Section #22 - The Southern States secede and the attack on Ft. Sumter signals the start of the Civil War

Chapter 283: Lincoln Sends Messengers To Charleston To Assess The Situation

March 21, 1861

Two Emissaries Head To Charleston

Lincoln is still not sure what to do next, and on March 21, 1861, he decides to gather more first-hand information about conditions in and around Ft. Sumter.

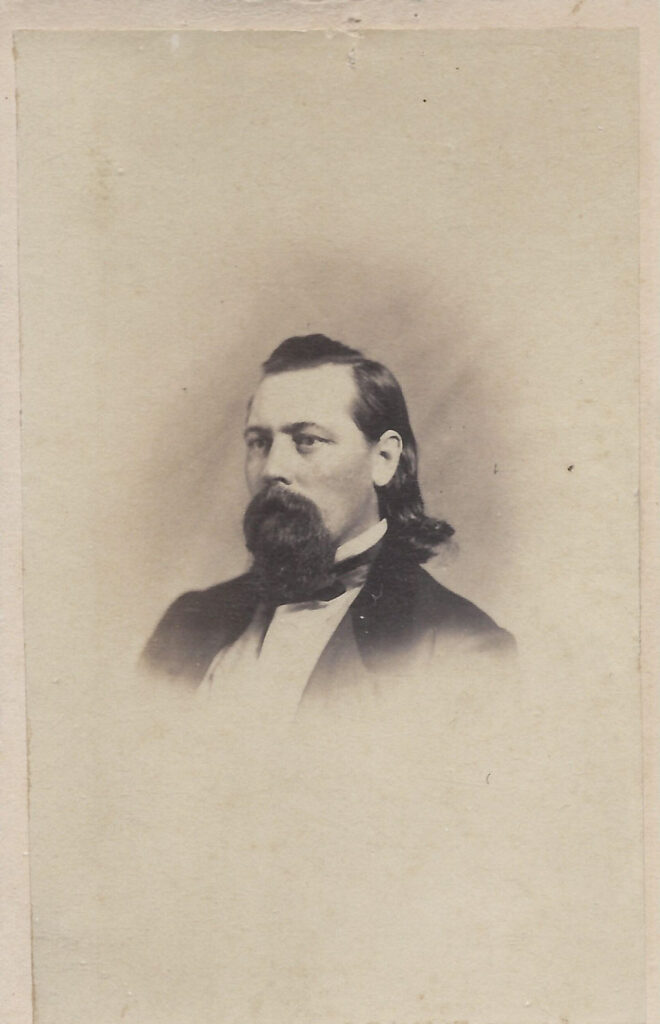

He calls for help on a long-term lawyer friend from Illinois, Stephen Hurlbut, a native of Charleston, to go there, look around, talk to the citizens and report back on his findings.

Hurlbut will be joined on the visit by the trusted bodyguard, Ward Lamon, who is tasked with reaching Governor Pickens, telling him that he is an emissary from Washington, and securing a meeting with Major Anderson to learn about conditions at the fort.

The two men depart on what will be a three day journey south.

March 23, 1861

Seward Continues To Leak The Word That Sumter Will Be Evacuated

While Lincoln seeks more information on Ft. Sumter, his Secretary of State is busily telling all comers that the fort will soon be evacuated.

He says this on March 15 to Associate Supreme Court Justice Joseph Campbell of Alabama.

He repeats it eight days later to the Russian Minister Baron de Stoeckl at a state dinner.

Word of the apparent “decision” filters south and shifts the thinking there from “if to when” regarding the turn-over of Sumter.

March 24-28, 1861

Lincoln’s Failure To Act Draws Scathing Criticism

As more days slip by without a public announcement, the pressure on Lincoln mounts from all sides, especially from Northerners siding with Seward.

Congressman Charles Francis Adams offer this criticism of the president on March 28:

The impression which I have received is that the course of the President is drifting the country into war, by want of decision. For my part I see nothing but incompetency in the head. The man is not equal to the hour.

Alarms are also heard among the party faithful:

If Ft. Sumter is evacuated, the new administration is done forever (and) the Republican Party is done.

These views are by no means unexpected or new to Lincoln.

From his one term in the House from 1847-49, up through his two losses to Stephen Douglass for a Senate seat, most Washington politicians and pundits have discounted his capacity to ever succeed in the Oval office, much less now during a national crisis.

The hope among his many critics is that the “better man,” Henry Seward, will seize the reins and act as de facto executive over the next four years.

Lincoln is well aware of the skepticism that surrounds him.

He knows that he must act soon, and he does so on the same day as Adams attacks him.