Section #2 - A new Constitution is adopted and government operations start up

Interlude: The American Landscape in 1790

1790

Sidebar: “We The People Of 1790”

Our Population

Information about what life was like in the United States during its early years is more “anecdotal” than truly “fact-based.” Still the combination of data from the Census – completed once every decade beginning in 1790 – and from scholarly analysis of contemporary documents, provides a reasonable overall snapshot.

The very first U.S. Census pegs the total population in 1790 at just over 3.9 million people, including nearly 700,000 slaves.

1790 U.S. Population (000)

| Total | White | Free Blacks | Slaves |

| 3,929 | 3,174 | 57 | 698 |

| 100% | 81% | 1% | 18% |

This figure does not include a “separate nation” living west of the Appalachian mountains — the Native American tribes, whose numbers are typically estimated to be as high as two+ million.

Almost 2/3rd of all white Americans trace their roots back to the British isles, England, Scotland and Ireland – and the language of the realm is predominantly the King’s English.

1790 U.S. Population By Country Of Origin (thousands)

| Total | England | Africa | Ireland | Germany | Scotland | Neth. | A-O |

| 3,900 | 2,100 | 757 | 300 | 270 | 150 | 100 | 223 |

The total population is split about evenly between those who live North of the Mason-Dixon line (the 1767 boundary between Pennsylvania and Maryland) and those who live South of it.

1790 U.S. Population By State (thousands)

| North | Pop | South | Pop | Border | Pop |

| Penn | 434 | SC | 249 | Del | 59 |

| NJ | 184 | Ga | 82 | Md | 320 |

| Conn | 238 | Va | 748 | Ky | 74 |

| Mass | 379 | NC | 394 | ||

| NH | 142 | Tenn | 35 | ||

| NY | 340 | ||||

| RI | 69 | ||||

| Vt | 85 | ||||

| Maine | 96 | ||||

| 1,967 | 1,508 | 453 | |||

| % Total | 50% | 38% | 12% |

The median age for all Americans is very young, only 16 years, a number skewed downward by the fact that roughly 40% of children do not live into adulthood.

The average woman gives birth to 6-7 offspring – often as an economic necessity, to help work the family farm.

In the English tradition, literacy rates are high among whites in America. While public schools will not appear yet for many decades, the 1785 Northwest Ordinance already anticipates these by allocating a plot of land for education in all new township grids.

In the meantime, most children are educated at home by their parents and other family members, who are encouraged to teach reading, writing, arithmetic, common laws and religion.

Reading is deemed particularly important since it connects both adults and children to the “good book,” the Bible, which is expected to guide their behavior.

Sidebar: Our Homes

Typical American Rural Landscape: Farms and a Cemetery

In 1790, “home” for 93% of all Americans is in the countryside, on the family farm.

Where People Live In 1790

| Location | Percent |

| Rural/farms | 93% |

| Urban/cities | 7 |

Most of these farms are modest in size, with about 40% averaging 25 acres, and another 30% at 75 acres. Only 2% even approach “plantation status” at upwards of 500-1000 acres.

Typical Farm Sizes (NC)

| Acres | Percent |

| Under 10 acres | 3% |

| 10-19 | 7 |

| 20-49 | 31 |

| 50-99 | 28 |

| 100-499 | 29 |

| 500-999 | 2 |

| 1000 and over | * |

In 1790, true urban centers are few in number and all modest in size and located in major ports along the northeast coast, where they service the fishing and shipping industries.

Five Largest Cities In 1790

| Population | |

| New York | 33,131 |

| Philadelphia | 28,522 |

| Boston | 18,320 |

| Charleston | 16,345 |

| Baltimore | 13,503 |

Sidebar: Education

Given America’s roots in English traditions and culture, the value of getting an education is well established from colonial times forward.

The Puritans of New England are strong proponents of literacy, and Thomas Jefferson’s 1779 “Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge” in the Virginia Assembly touts its importance to sustaining a democracy.

Those entrusted with power have, in time, and by slow operations, perverted it into tyranny; and it is believed that the most effectual means of preventing this would be, to illuminate, as far as practicable, the minds of the people at large.

Jefferson envisions a two-tier approach to education:

One for the learned, and one for the laboring…but reading, writing and common arithmetic…should be taught to all the free children, male and female.

The capacity to read and to write will quickly become the dividing line between those with good prospects for upward social mobility and those likely to be stymied in place.

Relatively few, however, can take the process of getting an education for granted – since the task of educating children in 1790 is a family matter, not one assumed by state governments.

There are some early signs of a wish for mandatory public schools. The Massachusetts’s Law of 1647 decrees that towns with 50 families or more hire a schoolteacher, while the Land Ordinance of 1785 requires that each plat drawn for new public domain territories set aside a 640 acre parcel for a school. However, the actual implementation of state-run school programs is still more than a half century in the future.

In 1790 then, the vast majority of children experience education in a hit or miss fashion. Their teachers are typically concerned parents, most often mothers, who have received enough education themselves to pass along rudimentary skills, using popular “readers” and chalk boards. The most widely used “textbook” of the time is The New England Primer, first published around 1690. It is based on The Protestant Tutor, and is used by the Puritans to teach various scriptural lessons to children, often via rote memorization of sayings or prayers.

Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

If I should die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take.

Indeed, the motivation behind much education in the colonial is religious in character. If the path to eternal salvation lies in the Bible, one must be able to read “the good book” in order to embrace its wisdoms.

The Primer is joined in 1785 by a collection called A Grammatical Institute of the English Language. This three volume work is written and published by Noah Webster, often referred to as the “father of secular American education.” Webster graduates from Yale and takes up teaching to earn a living, an experience that leads to his lifelong interest in advancing the science of pedagogy.

The heart of Webster’s compendium is the “Blue Backed Speller,” so-called for its binding, which is used for over a century to teach children the alphabet, key words, pronunciation and reading. It is accompanied by a “reader,” intentionally non-religious, featuring historians like Plutarch to poets like Shakespeare and political essayists like Addison and Swift. Its purpose according to Webster lies in:

Diffusing the principles of virtue and patriotism.

Actual data on literacy rates in early America do not exist, so historians have tried to piece together various clues from contemporary documents. From this work, it seems likely that upwards of 90% of all men were able to sign their own names when need be. The rate for women is thought to be considerably lower, and Africans are prohibited by law from becoming educated.

The ability to read, as opposed to form letters and write one’s name, is a different matter. The two disciplines are taught separately, and reading is thought to be much less common.

By 1790, higher education is also taking hold, with most universities started by, or affiliated with, one Christian church sect or another.

America’s Earliest Colleges And Their Religious Affiliations

| Original Name | Later | Founded | Colony | Religious Link |

| New College | Harvard | 1636 | Mass | Puritan/Cong. |

| College of William & Mary | William & Mary | 1693 | Virginia | Church of England |

| King William’s School | St. Johns | 1696 | Maryland | Freemasons |

| Collegiate School | Yale | 1701 | Conn | Puritan/Cong. |

| Bethlehem Female Seminary | Moravian College | 1742 | Penn | Moravian/Hussians |

| University of Delaware | Delaware | 1743 | Delaware | Presbyterian (Old) |

| College of New Jersey | Princeton | 1746 | New Jersey | Presbyterian (Free) |

| King’s College | Columbia | 1754 | New York | Church of England |

| College of Pennsylvania | Penn | 1755 | Penn | Church of England |

| College of Rhode Island | Brown | 1764 | Rhode Island | Baptist |

| Queen’s College | Rutgers | 1766 | New Jersey | Dutch Reformed |

| Dartmouth College | Dartmouth | 1769 | NH | Congregationalist |

| College of Charleston | Charleston | 1770 | So. Carolina | Church of England |

| Salem College | Salem | 1772 | No. Carolina | Moravian/Hussites |

| Dickinson College | Dickinson | 1773 | Penn | — |

| Hampden-Sydney Academy | Hampden Sydney | 1775 | Virginia | Presbyterian |

| Transylvania University | Transylvania | 1780 | Virginia | Episcopalians |

| Washington & Jefferson | Washington & Jeff | 1781 | Penn | Presbyterian |

| University of Georgia | Georgia | 1785 | Georgia | — |

But relatively few Americans ever reach these colleges.

Those who do are typically born into the upper classes, to parents who themselves are highly educated.

These children of privilege are tutored at home or at boarding schools, where they are exposed to a classical curriculum, straight out of European academies. Around the age of sixteen they enroll at college, completing their degrees four years late, and then transition into careers ordained for their class.

At the same time, there are exceptions to the rule who tell a uniquely American narrative. These are the “self-taught” men and women who rise to fame and fortune from humble roots.

Their education is often a matter of happenstance – youthful access to a book or a teacher that sparks their curiosity, leads on to an insatiable quest for knowledge, and ends with intellectual powers and accomplishments that transport them up the social ladder.

They demonstrate the great “leveling effects” made possible in America through access to education.

Soon enough, those “to the manor born” leaders like Jefferson and Madison, will be joined center stage by “log cabin” men such as Jackson and Lincoln.

Sidebar: Making A Living

For 9 out of every 10 Americans in 1790, the path to personal prosperity centers on owning and farming one’s land.

As farmers, their existence is “pre-industrial” in character. They build and heat their own homes, from wood on their land. They grow and hunt their own food. Some even spin their own cloth, sew their own clothes, make their own shoes and candles.

In the North, the yeoman farmer raises livestock and “subsistence crops,” for his own food, and to barter for goods and services needed.

In the South, he also raises “cash crops,” such as tobacco, cotton, rice and indigo, which are sold or bartered for income and other necessities. The net value of the “average American farm” – worked without slaves – is $3,858 in the North and $2,362 in the South.

Relative Value Of Small Farms In The North Vs. The South

| Location | Own Slaves | Current Money | 2010 Equiv Money |

| North | No | $ 3,858 | $95,000 |

| South | No | 2,362 | 58,000 |

However, this relationship changes significantly for farms that utilize slave labor.

Throughout the antebellum period, roughly 1 in 3 southerners own slaves, typically five or fewer on the host of small farms, often upwards of 100 on the infrequent plantations.

On average, the net value of these southern farms with slaves is $9,634 – or about four times higher than the non-slave farms. On the mega-plantations, the relative value can be 50- fold as much.

Thus the value of owning slaves is abundantly obvious to all.

How Slaves Impacted The Value Of Small Southern Farms

| Location | Own Slaves | Value Then | Value in 2010 $ |

| South | No | $2,362 | $ 58,000 |

| South | Yes | 9,634 | 237,000 |

Regardless of geography or acreage or slaves, however,, the typical American farmer in 1790 is a rugged individualist and a hard worker, proud of whatever land he owns and of the labor he is putting in to make a living for his family.

Sidebar: The Overall U.S. Economy In 1790

While tracking economic growth in the antebellum period is more of an art form than a science, many scholars have tried to patch together data from various sources to estimate what we would now call the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP).

GDP captures the value of all newly produced goods and services in a given year. In the modern U.S. economy, about 70% of GDP traces to consumer spending, with the rest split between government services, capital purchases by corporations, and exports.

Value is typically expressed two ways: first in “current dollars” (reflecting the price of goods and services in any given year)) and second in “constant dollars” (which factors “inflation” in to show the equivalent buying power of money from one time to the next ). Thus $1 in the antebellum period is typically inflated by 20-25 times to show equivalent value in modern money.

As of 1790, experts peg America’s total GDP at about $190 million, while per capita GDP is $48 per year.

After inflation, this $190 million GDP is roughly equivalent to $4.0 Billion in “constant 2005 dollars.”

Gross Domestic Product For The U.S. In 1790

| Total GDP | Per Capita | |

| 1790 Current Dollars | $ 190MM | $ 48 |

| Constant 2005 Dollars | 4,030 | 1,025 |

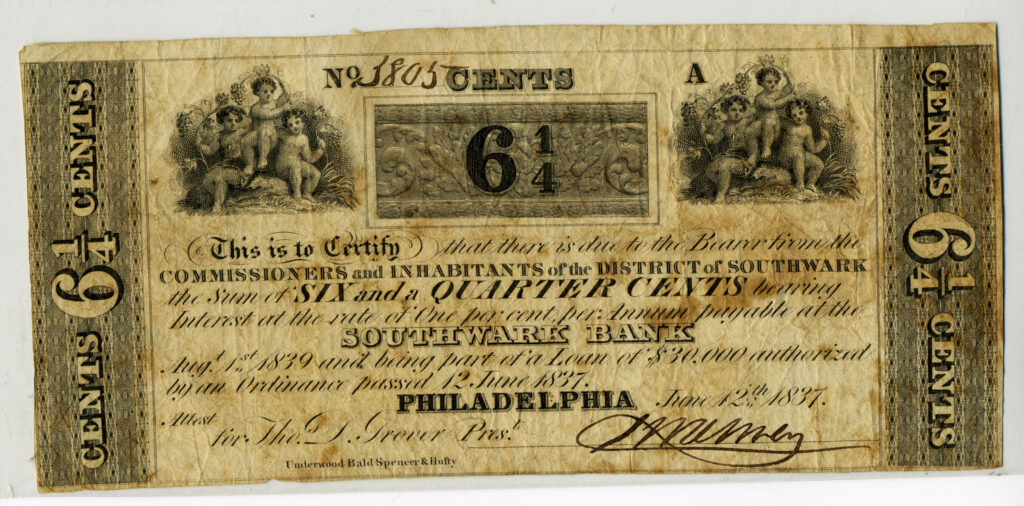

Various estimates have also been made on “annual income” for average Americans. The one measure that is trended is for “unskilled laborers,” which may be akin to today’s “minimum wage” rates. The data here show that the poorest Americans in 1790 try to scrape by on less than $1 income per week.

Annual Income – Unskilled Laborers

| Income | |

| 1790 Current Dollars | $ 37 |

This explains the “value” of the 6 ¼ cents bond shown above – one man’s attempt at beginning to save for a rainy day.

Sidebar: Commitment To The American Dream

Regardless of one’s current status in the economic hierarchy, an essential part of the American psyche is a belief in upward mobility.

The Protestant religious tradition feeds this belief in what becomes known as “The American Dream.”

According to Calvin, God hands each man a “purpose in life” and their duty is to work hard to achieve it. Those who do so, are rewarded with material wealth and success – which, in turn, are “hints” that the individual is among “the elect” chosen by God for salvation.

Herein lie the four main components behind the “American Dream:”

- Labor is an essential and dignified part of life;

- Every man has a right to the fruits of his own labor;

- Hard work pays off in increased prosperity; and

- Along with greater wealth, comes upward mobility.

Conversely, anyone or anything that erodes the American Dream hurts the nation.

This includes people who can work, but refuse to do so, along with those who live off the labor of others while “producing” nothing of value on their own.

Likewise, anyone or anything that demeans the dignity or value of labor, or stands in the way of “upward mobility” for all who work hard.

Personal success shows that a man has opted for sobriety, hard work and frugality. On the other hand, if you are lazy or a drunk or a spendthrift, then you get what you deserve.

From the beginning, commitment to the American Dream – work hard and upward mobility will follow – stands as a core belief in the national psyche.

Sidebar: Commitment To Personal Freedom

Another core value that tends to bind all Americans together in 1790 is their commitment to “personal freedom.”

Freedom to bow to no man based on heredity or rank, but rather on earned self-respect.

Freedom to form one’s own opinions and speak one’s own mind, without fear of repression.

Freedom to progress as far in life as your talent will carry you.

Freedom to experience the other unalienable rights announced in the Constitution.

Americans want nothing more than the chance to make a good life for themselves and for their families.

Playing by the rules is also an integral part of their character. They have written these rules through their own government, and woe be it to those who would skirt the law. Their instinct calls for swift and decisive justice for wrong doers.

But they also tend toward valuing community, helping each other when the need arises, and instinctively looking after those who have fallen prey to a harsh fate.

A certain idealism resides in their hidden hearts. As if the well-being of the nation rested on the moral rightness of their daily behavior.

These shared values are evident in a reprise of their home state mottoes.

- Willingness to stand tall and fight for one’s principles.

- The towering importance of personal liberty, freedom and justice vs. tyranny.

- Eagerness to seize the moment and move upward.

- Instinctive optimism and hope for future progress.

- A wish to prosper.

- A love of authenticity, plain speaking and truth-telling.

- Admiration for the virtues of preparedness, moderation, virtue and wisdom.

- The desire for peace and unity.

Mottoes For The Original 13 States

| States | Mottoes |

| Virginia | Thus Always To Tyrants |

| Massachusetts | By the sword we seek peace, but peace only under liberty. |

| New Hampshire | Live free or die |

| Delaware | Liberty and Independence |

| New York | Excelsior (Ever Upward) |

| New Jersey | Liberty and Prosperity |

| Connecticut | He who is transplanted still sustains |

| South Carolina | Prepared in mind and resources |

| Rhode Island | Hope |

| North Carolina | To be rather than to seem |

| Georgia | Wisdom, Justice and Moderation |

| Pennsylvania | Virtue, Liberty and Independence |

| Vermont | Freedom and Unity |

Sidebar: What Average White Folks Want From Their Government

In 1790 most Americans are busy working their farms, far removed from the intense philosophical debates about government that have swirled around the convention in Philadelphia.

Their political leanings, if any, probably tend to align with Jefferson:

- The paramount role for the federal government lies in dealing with foreign policy and keeping the new nation safe from external threats.

- While the role for state governments should focus on addressing any local needs or disputes that arise over time.

When the Militia Acts of 1792 are passed, most able-bodied adult men will attend militia drills in the Spring and Fall, and show up with a mandatory musket, as ordered by law.

Beyond national defense, the people’s wishes for their government are modest:

- Access to new land at affordable prices.

- An authorized surveyor to insure proper boundaries.

- A magistrate to support law and order and to collect duties.

- A rudimentary court system to adjudicate civil or criminal disputes.

- A postal service to insure certain delivery of letters.

- A state legislature to capture the will of the community on local matters.

All other matters, from educating children to building roads to overseeing most commerce, were left in the hands of the individual yeoman farmer – looking out for his own well-being.

Six Key Economic Classes In U.S. : 1790 Estimate

| Farmers | Section | Est % |

| Small northern farmers | Northeast | 45% |

| Small southern famers | Southeast | 45 |

| Plantation owners | Southeast | 1 |

| Industry | ||

| Capitalist entrepreneurs | Northeast | 1 |

| Urban wage earners | North | 5 |

| Settlers moving west | NW/SW Territories | 3 |