Section #18 - After harsh political debates the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision fails to resolve slavery

Chapter 209: James Buchanan Becomes America’s Fifteenth President

Fall 1856

The Candidates Remain Aloof As The Presidential Campaigns Play Out

The events in Kansas provide a backdrop to the election campaign of 1856.

Ever since the raucous race of 1840 — with both Harrison and Van Buren “stumping” in person to the electorate –candidates have assumed the traditional posture of staying above the chase. Thereby the “dignity” of the highest office in the land is preserved by having the presidency seek the candidate and not vice versa.

Buchanan, Fremont and Fillmore all stay home and leave their fate in the hands of strategists using the available marketing tactics of the day. Some of these are straight-forward attempts to showcase key elements in the party platform, using billboards (“broadsides”) posted around towns, and lengthy editorials appearing in “party-backed” newspapers. Thus a piece in Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune will be unabashedly pro-Fremont, while John Forney’s Pennsylvanian is sure to tout James Buchanan.

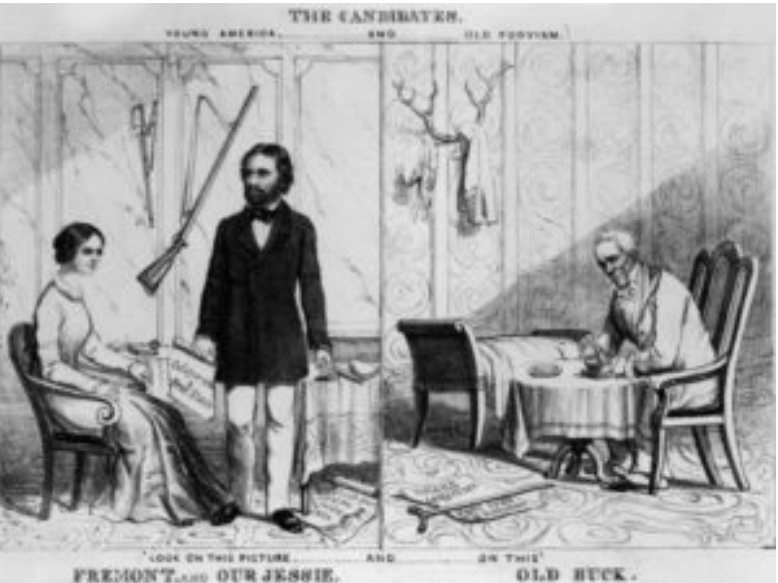

By 1856, advances in printing also facilitate the creation of elaborate woodcut political cartoons which appear in papers and weekly magazines. These typically include recognizable caricatures of the candidates along with “voice bubbles” supposedly animating their thoughts and positions on the key issues. Here, for example, is a Republican cartoon, contrasting the two leading candidates. On the left is the “manly” Fremont, youthful, bearded, standing tall in the presence of his ex-army rifle, his pathfinder maps, and his stunning wife, “Our Jesse,” daughter of a southern senator, belle of the ball. On the right is “Old Buck,” weary and slumped over in a chair, whiskerless, crutch on the floor, the aging bachelor in an effeminate dressing gown, anti-hero whose time is past.

Bottom: Fremont And Our Jesse And Old Buck

Scrolls: F (California Free State/South Pass Route) B (Ostend Manifesto/Platte Ruffians)

Further efforts to gin up enthusiasm come in the way of campaign rallies, where cider is consumed, the crowd is encouraged to physically push around a ten foot in diameter sphere made of cloth, string and tape, plastered with campaign slogans (“keep the ball rolling”), all the while chanting a range of campaign slogans and songs. For “Old Buck,” there is The White House Chair:”

Come all ye men of every state

Our creed is broad and fair

Buchanan is our candidate

We’ll put him in the White House Chair

For Fremont, a different doggerel:

A cheer for the brave Fremont

A song for the true and tried

His name is a household word

And a sound of joy and pride.

Meanwhile, behind the falderal, strategists within the three parties are deciding how best to highlight the strengths of their own tickets and tear down the competition. All sides eagerly employ scare tactics in this quest.

The Buchanan forces, known as “Buchaneers,” are particularly effective in painting Fremont as an untrustworthy option. They coin the term “Black Republican” to imply that his new party’s true agenda lies in abolition. They accuse Fremont of not only being illegitimate by birth, but also hiding his Catholicism, citing his education and that of his daughter, in Catholic schools, along with the presence of a Catholic priest at his marriage to Jesse. While Fremont is actually a committed Episcopalian, his campaign managers decide that a public denial would only extend the controversy – a decision that backfires and costs him sizable support among the nativist voters.

But perhaps the Democrat’s most compelling argument lies in warning that a Republican victory will cause the South to secede and put an end to the sacred Union.

The response from Fremont’s side is that continued appeasement of the South is undermining the most precious values that formed the Union in the first place – support for the common man over the aristocracy, free labor over slave labor, majority rule over nullification, and good over evil. The chaos in Kansas and the caning of Sumner reflect the price being paid for capitulating to the Slave Power. For the benefit of the entire nation, this must end, with the South being brought into line by a forceful president and a new Republican Party.

Instead of reigning in the South, Buchanan will continue to tilt the country toward its selfish minority demands in order to achieve his personal political goals. So they say.

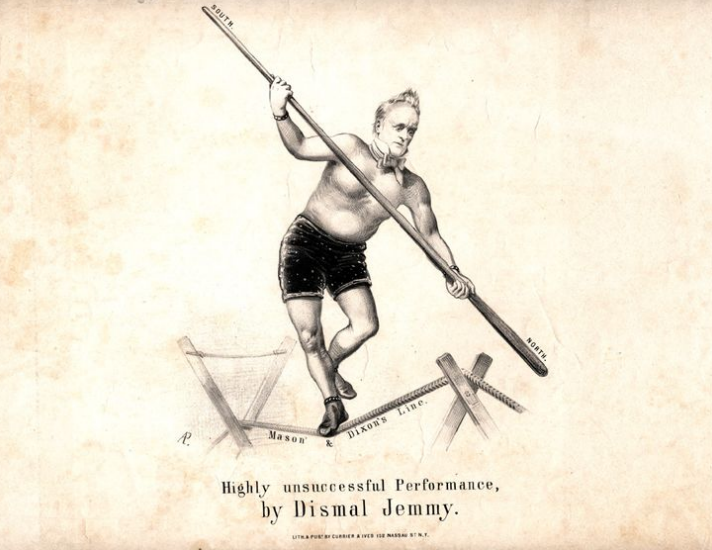

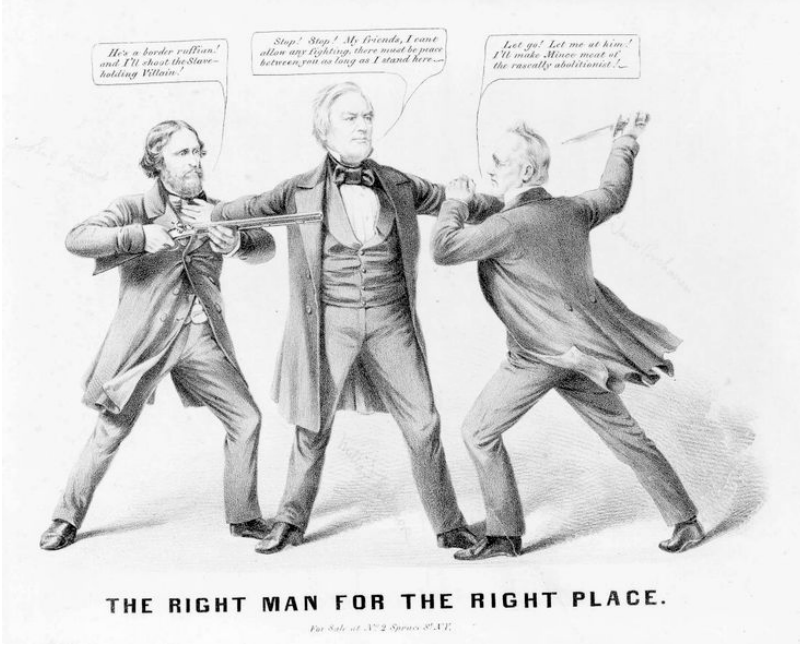

A separate and nagging problem for the Republicans is the third party presence of the “Hold-out Whigs” – with Fillmore positioning himself as the one candidate who can avoid warfare between “the abolitionist” Fremont and the “border ruffian” Fillmore. To fend off Fillmore, the Republicans remind northerners of his support for the highly unpopular 1850 Fugitive Slave Act.

Buchanan on the right: “Let me at him. I’ll make mincemeat of the rascally abolitionist.”

Fillmore in between: “Stop! My friends I can’t allow any fighting. There must be peace between you as long as I stand here.”

As Fall plays out, the race between Buchanan and Fremont is close, and public interest remains high, especially in toss-up states like Pennsylvania, with its 27 electoral votes. From the beginning, Edwin Morgan, Thurlow Weed and other Republican leaders worry about Fremont’s chances there. Not only is it Buchanan’s home state, but their own local party leaders – David Wilmot, Thad Stevens, and Simon Cameron – are all outspoken and seldom well aligned.

In the end, the Republicans will suffer from the lack of time and resources they have to create state and local party organizations that match the well-entrenched Democrats. As one campaigner aptly puts it:

In 1856 we were sort of a mob, unorganized and contending with a well-drilled and bold enemy.

November 4, 1856

The South Hands Buchanan The Victory Long Sought

When time comes for the states to print official election ballots in 1856, the South is so dead set against Fremont and the Republicans that their names do not even appear – an outcome that will also be repeated in the 1860 race.

Despite this, voter turnout jumps up to 79% in 1856, in response to intensified public interest in the shocking events in Kansas, and the emergence of a Republican Party flatly opposed to allowing Southern slavery to expand in the western territories.

Percent Of Eligibles Voting For President

| 1840 | 1844 | 1848 | 1852 | 1856 | |

| Turn-out | 80% | 79 | 73 | 70 | 79 |

The outcome, however, is almost exactly as predicted in advance by the political insider Thurlow Weed, who had persuaded Henry Seward to stay out of the race this time around. He argues that a Republican cannot win in 1856, given the Electoral College math associated with a three man race and the Democrat’s dominance in the South. Their analysis holds up on November 4, 1856, as Buchanan captures a total of 174 electoral votes, enough to become the nation’s fifteen president.

Results Of The 1856 Presidential Election

| 1856 | Party | Pop Vote | Electoral | South | Border | North | West |

| Buchanan | Democrat | 1,836,072 | 174 | 88 | 24 | 34 | 28 |

| Fremont | Republican | 1,342,345 | 114 | 0 | 0 | 76 | 38 |

| Fillmore | KN/Whig | 873,053 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 4,051,420 296 | 88 | 32 | 110 | 66 |

While Buchanan wins, his victory is anything but a mandate to govern. Unlike his predecessor, Franklin Pierce, who takes the popular vote 51%-49%, Buchanan is able to capture only 45% of all ballots cast.

Popular Votes: 1852 vs. 1856

| Election of 1852 | Democrat | Opponents | Margin |

| Total Votes | 1,607,510 | 1,554,320 | 53,190 |

| % of Total | 51% | 49% | +2 pts |

| Election of 1856 | |||

| Total Votes | 1,836,072 | 2,215,348 | (379,276) |

| % of Total | 45% | 55% | (10 pts) |

Likewise, his lead in the Electoral College pales relative to the sweep enjoyed by the Democrats in 1852.

Electoral Votes Won: 1852 vs. 1856

| Election of: | Democrat | Opponents | Margin |

| 1852 | 254 | 42 | +212 |

| 1856 | 174 | 122 | + 52 |

State by state and sectional outcomes show that the “doughface” Buchanan is indeed the darling of the pro-slavery South, where he amasses 112 of his total 174 Electoral Votes.

He surpasses the 149 needed to win by adding another 27 in his home state of Pennsylvania and 13 from Indiana, both by under 1% margins. He carries three other states by pluralities –New Jersey, Illinois, and California – when Fremont and Fillmore split the opposition ballots.

What disappears between 1852 and 1856 for the Democrats is their standing in the North and the West. Pierce previously carried 92 of 110 Electoral votes in the North and all 66 votes in the West. Buchanan is able to win only 34 in the North and 28 in the West.

The Republican Fremont takes 33% of the popular votes, capturing eight Northern states by a majority and three more by plurality. Although Fillmore wins only one state, Maryland, he makes a credible showing nationwide, with just under 22% of all ballots cast.

Two messages from the election are crystal clear. For the Democrats, their Kansas-Nebraska Bill, which opens the potential for the spread of slavery, has proven very unpopular across the North and the West. For the Republicans, they must find ways to attract Fillmore’s voters – conservative Whigs and Nativists – if they are to win in 1860.

State By State Results In The Presidential Election Of 1856

| Buchanan By Majority | Electoral | Buchanan | Fremont | Fillmore |

| South Carolina | 8 | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| Arkansas | 4 | 67 | 0 | 33 |

| Texas | 4 | 67 | 0 | 33 |

| Alabama | 9 | 63 | 0 | 37 |

| Virginia | 15 | 60 | 0 | 40 |

| Mississippi | 7 | 59 | 0 | 41 |

| Florida | 3 | 57 | 0 | 43 |

| Georgia | 10 | 57 | 0 | 43 |

| North Carolina | 10 | 57 | 0 | 43 |

| Delaware | 3 | 55 | 2 | 43 |

| Missouri | 9 | 54 | 0 | 46 |

| Kentucky | 12 | 52 | 0 | 48 |

| Louisiana | 6 | 52 | 0 | 48 |

| Tennessee | 12 | 52 | 0 | 48 |

| Indiana | 13 | 50 | 40 | 10 |

| Pennsylvania | 27 | 50 | 32 | 18 |

| Total | 152 | |||

| Buchanan By Plurality | ||||

| California | 4 | 48 | 19 | 33 |

| New Jersey | 7 | 47 | 29 | 24 |

| Illinois | 11 | 44 | 40 | 16 |

| Total | 22 | |||

| Fremont By Plurality | ||||

| Iowa | 4 | 41 | 49 | 10 |

| Ohio | 23 | 44 | 49 | 7 |

| New York | 35 | 33 | 46 | 21 |

| Total | 62 | |||

| Fremont By Majority | ||||

| Vermont | 5 | 21 | 78 | 1 |

| Massachusetts | 13 | 23 | 64 | 13 |

| Maine | 8 | 36 | 61 | 3 |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 34 | 58 | 8 |

| Michigan | 6 | 42 | 57 | 1 |

| Wisconsin | 5 | 44 | 56 | 0 |

| New Hampshire | 5 | 46 | 54 | 0 |

| Connecticut | 6 | 44 | 53 | 3 |

| Total | 52 | |||

| Fillmore By Majority | ||||

| Maryland | 8 | 45 | 0 | 55 |

| Total | 8 | |||

| Grand Total | 296 | 174 | 114 | 8 |

| Needed To Win | 149 |

The Democrats Hang On To The Majority In Congress

The 1856 congressional elections are basically good news for the Democrats. In the Senate, they maintain a large majority, albeit with a loss to three seats.

Results Of 1856 Elections: The Senate

| Party | # Seats | Gain/Loss |

| Democrats | 34 | –3 |

| Republicans | 15 | +7 |

| Whigs | 3 | –5 |

| Know Nothings | 2 | +1 |

| Total | 54 |

In the House, they restore the sizable margin that shrunk so sharply in 1854, with the momentary rise of the Know Nothing movement. With the Whigs also vanishing, their main opponents are the new Republican Party, which garners 90 seats, up from its zero total in the prior race.

Results Of 1856 Elections: The House

| Party | # Seats | Gain/Loss |

| Democrats | 133 | +52 |

| Republicans | 90 | +90 |

| Whigs | 0 | –54 |

| Know Nothings | 14 | –37 |

| Other | 0 | –24 |

| Total | 237 |

Despite the Democrat’s win, the state by state results in the House tell the same cautionary tale evident in Buchanan’s victory – namely their growing electoral dependence on dominating the slave states. Thus they win 75 of the 89 seats in the South, but only 57 of the 144 in the North.

In turn, this means that the Republicans appear now to be the favored party in the North, outpacing the Democrats there by a margin of by 87 to 57.

Both realities will have significant bearing on political decisions lying ahead relative to events in “Bloody Kansas.”

House Seats Won In The 1856 Election

| Southeast | Tot Seats | Democrats | Republicans | Know Nothing |

| Virginia | 13 (+1) | 0 (-1) | ||

| North Carolina | 7 (+2) | 1 (-2) | ||

| Georgia | 6 | 2 | ||

| South Carolina | 6 | |||

| Total | 32 | 3 | ||

| Border | ||||

| Kentucky | 8 (+4) | 2 (-4) | ||

| Maryland | 3 (+1) | 3 (-1) | ||

| Missouri | 5 (+4) | 0 (-6) | 2 (+2) | |

| Delaware | 1 (+1) | 0 (-1) | ||

| Total | 17 | 7 | ||

| Southwest | ||||

| Tennessee | 7 (+2) | 3 (-2) | ||

| Alabama | 7 (+2) | 0 (-2) | ||

| Mississippi | 5 (+1) | 0 (-1) | ||

| Louisiana | 3 | 1 | ||

| Arkansas | 2 | |||

| Texas | 2 (+1) | 0 (-1) | ||

| Florida | 1 | |||

| Total | 27 | 4 | ||

| Total South | 76 | 14 | ||

| Northeast | ||||

| New York | 12 (+7) | 21 (-4) | 0 (-3) | |

| Pennsylvania | 15 (+9) | 10 (-8) | 0 (-1) | |

| Massachusetts | 11 (+11) | 0 (-11) | ||

| Maine | 0 (-1) | 6 (+1) | ||

| New Jersey | 3 (+2) | 2 (-2) | ||

| Connecticut | 2 (+2) | 2 (+2) | 0 (-4) | |

| New Hampshire | 3 (+3) | 0 (-3) | ||

| Rhode Island | 2 (+2) | 0 (-2) | ||

| Vermont | 3 | |||

| Total | 32 | 60 | ||

| Northwest | ||||

| Ohio | 9 (+9) | 12 (-9) | ||

| Indiana | 6 (+4) | 5 (-4) | ||

| Illinois | 5 | 4 | ||

| Michigan | 0 (-1) | 4 (+1) | ||

| Total | 20 | 25 | ||

| Far West | ||||

| Wisconsin | 0 (-1) | 3 (+1) | ||

| California | 2 | |||

| Iowa | 0 (-1) | 2 (+1) | ||

| Minnesota | 2 (+2) | |||

| Oregon | 1 (+1) | |||

| Total | 5 | 5 | ||

| Total North | 57 | 90 | ||

| Total U.S. | 237 | 133 | 90 | 14 |

The choice for Speaker of the House for this 35th Congress is James Orr of South Carolina, an advocate for slavery and states’ rights, but also a Union-first man.

The minority leader in the lower chamber is Galusha Grow, a Republican from Pennsylvania.