Section #17 - The Republican Party emerges from an unlikely fusion of Free Soil and Know Nothing factions

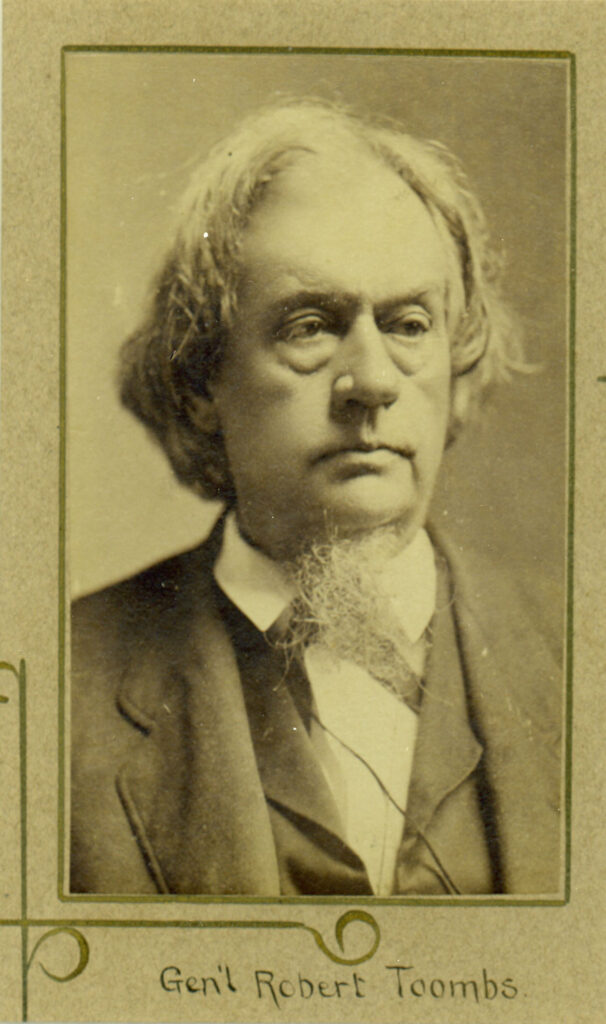

Chapter 197: Georgia’s Robert Toombs Makes The “States Rights” Case For Slavery In Boston

January 24, 1856

Toombs Is Invited To Speak In Boston About The Issue Of Slavery

Given the ongoing tension around slavery both in Boston and nationally, an invitation is sent by ex-congressman William Appleton to his former Whig colleague, Robert Toombs of Georgia, to come north to Massachusetts and provide his views on the topic. Toombs accepts and, on January 24, 1856, addresses a large gathering at the Tremont Temple, formerly a theater, now a place of worship and public lectures run by the Free Church Baptists of Boston.

Toombs is forty-five years old at the time, and has played a pivotal role all along in the North-South divisions over slavery. In 1849 he has joined Alexander Stephens, John J. Crittenden and Howell Cobb in opposing John C. Calhoun’s attempt to form a new States Rights Party to defend Southern interests.

But Toombs’s Jackson-like commitment to the sanctity of the Union is shaken by Zachary Taylor’s opposition to extending slavery into the west. In his famous January 27, 1850 speech in the House, he shocks his colleagues by asserting that he is for Disunion if the South is denied its rights in the new territories.

….I do not then hesitate to avow before this House and the country, and in the presence of the living God, that if by your legislation you seek to drive us from the Territories purchased by the common blood and treasure of the people, and to abolish slavery in the District, thereby attempting to fix a national degradation upon half the States of this confederacy, I am for Disunion,

After that threat, Toombs tries to put together a Constitutional Union Party dedicated to following the “contract” agreed to in 1787. When this fails, he becomes a Democrat in 1853, believing that it represents the best chance for the South to retain some power over its future in Washington.

In accepting Appleton’s invitation, Toombs follows Texas Senator Sam Houston who has made his case against the continuation of slavery one year earlier at the Temple. So now it is Toombs turn to offer a rebuttal, and he begins by summarizing the two points he hopes to demonstrate to the audience:

I propose to submit to you this evening some considerations and reflections upon two points.

1st. The constitutional powers and duties of the Federal Government in relation to Domestic Slavery.

2nd. The influence of Slavery as it exists in the United States upon the Slave and Society.

Under the first head I shall endeavor to show that Congress has no power to limit, restrain, or in any manner to impair slavery but, on the contrary, it is bound to protect and maintain it in the States where it exists, and wherever its flag floats and its jurisdiction is paramount.

On the second point, I maintain that so long as the African and Caucasian races co-exist in the same society, that the subordination of the African is its normal, necessary and proper condition, and that such subordination is the condition best calculated to promote the highest interest and the greatest happiness of both races, and consequently of the whole society: and that the abolition of slavery, under these conditions is not a remedy for any of the evils of the system.

January 24, 1856

Decisions About Slavery Belong With The Sovereign States Not The Federal Government

In the first part of his address, Toombs assumes the role of legal scholar lecturing his Northern audience on details of the 1787 Constitution, and agreements reached at that time on the institution of slavery.

He argues that the central debate at Philadelphia was over the proper division of power between the one aggregate Federal Government and the thirteen Sovereign States – and that this division was carefully articulated in the original document and in the Tenth Amendment within the Bill of Rights.

Simply stated, the Federal Government was assigned a set of “enumerated powers” designed to:

Make a more perfect Union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense and general welfare, and to secure the blessings of liberty to (themselves and their) posterity.

According to Toombs, these Federal powers were specified one by one in the various Articles, Sections and Clauses written, debated, resolved and ratified.

However, the founders then added the Tenth Amendment, assigning all non-enumerated powers back to each of the Sovereign States or to the people.

The powers not herein delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

This Tenth Amendment was the work of Jefferson and Madison, and it was intended to limit the power of the central government, to prohibit it from behaving like a British monarchy, and to allow local issues to be settled more effectively at the local level.

With that much stated, Toombs attempts to show how the founders applied these overarching principles to the contentious issue of slavery. He argues that the sum total of the Federal Government’s enumerated powers on slavery is contained in three sections:

The Enumerated Powers Of The Federal Government In Regard To Slavery

| Citation | Declarations |

| 1st Article, 9th Section | The importation of (slaves) shall not be prohibited by Congress prior to the year 1808 |

| 1st Article, 2nd Section, 3rd Clause | Numbers (of House seats) shall be determined by adding to the whole number of free persons…three fifths of all other persons. |

| 4th Article, 2nd Section, 3rd Clause | No person held to serve or labor in one state by the laws thereof, (and) escaping into another shall in consequence of any law therein be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due. |

Because the delegates were often deeply divided on the issue, the construction of the clauses used to clarify the intended role of the Federal Government leave no room for misinterpretation.

None of these clauses admit of misconception or doubtful construction. They were not incorporated into the charter of our liberties by surprise or inattention, they were each and all of them introduced into that body, debated, referred to committees, reported upon, and adopted. Our construction of them is supported by one unbroken and harmonious current of decisions and adjudications by the Executive, Legislature, and Judicial Departments of the Government, State and Federal, from President Washington to President Pierce.

He points out that nowhere in these enumerated powers is there any reference to the Federal Government’s authority to interfere in a state’s right to allow domestic slavery. And that precedent held firm until what Toombs regards as the “extraordinary pretension” of Federal power asserted by the “non-slaveholding states” in the 1820 Missouri Compromise legislation.

These Constitutional provisions were generally acquiesced in even by those who did not approve them, until a new and less obvious question arose out of the acquisition of territory….But in 1819, thirty years after the Constitution was adopted, upon application of Missouri into the Union the extraordinary pretension was, for the first time, asserted by a majority of the non-slaveholding States, that Congress not only had the power to prohibit the extension of slavery into new territories of the Republic, but that it had the power to compel new States seeking admission into the Union to prohibit it in their own constitutions and mould their domestic policy in all respects to suit the opinions, whims, or caprices of the Federal Government… This novel and extraordinary pretension subjected the whole power of Congress over the territories… a gigantic assumption of unlimited power in all cases whatsoever over the territories.

Those who supported the 36’30” boundary line in the 1820 Bill claimed that was required by the “necessary and proper” directive, Article 1/Section 8/Clause 18 of the Constitution:

The Congress shall have Power … To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

But, according to Toombs, the new mandate creating the 36’30” line was clearly not “necessary” given:

The fact that seven territories have been governed by Congress and trained into sovereign States without its exercise.

Nor, he says, were the “rules and regulations respecting the territories and other property of the United States” in any way “proper”…

Because they violate the fundamental condition of the Union—the equality of the States… In 1819 Florida was acquired by purchase; the laws recognized and protected slavery at the time of the acquisition. The United States extended the same recognition and protection to it. In all this legislation, embracing every act up to 1820, we find no warrant, authority, or precedent, for the prohibition of slavery by Congress in the territories.

The South was patient and acquiesced to the 36’30” boundary line, but that was no longer sufficient for the North with its “great majority” in Congress. So with the Mexican Cession land came another violation of the Constitution, denying access by Southerners from the “common territories unless they divested themselves of their slave property.”

But when we acquired California and New Mexico, the South, still willing to abide by the principle of division, again attempted to divide by the same line, it was almost unanimously resisted by the Northern States; their representatives my a great majority, insisted upon absolute prohibition and the total exclusion of the people of the Southern States from the whole of the common territories unless they divested themselves of their slave property.

He says that all the South seeks and deserves is equal treatment under the law.

We simply propose that the common territories be left open to the common enjoyment of all the people of the United States, that they shall be protected in their persons and property by the Federal Government until its authority is superseded by a State Constitution, and then we propose that the character of the domestic institutions of the new State be determined by the freemen thereof. This is justice—this is constitutional equality.

And to that end, he praises the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska for righting the 36’30” wrong and “restoring justice to the country.

The law of 1854 (commonly known as the Kansas-Nebraska act)…righted an ancient wrong, and will restore harmony because it restores justice to the country. This legislation I have endeavored to show is just, fair, and equal; that it is sustained by principle, by authority, and by the practice of our fathers. I trust, I believe, that when the transient passions of the day shall have subsided, and reason shall have resumed her dominion, it will be approved, even applauded, by the collective body of the people, in every portion of our widely extended Republic.

In this part of his Tremont Temple address, Toombs makes the strongest case possible for the “States Rights” defense on slavery. It harkens back to the 1787 Convention and the adoption of the Tenth Amendment. It says that according to the enumerated powers assigned to the Federal Government in the Constitution, Congress has no legal authority to deny Southerners the right to bring their slave property into the common territories of the west. Period.

But, having made that much clear, the Georgian continues in Boston to stand aside from the Southern “Fire-Eaters” – men like Robert Rhett, William Yancey, James Hammond, David Atchison and others – who would sacrifice the Union in order to expand slavery. Instead, if the settlers in each new state are allowed to vote on the issue in accordance with the Kansas Nebraska rules, then Toombs says he is willing to live with the results.

At this point, he shifts to the second part of his lecture – the defense of slavery itself.

January 24, 1856

Blacks Are Much Better Off As Slaves In The South Than Freedmen In The North

The second half of Toombs’s address involves a lengthy discussion of “the effect of Southern slavery on the Slaves and on Society.” His thoughts follow those laid out in the 1852 compendium The Pro-Slavery Argument, based on articles and lectures from Professor Thomas Roderick Dew, jurist William Harper, novelist Dr. George Gilmore Sims, and “fire-eater” James Henry Hammond.

Although, unlike the others, Toombs refrains from implying that the Bible itself sanctions the practice. Instead, he begins by asserting that the enslavement of blacks has been in place since time immemorial.

The monuments of the ancient Egyptians carry (the slave) back to the morning of time— older than the pyramids—they furnish the evidence, both of his national identity and his social degradation before history began. We first behold him a slave in foreign lands; we then find the great body of his race slaves in their native land; and after thirty centuries, illuminated by both ancient and modern civilization, have passed over him, we still find him a slave of savage masters, as incapable as himself of even attempting a single step in civilization.

In America, it was the British who established slavery and wove it into the colonial society, especially in the South.

I have already stated that African slavery existed in all of the colonies at the commencement of the American Revolution. The paramount authority of the Crown, with or without the consent of the colonies, had introduced it, and it was inextricably interwoven with the frame-work of society, especially in the Southern States.

The institution was then legally ordained, according to Toombs, because it was obvious that “the African race…is incapable as freemen of securing their own happiness or promoting the public prosperity.”

The slaveholding States, acting upon these principles, finding the African race among them in slavery, unfit to be trusted with political power, incapable as freemen of securing their own happiness, or promoting the public prosperity, recognized their condition as slaves, and subjected it to legal control…. They sought that system of government which would secure the greatest and most enduring happiness to the whole society.

Here is the crux of the rationalization of slavery that flows from Jefferson to Toombs’s South in the 1850’s – and also resonates among the vast majority of Northerners. It is that blacks are an inferior species – 3/5th of a full man by law — incapable of even caring for themselves, much less contributing to society. Not because they were violently yanked from their native culture and sold like livestock, witnessed their families being torn apart, were underfed and left uneducated, often suffered physical and sexual abuse, were worked to exhaustion by overseers, and were insured daily of their inferiority. No, the outcome is not about this circumstance, rather about their intrinsic “nature.”

Proof of the Africans inherent inferiority, Toombs says, lies in the lack of progress they have demonstrated when set free. He cites two examples from abroad to demonstrate that they are incapable of creating a viable society, first the sixty year old black revolution in Haiti, and then the results of the 1838 emancipation in Jamaica.

Their condition in Hayti has now been tested for sixty years, and the results are before the world…. Revolutions, tumults, and disorders have been the ordinary pastime of the emancipated blacks; industry has almost ceased, and their stock of civilization acquired in slavery has been already nearly exhausted, and they are now scarcely distinguished from the tribes from which they were torn in their native land….More recently the same experiment has been tried in Jamaica, under the auspices of England. This was one of the most beautiful, productive, and prosperous of the British colonial possessions. In 1838, England, following the false theories of her own abolitionists, proclaimed total emancipation of the black race in Jamaica.

The outcome, he argues, is the same in America, where one is able to “study the African race” living as freedmen versus slaves. According to the abolitionists, the free blacks of the North should be far advanced from the slaves of the South. And yet their plight up North is one of abject, despair.

In the United States too we have peculiar opportunities of studying the African race under different conditions. Upon the theory of the anti-slavery men, the most favorable condition in which you can view the African ought to be in the non-slaveholding States of this Union. There we ought to expect to find him displaying all the capabilities of his race for improvement and progress…(where) he has had seventy years in which to cleanse himself and his race from the leprosy of slavery. Yet what is his condition here today? He is free; he is lord of himself; but he finds it is truly a “heritage of woe.”

After this seventy years of education and probation…his inferiority stands as fully a confessed fact in the non-slaveholding as in the slaveholding States. By them he is adjudged unfit to enjoy the rights and perform the duties of citizenship—denied social equality by an irreversible law of nature, and political rights, by municipal law, incapable of maintaining the unequal struggle with the superior race; the melancholy history of his career of freedom is here most usually found in the records of criminal courts, jails, poor-houses, and penitentiaries… the negro, true to the instincts of his nature, buries himself in filth, and sloth, and crime.

These facts have had themselves recognized in the most decisive manners throughout the Northern States. No town, or city, or State, encourages their immigration; many of them discourage it by legislation; some of the non-slaveholding States have prohibited their entry into their borders by any circumstances whatever. Thus, it seems, this great fact of “inferiority” of the race is equally admitted everywhere in our country…The Northern States admit it, and to rid themselves of the burden, inflict the most cruel injuries upon an unhappy race; they expel them from their borders and drive them out of their boundaries, as wanderers and outcasts.

Toombs then makes the familiar argument that the Africans are better off as slaves in the South than freedmen in the North.

The Southern States, acting upon the same admitted facts, treat them differently. They keep them in the same subordinate position in which they found them, protect them against themselves, and compel them to contribute to their own and the public welfare; and under this system, we appeal to facts, open to all men, to prove that the African race has attained a higher degree of comfort and happiness than his race has ever before attained in any other age or country.

Our political system gives the slave great and valuable rights. His life is equally protected with that of his master: his person is secure from assault against all others except his master, and his master’s power in this respect is placed under salutary and legal restraints. He is entitled, by law, to a home, to ample food and clothing, and exempted from “excessive” labor; and, when no longer capable of labor, in old age and disease, he is a legal charge upon his master. His family, old and young, whether capable of labor or not, from the cradle to the grave, have the same legal rights; and in these legal provisions, they enjoy as large a proportion of the products of their labor as any class of unskilled hired laborers in the world.

He claims that his conclusions are based on “public statistics,” citing many examples. At the same time, he identifies criticisms levelled at the institution – dismissing some, but also displaying rare objectivity about the need to correct others. His intent throughout this section seems to be to convince his audience that any broad brush condemnation of slavery is simply inaccurate.

Our slaves are larger consumers of animal food than any population in Europe, and…their natural increase (birth rates) is equal to that of any other people; these are true and undisputable tests that their physical comforts are amply secured.

In the division of the earnings of labor between it and capital, the southern slave has a marked advantage over the English laborer, and is often equal to the free laborer of the North.

It is objected that religious instruction is denied the slave…(but) a much larger number of the race in slavery enjoy the consolation of religion…and conversion to Christianity (than) all the millions of their countrymen who remained in their native land.

The immoralities of the slaves…are lamentably great; but it remains to be shown that they are greater than with the laboring poor of England, or any other country.

It is objected that our slaves are debarred the benefit of education…(a point) well taken…Formerly in none of the slaveholding States, was it forbidden to teach slaves to read and write, but the character of the literature sought to be furnished them by the abolitionists caused these States… to lay the ax at the root of the evil; better counsels will in time prevail, and this will be remedied.

The want of legal protection to the marriage relation is also a fruitful source of agitation among the opponents of slavery…and is not without foundation. But, in truth and fact, marriage does exist in a very great extent among slaves, and is encouraged and protected by their owners…. To protect…domestic ties by laws forbidding…the separation of families, would be wise, proper, and humane, and some of the slaveholding States have already adopted partial legislation (to) remove those evils. But the injustice and despotism of England towards Ireland has produced more separation of Irish families, and sundered more domestic ties within the last ten years than African slavery has effected since its introduction into the United States.

Overall then, Toombs is convinced that the institution of slavery is proven to be a “positive good” for the blacks themselves. The question of why, if this is so, the slaves express such misery and attempt to run away, is left unasked and unanswered.

I submit that the proposition is fully proven, that the position in slavery among us is superior to any which he has ever attained in any age or country. The picture is not without shade as well as light; evils and imperfections cling to man and all of his works, and this is not exempt from them. The condition of the slave offers good opportunity for abuse, and these opportunities are frequently used to violate humanity and justice. But… the general happiness, cheerfulness, and contentment of slaves, attest both the mildness and humanity of the system and their natural adaptation to their condition.

Toombs’s speech now turns to the slave’s impact on American society as a whole?

January 24, 1856

With Its Slavery The Southern States Lead The World In Prosperity

Toombs begins here by disputing the assertions that slave labor is unproductive and that the institution has undermined the economic well-being of the Southern states.

The next aspect in which I propose to examine this question is, its effects upon the material interests of the slaveholding States. Thirty years ago slavery was assailed mainly on the ground that it was a dear, wasteful, unprofitable labor, and we were urged to emancipate the blacks, in order to make them more useful and productive members of society.

An inquiry into the wealth and production of the slaveholding States of this Union demonstrates that slave labor can be economically and profitably employed.

As proof of the productivity of slave labor, he cites the fact that Southern goods account for 3/4ths of all exports created by the entire U.S. economy. This is despite a white population that is less than one-half that of the North.

The slaveholding States with one half the white population and between three and four millions of slaves, furnish above three fourths of the annual exports of the Republic counting twenty-three millions of people; and their entire products, including every branch of industry, greatly exceed per capita those of the more populous Northern States.

The skilled application of capital and slave labor in the South yields the highest levels of productivity while insuring optimal returns for investors and much greater care for workers than seen among the North’s sweatshops.

The opponents of slavery, passing by the question of material interests, insist that its effects on the society where it exists is to demoralize and enervate it, and render it incapable of advancement and a high civilization and upon the citizen to debase him morally and intellectually. Such is not the lesson taught by history…nor the experience of the past or present.

No stronger evidence of what progress society may make with domestic slavery can be desired, than that which the present condition of the slaveholding States presents….Labor, united with capital, directed by skill, forecast and intelligence…is capable of its highest production, is freed from all these evils, leaves a margin, both for the increased comforts to the laborer, and additional profits to capital.

Furthermore, the South has achieved these results based on its own ingenuity and efforts, without any significant aid from the Federal Government.

None of this great improvement and progress have been even aided by the Federal Government; we have neither sought from it protection from our private pursuits, nor appropriations for our public improvements. They have been effected by the unaided individual efforts of an enlightened, moral, energetic, and religious people. Such is our social system, such is our condition under it. Its political wisdom is vindicated on its effect upon society; the morality by the practices of the patriarchs and the teachings of the apostles; we submit it to the judgment of mankind, with the firm conviction that the adoption of no other system under our circumstances would have exhibited the individual man, bond or free, in a higher development, or society in a higher civilization.

Rather than criticizing the South, the North should recognize and applaud the society it has built and the positive role slavery has played to the benefit of all.

In surveying the whole civilized world, the eye rests not on a single spot where all classes of society are so well content with their social system, or have greater reason to be so, than in the slaveholding States of this Union. Stability, progress, order, peace, content, prosperity, reign throughout our borders.

January 24, 1856

Toombs Stands As A Weathervane For Southern Moderates

Within four years of his Boston address, Robert Toombs will have lost faith in finding a compromise with those opposing the expansion of slavery. He will eventually resign his seat in the Senate, join the Confederacy as its first Secretary of State, and then serve in combat during the war as a Brigadier General, suffering a wound at the battle of Antietam.

But on January 24, 1856 he “explains” the Southern case regarding slavery to his Northern audience as he sees it and in crystal clear fashion.

Unlike the Fire-Eaters, he also remains willing to allow the Democrats policy of “pop sov” to decide future outcomes on a state-by-state basis.

As such, Toombs stands in Boston as a weathervane for those Southerners who still cling to hope about saving the Union.