Section #19 - Regional violence ends in Kansas as a “Free State” Constitution banning all black residents passes

Chapter 222: Kansas Voters Reject The Pro-Slavery Lecompton Constitution But Buchanan Still Tried To Save It

December 21, 1857 – January 4, 1858

A Fair Election Dooms The Pro-Slavery Cause

The time has now arrived for the people of Kansas to vote on the Lecompton Constitution.

Three such votes will be taken on the measure, the first on December 21, 1857, the other two on January 4, 1858.

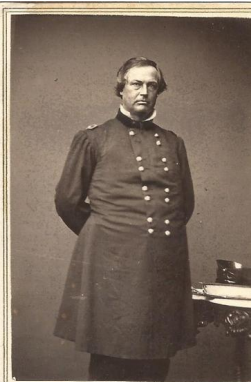

On the day of the first vote, Robert Walker’s replacement takes over as Governor. He is James Denver, a Virginian by birth, who moves to Ohio, graduates from the University of Cincinnati law school and opens a practice in Platt City, Missouri. After serving under Winfield Scott in Mexico, he settles in California, kills a man in a duel, and enters politics. He serves one term in the U.S. House before Buchanan appoints him Commissioner of Indian Affairs on April 17, 1857.

Denver knows the territory well from his prior residence in Missouri. Upon his arrival, he encourages all Kansans to turn out on December 21 to vote on the Pro-Slavers carefully contrived proposition – “to support the Constitution with Slavery or without it.”

When the Free Staters refuse to take this bait, the Pro-Slavery forces prevail again by stuffing the ballot boxes.

1st Vote On Kansas Constitution: December 21, 1857*

| With Slavery | Without Slavery | |

| Lecompton Constitution | 6,134 | 569 |

But their victory is short-lived.

Two weeks later, on January 4, 1858, a second election is held to choose the top state officers who would serve under the Lecompton Constitution.

This time the Free Staters show up at the polls in overwhelming numbers, catching the Pro Slavers off guard and leading to the president of the Lecompton Convention, John Calhoun, fleeing the state with the ballots in hand. An official election count is never issued, but Governor Denver informs Buchanan sometime in February 1858 that the Free State candidates certainly won by a large margin.

The other vote on January 4, 1858 is even more fatal to the Pro-Slavery forces and to the President.

For the first time it follows the letter of the law on popular sovereignty by placing the full Lecompton Constitution in front of the legal residents of the state. The result is an overwhelming rejection of the document and of slavery.

2nd Vote On Kansas Constitution: January 4, 1858

| Reject | Accept | |

| Lecompton Constitution In Full | 10,266 | 162 |

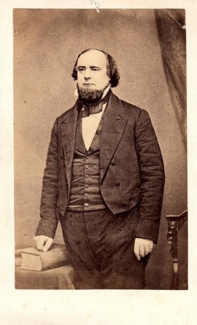

Frequent “acting governor” Frederick Stanton, dismissed along with Robert Walker, expresses his satisfaction with the outcomes.

My head will not have fallen in vain and your quondam friend, Old Buck, is welcome to all the glory he may have acquired by sacrificing me to appease the Southern nullifiers.

Meanwhile Governor Denver’s comments already mirror the frustrations of his predecessors when it comes to peacefully resolving the conflicts.

Confound the place, it seems to have been cursed of God and man. Providence gave them no crops last year, scarcely, and now it requires all he powers conferred on me by the President to prevent them from cutting each others throats.

The Free State Party has now solidified its position in Kansas. Its victory back on October 5, 1857 has given it control over the “official” legislature in the state. On January 4, 1858 it elects its own “official” ticket of state officers, and also demonstrates that the majority of Kansans reject the proposed Lecompton Constitution when a fair vote is held.

These successes convince the leaders to abandon their “separate legislative operation” in Topeka, thus depriving Buchanan of his charge that they are trying to impose a “revolutionary and illegitimate” government on the state.

In effect this sounds the death knell for the President’s pro-slavery agenda in Kansas, even though he will doggedly pursue it in Washington over the next year.

February 1858

A Stubborn Buchanan Refuses To Accept The Kansas Vote Against Slavery

As the evidence from the Kansas elections becomes clear in Washington, Northern Democrats – even in his home state of Pennsylvania — turn up the heat on Buchanan to abandon his commitment to the Lecompton Constitution.

Still the President is undeterred, and, on February 2, he asks Congress to admit Kansas under the Lecompton constitution.

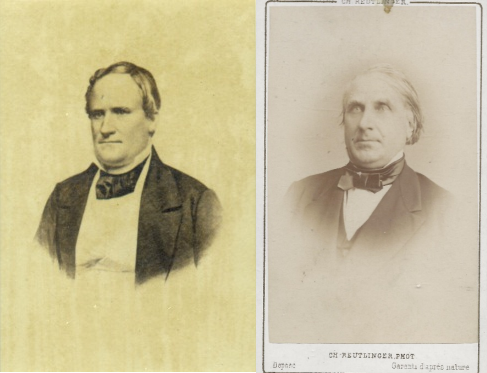

The Speaker of the House, James Orr of South Carolina, is handed the task of setting up a select committee to deliver on Buchanan’s wish. This leads to debates about which members will serve, and the extent to which they will delve into the events in Kansas that resulted in the final document.

In the evening of February 4, opponents of Lecompton attempt to sneak through a proposal to arm the committee with broad investigative powers, likely to re-visit the fraudulent elections in the Territory.

But Buchanan’s floor manager, Alexander Stephens, spots the move, and scurries around the capitol to round up enough Southerners to block it.

February 5, 1858

A Brawl Breaks Out On The Floor Of The House

The maneuvering over the shape of the committee continues past midnight with tempers fraying.

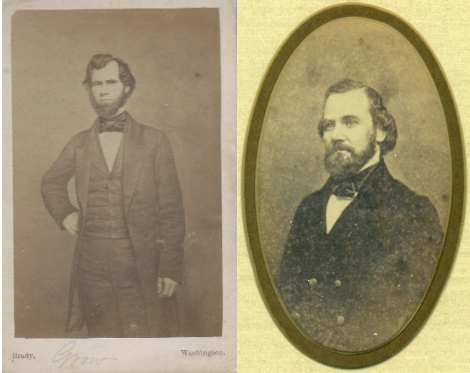

At roughly 3 am on February 5, 1858, Congressman Galusha Grow, the leader of those opposing Lecompton, crosses over from the Republican’s right side of the aisle to the left side to consult with fellow Pennsylvanian, John Hickman, a Democrat.

As he does so, the fire-eater Mississippian, John Quitman, asks to be recognized to join the debate. But Grow refuses to give up the floor.

This prompts a shout from Lawrence Keitt, a participant in the earlier caning of Charles Sumner, demanding that Grow return to his side of the chamber. When Grow brushes him off declaring “it’s a free hall,” Keitt rushes to the front of the chamber and grabs him by the throat. Their verbal exchange is recalled as follows:

Keitt to Grow: “you are a damned, black Republican puppy.”

Grow to Keitt: “no negro-driver shall crack his whip over me.”

Keitt’s assault sets off an outright brawl, while Sergeant-At-Arms, Adam Glossbrenner, waves the House Mace in a futile attempt to restore order.

Some thirty members join the melee, including Wisconsin’s John “Bowie Knife” Potter, who will earn the nickname for his weapon of choice in a threatened duel with Roger Pryor of Virginia. Potter enters the fray by landing a punch on Indiana’s John Davis with one hand, and on William Barksdale, with the other. When Barksdale responds by grabbing hold of Cadwallader Washburn, the latter’s brother, Elihu, rushes to his defense. In the process of landing a blow, he knocks the Mississippi man’s wig to the floor.

The fisticuffs continue until Barksdale put his wig back on sideways — the sight sufficiently disarming to produce a truce among the exhausted combatants.

March 5, 1858

A Stacked Sub-Committee Backs Lecompton As Is

Despite the brawl, Speaker Orr goes on to stack the committee with pro-slavery sympathizers and to constrain their scope of inquiry.

This produces the outcome he wants — a recommendation that Congress adopt the Lecompton Constitution as is, and admit Kansas as a Slave State.

The final report, delivered the first week in March, totally ignores the interference of the Border Ruffians in the process. It claims that the delegates who wrote the document were representative Kansans selected in legal fashion. It also say that the election of December 21, 1857 was legitimate and signaled support for the “Constitution With Slavery.” Beyond that, it says the Free State forces have no one but themselves to blame for the results, given their “unfortunate decisions” to boycott various events.

Then comes an attempt to deflect criticism from Northern Democrats like Douglas who say that the public was denied its right to vote on the full Lecompton Constitution –the rationale being that the full U.S. Constitution was never submitted to a popsov-like referendum.

The leading Southern politicians quickly line up behind this narrative, including Alexander Stephens, James Mason, Robert Toombs, John Slidell and Sam Houston.

Like clockwork, Governor Joseph Brown proclaims that rejection will lead him to call a convention to “determine the status of Georgia with respect to the Union.” Altogether the message is that a “no to Lecompton is a no to the entire South.”