Section #8 - Efforts to end federal debt, close the U.S. Bank and restore hard currency lead to recession

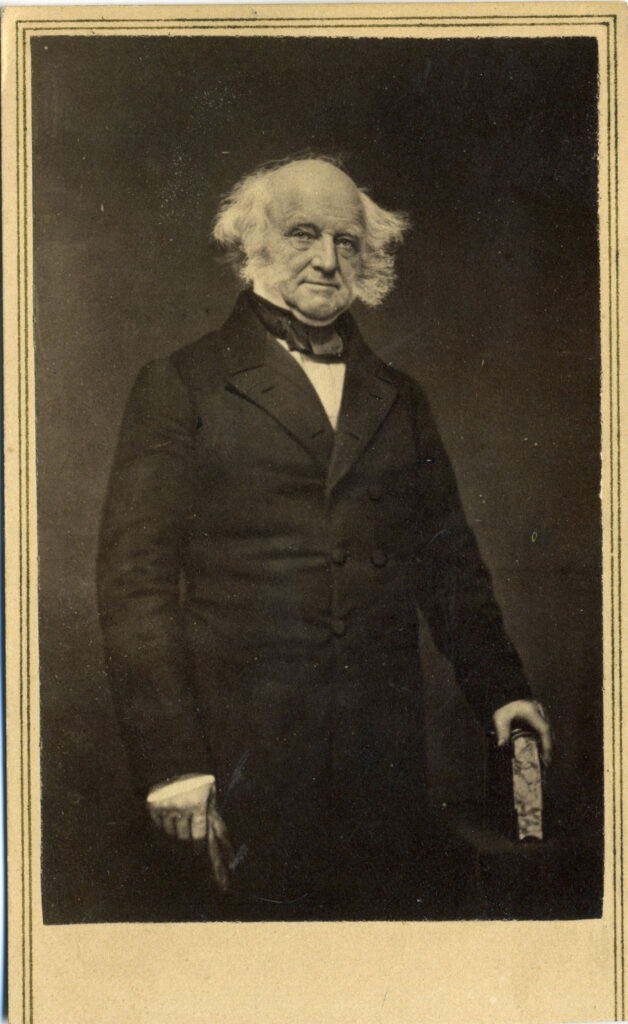

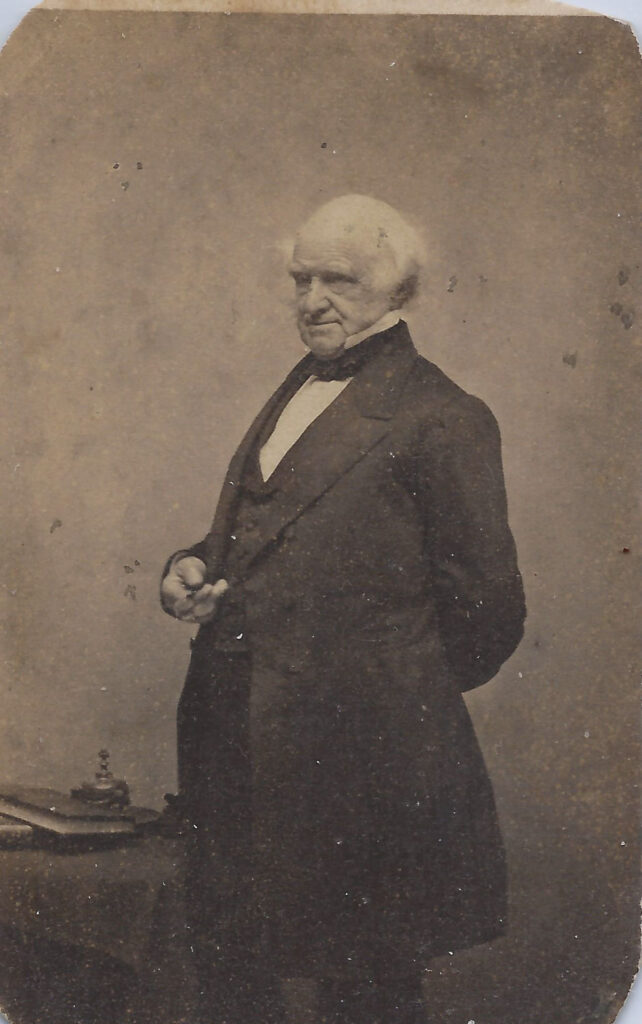

Chapter 80: Martin Van Buren’s Term

November – December 1836

The Election Of 1836

Clay’s unusual election strategy almost works, but not quite.

Ballots are cast as usual between November 3 and December 7, 1836, with the turn-out at 1.5 million voters, up from 1.3 million in 1832.

The winner turns out to be Martin Van Buren, whose margin of victory is only 51% to 49%, a sure sign that Clay’s Whig coalition is growing.

1836 Presidential Election Results

| Candidates | Party | Pop Vote | Electors | South | Border | North | West |

| Martin Van Buren | Democrat | 764,176 | 170 | 57 | 4 | 101 | 8 |

| William H. Harrison | Whig | 550,816 | 73 | 0 | 28 | 15 | 30 |

| Hugh White | Whig | 146,107 | 26 | 26 | |||

| Daniel Webster | Whig | 41,201 | 14 | 14 | |||

| Willie Mangum | Whig | — | 11 | 11 | |||

| Total | 1,502,300 294 | 94 | 32 | 130 | 38 | ||

| Needed To Win | 148 |

The Democrats carry 14 states in total, with four pick-ups from 1832 – Rhode Island, Connecticut, Michigan and Arkansas, the latter two voting for the first time.

The Whigs capture 12 states, with seven additions brought in by the regional favorites – Mangum (South Carolina), White (Georgia and Tennessee), and Harrison (Vermont, New Jersey, Ohio, and Indiana). Meanwhile, Webster keeps Massachusetts in the Anti-Jackson column.

The fact that the ex-military hero, Harrison, takes seven states overall, and dominates in the West, is not lost on Whig Party leaders looking ahead to the 1840 race.

Party Power By State

| South | 1832 | 1836 | Pick-Up | EC Votes |

| Virginia | Democrat | Democrat | 23 | |

| North Carolina | Democrat | Democrat | 15 | |

| South Carolina | Nullifier | Whig (White) | Whig | 11 |

| Georgia | Democrat | Whig (White) | Whig | 11 |

| Alabama | Democrat | Democrat | 7 | |

| Mississippi | Democrat | Democrat | 4 | |

| Louisiana | Democrat | Democrat | 5 | |

| Tennessee | Democrat | Whig (White) | Whig | 15 |

| Arkansas | — | Democrat | Democrat | 3 |

| Border | ||||

| Delaware | Nat-Rep | Whig (Har) | 3 | |

| Maryland | Nat-Rep | Whig (Har) | 10 | |

| Kentucky | Nat-Rep | Whig (Har) | 15 | |

| Missouri | Democrat | Democrat | 4 | |

| North | ||||

| New Hampshire | Democrat | Democrat | 7 | |

| Vermont | Anti-Mason | Whig (Har) | Whig | 7 |

| Massachusetts | Nat-Rep | Whig (Web) | 14 | |

| Rhode Island | Nat-Rep | Democrat | Democrat | 4 |

| Connecticut | Nat-Rep | Democrat | Democrat | 8 |

| New York | Democrat | Democrat | 42 | |

| New Jersey | Democrat | Whig (Har) | Whig | 8 |

| Pennsylvania | Democrat | Democrat | 30 | |

| Ohio | Democrat | Whig (Har) | Whig | 21 |

| Maine | Democrat | Democrat | 10 | |

| Indiana | Democrat | Whig (Har) | Whig | 9 |

| Illinois | Democrat | Democrat | 5 | |

| Michigan | — | Democrat | Democrat | 3 |

A regional analysis shows that Van Buren’s win traces to support in Northeast states with high populations and electoral vote counts – most notably New York (42) and Pennsylvania (30).

1836 Shifting State Alignments: Old/New And Slave/Free Electoral Votes

| Slavery Allowed (13) | Slavery Banned (13) | |

| Old Established East Coast States (15) | Democrats – 38 Whigs — 35 | Democrats – 101 Whigs — 29 |

| Emerging States West Of Appalachian Range (11) | Democrats – 23 Whigs — 30 | Democrats – 8 Whigs — 30 |

The four larger states west of the Appalachians go for the Whigs – Ohio (21), Kentucky (15), Tennessee (15) and Indiana (9) – while the other seven fall to the Democrats.

The thirteen “slave states” tilt by a slight 7-6 margin in favor of Van Buren.

1836 Shifting State Alignments: Old/New And Slave/Free

| Geography | Democrats | Whigs |

| Old East Coast States (15) | 8 states – 139 votes | 7 states – 64 votes |

| Emerging West States (11) | 7 states – 31 votes | 4 states – 60 votes |

| Slavery | ||

| Allowed (13) | 7 states – 61 votes | 6 states – 65 votes |

| Banned (13) | 8 states – 109 votes | 5 states – 59 votes |

The Democrats are able to retain control over both chambers of Congress in 1836 – despite losing a total of sixteen seats in the House.

Congressional Election Of 1836

| House | 1834 | 1836 | Change |

| Democrats | 143 | 127 | (16) |

| Whig | 76 | 102 | 26 |

| Anti-Masonic | 16 | 7 | (9) |

| Nullifier | 7 | 6 | (1) |

| Senate | |||

| Democrats | 26 | 35 | 9 |

| Whigs | 24 | 17 | (7) |

| Nullifier | 2 | 0 | (2) |

The election, however, holds one further surprise, when all twenty-three of Virginia’s electors refuse to cast their votes for Van Buren’s designated running mate, Richard Mentor Johnson. The Kentucky congressman has become notorious in parts of the south for declaring that Julia Chinn, an octoroon slave, is his common-law wife.

Virginia’s action leaves Johnson short of the 148 votes needed for a majority in the Electoral College, and he assumes the vice-presidency only after an affirmative vote in the Senate.

1782-1862

President Martin Van Buren: Personal Profile

Martin Van Buren is America’s first non-Anglo Saxon president, the first from New York state, and the last Northern president to have grown up in the daily presence of slaves.

He is born in 1782 in the Dutch village of Kinderhook, New York, located on the Hudson River, in an area dominated by “patroons” – powerful families, such as the Van Rensselaers and Livingstons, whose 250,000 acre estates trace to early 17th century grants. His roots are positively humbling by comparison.

His father owns a small farm along with six slaves, and runs a tavern in town. Dutch is spoken at home, and the boy learns this before mastering English. He is a precocious child, but money runs out for schooling and, at age 13 he is apprenticed to a local lawyer.

In 1801 he moves to Manhattan to continue his study, and soon comes under the magnetic influence of Aaron Burr, a mentor who will transform his destiny. Burr is already at the peak of his fame, serving as Jefferson’s Vice President after founding the Tammany Society to insure his position as godfather of New York politics. While the fatal July 1804 duel with Hamilton caps his future, Burr maintains an almost father-son relationship with Van Buren, and teaches him the merits of Jeffersonian policies along with ins and outs of organizing and aligning men with diverse interests behind a common cause.

In 1807 Van Buren returns to the Hudson Valley as a new man. He marries, begins to raise a family, and is quickly earning an astonishing $10,000 a year as a lawyer – largely by winning land disputes for small farmers against the powerful patroons who “ran such things” before he joined the scene.

The theme of his practice – the common man standing up against the power and privilege of the rich – will play out through his career and link him inexorably to both Jefferson and Jackson.

In 1812, at age 29, he enters politics as state senator by defeating the patrician Edward Livingston.

In Burr-like fashion, he organizes the “Albany Regency,” a cadre of like-minded young men who quickly dominate politics in the capital. He reaches a truce with the powerful DeWitt Clinton by backing his Erie Canal project, and in 1821 wins a close election to the U.S. Senate.

Once in Washington, Van Buren sets his sights on transforming the aging Democratic Republican apparatus into a modern political machine which he calls “The Democracy.” Rather than a loose collection of regional fiefdoms, he envisions a unified Democratic Party, holding national conventions to pick nominees and agree on a platform. Publicity for the candidates would involve a network of supportive journalists and newspapers. Those who deliver the hard detailed work during a campaign are rewarded through patronage jobs – “to the victors belong the spoils.”

From the beginning, the “sly fox” Van Buren is an excellent vote counter and political strategist. To win the White House and control the national agenda, the Democrats must:

- Lock in electoral votes across the entire South in one fell swoop – by promising never to interfere with its economically vital practice of slavery; and

- Continue to hammer home, across the North and West, the Jeffersonian virtues of a small fiscally sound federal government dedicated to advancing the interests of yeoman farmers.

Van Buren recognizes early on the shift of political power from South to North, from Virginia to New York, from slave states to free states – and identifies the associated economic fears felt across Dixie. What if a Northern dominated Washington was to suddenly turn against slavery?

The New York congressman, James Tallmadge, has already signaled this possibility in his famous anti-slavery amendment during the 1820 debate over the admission of Missouri. Southerners wonder how this threat, especially from the powerful New Yorkers, can be kept under wraps. Who better than the titular head of the Albany Regency?

Starting with his 1824 visit to Jefferson at Monticello, Van Buren tours the South on behalf of his Democratic Party vision. Ironically, he tries to nominate William Crawford rather than Andrew Jackson in the 1824 presidential race. But he recovers from this gaffe, and sets his sights on 1828, which lines up perfectly – Jackson completes a New York-Virginia-Tennessee axis for the Democrats and is up against the dour and vulnerable JQ Adams.

When Jackson wins, he brings his campaign manager into his cabinet as Secretary of State. Two years later he is in London as U.S. Ambassador, and then runs alongside Jackson as Vice President in 1832. The two men become fast friends along the way, and Van Buren is nominated unanimously at the 1835 Baltimore convention.

March 4, 1837

Van Buren Addresses Slavery In His Inaugural Speech

While Van Buren’s inaugural speech is long and tedious, it is remembered for one startling moment when he openly names and addresses the highly charged topic of “domestic slavery.”

In doing so, he acknowledges that future political debate in America will be played out within a sectional frame-work, with the South intent on protecting and expanding slavery and the North seeking to contain it.

He begins by referring to slavery as a “prominent source of discord” and one which the founders treated with “delicacy and forbearance.”

In justly balancing the powers of the Federal and State authorities, difficulties…arose at the outset, and subsequent collisions were deemed inevitable. Amid these it was scarcely believed possible that a scheme of government so complex in construction could remain uninjured.

The last, perhaps the greatest, of the prominent sources of discord and disaster supposed to lurk in our political condition was the institution of domestic slavery. Our forefathers were deeply impressed with the delicacy of this subject, and they treated it with forbearance so evidently wise that in spite of every sinister foreboding it never until the present period disturbed the tranquility of our common country.

But he now feels that the current “violence of excited passions” evident in congress – presumably the angry floor debates on abolishing slavery in the federal District of Columbia — must now be addressed.

Recent events (have) made it obvious… that the least deviation from this spirit of forbearance is injurious to every interest, that of humanity included. Amidst the violence of excited passions this generous and fraternal feeling has been sometimes disregarded; and I can not refrain from anxiously invoking my fellow-citizens never to be deaf to its dictates.

Perceiving before my election the deep interest this subject was beginning to excite, I believed it a solemn duty fully to make known my sentiments in regard to it, and now, when every motive for misrepresentation has passed away, I trust that they will be candidly weighed and understood.

At this point, Van Buren announces his stand on slavery.

He calls himself an “uncompromising opponent of every effort to abolish slavery in DC” and one who is decided to “resist the slightest interference with it in the states where it exists.”

All of this of course is music to the ears of his Southern constituency.

I must go into the Presidential chair the inflexible and uncompromising opponent of every attempt on the part of Congress to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia against the wishes of the slaveholding States, and also with a determination equally decided to resist the slightest interference with it in the States where it exists.”

The (election) result authorizes me to believe that (this view) has been approved by a majority of the people of the United States, including those whom they most immediately affect. It now only remains to add that no bill conflicting with these views can ever receive my constitutional sanction. These opinions have been adopted in the firm belief that they are in accordance with the spirit that actuated the venerated fathers of the Republic, and that succeeding experience has proved them to be humane, patriotic, expedient, honorable, and just.

From there he expresses his confidence that the recent agitation around slavery has failed to threaten “the stability our institutions” or of the Government itself.

If the agitation of this subject was intended to reach the stability of our institutions, enough has occurred to show that it has signally failed, and that in this as in every other instance the apprehensions of the timid and the hopes of the wicked for the destruction of our Government are again destined to be disappointed.

After all, he says, slavery is simply one more obstacle of many America has to overcome on the road to a prosperity secured by the Constitution.

We look back on obstacles avoided and dangers overcome, on expectations more than realized and prosperity perfectly secured.

But has prosperity been perfectly secured?

Within thirteen days of Van Buren’s optimistic address, a New York financier named Philip Hone writes, “The great (financial) crisis is near at hand, if it has not already arrived.”

Much to the new President’s chagrin, an economic depression is about to smother his high hopes for a successful administration.

March 4, 1837 – March 4, 1841

Van Buren’s Term In Office

Martin Van Buren surely lives up to his nickname as the “Little Magician” when it comes to maneuvering his way into the White House – but his stay there will prove anything but magical from start to finish.

Jackson’s “Specie Circular” order, which Van Buren supports, sets off a financial crisis that sweeps across the country and turns the population against the President and the party he has so carefully crafted. A special session of congress – the first ever assembled for a non-military threat – meets in September 1837, but fails to arrive at a solution to stabilize the currency and restore access to bank loans, the necessary fuel of capitalism. Once again the proper balance between wild speculation and prudent investment is elusive in an increasingly complex American economy.

On top of the banking woes, the public conscience is soon shocked by the murder of an abolitionist newspaperman, Elijah Lovejoy, by a white mob in Alton, Illinois, in November 1837. This event galvanizes anti-slavery advocates across the North, and, in hindsight, makes Lovejoy “the first casualty of the civil war” to follow.

Two men in particular regard Lovejoy’s murder as a call to action. One is John Brown, owner of a struggling tannery business in Ohio and future abolitionist martyr – the other is Abraham Lincoln, a 28 year old lawyer in southern Illinois, distressed by the breakdown he sees in law and order.

Lovejoy’s death, and the lack of any punishment for his killers, also prompts a renewed flood of Anti-Slavery Society petitions to congress, which JQ Adams reads in defiance of the “Gag Order” of 1836. Southern politicians rally against Adams and behind John C. Calhoun’s assertion that “slavery is a positive good” and in need of a fresh bill in congress affirming its legal legitimacy for all times.

The growing hostility on the floor turns again into open violence when the Kentucky Whig, William Graves, challenges and kills John Cilley, a Maine Democrat, in a duel over an alleged slight of honor.

To deal with the economic meltdown, Van Buren makes repeated attempts to create a new financial institution called an “Independent Treasury,” to manage federal funds and stabilize the value of the dollar. He argues that this “US Treasury” would eliminate the conflicts of interest inherent in privately held bank corporations, and would print and circulate a new supply of “properly backed” paper money to jumpstart the loan-making process. The Senate backs this initiative, but the House tables it until June 1840, fearing the move would place too much power in the hands of a President.

Conflict and frustrations bleed into Van Buren’s final years in the White House.

A Spanish slave ship, the Amistad, lands in a Connecticut port in August of 1839, filled with blacks who have killed the white crew to secure their freedom. Over the next eighteen months battles will be fought out in newspapers and in the courts about whether to return the prisoners to Spain as “slave property” or grant them liberty. Once again, JQ Adams is in the middle of the dispute, finally arguing for, and winning, their freedom before the Supreme Court.

Van Buren’s final burden centers on what to do about the Republic of Texas. Despite his fervent wish to expand to the west, Andrew Jackson has walked away from annexation in 1836 for fear of war with Mexico and the prospect of a congressional battle over admitting Texas as another slave state. But the matter doesn’t die there. The Texans again seek annexation; the South supports it; and so does Jackson, now from the safety of his retirement at the Hermitage.

Pressure mounts when both France and Britain recognize Texas as an independent nation, hardly the outcome favored by the public. Still Van Buren comes down on the side of restraint, resisting annexation for the same reasons Jackson had four years earlier.

Key Events: Martin Van Buren’s Term

| 1837 | |

| February 6 | (Pre-inauguration) Calhoun delivers his “slavery is a positive good” speech in congress |

| March 4 | Jackson and Johnson are inaugurated |

| April | Uncertainty grows about the value of the dollar and access to loans across the country |

| May 10 | Banks in New York stop redeeming dollars for gold/silver and other cities follow them |

| August 4 | Texas petitions to be annexed by the US and be admitted as a state |

| August 31 | RW Emerson’s PBK speech “The American Scholar “proclaims US intellectual honors |

| September 5 | Special Session of Congress discusses “Specie Circular” policy and bank failures |

| September 14 | Bill to create an “Independent Treasury” passes the Senate, but is tabled in the House |

| October 2 | Bank failure lead to omission of 4th installment deposits under the Surplus Revenue Act |

| October 12 | Congress authorizes printing and distribution of $10 million “backed” banknotes |

| November 7 | Abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy is murdered by an angry white mob in Alton, Illinois |

| November | John Brown “consecrates his life to ending slavery” at memorial service for Lovejoy |

| December 8 | Wendell Phillips responds to Lovejoy’s death with his first abolitionist speech |

| December 19 | “Gag Rule” renewed, with South seeking affirmation that “slavery must be protected” |

| Year | Massachusetts Board of Education head Horace Mann reforms teaching systems |

| 1838 | |

| January 10 | Calhoun speaks to the Senate about “the importance of domestic slavery” |

| January 27 | Abraham Lincoln addresses Springfield Lyceum about Lovejoy’s murder & lawlessness |

| January 3-12 | Senate affirms Calhoun resolution positively “affirming slavery as a legal institution” |

| February 15 | JQ Adams defies Gag Rule by introducing 350 anti-slavery petitions on the House floor |

| February 16 | Kentucky legislature grants suffrage to women who are widows with school age children |

| February 24 | Kentucky Whig, William Graves kills Maine Democrat, John Cilley, in a rifle duel. |

| March 26 | House opposes Van Buren’s wish to create an Independent Treasury not tied to banks |

| May 17 | White mob burns the Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia after an anti-slavery meeting |

| May 21 | Jackson’s Specie Circular Order is repealed in a joint resolution of congress |

| June 12 | The House finally passes the Independent Treasury bill by 17 votes |

| August 13 | New York banks resume payouts of dollars in gold/silver, but crisis not over |

| August 18 | Charles Wilkes sets out on expedition to explore the Pacific and Antarctic |

| October 12 | Texas withdraws annexation request and new President Lamar proposes a new nation |

| 1838 | |

| October | Remaining Cherokees removed from their eastern lands |

| November | Van Buren suffers congressional losses in the mid-term election |

| November 7 | Henry Seward is elected Governor of New York |

| December 3 | The abolitionist Joshua Giddings is elected to the House |

| Year | Underground Railroad is formed to help run-away slaves |

| 1839 | |

| February 7 | Henry Clay attacks abolitionists for risking civil war during senate debate |

| February 12 | Maine and New Brunswick dispute lumber rights along the Aroostook River |

| February 20 | Congress outlaws dueling in the District of Columbia |

| August | Slaves aboard the Amistad overthrow and kill their white crew and land on Long Island |

| September 25 | France recognizes Texas as a new nation |

| November 13 | The Liberty Party is founded by Tappan & Birney producing schism with Garrison |

| December 4 | Whig convention nominates William Henry Harrison after Clay drops out for harmony |

| 1840 | |

| January 19 | Wilkes Expedition sights Antarctica |

| March 31 | Van Buren signs bill mandating a 10 hour workday for public employees |

| April 1 | The abolitionist Liberty Party convention nominates James Birney for president |

| May 5 | Democrats nominate Van Buren on platform that supports Southern slavery |

| June 12-23 | Anti-Slavery Convention in London denies women delegates prompting backlash |

| June 30 | The House finally passes the Independent Treasury Act |

| July 4 | The Independent Treasury begins to house federal funds and stabilize the money supply |

| November 13 | Britain recognizes the nation of Texas |

| December 2 | The Whig William Henry Harrison is elected president |

| 1841 | |

| March 4 | Harrison inaugurated |

While tilted overall toward the loss column, Van Buren does record some small victories. The “Wilkes Expedition” explores and maps the Pacific Ocean and Antarctica; a border dispute between Maine and New Brunswick over lumber rights along the Aroostook River is resolved short of warfare; and “progress” continues on the transport of the eastern tribes across the Mississippi.

By 1840 per capita GDP drops sharply as a result of the financial stress caused by Jackson’s “Specie Circular” attempt to constrain land speculation and stabilize the value of the dollar. It will not be until 1847, during the Mexican War, when the broad American public enjoys another sizable jump in personal wealth.

Economic Overview: Martin Van Buren’s Presidency

| 1837 | 1838 | 1839 | 1840 | |

| Total GDP ($000) | 1554 | 1598 | 1661 | 1574 |

| % Change | 5% | 3% | 4% | (5%) |

| Per Capita GDP | 98 | 98 | 100 | 92 |

Martin Van Buren will live on for twenty-one years after exiting the Presidency, first enjoying the life of the “country squire” back in Kinderhook before returning to the political arena, hoping to regain his magical touch within the Democrat Party. But it is not to be.

He is actually favored to win the 1844 nomination, but again refuses to back the annexation of Texas. This costs him support from Southerners and Andrew Jackson, and hands the top spot to James Knox Polk.

By 1848 he feels betrayed by the Democrats and agrees to head the ticket of the new “Free Soil Party.”

During a losing campaign, Van Buren asserts that Congress has the power to limit the spread of slavery to the west – an argument that costs the Democrats a sizable number of Northern white voters, and sets the stage for the rise in 1856 of the Republican Party.

During his waning years, Van Buren does his best to support those trying to hold the Union together. He lives into the second year of the war, finally succumbing on July 24, 1862. Lincoln, who befriends Van Buren in 1842, honors his death by declaring a public day of mourning and ordering all flags to fly at half-mast.