Section #12 - Southerners are alarmed by an apparent Northern wish to ban all blacks from the new West

Chapter 142: Salmon Chase’s New “Free Soil Party” Portends America’s “Third Political System”

1846 – 1848

Chase Spots A New Path To Defeating The Democrats And Ending Slavery

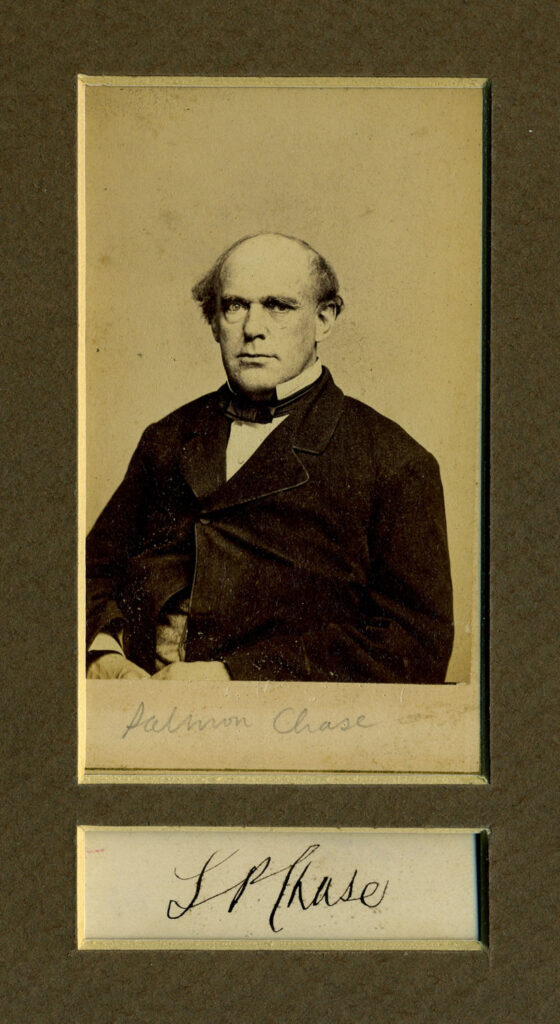

Emerging from all this political turmoil comes the figure of Salmon Portland Chase, the Cincinnati lawyer and abolitionist who helps found the Liberty Party in 1840 and now sees the opportunity to simultaneously defeat the Democrats, launch his own political career and end slavery.

Chase recognizes that while abolition will require political action, the vast majority of Americans regard blacks as both inferior and menacing, have little interest in their freedom, and are adverse to the prospect of assimilating them into white society.

The weak voting record for the Liberty Party (only 2% in 1844) also proves to him that abolition is not a stand-alone issue capable of garnering widespread popular support – especially if the outcome is perceived to disrupt the Union.

Those who hope to end slavery must therefore attach themselves to a “larger idea,” one having broad national appeal.

He spots this opportunity in 1846, when a majority in the House vote in favor of the Wilmot Proviso.

For Chase, the Proviso signals widespread public support for a new Manifest Destiny vision of America to the west – one that offers a chance to start over and eliminate all prior barriers to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” for white citizens.

Better yet for Chase the abolitionist, the key barrier in Wilmot’s sights is plantation slavery.

The House vote signals that plantation slavery must be banned in the Mexican Cession territories for free white men to realize the American Dream.

Such a ban will help the western settlers – sure to begin as farmers – succeed economically. It will eliminate the chance for wealthy plantation owners to outbid them for the best parcels of land, and, because of slave labor, to undercut the prices they can charge for their crops.

Moreover the Wilmot backers argue that the absence of all black slaves and their masters will have a profound positive effect on the quality of the white society that develops in the west.

For one thing, white settlers will be relieved of the perpetual fear associated with slave uprisings.

They will also avoid the decadent two-tiered social structure Northerners have come to associate with the South –with “one class of citizens accustomed to rule and the other to obey.”

Herein lies the “larger idea” that Chase has been after in his political quest. Ironically it offers a way to build broad opposition to slavery not by focusing on the suffering it causes the Africans, but rather on its negative impact on the hopes and prospects of the white population!

To convert these insights into action, however, will require a series of clever moves to bring all of the dissidents – from the Barnburners to the Conscience Whigs, the Abolitionist wings and the Wilmot supporters – together in one new national party.

Chase begins this task soon after the Wilmot vote by seeking consensus among those in the anti-slavery movement, men like Charles Sumner, Joshua Giddings, Preston King, and Charles Francis Adams. From there he begins to reach out to the Van Buren Loyalists and those touting “free soil for free white labor.”

August 9, 1848

A Free Soil Party Platform Is Passed

Chase’s efforts bear fruit on August 9-10, 1848, when upwards of 20,000 supporters from 17 states pour into the city of Buffalo to give birth to The Free Soil Party.

The tenor of the August 9-10 convention is reminiscent of the revivalist meetings that swept America in the 1830’s. It is held in the open air Tent In The Park and features a series of charismatic speakers who attempt to resurrect the spirit of 1776 and enlist their audience in the crusade against the spread of plantation slavery.

The proceedings are widely reported, thanks to one Oliver Dyer, a 24 year old expert in shorthand, who provides a “phonographic record” of the events to newspapers across the country.

By nine o’clock the concourse was immense. Every available seat and foothold on the ground was occupied. The Ohio delegation came into the tent with banners flying and were received with great cheering…and exhortations and expressions of determination to ‘put the thing through, no giving up, no compromises, free soil and nothing else.’

Mr. Polk of Connecticut offers this sentiment: ‘let men of the deepest principle, manifest the most profound condescension, and exercise the deepest humility today, and posterity will honor them for the deed.’

Chase is assigned the task of preparing a platform centered on Wilmot’s ban of slavery in the west – without offering “justifications” that could prove divisive. The result is a sixteen point platform which sets the Free Soil Party in stark contrast to the wishes of the Slave Power.

1. We do plant ourselves upon the national platform of freedom in opposition to the sectional platform of slavery.

2. That slavery…depends upon state law which cannot be repealed or modified by the federal government.

3. That the provisos of Jefferson…clearly show that it was the settled policy of the nation not to extend, nationalize or encourage, but to limit, localize and discourage slavery…and to this policy the government ought to return.

4. That our fathers…denied to the federal government a constitutional power to deprive any person of life, liberty or property, without due legal process.

5. That Congress has no more power to make a slave than to make a king; no more power to establish slavery than to establish a monarchy.

6. That it is the duty of the federal government to relieve itself of all responsibility for the existence or continuance of slavery.

7. That the only safe means of preventing the extension of slavery…is to prohibit its extension in all Territories by an act of Congress.

8. That our calm but final answer to the slave power is no more slave states or slave territories. let the soil of our domain be kept free for the hardy pioneers of our land and the oppressed and banished of other lands seeking homes of comfort in the new world.

9. That the committee of eight bill in the Senate (proposing extension of the 36’30” MO line) was no compromise but an absolute surrender of non-slaveholders…by several senators… who voted in open violation of the will of their constituents. There must be no more compromises with slavery; if made they must be repealed.

10. That we demand freedom and established institutions for our brethren in Oregon now exposed to hardships by the reckless hostility of the slave power to the establishment of free government for free territories.

11-15. That we support…cheap postage, a retrenchment of federal patronage, river and harbor improvements as needed, the free grant to actual settlers of reasonable portions of public lands, the earliest practical payment of the national debt, a tariff of duties to defray the expenses of the federal government and pay annual installments against the debt and the interest thereon.

16. That we inscribe on our banner “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, And Free Men,” and under it we will fight on and fight forever until a triumphant victory shall reward our exertions.

The platform avoids the controversial themes associated with the abolitionists – moral condemnation of slaveholders; immediate emancipation of all slaves even in the South; assimilation of the ex-slaves into white society.

It focuses not on freeing the slaves from their misery, but on freeing white men from the diminishing effects of living with slavery in their midst.

As Walt Whitman, convention delegate and editor of The Brooklyn Eagle puts it:

The workingmen of the North, East and West, in defense of their rights, and their honor, declare that their calling shall not be sunk to the miserable level of Negro slaves.

The argument here is that the founders, including Jefferson, recognized that slavery threatens the dignity and supremacy of white America; they intended to limit, not expand it; and the time is now to carry out their wishes.

These sentiments fall short of what Chase and other abolitionists ideally hoped to achieve.

Upon reading the platform, Lloyd Garrison first calls it another example of “white-manism”– but then, upon further reflection, says that it signals “the beginning of the end” for the slave power, and vows to drive the movement “to a higher ground.”

Chase, the astute politician, sees it the same way. It is a first step, giving average Americans a middle ground they seek between the Slave Power’s insistence on spreading slavery and the abolitionist’s demand for immediate emancipation.

The “Free Soil” formula is simple: pen the slaves up in the old South; let those who support the institution deal with the problems; and wait for the institution to wither away.

August 10, 1848

The Free Soil Party Nominates Martin Van Buren

When the time comes for the convention to select a nominee both wings of the new party offer candidates.

The abolitionists rally around Senator John Hale of New Hampshire, who has earlier been chosen by The Liberty Party as its 1848 nominee. Along with Joshua Giddings of Ohio, Hale has led the drive in Congress against the Slave Power. He opposes the Texas Annexation and the Mexican War, and even stands along in opposing resolutions honoring Generals Taylor and Scott.

The final nod, however, goes to the Van Buren Loyalists and to those backing Wilmot on behalf of white settlers, not black slaves.

Their candidate is none other than Martin Van Buren himself, ready at sixty-six to reclaim his rightful place in the White House.

Free Soil Nomination Results

| Candidates | Votes |

| Van Buren | 244 |

| Hale | 183 |

| Giddings | 23 |

| Charles F. Adams | 13 |

| Others | 4 |

| Total | 467 |

The choice for Vice-President, by a unanimous vote, is Charles F. Adams, son of President JQ Adams and a noted Conscience Whig.

When the convention closes, the delegates exit Buffalo with great optimism.

They have a platform that offers western settlers a chance to prosper without the barriers of plantation slavery, and one that serves the end goals of the abolitionists. Their marching banner – “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor and Free Men” – rings true to their intent, and comes across as tempered, non-radical, and likely to resonate broadly in the North and West.

And they have a well-known nationally respected figure in Martin Van Buren at the top of their ticket.

This may or may not be enough to contend with the Democrats and the Whigs, but at least it represents a solid start in that direction.

While the Free Soilers will not prevail in 1848, it will open the door to the “Third Party System” in America vis its 1856 offspring, the Republicans.