offset his refusal to go along with the bogus Lecompton Constitution in Kansas.

Within this frame of mind, he predicts in July that he will carry many Northern states along with seven in the South – when in fact, he will end up with only Missouri and a few electors in New Jersey.

Douglas’ Election Forecast For The South As Of July 1860

| Candidate | # Wins | States |

| Breckinridge | 2 | SC and perhaps Mississippi |

| Bell | 6 | Ky, Tenn, NC, Va, Md, Del |

| Douglas | 7 | MO, Ark, La, Tex, Ala, Ga, Fla. |

He departs on July 14 from disappointing fund raising efforts in New York, to stump across New England, with appearances in Boston, Albany and his birthplace, Vermont. The responses are lukewarm, and by August the New York Times predicts that Lincoln is certain to win, and his reluctant running mate, the Georgian Herschel Johnson, tells him: “I have not much hope for the future.”

But with his usual tenacity, Douglas heads South, into Virginia. When asked in Norfolk whether the South would be justified in seceding immediately, were Lincoln elected, he offers an unequivocal “no.” In Petersburg he tells his audience:

I am not here on an electioneering tour. I am here to make a plea, an appeal for the invincibility of the Constitution and the perpetuation of the Union.

On August 30 in Raleigh, North Carolina, he adds:

I know of but one mode of preserving the Union. That is to fight against all disunionists…The only mistake we Democrats made was in tolerating disunionist sentiments in our bosoms so long.

The more bleak his presidential prospects become, the more he turns to what he sees as his duty as a patriot to stave off secession. In the same vein as his opposition to accepting the Lecompton Constitution, Douglas now places the well-being of the nation above his own political ambition.

In early September he is up North in Pennsylvania where a key battle is under way between the Democrats and Republicans for Governor. On September 11 he meets with Herschel Johnson in New York, who tells him that he is unlikely to win any Southern states, and that various “stop Lincoln” men, including Jefferson Davis, are asking all three current candidates to step aside in favor of one alternative who might unite the opposition. Douglas is shocked and dismayed by Johnson’s alarms, but again refuses to drop out – although he does authorize an effort to create “fusion ballots” in several states.

He barrels forward to the west, through Cleveland and Cincinnati to Indianapolis on September 28, and then to Louisville. Observers comment on his voice (a “spastic bark’), the lemons he squeezes into his mouth to continue to speak, and the overall wear and tear on his frame.

The only wonder is that his health does not give way under the trials and fatigue he is compelled to endure in order to meet demands.

After passing through Chicago, he is off to Iowa, Wisconsin and Michigan. On October 9 he hears the devastating news from two early gubernatorial (October 9 polling) races. In the crucial state of Pennsylvania, Republican Andrew Curtin defeats Democrat Henry Foster by 53-47%, while in Indiana, the abolitionist Henry Lane bests the Democrat Thomas Hendricks by a 52- 48% margin. This ends all remaining hope for Douglas. Lincoln will be the next President and all that’s left is to try to throw himself against the looming threat of secession. He writes:

Mr. Lincoln is the next President. We must try to save the Union. I will go South.

On October 19, 1860, just eighteen days before the election, Douglas begins another southern swing which will take him through Memphis to Huntsville, Nashville, and Chattanooga and, on October 29, Atlanta, where Alexander Stephens introduces him to an assembled crowd. November 2 brings him to Montgomery, soon to be the capital of the Confederacy, followed by Mobile on November 5, where he makes his final address. For the most part, Douglas is treated respectfully by the Bell supporters while being roundly denounced by the Breckinridge men. His message is the same to both:

I believe there is a conspiracy on foot to break up this Union. It is the duty of every good citizen to frustrate the scheme.

On November 6 he will monitor the election results from Mobile, with a friend who records that he seems “more hopeless than I had ever before seen him.”

But in many ways, the Little Giant’s courageous march into the South during the campaign is his finest hour, both as a politician and patriot.

September 5, 1860

John Breckinridge Makes His One Speech During The Run-Up

Like the other three men in the race, Vice-President John Cabell Breckinridge declares that he is intensely committed to preserving the Union.

He makes this point in the one public speech he delivers during the campaign, at a rally on September 5, 1860 in Ashland, Kentucky. The talk rambles on for over three hours, with Breckinridge pausing at several intervals to ask the audience if they wish to hear more, the response being calls to continue.

He begins by asserting, properly, that he never sought to run for President, and is doing so only because “a particular individual” (Douglas) tried to foist a “pernicious doctrine” (popular sovereignty) on the delegates in Charleston and Baltimore.

I did not desire to be presented to the American people…(but) the most flagrant acts of injustice were perpetrated, for the purpose of forcing upon the Democratic organization a particular individual as the representative of a pernicious doctrine, which I shall be able to show is repugnant alike to reason and the Constitution.

He also runs to clear his name of false accusations that have been made – that he backed a pardon for John Brown, that he was a Know Nothing, that he opposed slavery like his famous preacher uncle Robert, that he favor emancipation. All wrong, he says, and goes on to define the core issue fueling the conflict.

It is contended, on one hand…that the citizens of the slaveholding States may remove to them with their slaves, and that the local legislature cannot rightfully exclude slavery while in the Territorial condition; but it is conceded that the people may establish or prohibit it when they come to exercise the power of a sovereign State. On the other hand, it is said that slavery, being in derogation of common right, can exist only by force of positive law; and it is denied that the Constitution furnishes this law for the Territories; and it is further claimed that the local legislature may establish or exclude it any time after the government is organized.

I did not hold the doctrine that a Territorial Legislature could exclude slave property from the Territory during the Territorial condition….I held precisely the opposite,

The Dred Scott ruling should have ended the slavery debate, by defining slaves as “property” pure and simple, with no distinction versus other forms of property.

Between slave property and other property, no distinction exists; property in slaves is recognized by the Constitution of the United States,…I am content to stand upon these principles, thus announced by the Supreme Court of the Union. After this decision, we had arrived at a point where we might reasonably expect tranquility and peace. The equality of rights of persons and property of all the States, in the common Territory, having been stamped by the seal of judicial authority, all good citizens might well acquiesce

Because the South will not give up their rights, they are being unfairly accused of being disunionists.

Because we will not bow down to a doctrine that deprives us of our rights, we are bolters, demagogues, secessionists, dis-unionists ! (Continued applause.)

Breckinridge asserts the two principles that capture his position on slavery in the territories:

I will read these two resolutions, and you can judge whether they accord with the Constitution, the decision of the Supreme Court, and the practice of the Government as I have shown it today :

1. Resolved, That the government of a Territory organized by an Act of Congress, is provisional and temporary, and during its existence all citizens of the United States have an equal right to settle with their property in the Territory, without their rights of either person or property being destroyed or impaired by Congressional or Territorial legislation.

2. That it is the duty of the Federal Government in all its departments to protect, when necessary, the rights of persons and property in the territories, and wherever else its constitutional authority extends.” These are two principles we avow

He cites support for his views from the icon of Kentucky politics, the 73 year old Senator, John Crittenden, and assures the listeners that acting on them will produce fairness and harmony between the States.

I derive some satisfaction from the fact that the Hon. John J. Crittenden, has declared, by his speeches and votes in the Senate, that the principles upon which we stand are constitutional and true. (Cheers.) Fellow-citizens, these principles will give us peace and prosperity; they will preserve the equality and restore the harmony of the States. They will make every man feel that in his personal rights and rights of property he stands on a footing of equality in the domain common to all the States? (Cheers.) They have their root in the Constitution, and no party can be sectional which maintains constitutional principles.

But Republicans refuse to accept the Constitution – they reject the words declaring “slaves are property” and deny owners the right to transport them into the territories free of risk. If their views prevail, it will “destroy the Union.”

The Republican organization holds precisely opposite principles. They say we have no rights in the territories with our property. They say Congress has a right to exclude it, and it is its duty to do so… (Lincoln’s) principles are clearly unconstitutional, and if the Republican Party should undertake to carry them out, they will destroy the Union.

After calling out a long list of opponents, he offers, interestingly, that he is “not ashamed” of his principles when it comes to slavery.

I am not ashamed of the principles upon which I stand. I am not ashamed of the reasons by which they are sustained. I am not ashamed of the friends that support me. I am not ashamed of the tone, bearing and character of our whole organization. (Applause. A voice — ” T’he truth will prevail.”)

On this note – that truth will prevail – he ends.

Yes, the truth will prevail. You may smother it for a time beneath the passion and prejudices of men, but those passions and prejudices will subside, and the truth will reappear as the rock re-appears above the receding tide. I believe this country will yet walk by the light of these principles…. People of Kentucky, you never abandoned a principle you believed to be right. You may be misled, but the stigma never rested on Kentucky that she abandoned principles she believed to be true. (Cries of, “We never will.”)

For myself, conscious that my foot is planted on the rock of the Constitution — surrounded and sustained by friends I love and cherish — holding principles that have been in every form indorsed by my native commonwealth — with a spirit erect and unbroken I defy all calumny, and calmly await the triumph of the truth. (Prolonged applause.)