Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

Chapter 120: Polk Gets His Tariff Bill Approved

1828-1845

Tariff Rates Continue To Cause North-South Friction

For the hard-charging President Polk, the first three months in office have been a whirlwind, although he remains determined to complete all his identified objectives in one term.

He has settled the border dispute over Oregon on June 18, 1846, and his forays into Texas and Alta California are progressing well. He decides now to tackle nagging issues related to tariffs.

Polk was a second term member of the U.S. House in 1828 when the “Tariff of Abominations” bill – cynically designed to undermine the South’s political opponents – backfired on John C. Calhoun, and was signed into law. It doubled the tax on imported goods to an average of 45%.

For the nascent New England manufacturers, this high tariff on imported goods such as cotton, wool and pig iron provides marketplace “protection” by keeping their retail prices in line with what is offered by their competition – the larger and hence more efficiently run factories in Europe.

The West also favors the higher rates, since they stand to benefit disproportionately from increases in the government’s infrastructure spending that will follow.

Federal Spending On Internal Improvements (1820-29)

| Region | % Spending | % Population |

| North | 49% | 47% |

| South | 19 | 40 |

| West | 32 | 13 |

Meanwhile the Southern planters are outraged by the negative effects on the tariff on their cotton industry. This leads to the attempt by South Carolina to “nullify” the law and Jackson’s “Force Bill” threating to send in troops to insure compliance.

Jackson lowers the rates in 1830, only to have the “protectionists” drive them back up in 1832.

The Compromise of 1833 delivers a framework that holds up well until 1842. It focuses on all imported goods currently being taxed at high rates in 1833 and imposes a formula for gradual yearly reductions to adjust them down to a 20% target by 1842.

But when 1842 arrives, the Whigs have taken control in Congress, and, despite two vetoes by Tyler, Henry Clay’s so-called “Black Tariff” drives the levies back up to roughly 40%.

July 28, 1846

Congress Passes The “Walker Tariff Of 1846”

As a congressman, Polk experiences all of this regional turmoil and hopes to never see it repeated.

He believes – with good cause – that America’s manufacturing sector is now well established, and no longer in need of “protection” from the federal government. At the same time, however, he recognizes that tariff revenues continue to supply upwards of two-thirds of all money coming into DC. These funds will now be needed to carry on the Mexican War, in addition to further infrastructure projects.

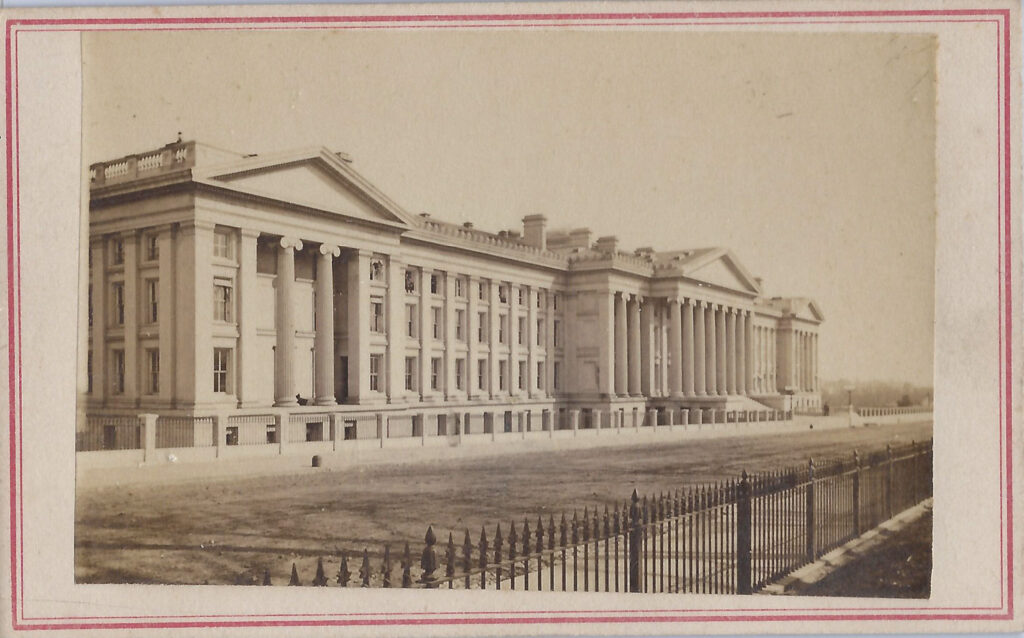

Polk charges his Treasury Secretary, Robert Walker, with arriving at a new tariff bill that lowers the tariff while striking a proper balance between the financial needs of the nation and the political needs of his Democrat party.

The “Walker Tariff of 1846” breaks imported goods into five classes, assigning staggered rate to each, from a high of 100% to a low on 0%, reserved for coffee and tea. The historically most fought-over items fall into the “C-Class” (iron, other metals, wood, glass, paper, wool, woolens, leather) taxed at 30%, and the “D-Class” (including cotton) at 25%.

The Bill breezes through the House but ends in a tie 27-yea vs. 27-nay vote in the Senate – and only due to a last ditch effort by the Governor of Tennessee to convince Whig Senator Spencer Jarnigan to vote “yes.”

Responsibility for breaking the tie falls on the shoulders of Polk’s Vice-President, George Dallas, of Pennsylvania. Dallas plans to run for President in 1850 and knows that his backing in New England will erode if he supports the lower tariff. Still, as a Democrat, he has no real choice in the matter. He votes “aye” on July 28, 1846, and the Walker Tariff becomes the law of the land. It will survive intact until 1857 when rates are further reduced to 17% on average.