Section #20 - Futile attempts to save the Union follow John Brown’s Raid at Harpers Ferry

Chapter 242: Respect For John Brown Grows From His Capture To His Execution

October 18, 1859

The Captive’s Bearing Surprises The Southerners

John Brown’s behavior and words between the time he is captured on October 18, 1859 and the time he is hanged on December 2 have much to do with changes in the way he is perceived by the public at large in the North.

Newspaper reporters pour into Harpers Ferry from along the east coast by the time he is taken. So too do various politicians, eager to pepper him with questions about the raid. A three hour grilling is completed while he is still prone in the Armory. Virginia congressman Alexander Botelier asks if Brown if he “expected to get assistance here from whites as well as blacks?”

I did, and yes, I have been disappointed.

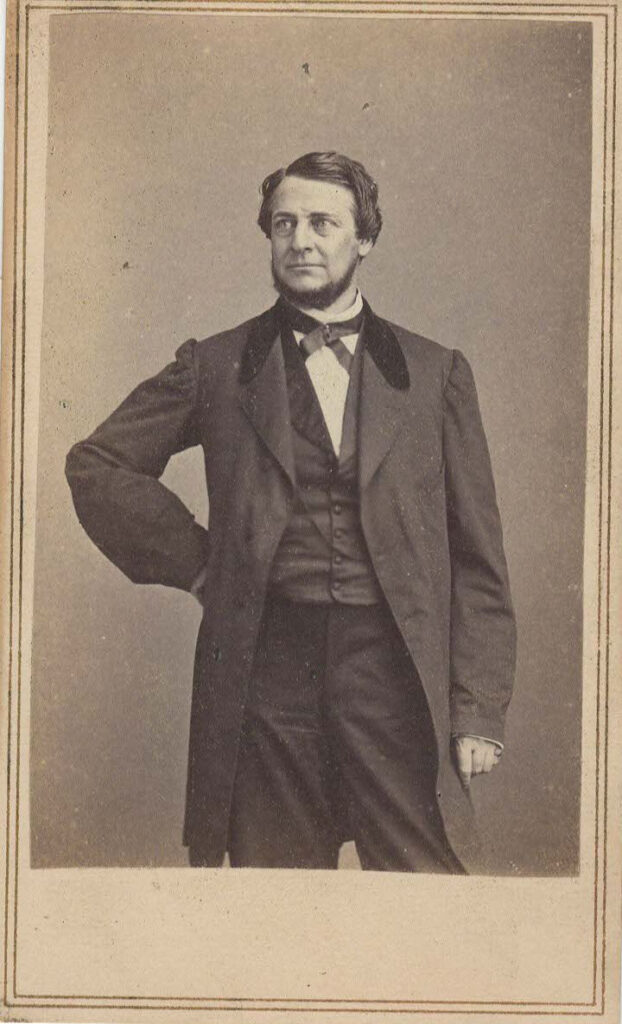

Two other Virginians, Senator James Mason and Governor Henry Wise, are joined by the pro Southern Ohio Governor Clement Vallandingham in a series of questions:

Q: Who funded you?

A: I cannot implicate others.

Q. Mr. Brown, who sent you here?

A. It was my own prompting and that of my Maker.

Q. What about the loss of innocent lives?

A. If there was any killing of innocent people, it was without my knowledge.

Q. Did you consider this a religious service?

A. It was the greatest service man can render to God.

Q. Do you consider yourself an instrument in the hands of God?

A. I do.

Brown ends this initial interrogation with the first of many words that will appear in newspaper and other written accounts over time:

I wish to say, furthermore, that you had better – all you people of the South –prepare yourselves for a settlement of this question. You may dispose of me very easily…but not the negro question. The end of that is not yet.

Those expecting to hear the rantings of a lunatic abolitionist are thrown by Brown’s demeanor and responses. When asked to characterize his prisoner, Governor Wise replies:

They are themselves mistaken who take him to be a mad man. He is a man of clear head, of courage, fortitude and simple ingenuousness. He was humane to his prisoners…(also) vain and garrulous, but firm, truthful and intelligent.

Vallandingham is also surprised by Brown:

Captain John Brown is as brave and resolute a man as ever headed an insurrection….He is the farthest possible remove from an ordinary ruffian, fanatic or mad man. Certainly his was one of the best planned and best executed conspiracies that ever failed.

While both men will soon regret these initial remarks, they do reflect a certain grudging admiration for Brown’s code of conduct, which seems in many ways to mirror the Southern ideal. He commits himself to fighting for his cause. His plan of attack is bold and meticulous and well executed, albeit to the chagrin of his opponents. He exhibits great personal courage during the battle, surrendering only after being severely wounded. He protects his hostages from harm. His responses when captured are forthright and his manner is that of a gentleman. He shuns excuses and awaits his fate with dignity.

He may be Osawatomie Brown of Kansas fame, but Governor Wise and other who now encounter him find that his bearing and words resonate with many of the courtly traditions of the South.

November 2, 1859

Brown Is Tried And Sentenced To Death

Brown’s demeanor, however, does nothing to delay the cry for swift retribution in the South. Together with the four others in custody, he is transferred to Charles Town, the seat of government for Jefferson County, located seven miles to the west of Harpers Ferry.

The intent of his captors is try Brown first, and then move on later to his associates. With that in mind, the wounded warrior is formally indicted on October 25, 1859, one week after the raid. The charges include treason against Virginia, inciting slaves to violence, and murder. In the interim, arrangement are made for a trial and lawyers are chosen to defend him. He responds with dismissiveness:

If I am to have nothing but a mockery of a trial…I do not care anything about counsel. It is unnecessary to trouble any gentlemen with that duty.

His wishes are ignored and the trial begins the following day in a courtroom packed with some 500 spectators, many smoking cigars, consuming roasted peanuts and contributing shouted curses as they deem appropriate.

Judge Richard Parker, a former US congressman, presides, and Brown is initially defended by two southern lawyers who encourage him to plead “hereditary insanity” to escape a death sentence. Brown brushes away this idea before two northern lawyers arrive for his defense. Judge Parker rejects their plea for a delay, and they plunge forward arguing that his mission was humanitarian in nature, the slaves did not riot, all hostages were treated with respect and were unharmed, and that the deaths were not premeditated but the result of combat.

Furthermore, since their client was not a citizen of Virginia, he could not be guilty of treason against the state.

Closing statements from both sides occur on October 31 and the jury is dismissed to deliberate. They do so for forty-five minutes before returning a verdict of guilty on all counts.

Sentencing occurs on November 2, before which Judge Parker offers Brown the chance to address the court, and he does so with words and demeanor that, once publicized, cause observers on both sides to re-think their beliefs about his sanity and his actions…

I have, may it please the court, a few words to say…

I deny everything but what I have admitted all along…a design on my part to free the slaves…I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.

I believe that to have interfered as I have done…in behalf of His despised poor, I have done no wrong, but right.

Now if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel and unjust enactments, I say, let it be done.

Like Governor Wise, some Southerners who are present are moved by the dignity and eloquence of this address.

But words alone are hardly enough to dismiss the profound sense of community and sectional terror created by the raid – and Parker sentences Brown to death by hanging, one month hence.

Hearing the news, Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator tells its readers to…

Let the day of his execution…be the occasion of such a public moral demonstration against the bloody and merciless slave system as the land has never witnessed.

November 3 To December 1, 1859

America Learns About Captain Brown While He Is In Prison

During the twenty-nine days that follow his sentencing, John Brown does nothing but enhance the impression he makes on his captors, and on the outside world.

A reporter who interviews him remarks on his Calvinist convictions:

Captain Brown appears perfectly fearless in all respects. Says that he has no feeling about death on a scaffold and believes that every act, even all follies that lead to disaster, were decreed to happen ages before the world was made.

His own correspondence reinforces his belief that freeing the slaves was his God-given destiny, and that goodness will come from his actions.

I feel quite cheerful in the assurance that God reigns & will overrule all for His glory & the best possible good.

He also reflects on the past, especially to his time in Kansas, and his role in the Pottawatomie Massacre. On this count, he seems to give himself the benefit of the doubt:

I never shed blood of my fellow man except in self-defense or in promotion of a righteous cause.

As the end draws near, he recognizes that his final contribution to his cause will come on the scaffold. He writes as much to his half-brother, Jeremiah:

I am worth inconceivable more to hang that for any other purpose. …I have fought the good fight and have finished my course.

His concerns are for the future well-being of his family. He admonishes them to study the Bible and to abhor slavery. He pleads with his wife to stay home to avoid the emotional turmoil of his execution and to conserve their money. He asks that a handful of slaves accompany him to the gallows and that his body be burned along with his two dead sons, Watson and Oliver.

Mary Ann Brown, his wife of 26 years and mother of 13 of his 20 children, ignores his pleas and arrives on the day before he is executed. She spends four hours with him, but is convinced to not witness his death. His request that she be allowed to stay with him through the night is denied.

December 2, 1859

The Execution Is Carried Out

I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood. I had…vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.

Crowds gather to get a final glimpse of the prisoner, but few succeed, since a hyper cautious Governor Wise floods the town and the surrounding roads with troops to prevent any possibility of a last second rescue. Some 3,000 armed guards are present, comprising local militias and 264 federal troops, again under Robert E. Lee.

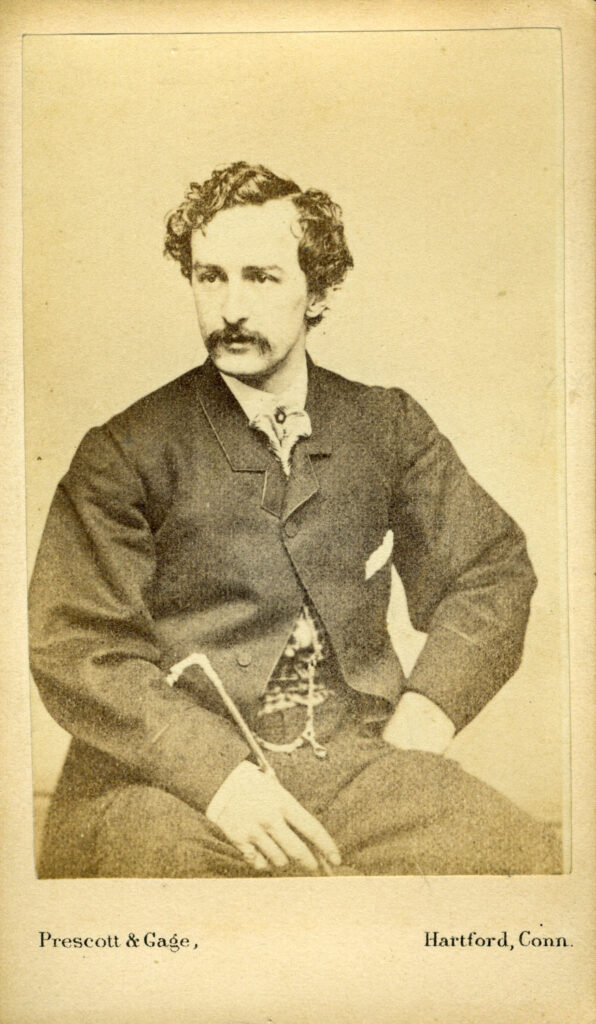

The execution site is also cordoned off from the public, except for a few who manage to slip through. Among them are John Wilkes Booth posing as a militia member, and the prominent fire-eater, Edmund Ruffin, who already intends to build his case for Southern secession around the Harpers Ferry incident.

The scaffold is freshly built for the occasion. The platform is 12’ by 16’ and six feet high, reached by twelve stairs. At the front is a crossbeam with a short noose hovering over a trap door. Brown arrives along with his coffin and an undertaker named Sadler who tells him:

You’re the gamest man I ever saw, Captain Brown.

Brown replies:

I was so trained up; it was one of the lessons of my mother; but it is hard to part from friends.

He has refused the offer of a clergyman, so climbs the stairs and moves to the trapdoor on his own. Observers comment on his dignified manner and unwavering courage. His hat is removed, and a white linen hood is fitted over his face. His only request is that the sentence be carried out without ceremony and quickly. But he is forced to stand still for almost ten minutes as mounted troops are brought into place.

When the trap-door is sprung, his drop is only two feet, but fortunately it is enough to snap the spinal cord in his neck, and he dies quickly. After another thirty-five minutes his body is cut down and placed in his coffin.

Colonel Preston issues the final official word at the scene:

So perish all such enemies of Virginia and of the Union and of the human race.

Wilkes Booth records a different coda in his diary:

He was a brave Old Man.

December 3-7, 1859

John Brown’s Body Lies A Mouldering In His Grave

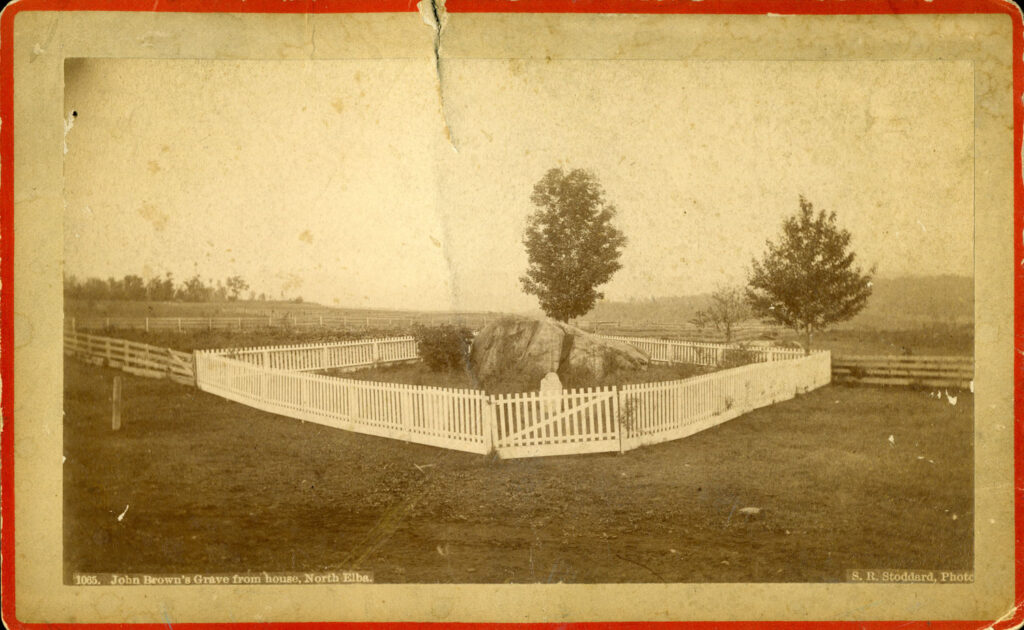

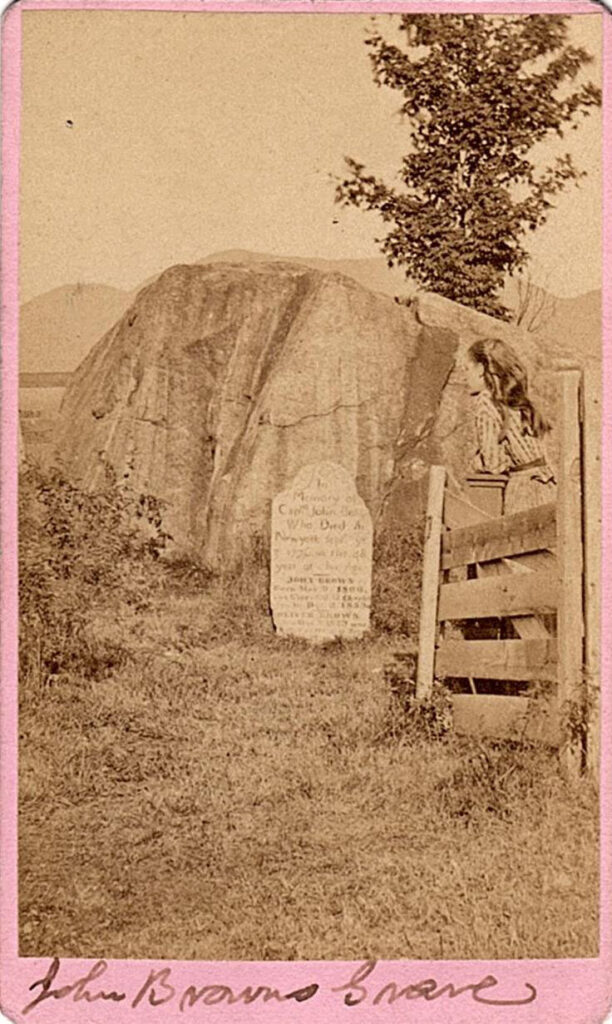

On December 3, Mary Ann Brown begins a five day journey with her husband’s corpse, by train to Philadelphia and boat to New York, followed by a 25 mile trek overland to the farm in North Elba, NY.

She wishes to take her two dead sons along, but Brown’s request has been denied. Watson’s body is handed over to the Winchester Medical School for anatomical research, while Oliver’s remains, along seven others are thrown into two crude pine boxes and buried alongside the Shenandoah River. (By 1899 the remains of the two sons, along with nine other raiders will be acquired and reburied next to Brown.)

A small and simple memorial service follow on December 7. His body is transferred to a new casket by his family, and it is left open while his neighbors and other friends file past.

He is then lowered into a nearby grave next to a huge bolder where he has carved his name in case he should die at Harpers Ferry. His headstone – moved years before from Connecticut to the farm — is that of his grandfather, Captain John Brown, who lost his life fighting in the American Revolution. Brown’s name, along with those of Oliver and Watson, are added below the original inscription.

The ceremony itself is simple and brief. It is marked by the singing of his favorite inspirational hymn:

Blow ye the trumpet, blow.

The gladly solemn sound;

Let all the nations know,

To earth’s remotest bound,

The year of Jubilee has come.

Final tributes are spoken by several attendees, including Wendell Phillips:

Marvelous old man! He has abolished slavery in Virginia…History will date Virginia Emancipation from Harpers Ferry. His words, they are even stronger than his rifles. They crushed a State. They have changed the thoughts of millions, and will yet crush slavery.

John Brown’s story would seem to be over – but it is hardly over.