Section #19 - Regional violence ends in Kansas as a “Free State” Constitution banning all black residents passes

Chapter 230: Lincoln Begins A Senate Campaign With His “House Divided” Speech

June 16, 1858

Republicans Nominate Lincoln To Run Against Douglas In Illinois

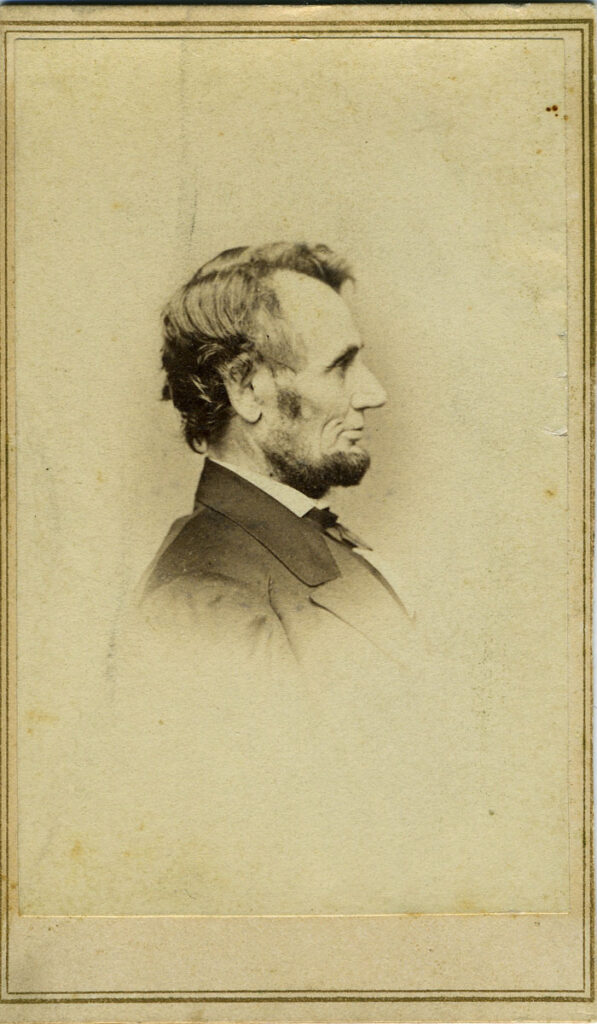

The summer of 1858 also finds a relative newcomer to the national political scene entering the debate over the crisis in Kansas. He is a 49 year old Illinois lawyer named Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln’s home base for two decades has been the town of Springfield, population 3,000, after he moves there in 1837. He fits the classical American mold of the “self-made man,” rising up from a log cabin childhood, educating himself with help from his step-mother, and earning his living in a variety of everyday jobs before deciding to read for the bar. He is soon recognized as a highly skilled advocate, “riding the circuit” on behalf of his clients, winning high profile cases, and becoming a popular figure throughout his home state. In 1842 he weds Mary Todd, a Kentucky belle, also courted by Stephen Douglas. Together they will have four sons between 1843 and 1853.

Lincoln is drawn off and on into politics, first serving three terms in the Illinois General Assembly and then in the U.S. House in 1847-49, where he is a Henry Clay-style Whig and a critic of the Mexican War. But he then backs away, returns home and concentrates on building his law firm and the wealth he seeks to support his family.

He remains on the sidelines until the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Bill and the repeal of the 1820 Missouri Compromise violate his conviction that slavery is immoral, and that it is his ethical duty to resist its spread to the west. With the backlash against the bill spreading in the North, and his Whig Party disbanded, he joins the new Republican Party.

In the Fall of 1854 he sets his sights on winning a U.S. Senate held by James Shields, a man against whom he almost fought a duel in 1842. He leads on the first six ballots cast by the state legislators, but still falls short of the needed majority. He responds by releasing his delegates to the Anti-Nebraska Democrat, Lyman Trumbull, who is elected.

Despite this defeat, the sheer clarity and power of his arguments on the slavery issue lead Republicans to nominate him in 1858 to run against Senator Stephen Douglas, who is seeking a third term.

At 8pm on June 16, 1858, Lincoln delivers his acceptance speech in front of an audience of one thousand gathered in the Springfield Hall of Representatives.

The address is titled “A House Divided Against Itself Cannot Stand,” and its main message is both controversial and captivating.

June 16, 1858

The “House Divided” Speech Begins His Campaign Against Douglas

Lincoln’s mastery as an orator is evident in the eight staccato sentences which open his acceptance address:

Mr. President and Gentlemen of the Convention — If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could then better judge what to do, and how to do it.

We are now far into the fifth year, since a policy was initiated, with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation.

Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only, not ceased, but has constantly augmented.

In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed. “A house divided against itself cannot stand.”

I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.

I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided.

It will become all one thing or all the other.

In these lines Lincoln delivers a stark message to his audience — the prolonged conflict in Kansas is symbolic of the fate that will befall America unless it can agree to either end slavery or to nationalize it.

He then argues that between the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, the Dred Scott decision and the Lecompton Constitution, the course has been set to legalize slavery in all states – even in Illinois. As he say, those who ignore this possibility…

…Shall lie down pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free; and…shall awake to the reality, instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State.

If indeed “that is whither we are tending,” what must be done to end this threat? The only answer, Lincoln says, is to prohibit the expansion of slavery into the territories by defeating those politicians who would oppose this outcome – chief among them being his opponent, Stephen Douglas.

… Clearly, he is not now with us — he does not pretend to be — he does not promise to ever be.

He ends this relatively brief address saying that if his fellow Republicans will unite behind his proposals on “what to do and how to do it,” victory will be theirs.

The result is not doubtful. We shall not fail — if we stand firm, we shall not fail. Wise councils may accelerate or mistakes delay it, but, sooner or later the victory is sure to come.

Summer 1858

Lincoln’s Speech Proves Controversial

While preparing his remarks, Lincoln asks his trusted law partner, William Herndon, about the wisdom of offering the “house divided” prediction. Herndon, a staunch anti-slavery advocate, sees some danger in the allusion:

It is true, but is it wise or politic to say so?

For many in the audience and in the national press, the response is one of alarm. Instead of reinforcing his image as a conservative Whig, the “house divided” line seems to imply that he expects, even favors, a war between the North and South to resolve the slavery dispute.

When accused of “radicalism,” Lincoln tries to deflect the criticism:

I did not say I was in favor of anything…I made a prediction only – it may have been a foolish one perhaps.

Time will tell, however, that Lincoln, the lawyer and politician, is never so inclined to loose observations.

If he is to have any chance of beating the renowned Stephen Douglas, he must first awaken the people of Illinois to the threat posed by the Democrat’s deeply flawed principle of “popular sovereignty.”

Its outcome has been five years of bloody warfare in Kansas, accompanied by violent rhetoric and threats of secession in Congress.

This pattern must end, says Lincoln, who now sets out to bring this message to the electorate.

June 26, 1858

Lincoln Begins To Shadow Douglas On The Stump

As the lesser known candidate, and a clear underdog, Lincoln decides that his only chance of winning will lie in corralling Douglas into debating him head on. To force this outcome, he begins by following Douglas to various venues around the state and offering immediate rebuttals to his speeches.

On June 26 he is in Springfield following an earlier appearance by Douglas. His remarks begin by picking away at popular sovereignty — first asking if the policy justifies the practice of polygamy in Utah, and then reminding his audience of how easily it was violated on election days in Kansas by the pro-slavery forces

He segues to Dred Scott. Unlike Douglas who supports the decision, Lincoln calls it “erroneous,” the result of a stacked Southern court, divided on the details. He insists that it is not yet “settled law” and expresses his hope to see it over-ruled.

That decision declares two propositions-first, that a negro cannot sue in the U.S. Courts; and secondly, that Congress cannot prohibit slavery in the Territories. It was made by a divided court-dividing differently on the different points… We believe, as much as Judge

Douglas, (perhaps more) in obedience to, and respect for the judicial department of government But we think the Dred Scott decision is erroneous. We know the court that made it, has often over-ruled its own decisions, and we shall do what we can to have it to over-rule this.

The notion that the founders intended to exclude negroes from having the “rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” is preposterous on the face of it.

He finds the Republicans insisting that the Declaration of Independence includes ALL men, black as well as white; and forth-with he boldly denies that it includes negroes at all,

Likewise, Douglas’ foolish assertion that Republicans wish to “marry with negroes.”

Now I protest against that counterfeit logic which concludes that, because I do not want a black woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife.

He closes here with what will become a familiar appeal to the basic goodwill and humanity of average Americans when it comes to standing against human bondage.

The Republicans inculcate, with whatever of ability they can, that the negro is a man; that his bondage is cruelly wrong, and that the field of his oppression ought not to be enlarged. The Democrats deny his manhood; deny, or dwarf to insignificance, the wrong of his bondage; so far as possible, crush all sympathy for him, and cultivate and excite hatred and disgust against him; compliment themselves as Union-savers for doing so; and call the indefinite outspreading of his bondage “a sacred right of self-government.”

July 1858

A Series Of Seven Lincoln-Douglas Debates Are Scheduled

Supporters of Douglas mock Lincoln’s follower strategy claiming that it shows his inability to attract audiences on his own. Still, he persists, and persistence finally pays off.

The two camps agree to hold a total of seven head-to-head debates, one each in the legislative districts of Illinois outside of Chicago and Springfield, where they have already been heard together.

Ground-rules for the events are worked out, along with the target dates, beginning on August 21 and continuing to October 15, 1858, only 18 days before the November 2 election.