Section #5 - A new Whig Party favors industrialization over the Democrat’s agrarian economy

Chapter 47: Monroe Issues His “Hands Off The Americas” Doctrine

1819-1821

Spain Pressures Monroe Over Diplomatic Policies Related To Latin America

With the domestic conflicts over the admission of Missouri palliated, President Monroe and Secretary of State JQ Adams turn their attention to diplomatic concerns provoked by King Ferdinand VII of Spain.

Ferdinand has been kicked off his throne in 1808 and imprisoned in France for five years, while Napoleon’s brother, Joseph Bonaparte, rules the nation. He returns in 1813, after the French army is beaten back from Moscow, only to find that his once far reaching colonial empire much diminished in his absence.

Ferdinand is particularly distraught over lost revenues from his colonies in Latin America, where various “liberators” are at work, with the effects reaching all the way up to America’s southern neighbor, Mexico.

The Mexican independence movement begins in 1810 with the renegade priest, Miguel Hidalgo, whose peasant army wins several battles before being defeated in July 1811. After Hidalgo’s execution, leadership of the army falls on Jose Maria Morelos, who fights on, holds a conference declaring independence, but is ultimately defeated and killed in 1815.

Ferdinand is able to hold onto Mexico for seven more years before independence is finally achieved — ironically under the leadership of Colonel Augustin de Iturbide. This caudillo initially opposes the rebels, but then seizes on populist anger with the Spanish throne, to declare himself Emperor of Mexico.

Further south, the picture is no better for Ferdinand.

There the uprisings against Spanish rule are led by Simon Bolivar, who descends from a long line of Basque aristocrats in Spain, grows up in Caracas, Venezuela, masters warfare at the military academy there, and goes on to assume command of a series of armies which, in 1820, proclaim a new nation called Gran Colombia.

This nation, which will endure for a decade under Bolivar’s rule, extends from what is today Panama, south through the top quarter of South America, including Ecuador, northern Peru, Colombia, Venezuela and northwest Brazil.

By 1820, the Spanish hold over Paraguay, Chile and Argentina has also collapsed.

King Ferdinand VII hopes to reverse these losses and restore his rule across South America, perhaps with military help from other European monarchists bent on destroying secular governments wherever they are found, including the United States.

Ferdinand uses the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819 to try to leverage Monroe into tacitly supporting his vision.

This diplomatic quid pro quo appalls many American politicians – most notably Henry Clay – who accuses Monroe of siding with an absolutist king over oppressed people seeking freedom and self-rule. Clay’s speeches to this effect make him a hero throughout Latin America, and eventually force Monroe and Adams to exhibit a stronger hand with the Spanish monarch.

It is within this context that a new threat of foreign intrusion materializes — in the form of Tsar Alexander I, ruler of Russia and member of the powerful Holy Alliance with Austria and Prussia, who issues a decree that further rattles the administration.

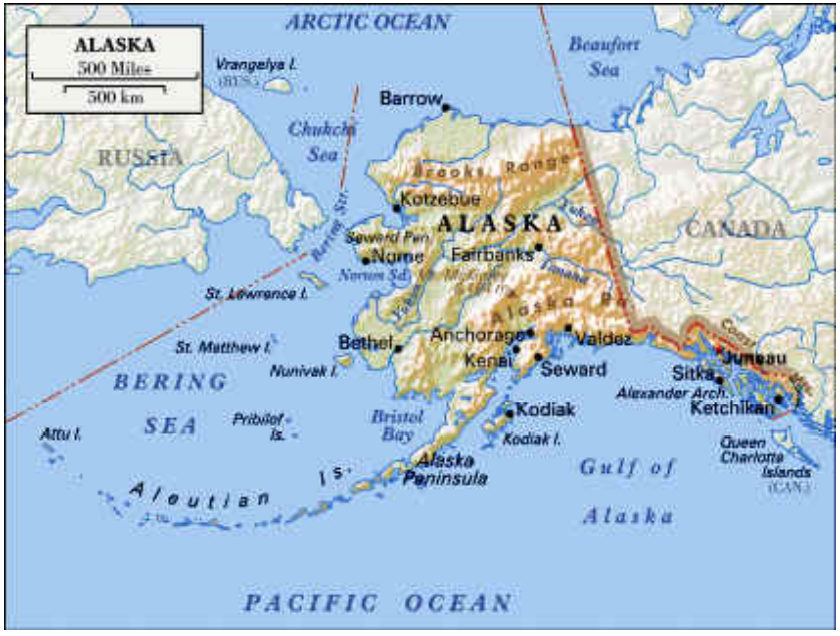

In the Ukase (decree) of 1821 the Tsar proclaims Russian sovereignty over a large swath of North America, running from Alaska in the north and west all the way down to the 45’50” parallel within the Oregon Country.

1741-1821

Russia Enters North America Through Alaska

Like Britain and America, Russia is originally drawn to the Pacific Northwest by the fur trade.

Tsarist interest here begins in Alaska, or “mainland,” in the dialect of the native Aleutian Island natives who inhabit the region.

In 1741, a Russian expedition led by the Dane, Vitus Bering, first explores Alaska. It finds a vast expanse, with latitudes ranging from 70 degrees in the north to 55 degrees in the south, and sub-freezing temperatures lasting upwards of seven months each year in the arctic zone. It also encounters almost endless herds of fur bearing mammals (seals, otters, bears, hares, fox, ermine) there for the taking.

Russian trappers follow on, with settlements springing up mainly along the southern coast. In 1784 one Grigory Shelikhov and 200 settlers found the Three Saints Bay colony on Kodiak Island. In 1799 Tsar Paul I issues a Ukase, claiming ownership of land south to the 55th parallel, and chartering Russia’s first joint-stock corporation, The Russian-American Company. It will be led by Aleksandr Baranov, a crafty fur trader and businessman, from 1799 to 1818. He drives along the southern coast, wins a major victory over the native Aluets tribes at the Battle of Sitka in 1804, and begins a push down into the Oregon Country.

Baranov establishes Russian settlements almost to San Francisco after finding that Spain has failed to occupy land in northern California. His operation there is anchored at Fort Ross, a name whose roots tie to the word Russia in his native tongue. The fort thrives from 1812 onward, with inhabitants including Russians and other Slavic people, along with native Aluet Indians.

At this point, however, Russia is operating well south of its recognized territory in Alaska – and intruding on Oregon Country land coveted not only by Spain, but also Britain and America.

Along with Ferdinand’s ambitions in Latin America, Alexander’s Ukase of 1821 serves to reignite American fears over another round of foreign invasions into the western hemisphere.

September 4, 1821

Russia Asserts A Claim To Land In The Oregon Country

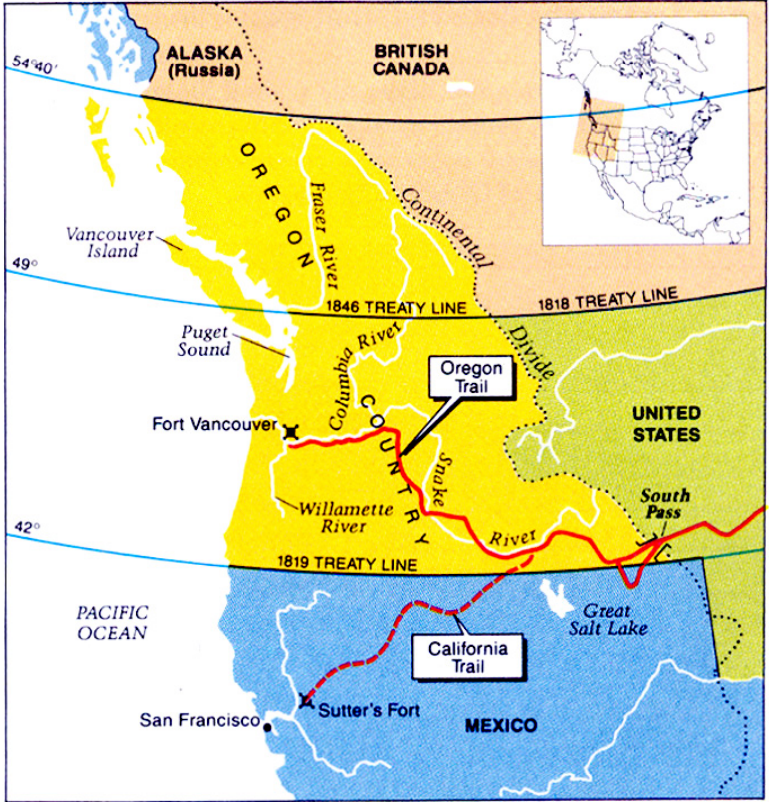

Territorial disputes to the south of Alaska over the Oregon Country are long standing.

They begin in the late 16th century when ships from both Spain and England sail along the Pacific coast.

The Spanish are first to actually claim the land, after expeditions by explorers from Juan Perez in 1774 to Bruno de Heceta and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra in 1775.

The British christen the territory “Ouragon” in 1765, and Captain James Cook makes land there in 1788 at the 43rd parallel, before proceeding north and mapping all the way over to the Bering Straits.

Then come the Americans, with Captain Robert Gray in his ship Columbia, also exploring the region in 1788. Gray is first to enter the mouth of the geographically critical 1200-mile-long river he names the Columbia in 1792. From Oregon, Gray heads west with a shipload of furs to trade in China, and becomes the first American to circumnavigate the globe. His published journals spur others to pursue trapping and trade around Oregon.

In 1792 British Captain George Vancouver sails up the Columbia River, setting the stage for operations by the Hudson Bay Company in their attempt to dominate the worldwide fur industry.

Three decades later, in 1824, Hudson will open Fort Vancouver, inland headquarters of their “Columbia District.”

The American explorers, Lewis and Clark, arrive overland in the Oregon Country in 1806. They are followed in 1811 by the tycoon, John Jacob Astor, whose American Fur Company will compete tooth and nail against Hudson Bay over the next two decades, from his post at Ft. Astoria.

Spain renounces its claims to Oregon in the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819, apparently leaving Britain and America as the only two contenders for the land rights.

But then Alexander’s Ukase of 1821 adds further complications.

After much cabinet level discussion, Monroe and Adams decide it’s time for America to resolve the borders in the Oregon Country and assert a foreign policy decree of its own.

December 2, 1823

The Monroe Doctrine Spells Out America’s Foreign Policy Across The Hemisphere

The policy decision reached is quite remarkable, and it signals the rest of the world that American democracy is now on equal footing with the monarchies of Europe and Asia.

This is Monroe at his finest, the last of the Revolutionary War presidents, determined to insure the nation’s political integrity and borders from any and all foreign threats.

Which first means the answer will be “no” to Spain’s demand to withhold recognition of the newly independent nations of Latin America, and “no” to Russia’s assertion of control over the Oregon Country.

The former comes in June of 1822, when America opens diplomatic ties with Bolivar’s Gran Columbia and in December of the same year when an independent Mexico is officially recognized.

The Russian claims are dealt with soon thereafter in what will become known as the Monroe Doctrine.

The President announces this doctrine in his annual address to Congress of December 2, 1823. The speech is lengthy, but its essence is captured in four paragraphs.

These begin with an olive branch, signaling peaceful intentions into the future, unless America’s national interests are menaced.

The citizens of the United States cherish sentiments the most friendly in favor of the liberty and happiness of their fellow men on that side of the Atlantic. In the wars of the European powers in matters relating to themselves we have never taken any part, nor does it comport with our policy so to do.

It is only when our rights are invaded or seriously menaced that we resent injuries or make preparation for our defense. With the movements in this hemisphere we are of necessity more immediately connected, and by causes which must be obvious to all enlightened and impartial observers.

Then comes an obvious, but crucial declaration – namely, that America’s “political system” is fundamentally different from the norm in the rest of the world. It stands for “enlightened citizens” choosing their own governments, and in opposition to the principle of government imposed on people by unelected dictators.

The political system of the allied powers is essentially different in this respect from that of America. This difference proceeds from that which exists in their respective Governments; and to the defense of our own, which has been achieved by the loss of so much blood and treasure, and matured by the wisdom of their most enlightened citizens, and under which we have enjoyed unexampled felicity, this whole nation is devoted.

This is followed by a policy statement informing the heads of state around the world that America will no longer tolerate new attempts at colonization anywhere in the western hemisphere.

We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere, but with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintained it, and whose independence we have, on great consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or control ling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.

This “Monroe Doctrine” will forever draw a line in the sand against any foreign power wishing to flex its military might in the Americas. It also announces to the world that the grand experiment of 1787 – a nation of free men forming their own political system – is both prosperous and viable.

It does not, however, resolve all the territorial disputes in Oregon overnight. These take time. Alexander will try to enforce his decree by seizing the American ship Pearl, but it is released with compensation paid, after a protest is made. Russia’s west coast colonies will linger until the 1840’s when they prove unprofitable. Two decades later another Tsar, Alexander II, will sell Alaska and all other North American claims to the United States, in what critics will call “(Henry) Seward’s Folly.”

Despite the delayed effects, the December 2, 1823 declaration is generally regarded as the defining moment in James Monroe’s two terms as president.