Section #22 - The Southern States secede and the attack on Ft. Sumter signals the start of the Civil War

Chapter 271: Senate Resignations Provoke More Last Ditch Efforts To Preserve Peace

January 21, 1861

The First Ten Southern Senators Resign

As Southern states secede from the Union, so too do their representatives in Congress.

These departures have relatively little effect in the House, already dominated by Northerners. But in the Senate they will quickly begin to swing the balance of voting power to the Northern Republicans.

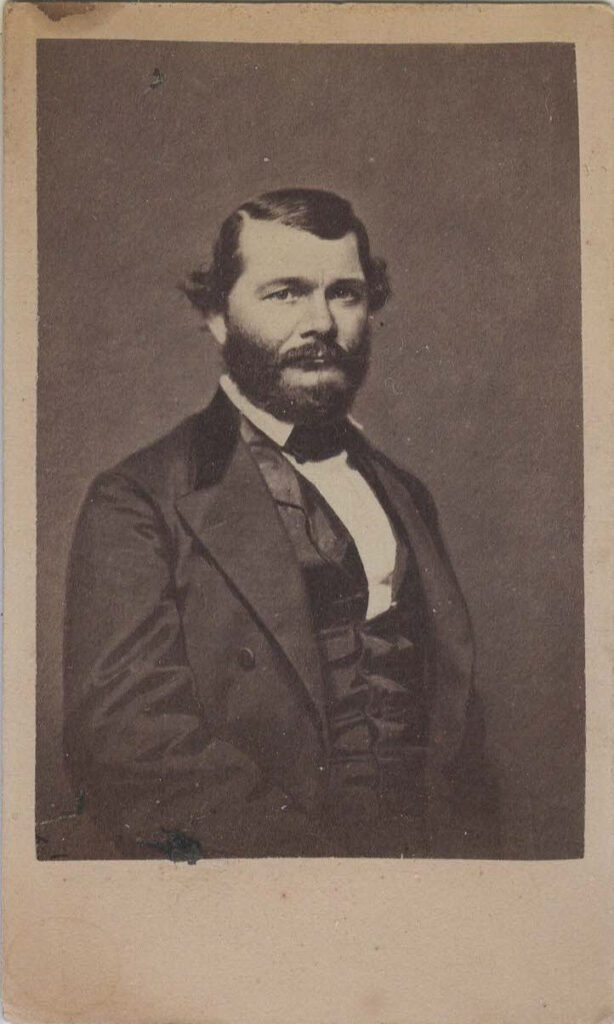

On January 21, the roster of exiting Southern Senators reaches nine – as Mississippi’s Jefferson Davis and Florida’s David Yulee and Stephen Mallory withdraw.

When Georgia’s Alfred Iverson departs a week later, he offers a stern warning to the North:

In whatever shape you attack us, we will fight you. You may whip us but we will not stay whipped.

January 21-24, 1861

The Politicians Continue Their Quest To Save The Union

Despite the dwindling odds, several long-time Washington politicians continue their efforts to save the Union.

To most it appears certain that the seven states across the Lower South – from South Carolina through Texas – will secede.

But that still leaves eight other Slave States yet to decide, including Virginia, seemingly a bellwether for the Upper South. If a plan can be worked out to retain this group, perhaps it will prompt the others to consider a peaceful return.

Various political insiders take up this cause.

One is Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin, a southern sympathizer, who eventually supports the “neutrality status” favored by the state assembly when the war breaks out. Magoffin tries to rally support for a constitutional amendment to repeal any state laws opposing enforcement of the fugitive slave act.

When this fails, Magoffin lines up behind his fellow Kentuckian, John J. Crittenden, who continues to believe that a national referendum will show that the public prefers his plan to Disunion and the prospect of civil war.

On January 21, 1861, Crittenden’s surrogate in the House, Indiana’s William English, puts the legislation up for a vote. The resounding 92-60 rejection is another blow for all bills – including the prior “Henry Davis Winter Compromise” – that hinge on extending the old 36’30” demarcation line to the west coast. Even the tenacious Tom Corwin of Ohio begins to despair:

If the States are no more harmonious in their feelings and opinions than these…representative men, then appalling as the idea is, we must dissolve & a long & bloody civil war must follow. I cannot comprehend the madness of the times….God alone I fear can help us.

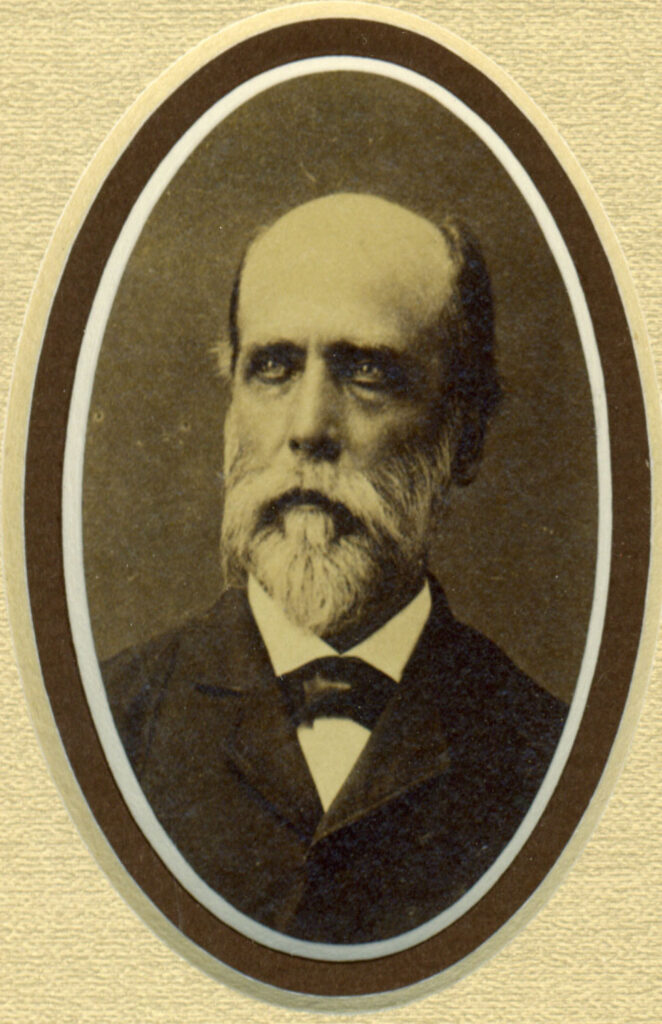

But then another septuagenarian, ex-President John Tyler of Virginia, volunteers to try his hand at a solution.

The controversial Tyler has been out of politics for fifteen years, after becoming the nation’s first “accidental President” upon the death in 1841 of William Henry Harrison. While elected as a Whig, Tyler’s policy actions in office favor the Democrats, and by 1842 he is regarded as a turncoat. Neither party will run him for re-election in 1844, and he heads home to plantation life along the James River.

On January 24, however, he is back in Washington, calling upon Buchanan and urging him to support a Peace Conference he is arranging for February 4 to consider a “Virginia Plan” to save the Union.

The President ultimately agrees to go along with Tyler’s proposal.