Section #9 - Growing opposition to slavery triggers domestic violence and a schism in America’s churches

Chapter 93: Selling Slaves

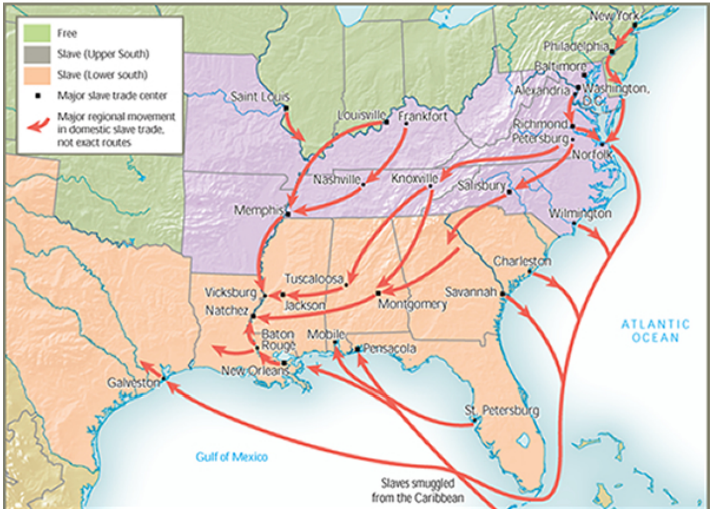

Shipment Of Slaves To The West

The ultimate destinations for the “excess” slaves being bred are the new cotton plantations opening up west of the Appalachian range.

Thus the staggering growth in the slave population already occurring between 1820 and 1840 in states such as Mississippi (+595%), Missouri (+582%) and Alabama (+535%), along with the more than doubling recorded in Louisiana (+144%), and Tennessee (+128%), with Georgia (+88%) just behind.

The leading “supplier states” for these western slaves is Virginia, with its very large black population (over 425,000 in 1820) and its need to address lagging profits on its tobacco plantations.

Other “slave breeder/supplier states” include North Carolina (also suffering erosion in its principal tobacco crops), South Carolina (the “rice kingdom,” but with most suitable lowlands already owned), and the two border states, Delaware (where only 2,600 slaves remain) and Maryland.

Changes In Slave Populations By State

| Old South | Statehood | 1820 | 1840 | Change | % Ch |

| South Carolina | 1788 | 251,800 | 327,000 | 75,200 | 30 |

| Georgia | 1788 | 149,000 | 280,900 | 131,900 | 88 |

| Virginia | 1788 | 425,200 | 449,100 | 23,900 | 6 |

| North Carolina | 1789 | 205,000 | 245,800 | 40,800 | 20 |

| Border States | |||||

| Delaware | 1787 | 4,500 | 2,600 | (1,900) | (42) |

| Maryland | 1788 | 107,400 | 89,700 | (17,700) | (16) |

| Kentucky | 1792 | 126,700 | 182,200 | 55,500 | 44 |

| Missouri | 1821 | 10,000 | 58,200 | 48,200 | 582 |

| Expanded South | |||||

| Tennessee | 1796 | 80,100 | 183,100 | 103,000 | 128 |

| Louisiana | 1812 | 69,100 | 168,400 | 99,300 | 144 |

| Mississippi | 1817 | 32,800 | 195,200 | 162,400 | 595 |

| Alabama | 1819 | 47,400 | 253,500 | 206,100 | 535 |

| Arkansas | 1836 | 0 | 19,900 | 19,900 | +++ |

The Armfield Slave Coffle Of 1834

The task of rounding up excess slaves in Virginia and other eastern states and transporting them west and south for sale belongs to a small group of firms which accumulate vast wealth from their efforts.

One pioneer slave trading firm is Franklin & Armfield, headquartered as of 1828 in Alexandria, Virginia. Residing there is John Armfield, who is born in 1797 in North Carolina. His uncle and partner is Isaac Franklin, born in 1789 to a Tennessee planter, veteran of the War of 1812, astute investor, and owner of plantations of his own in Tennessee and Louisiana. Over time the two develop a transportation route for moving “herds” of slaves overland for some 650 miles from Alexandria to Nashville, then from there to river barges for another 500-700 mile journey toward auction houses in Natchez, Mississippi, and New Orleans.

One such transport – known as the “Armfield Coffle of 1834” – sets out with 300 slaves in August. A witness describes the sight as follows:

Armfield sat on his horse in front of the procession, armed with a gun and a whip. Other white men, similarly armed were arrayed behind him. They were guarding 200 men and boys lined up in twos, their wrists hand-cuffed together, a chain running the length of their hands. Behind the men another 100 women and children were tied with rope. Then came six or seven big wagons carrying food, infants, and suits of clothing reserved to display the negroes at auction.

A list of six children who made this particular journey survives:

Some Slave Children In The 1834 Coffle

| Name | Gender | Age | Height |

| Bill Keeling | Male | 11 | 4’5” |

| Elizabeth | Female | 10 | 4’1” |

| Monroe | Male | 12 | 4’7” |

| Lovey | Female | 10 | 3’10” |

| Robert | Male | 12 | 4’4” |

| Mary Fitchett | Female | 11 | 4’11” |

The “coffle” moves at about three miles an hour and 20 miles a day in the sweltering summer heat. It travels from Alexandria along a variety of trails beginning with the Great Wagon Road through the Shenandoah Valley. On September 6, it makes a risky 125 yard crossing of the New River, south of Roanoke to avoid a ferry toll. From there it moves west toward Knoxville and then to Gallatin, Tennessee, some 30 miles northeast of Nashville.

Once there, Amfield turns the “coffle” over to Isaac Franklin’s nephew, James, to complete the final legs of the trip. While records end at this point, the slaves are likely put on flatboats for a three day ride down the Cumberland River to the Ohio, and then one more day to connect with the Mississippi. After another two week voyage south, they will likely dock at Natchez for sale. A contemporary visitor to that city claims that…

There is no branch of trade in this part of the country more brisk and profitable than that of buying and selling negroes.

The terminal for Armfield’s Coffle of 1834 is probably Isaac Franklin’s auction house located at Forks of the Road, near the end of the Natchez Trace. It has removed to this remote site after Franklin is caught in 1833 burying slaves who have died of cholera, causing panic and reprisals by city officials.

Sales at the Forks site follow a ritual, with slaves dressed up in finery and first paraded en masse in front of potential bidders.

The men dressed in navy blue suits with shiny brass buttons…as they marched singly and by twos and threes in a circle…The women wore calico dresses and white aprons, with pink ribbons in their hair.

After this showing, they are grouped by age and size, within gender. Sales are determined by haggling, not by an auctioneer. Thus a prospective buyer will point to a prospect, who will follow them to a more private site for closer inspection. This typically involves undressing and standing naked while examination is made of teeth and backs, the latter in search of prior whip marks, signaling defiance. Slaves may also be asked to speak, sing or dance, and to describe what work and skills they possess.

The entire process is one of abject humiliation.

Some of the “Armfield Coffle” may have ended up in New Orleans, the biggest slave “market” in the country, with over fifty dealers in business. A white visitor expresses his discomfort at the wide open nature of the city:

You have to squeeze through a countless multitude of men, women and children of all ages, tongues and colors of the earth until you get into the city proper. (The people) are made of the worst portion of the human race. No wonder that there should be robberies and assassinations in such a population.

The actual auctions are often seen as social events, with gawkers outnumbering bidders. Advertisements in local papers boast of “Virginia bred” slaves (meaning compliant) and “fancy girls” (sex slaves) who often go for top dollar. A diary records one such sale of a woman named Hermina:

On the block was one of the most beautiful women I ever saw…She was sold for $1250 to one of the most lecherous looking old brutes I ever set eyes on.

The “Armfield Coffle of 1834” is, of course, only one incident in an “industry” that thrives, as prospective plantation owners move west. In total, it’s estimated that over a half million American born enslaved persons are sold over the years in New Orleans. Among the results are shattered families, and heart-rending “seeking notices” that follow after the end of the Civil War. One example from a Mary Haynes, living in Texas:

I wish to inquire after my relatives whom I left in Virginia about twenty-five years ago. My mother’s name was Matilda. My name was Mary. I was nine years old when I was sold to a trader named Walker, who carried us to North Carolina. My younger sister Bettie was sold to a man named Reed, and I was sold and carried to New Orleans and from there to Texas. I had a brother, Sam, and a sister, Annie, who were left with mother. If they are alive, I will be glad to hear from them.