Section #10 - A Manifest Destiny craze results in the Texas Annexation and a victorious war with Mexico

Chapter 133: Gold Is Discovered In California

1841-1843

Johan Sutter Dreams Of A “New Switzerland” Community Along The California Trail

The U.S. conquest of the Mexican province of Alta California takes on new and dramatic importance in January 1848 with the announcement that gold has been discovered some 35 miles northeast of Sacramento, at a sawmill being constructed near Fort Sutter.

The fort is named for the German immigrant, Johann August Suter, who flees from a debt-ridden past in Switzerland in 1834 to start a new life in America. He is 31 years old at the time, and anglicizes himself as “Captain John Sutter of the Swiss Guard.” He is multi-lingual and mixes easily in the French, German and Spanish communities around St. Louis, before joining the westward tide, first to Santa Fe and then to the “Oregon Country.”

Once there, he learns the fur trapping and trading business, and decides to settle down in northern California.

Since the territory is in the hands of Mexico at the time, he goes through the laborious process of gaining permission to settle on the land, although his legal rights to the property will later be contested, much to his misfortune. In August 1840 he qualifies as a Mexican citizen and in June 1841 is given title to 49,000 acres along the American River. He christens the site “New Helvetia (Switzerland)” and dreams of establishing an old world agricultural community there, capable of thriving economically and fending off threats from both local tribes and the Mexican militia, if need be.

Between 1841 and 1843 he constructs his town center, Fort Sutter, comprising roughly six acres of land surrounded by walls that are 2.5 feet thick and stand fifteen feet high. Inside the compound is housing, a large kitchen and bakery, a smithy, carpentry shop, distillery, jail, a blanket factory, extensive storage facilities, and a supply depot and grocery store for travelers heading up or down the California Trail. Outside the compound is a flour mill, herds of cattle, and farmland, capable of providing the food and cash crops needed to sustain both settlers and guests.

The American River runs along the west side of the fort, with a dock and boats that ferry passengers some ninety miles down to San Francisco Bay.

“New Helvetia” thrives, and Sutter is soon in need of additional lumber to keep up with his plans to expand the town. To supply it, he decides to construct his own sawmill at Coloma, some 40 miles upstream from the fort. Work on the mill is contracted out to James Marshall, who comes to the fort as a carpenter in 1845, and goes on to fight alongside John C. Fremont in the 1846 “Bear Flag Revolt,” before rejoining Sutter in 1847.

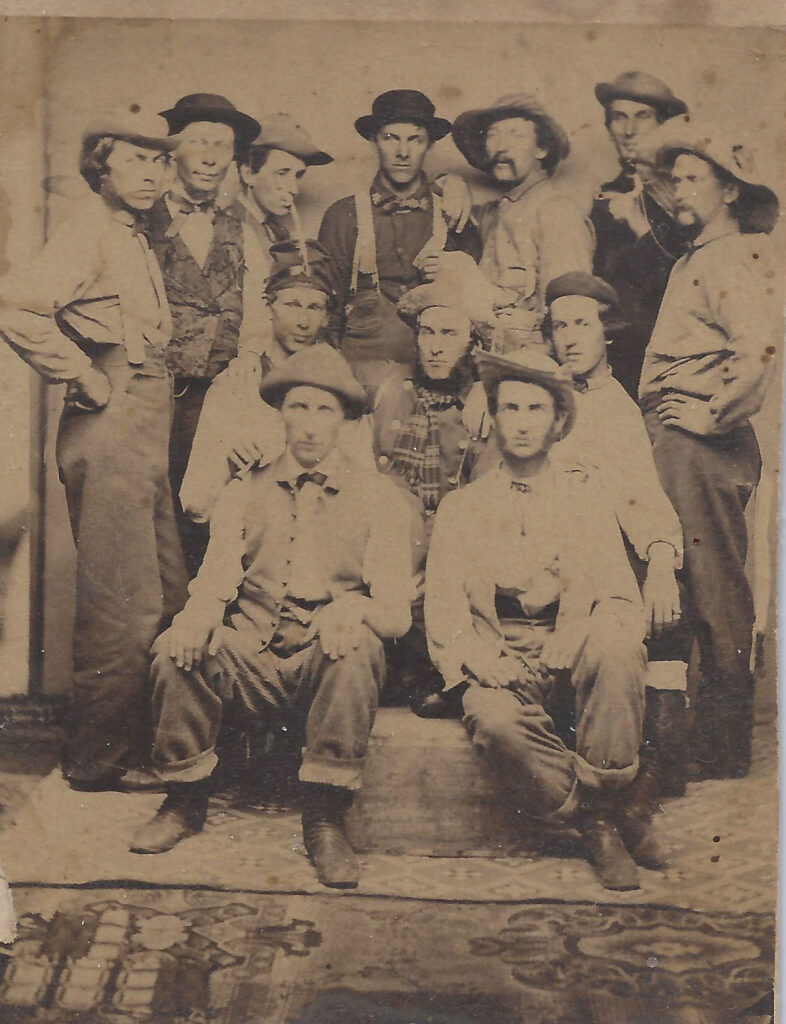

The two form a partnership, with Marshall charged with building the sawmill in exchange for wages and a share of the lumber produced. He hires a construction crew composed of local Nisenan tribesmen, and members of the “Mormon Battalion” who have stopped temporarily at the fort after the Mexican War, on their way home to Salt Lake City.

Work on the mill gets underway in August 1847.

January 24, 1848

Gold Is Discovered Nearby At Sutter’s Sawmill

Constructing a nineteenth-century water-powered sawmill is a complex endeavor, and when Marshall tries to start his up in January 1848, he immediately encounters a problem. The flow of water into and through the wheel which drives the saw blades is not fast enough to generate the rotations per minute needed. Marshall analyzes the flow and concludes that the run-off ditch (or “trace”) below the wheel must be deepened and widened. A crew begins digging to widen this trace.

On the morning of January 24, 1848, Marshall is inspecting progress on the new ditch when he spots an unusual mineral formation. One of the Mormon crew on the scene at the time, James S. Brown, later records Marshall’s words at the time:

This is a curious rock, I am afraid that it will give us trouble…I believe that it contains minerals of some kind, and I believe that there is gold in these hills…Well, we will hoist the gates and turn in all the water that we can to-night, and tomorrow morning we will shut it off and come down, and I believe we will find gold or some kind of mineral here.

The drama continues the next day, as recalled by Brown:

Marshall said, Boys, I have got her now. I, being the nearest to him, and having more curiosity than the rest of the men, jumped from the pit and stepped to him, and on looking in his hat discovered say ten or twelve pieces of small scales of what proved to be gold. I picked up the largest piece, worth about fifty cents, and tested it with my teeth, and as it did not give, I held it aloft and exclaimed, “gold, boys, gold!” At that they all dropped their tools and gathered around Mr. Marshall.

The crew on the scene agrees to keep the find a secret among themselves, while fanning out across the area around the mill for their own discoveries. Over the next few days, more nuggets materialize and the excitement builds.

Marshall decides that he must share the news with Sutter, and he sends a message back to the fort with an Indian courier. Sutter’s reactions are predictable. He first tries to contain the news locally, and then to determine whether he has any claims to the land around the mill.

Containment fails owing to a shady figure named Samuel Brannan, a Mormon and an early settler in California, who founds a newspaper in San Francisco and tries to convince Brigham Young to settle there. One of Brannan’s duties is to collect tithes for the church, and he learns of the find when several Mormons at the sawmill hand him bits of gold on his visit. His response is immediate. He buys up all of the gold mining equipment he can find – using the church tithes along with his own money – and opens a supply store near Fort Sutter – then walks the streets of San Francisco shouting out the news of “gold found along the American River!”

For his efforts, Brannan becomes one of the first gold rush millionaires, albeit after expulsion by the Mormon church for fraud.

Sutter also learns that all of the land around his sawmill is considered “in the public domain,” and is available to any miner who stakes out a claim to mineral rights on “their plot.” In response, he heads to Coloma and tries his hand at mining, but never makes a strike.

The gold rush also proves unkind to Sutter’s utopian wish for New Helvetia.

Get-rich-quick explorers from across the globe are soon squatting on his land and siphoning off his crops and livestock. His attempts to regain control are simply overwhelmed by the hoards, and his debts mount quickly. In 1849 he sells his fort for $7,000, deeds his remaining land to his son, and takes up residence in Yuba City, some fifty miles to the north. For the next thirty years, John Sutter attempts to convince the U.S. Congress to reimburse him for the loss of the land originally granted to him by Mexico, and for his important contribution to colonizing California. On June 18, 1880, his $50,000 is again ignored, and he dies two days later of heart failure at his latest residence in Lititz, Pennsylvania.

1849

The Miner 49ers Rush To California To Get Rich Quick

At first, news of the “find” at John Sutter’s sawmill on the American River is regarded with the usual skepticism by the public at large. This, despite an initial report by James Gordon Bennett’s prestigious New York Herald published on August 19, 1848.

The response changes in dramatic fashion on December 5, 1848, when President Polk confirms the discovery of quantities of the precious ore that “would scarcely command belief:”

Recent discoveries render it probable that these mines are more extensive and valuable than was anticipated. The accounts of the abundance of gold in that territory are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service who have visited the mineral district and derived the facts which they detail from personal observation.

With that, the rush is on!

The first challenge for the 49ers lies in getting to California from the east. Primary paths are identified in the press: across the Isthmus of Panama; through Nicaragua; around Cape Horn; overland along the Oregon and California Trails or various southern routes over the former or current Mexican territory. A Cape Horn ship is the safest and fastest (25-30 days) option, but the price quickly skyrockets to $400.

One adventurer who sets out in January 1849 is Samuel McNeil, a shoemaker living in Lancaster, Ohio. His journey there will cover over 3300 miles, take roughly five full months to complete, and be memorialized in his publication, McNeil’s Travels In 1849 In California.

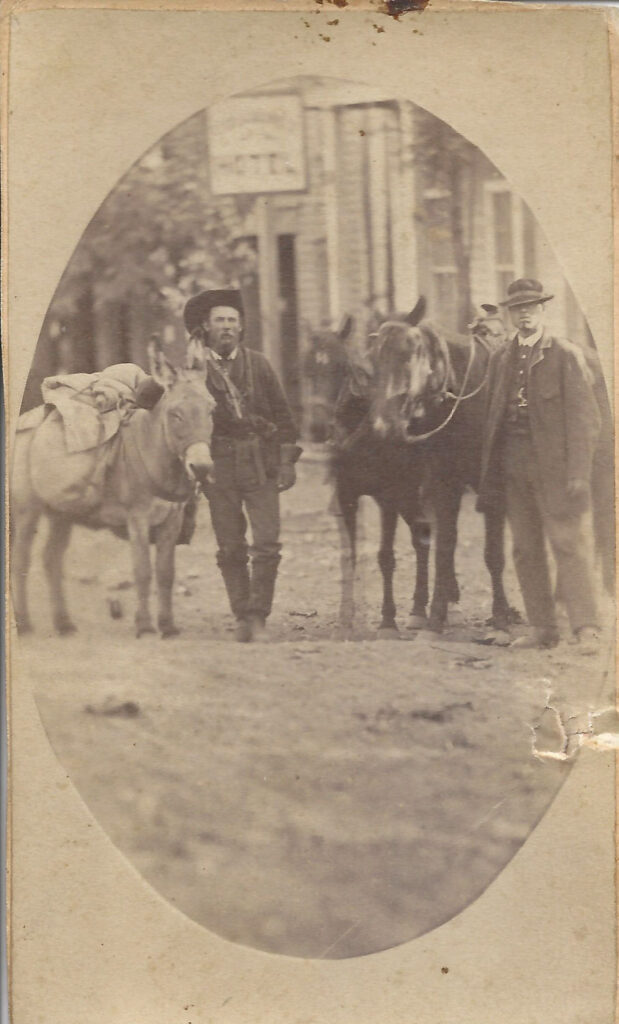

He reaches New Orleans by steamboat down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers on February 20. His intent is to continue west through Nicaragua, but instead ends up on the overland route across Mexico, first reaching the town of Brazos, where he buys a mule and rides it for over 1,000 miles to the coast at Mazatlán, arriving there on May 10. The remaining 1500 miles of his trip is completed on May 30, 1849, when the ship he is on puts in at the port of San Francisco – still, a tent city, comprising less than one thousand residents.

McNeil is finally ready to try his hand at mining for gold. He is armed with a pick and shovel, “cradle” and pan, acquired at grossly inflated prices, and whatever knowledge he has gleaned from various “how-to” write-ups that are already appearing widely in print. His destination ends up being “Smith’s Bar,” north of Sacramento, at the fork of the Bear and Feather Rivers.

Once there, McNeil makes his claim to mineral rights (but not land ownership) by putting stakes down on the plot he will be actively working day in and day out. Early on, these plots are invariably either along the banks of a river or creek or even mid-stream in the water flow. The searching Site process is done by hand, with the miner scooping shovels of black sand and gravel into either a 4-foot long “cradle” or a simple pan, and then draining off the water and shaking the container in search of flecks or nuggets of gold.

It is a back-breaking task, but made tolerable by the pay-off for success. Thus, while day laborers back east are lucky to be earning $1.00 a day in wages,

McNeil reports that the average prospector is finding $16 a day in gold, and that some fabulous finds are yielding $9,000 a week.

Such good fortune does not befall McNeil himself. He gives up after several futile weeks and decides to earn his fortune in a different fashion – by opening The Sycamore Tree Establishment,” evidently a combination saloon and brothel. While business is brisk, he is soon homesick for Ohio. On September 2, 1849 – only three months after his arrival in California – he has sold his saloon, clearing a $2,000 profit, and is back on a ship headed home to resume his former life and publish his memoirs.

As McNeil departs, other more determined 49ers are pouring into San Francisco.

By 1850 it is a full-fledged “boom town,” with 25,000 settled residents, and some 300,000 prospectors passing through over the next decade. Included here are thousands of Chinese immigrants, who are mistreated in ways generally reserved for the native tribes. Upwards of 90% of the additions are males, whose lifestyles justify the wild-wild west label they are handed.

The value of the gold they produce is staggering – reaching a high of $81 million in 1852 and then tapering off to around $45million just prior to the war. The individual prospector, panning by hand in the middle of a river, soon gives way to larger enterprises using industrialized equipment familiar with other mining operations.

Gold Produced In California

| Year | Gold Output (000) |

| 1848 | $245.3 |

| 1849 | $10,151.4 |

| 1850 | 41,273.1 |

| 1851 | 75,938.2 |

| 1852 | 81,294.7 |

| 1853 | 67,613.5 |

| 1854 | 69,433.9 |

| 1855 | 55,485.4 |

| 1856 | 57,509.4 |

| 1857 | 43,628.2 |

| 1858 | 46,095.1 |

| 1859 | 44,095.2 |

Along with the rapid growth in people and wealth comes a merchant class eager to service every wish of successful miners with gold to spend. Demand for goods and services perpetually outstrips supply, and those capable of meeting immediate needs often profit more than the average miners themselves.

Success stories abound. Two start-up bankers, Henry Wells and William Fargo, provide their customers with a safe place for their daily finds. They also open a stage-coach service which ferries travelers, along with mail, back and forth across the prairie.

One John Studebaker is making wheelbarrows just south of the gold-fields when the news breaks, and uses the profits from their sales to become a leader in manufacturing carriages. The German immigrant Levi Strauss arrives in 1850 with plans to make canvas tarps for covered wagons, then shifts to blue denim work pants quickly popularized in dry goods stores. The famous butcher and meatpacker, Philip Armour, builds his business from the $8,000 bankroll he accumulates during the rush period.

Aside from the personal fortunes created and the impact on the national economy, the gold rush of 1849 puts the issue of governance of the territory of California front and center on the agenda for the politicians in Washington.