Section #5 - A new Whig Party favors industrialization over the Democrat’s agrarian economy

Chapter 48: Political Fault Lines Over Geography And Slavery Are Amplified In The 1824 Presidential Race

1822

The Democratic-Republicans Split Into Three Factions In The 1822 Congressional Election

By the mid-terms of 1822, it’s clear that the “Virginia Dynasty” of Jefferson to Madison to Monroe will come to an end in the upcoming presidential race. So too will the smooth political harmony enjoyed by the Democratic-Republicans over the last twenty-four years.

Three factions within the party emerge at once: one backing Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams; a second favoring Treasury Secretary, William Crawford; and a third committed to General Andrew Jackson.

The mid-term election in 1822 tests the relative strengths of the presidential contenders.

The results in both the House and the Senate demonstrate that, as of December 1822, no one man enjoys the majority position needed to win the prize.

1822 House Election

| Winners Who Support | Total | South | Border | North | West |

| JQ Adams | 87 | 4 | 14 | 58 | 11 |

| Andrew Jackson | 71 | 26 | 7 | 33 | 5 |

| William Crawford | 55 | 37 | 2 | 14 | 2 |

| 213 | 67 | 23 | 105 | 18 |

Spring 1824

Five Candidates Vie For The Presidency In 1824

By 1824, the absence of a clear front-runner expands the list to five contenders.

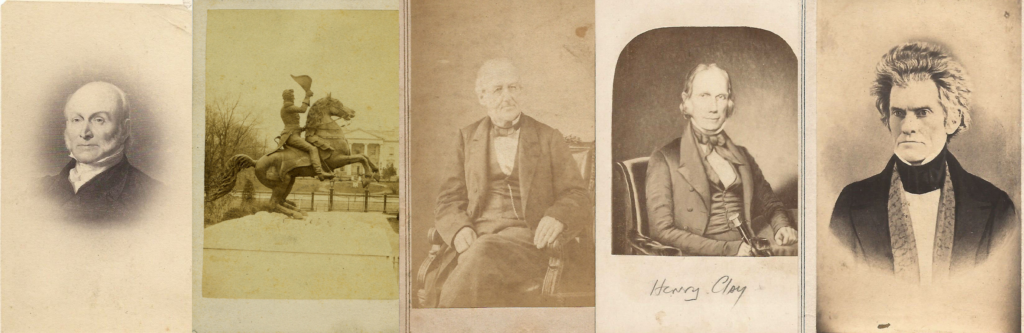

The most obvious successor to Monroe is John Quincy Adams, 55 years old, son of an ex President, serving in government for over three decades, and supremely qualified after working alongside Monroe for eight years as Secretary of State.

The problem with Adams is his personality, or lack thereof.

He is in the mold of the old-time Puritans, hard-working to an extreme, prone to signaling superior moral rectitude, stern and mostly humorless. All admire his talents and accomplishments; few count him a close friend. His political strength is centered in New England, especially his home state of Massachusetts.

Monroe’s Treasury Secretary, William Crawford of Georgia, enjoys support from two critical centers of electoral gravity – the Virginian trio of Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, and the so called “Albany Regency” in New York. The latter is controlled by Martin Van Buren, a political mover and shaker from age seventeen onward, and serving since 1821 in the U.S. Senate. His “city hall machine,” is built on patronage, and can be counted on to deliver the bulk of New York’s electors. Van Buren lines these up behind Crawford.

Adams and Crawford are joined in the race by two other powerful Washington men — Secretary of War, John Calhoun, and House Speaker, Henry Clay.

Calhoun is respected for his brilliant intellect, but, along with Adams, is seldom well-liked at the personal level. Many regard his demeanor as unpleasantly messianic, as if he alone were capable of discerning what is right for the country, while being held back by lesser men around him. His overt ambitiousness leads to questions about his motivations and trustworthiness, and Northerners suspect that his agenda is skewed toward southern rather than national interests.

Unlike Calhoun and Adams, Henry Clay is a comfortable figure, ever ready to drink and gamble and party with his fellow politicians, and flexible about meeting them half way on most contentious issues. He also comes with a “platform” of sorts, in the form of what he calls his “American System” of government, focused on accelerating economic growth through federally funded infrastructure initiatives, a protective tariff and a strong central bank. According to his supporters, Clay is a symbol of America’s future – born in the east (Virginia), venturing to the west (Kentucky), linking the old with the new in search of a strong, enduring Union.

The fifth contender for president, Andrew Jackson, differs from the others. He is a military man rather than a politician — but also a national hero, first for his stunning defeat of the British in 1815 at New Orleans, and more recently for various victories over Indian tribes in Georgia and Florida. As an outsider to Washington, he is initially dismissed as a serious candidate until astute handlers in Tennessee get the state legislature to officially nominate him for the presidency in 1822, and then elect him to the Senate in 1823. From that point forward he bursts on the scene as the frontrunner, and the common target to be stopped by his four competitors.

Fall 1824

JQ Adams And Andrew Jackson Emerge As Favorites

Jackson’s sustained popularity convinces the party pro’s that no candidate will be capable of securing an electoral vote majority in December 1824, and that it will ultimately be up to the House to choose Monroe’s successor.

According to established rules, the top three vote-getters in the general election, will be eligible for a run-off. This sends each candidate in search of locking in states they hope to win in the first round and then individual House members who might tip the balance in the follow-up.

Amidst this scramble, the electoral math shifts dramatically in September of 1823, when William Crawford, favored by the Virginians and Van Buren, becomes ill and is given an overdose of digitalis, a powerful drug that leads on to a massive stroke. He is left partially paralyzed, nearly blind, and unable to speak, with none knowing if the condition is temporary or permanent. On the hope that he will recover, his condition is kept largely secret throughout the campaign.

Despite his health, Van Buren tries to force the issue in Crawford’s favor through a traditional nominating caucus of congressional members, held on February 24, 1824. But only 66 of the 216 members show up, sharply reducing the impact of the Crawford-Gallatin ticket chosen.

Meanwhile Calhoun’s chances vanish when his one hope for northern support, Pennsylvania, declares in favor of Jackson, and Clay is attacked for leading a libertine lifestyle and for promoting programs that sound more like the Federalists than like Jefferson.

Characteristically, JQ Adams, who very much wants the presidency, finds it beneath his sense of dignity to campaign for it in any fashion.

1824 Forward

Sectional Issues Begin To Reshape The Political Landscape

The election of 1824 also amplifies two emerging political factors.

One relates to geography.

Over two million Americans, one in every four, already reside west of the Appalachian Mountains, and their number is growing rapidly. The daily lives of these frontier families differ from those in the “settled East,” as do some of their wishes and expectation for the national government. The 1824 race represents a chance for their voices to be amplified.

The second factor beginning to divide the electorate involves tension over the long-term fate of the black population.

As demonstrated by the conflict surrounding the 1819 Tallmadge Amendment, Southerners are committed to expanding slavery into the western territories, while Northerners want to banish all blacks, enslaved or free.

Taken together, the one nation harmony of 1820, is challenged in 1824 along two regional fault lines: East vs. West and North vs. South.

Political Fault Lines Emerging In 1824

| Geography | Slavery Allowed (12) | Slavery Banned (12) |

| Old Established East Coast States (15) | Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, N Carolina, S. Carolina, Georgia | Mass/ Maine, NH, Vermont, Conn., Pa, RI, NY, NJ |

| Emerging States West Of Appalachia (9) | Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Missouri | Ohio, Indiana, Illinois |

Voting power within these four cells differs dramatically, and is a key determinant in choosing a president. The lion’s share (106 in total) of the Electoral Votes remains in the northeastern states, with Pennsylvania (29) and New York (28) particularly important. States where slavery is banned, and blacks are unwelcome, also enjoy a 129-113 edge.

Voting Power In 1824: # Of Seats In Congress

| Slavery Allowed (12) | Slavery Banned (12) | Total | |

| Old East Coast States (15) | 73 | 106 | 179 |

| Emerging States West (9) | 40 | 23 | 63 |

| Total | 113 | 129 | 242 |

Once Calhoun drops out in favor of seeking the vice-presidency, four contenders remain.

JQ Adams, as the lone representative of the northeast, begins with a solid base, despite his shift in 1808 from his father’s Federalist Party to the Democratic-Republican side.

Crawford’s original strength in the old South and, via Van Buren, in New York, is formidable, but weakening as word of his uncertain health spreads. (Miraculously, he eventually recovers some of his faculties and lives until 1834.)

Then come the two “men of the West” who have already come to detesting each other: Clay, the Washington political infighter for over a decade; and Jackson, the military man and outsider.