Section #8 - Efforts to end federal debt, close the U.S. Bank and restore hard currency lead to recession

Chapter 69: Jackson “Kills” The Second Bank And Pays Off The Federal Debt

September 23, 1833

Jackson Cripples The Second Bank By Withdrawing Federal Funds

With the “Nullification Crisis” in check, Jackson returns to unfinished financial business from his first term.

Like Jefferson, he is every inch a fiscal conservative — opposed to the burdens and compromises of debt; troubled by “soft money” with its potential for speculation, inflation and unstable dollar values;” and forever suspicious of the Second Bank of the United States.

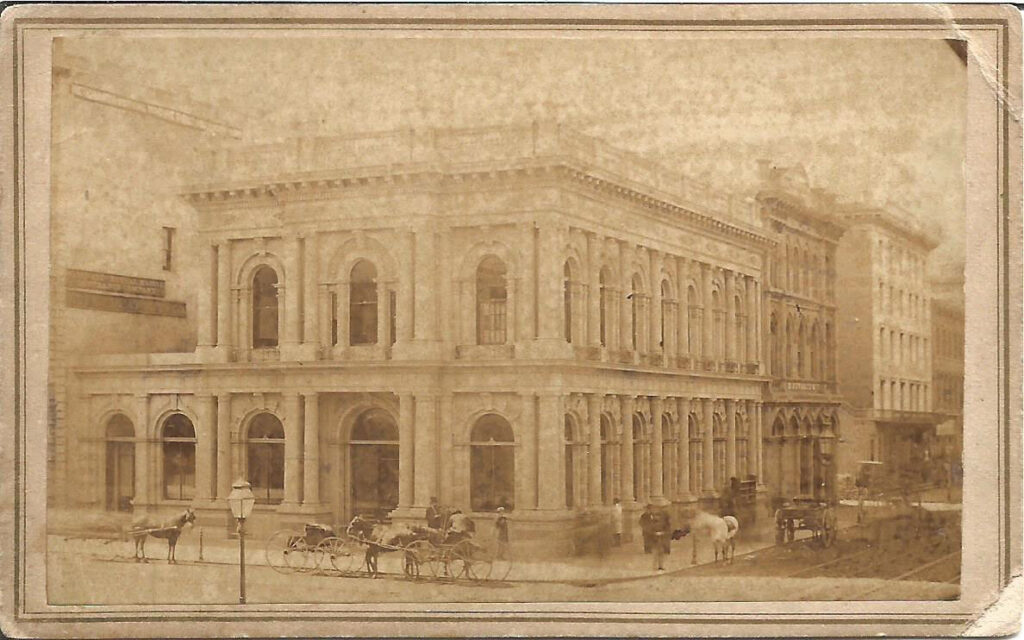

The Second Bank is established on April 10, 1816 by then President James Madison. It is a private corporation, with 20% of its stock owned by the federal government and the rest largely held by a small group of very wealthy investors. The banks charter calls for it to deposit all funds collected by the federal government and to pay all of its outstanding bills. In addition, it is charged with “regulating the value of dollars in circulation across the US.”

This regulatory duty is supposed to be accomplished by making loans of federal money to cash strapped state banks — who can prove they have the proper amount of gold/silver in their vaults to deserve the loans.

Unfortunately the Second Bank, under its initial president, William Jones, proves to be a miserable failure when it comes to protecting the dollar. In pursuit of profits for its own private investors, it prints and loans out a flood of banknotes not properly backed by gold/silver — to support the forecasted boom cycle following the end of the Napoleonic War. When the boom fails to materialize, the regulatory failures of the Second Bank lead on to the financial panic of 1819.

By 1823, savvy Second Bank investors like John Jacob Astor and Stephen Girard, convince Monroe to put Nicholas Biddle in charge, and a major turn-around in operations and results materializes by the time Jackson is first elected. Biddle makes many attempts to convince the President to look favorably upon the revitalized bank.

But Jackson will have none of this.

He is convinced that the bankers use the “monopoly status granted by the public” to enrich themselves and, possibly, even “foreign interests.” Also that this great wealth in the hands of a very wealthy few will translate into the power to corrupt the democratic process – in effect, to buy congressmen and votes. And, given the Second Bank’s roots in the East, he is forever certain that it operates on behalf of New England over the southern and western states.

He repeatedly refers to the Second Bank of the United States as “The Monster” and sets his sights on “killing it before it kills me.”

In his December 1829 address to congress he questions whether, in spite of the 1819 McCulloch v Maryland Supreme Court ruling, whether it is really constitutional for the federal government to charter a federal bank. As the hard-core state’s rights Virginian Senator John Taylor said a generation earlier:

If Congress could incorporate a bank, it might emancipate a slave.

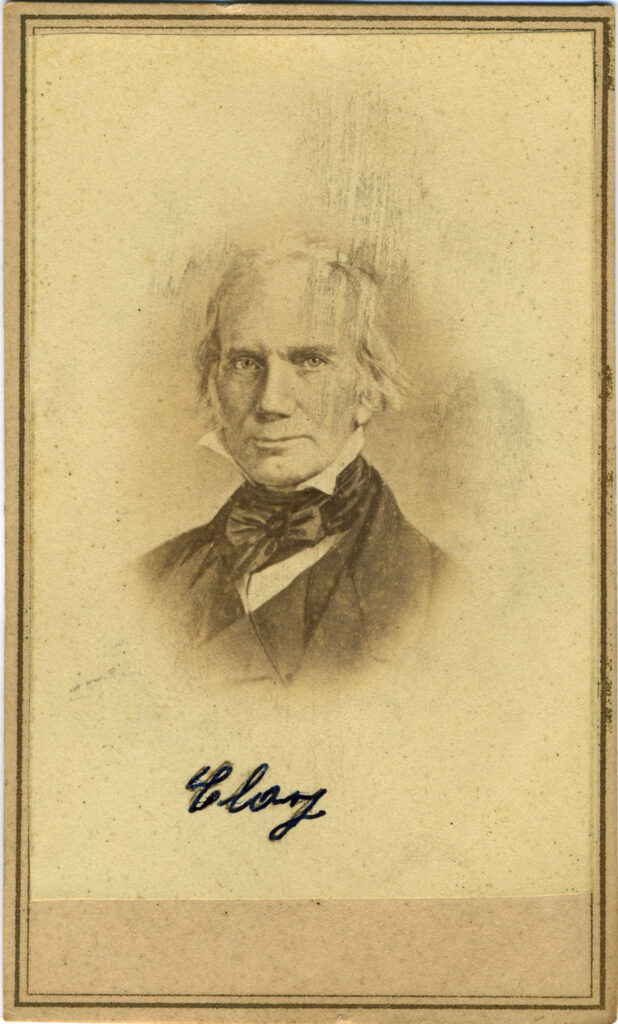

Congressional supporters of the Second Bank, notably Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, make its fate into an issue in the 1832 race for the presidency – and even pass a bill to immediately renew its corporate charter, four years before it is set to expire. Jackson vetoes this attempt, while asking contemptuously:

Is there no danger to our liberty and independence in a Bank that in its nature has so little to bind it to our country?

With the election won, closing the Second Bank almost becomes an obsession with the President.

To administer the coup de gras he decides to announce that federal funds will no longer be deposited with the Second Bank, but instead be distributed across various state banks.

He asks his own Treasury Secretary, William Duane, to make the announcement, but Duane refuses to comply.

After waiting four months, Jackson fires Duane, replaces him with Roger Taney, and issues the executive order himself, on September 23, 1833.

The order ends all prospects for a re-charter and sends Biddle on a crash mission to protect investors in the Second Bank. Cash on hand at the bank is cut in half within a few months, and to replenish the losses, Biddle “calls in” many outstanding loans, prompting a panic among borrowers, and an effective freeze on making new loans across the country.

March 28, 1834

Clay’s Censure Of Jackson Is Effectively Deflected

Jackson’s critics are apoplectic in the face of his unilateral executive action against the Second Bank.

For Henry Clay, the federal bank is a necessary element in his “American System” plan to fund infrastructure projects, especially roads and canals that cut across state lines.

He argues that, in refusing to sign the bill to re-charter the bank, Jackson has ignored the will of the people and placed the Executive branch above the Legislature.

Clay persuades the Senate on March 28, 1834 to pass a bill of censure against Jackson for “assuming upon himself authority and power not conferred by the Constitution and laws, but in derogation of both.”

But once again Jackson outmaneuvers Clay. He lobbies for support in the House, and on April 4 wins approval for all of his actions in closing the Second Bank.

After the Democrats win the 1836 election, the new congress also expunges Clay’s censure – closing the chapter on the political controversy.

“King Andrew” has successfully killed the Second Bank for good.

The United States will not see another central bank materialize until 1913, with passage of the Federal Reserve Act, in response to the panic of 1907.

1835

Jackson Pays Off The Federal Debt

With the Second Bank defeated, the ex-military General serving as President continues his assault on conquering the federal debt.

As in all things, he proves relentless – and in 1835 and 1836 he reaches his goal.

History will show that it is a record event, never to be matched again by any future President or Congress!

History Of Federal Debt

| Year | $ (000) | President |

| 1825 | 83,788 | JQ Adams |

| 1829 | 58,421 | Jackson |

| 1830 | 48,565 | Jackson |

| 1831 | 39,123 | Jackson |

| 1832 | 24,322 | Jackson |

| 1833 | 7,002 | Jackson |

| 1834 | 4,760 | Jackson |

| 1835 | 34 | Jackson |

| 1836 | 38 | Jackson |

| 1837 | 337 | Van Buren |

1790-1865

Sidebar: Long-Term Trends On The Federal Debt

Once Jackson exits, the march of the federal debt resumes – reaching heretofore unimaginable levels by the end of the Civil War, despite Abraham Lincoln’s imposition of the first personal income tax in August 1861.

| Year | $ (000) | President |

| 1825 | 83,788 | JQ Adams |

| 1829 | 58,421 | Jackson |

| 1830 | 48,565 | Jackson |

| 1831 | 39,123 | Jackson |

| 1832 | 24,322 | Jackson |

| 1833 | 7,002 | Jackson |

| 1834 | 4,760 | Jackson |

| 1835 | 34 | Jackson |

| 1836 | 38 | Jackson |

| 1837 | 337 | Van Buren |

1790-1865

Sidebar: Long-Term Trends On The Federal Debt

Once Jackson exits, the march of the federal debt resumes – reaching heretofore unimaginable levels by the end of the Civil War, despite Abraham Lincoln’s imposition of the first personal income tax in August 1861.

History Of Federal Debt

| Year | $ (000) | President |

| 1790 | $71,060 | Washington |

| 1795 | 80,748 | Washington |

| 1800 | 82,976 | Adams |

| 1805 | 82,312 | Jefferson |

| 1810 | 53,173 | Jefferson |

| 1815 | 99,834 | Madison |

| 1820 | 91,016 | Madison |

| 1825 | 83,788 | JQ Adams |

| 1830 | 48,565 | Jackson |

| 1835 | 34 | Jackson |

| 1840 | 3,573 | Van Buren |

| 1845 | 15,925 | Tyler |

| 1850 | 63,453 | Taylor |

| 1855 | 35,587 | Pierce |

| 1860 | 64,842 | Buchanan |

| 1865 | 2,680,648 | Lincoln |