Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

Chapter 134: Political Battles Intensify Over A Proper Peace Treaty With Mexico

Winter-Spring 1847

Disputes Exist Over Terms For Peace

By the winter of 1847, Polk realized that winning the war with Mexico has not ended the political battles surrounding the original annexation of Texas and the Wilmot Proviso ban on slavery in land acquired by the conflict.

Even within his own Democratic Party, divisions run deep about what to do with Mexico and its territory.

Polk’s Treasury Secretary, Robert Walker, wants to annex the entire country.

James Buchanan, who publicly opposed any land acquisition when the war began, now turns acquisitive, to boost his odds for the presidential nomination. Once again Polk is enraged by his erratic Secretary of State.

Senator John C. Calhoun, whose hawkishness over Texas provoked the war, expresses horror at this thought – which would blemish America’s racial purity.

We have never dreamt of incorporating into our Union any but the Caucasian race – the free white race. To incorporate Mexico, would be the very first instance of (including) an Indian race. Ours, sir, is the government of the white man…To erect these Mexicans into a territorial government and place them on an equality with the people of the United States is (something) I protest.

Then there is the especially galling New York wing of the party, now being called the “Wilmot Proviso Democrats,” who continue to insist on the slavery ban.

Polk himself opposes a wholesale annexation, but argues that America must be “indemnified” (i.e. compensated) for the costs of a war Mexico started by “their invading U.S. soil” along the Rio Grande on April 25, 1846. He decides to “wait out” the Mexicans, hoping they will offer up attractive peace terms.

He has sent his version of the territorial boundaries he favors to Nicholas Trist of the State Department, to advance talks toward a treaty.

But gradually he learns that Trist is negotiating on his own terms, with potential concessions in Texas and Alta (upper) California that Polk opposes. He also hears that Scott has court-marshaled his confidante, Pillow, and joined Trist in working out a treaty, including a possible $1 million bribe to Santa Anna.

At this point, Polk concludes that the time has come to sack both Trist and Scott — but he is emotionally so averse to personal confrontations that both men stay on by default.

Feb 12, 1848

The Whig, Abraham Lincoln, Calls The War A “Sheer Deception”

Polk’s troubles from his Democrats are now matched by an increasingly vocal Whig opposition, with its 116-112 majority in the House.

On November 13, 1847, Henry Clay lays out the Whig position in a speech in Lexington, Kentucky. The war was one of “aggression,” not defense, initiated by Polk’s false claim that Mexico invaded U.S. land. The end must not lie in annexing all of Mexico or in any extension of slavery into new land. Hearing these words, Polk’s supporters label Clay a convert to the abolitionist movement.

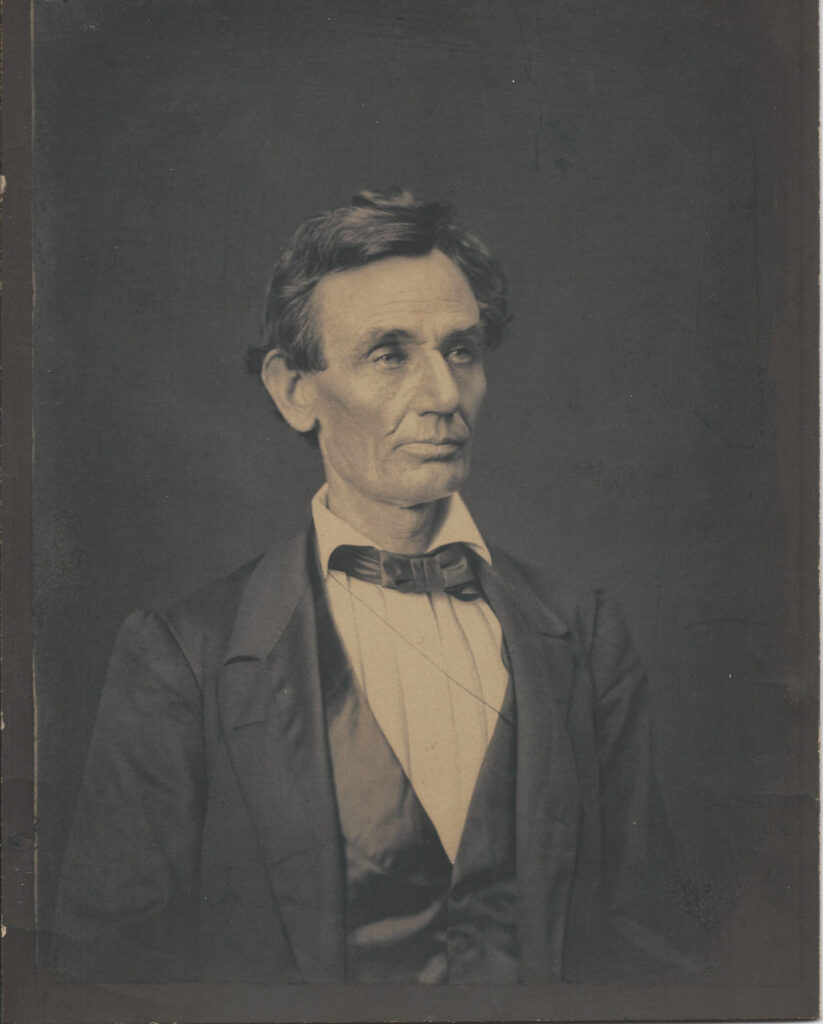

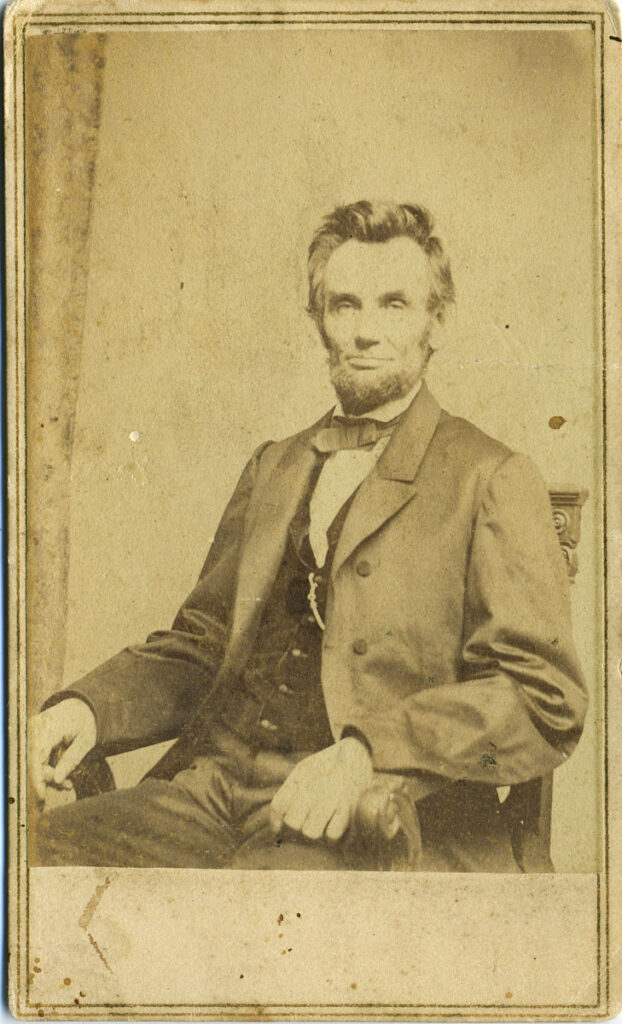

As the second session of the 30th Congress convenes, Clay’s arguments are amplified in two addresses by the 38 year old freshman representative from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln.

Since speaking out after the 1837 murder of the abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy, Lincoln has devoted his energy to building a law practice in Springfield, courting and marrying Mary Todd in 1842, buying a home, and raising his first two sons, Robert and Willie. He has also dabbled in local politics, serving four terms in the Illinois House. In 1846, he is elected to the US House as the only Whig in a delegation dominated by Douglas and his Democrats.

Lincoln’s reputation is that of a “free soil man,” opposing those who would seek to extend slavery geographically, while not calling for abolishing it entirely. As such he will vote five times in favor of Wilmot’s proviso during his term in office.

His first address to the House, on December 22, 1847, is very brief but pointed. It becomes known as the “spot speech” for its “respectful request” of the President to inform the members…

1st. Whether the spot on which the blood of our citizens was shed, as his messages declared, was or was not within the territory of Spain, at least after the treaty of 1819, until the Mexican revolution.

2d. Whether that spot is or is not within the territory which was wrested from Spain by the revolutionary Government of Mexico.

3d. Whether that spot is or is not within a settlement of people, which has existed ever since long before the Texas revolution, and until its inhabitants fled before the approach of the United States army.

After eight such constructions, Lincoln made the case that America was intruding on Mexican land, and not vice versa when the fighting began.

Lincoln’s second speech comes nine days after the House passed a resolution by a vote of 85-81 saying that the war was “unnecessarily and unconstitutionally begun by the President of the United States.” It paints a picture of a President who deceived the nation into starting a war to grab land belonging to Mexico, and is now “bewildered” about how to force the Mexicans into a treaty that makes it all look legal.

Mr. Chairman: Some if not all the gentlemen on the other side of the House… have spoken complainingly …of the vote given a week or ten days ago declaring that the war with Mexico was unnecessarily and unconstitutionally commenced by the President… I am one of those who joined in that vote; and I did so under my best impression of the truth of the case.

The President, in his first war message of May, 1846, declares that the soil was ours on which hostilities were commenced by Mexico… Now, I propose to try to show that the whole of this issue and evidence is from beginning to end the sheerest deception.

All of this is but naked claim; and what I have already said about claims is strictly applicable to this. If I should claim your land by word of mouth, that certainly would not make it mine.

I am now through the whole of the President’s evidence… (and) I more than suspect already that he is deeply conscious of being in the wrong.

My way of living leads me to be about the courts of justice; and there I have sometimes seen a good lawyer, struggling for his client’s neck in a desperate case, employing every artifice to work round, befog, and cover up with many words some point arising in the case which he dared not admit and yet could not deny and from just such necessity, is the President’s struggle in this case.

He insists that the separate national existence of Mexico shall be maintained; but he does not tell us how this can be done, after we shall have taken all her territory…As to the mode of terminating the war and securing peace, the President is equally wandering and indefinite.

As I have before said, he knows not where he is. He is a bewildered, confounded, and miserably perplexed man. God grant he may be able to show there is not something about his conscience more painful than his mental perplexity.

A decade later, Stephen Douglas will cite these speeches as evidence of Lincoln’s “lack of patriotism” when the two pair off in a race for a senate seat.